| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XV THE PAMPA OF GHOSTS TWO days later we

left

Conservidayoc for Espiritu

Pampa by the trail which Saavedra’s son and our Pampaconas Indians had

been

clearing. We emerged from the thickets near a promontory where there

was a fine

view down the valley and particularly of a heavily wooded alluvial fan

just

below us. In it were two or three small clearings and the little oval

huts of

the savages of Espiritu Pampa, the “Pampa of Ghosts.” On top of the

promontory was

the ruin of a small,

rectangular building of rough stone, once probably an Inca watch-tower.

From

here to Espiritu Pampa our trail followed an ancient stone stairway,

about four

feet in width and nearly a third of a mile long. It was built of uncut

stones.

Possibly it was the work of those soldiers whose chief duty it was to

watch

from the top of the promontory and who used their spare time making

roads. We

arrived at the principal clearing just as a heavy thunder-shower began.

The

huts were empty. Obviously their occupants had seen us coming and had

disappeared in the jungle. We hesitated to enter the home of a savage

without

an invitation, but the terrific downpour overcame our scruples, if not

our

nervousness. The hut had a steeply pitched roof. Its sides were made of

small

logs driven endwise into the ground and fastened together with vines. A

small

fire had been burning on the ground. Near the embers were two old black

ollas

of Inca origin. In the little chacra,

cassava, coca,

and

sweet potatoes were growing in haphazard fashion among charred and

fallen tree

trunks; a typical milpa farm. In the clearing were

the ruins of eighteen

or twenty circular houses arranged in an irregular group. We wondered

if this

could be the “Inca city” which Lopez Torres had reported. Among the

ruins we

picked up several fragments of Inca pottery. There was nothing Incaic

about the

buildings. One was rectangular and one was spade-shaped, but all the

rest were

round. The buildings varied in diameter from fifteen to twenty feet.

Each had

but a single opening. The walls had tumbled down, but gave no evidence

of

careful construction. Not far away, in woods which had not yet been

cleared by

the savages, we found other circular walls. They were still standing to

a

height of about four feet. If the savages have extended their milpa

clearings

since our visit, the falling trees have probably spoiled these walls by

now.

The ancient village probably belonged to a tribe which acknowledged

allegiance

to the Incas, but the architecture of the buildings gave no indication

of their

having been constructed by the Incas themselves. We began to wonder

whether the

“Pampa of Ghosts” really had anything important in store for us.

Undoubtedly

this alluvial fan had been highly prized in this country of terribly

steep

hills. It must have been inhabited, off and on, for many centuries. Yet

this

was not an “Inca city.” While we were

wondering whether

the Incas themselves

ever lived here, there suddenly appeared the naked figure of a sturdy

young

savage, armed with a stout bow and long arrows, and wearing a fillet of

bamboo.

He had been hunting and showed us a bird he had shot. Soon afterwards

there

came the two adult savages we had met at Saavedra’s, accompanied by a

cross-eyed friend, all wearing long tunics. They offered to guide us to

other

ruins. It was very difficult for us to follow their rapid pace. Half an

hour’s

scramble through the jungle brought us to a pampa or

natural terrace on

the banks of a little tributary of the Pampaconas. They called it

Eromboni.

Here we found several old artificial terraces and the rough foundations

of a

long, rectangular building 192 feet by 24 feet. It might have had

twenty-four

doors, twelve in front and twelve in back, each three and a half feet

wide. No

lintels were in evidence. The walls were only a foot high. There was

very

little building material in sight. Apparently the structure had never

been

completed. Near by was a typical Inca fountain with three stone spouts,

or conduits.

Two hundred yards beyond the water-carrier’s rendezvous, hidden behind

a

curtain of hanging vines and thickets so dense we could not see more

than a few

feet in any direction, the savages showed us the ruins of a group of

stone

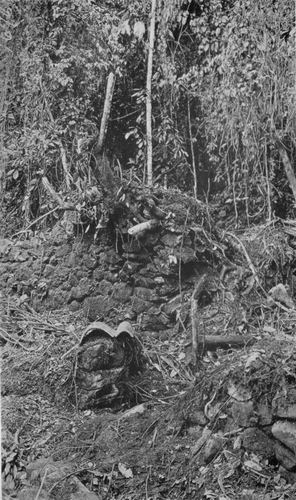

houses whose walls were still standing in fine condition.  INCA RUINS IN THE JUNGLES OF ESPIRITU PAMPAS One of the buildings

was

rounded at one end.

Another, standing by itself at the south end of a little pampa,

had

neither doors nor windows. It was rectangular. Its four or five niches

were

arranged with unique irregularity. Furthermore, they were two feet

deep, an

unusual dimension. Probably this was a storehouse. On the cast side of

the

pampa was a structure, 120 feet long by 21 feet wide, divided

into five

rooms of unequal size. The walls were of rough stones laid in adobe.

Like some

of the Inca buildings at Ollantaytambo, the lintels of the doors were

made of

three or four narrow uncut ashlars. Some rooms had niches. On the north

side of

the pampa was another rectangular building. On the

west side was the

edge of a stone-faced terrace. Below it was a partly enclosed fountain

or

bathhouse, with a stone spout and a stone-lined basin. The shapes of

the

houses, their general arrangement, the niches, stone roof-pegs and

lintels, all

point to Inca builders. In the buildings we picked up several fragments

of Inca

pottery. Equally interesting

and very

puzzling were half a

dozen crude Spanish roofing tiles, baked red. All the pieces and

fragments we

could find would not have covered four square feet. They were of widely

different sizes, as though some one had been experimenting. Perhaps an

Inca who

had seen the new red tiled roofs of Cuzco had tried to reproduce them

here in

the jungle, but without success. At dusk we all

returned to

Espiritu Pampa. Our

faces, hands, and clothes had been torn by the jungle; our feet were

weary and

sore. Nevertheless the day’s work had been very satisfactory and we

prepared to

enjoy a good night’s rest. Alas, we were doomed to disappointment.

During the

day someone had brought to the hut eight tame but noisy macaws.

Furthermore,

our savage helpers determined to make the night hideous with cries,

tom-toms,

and drums, either to discourage the visits of hostile Indians or

jaguars, or

for the purpose of exorcising the demons brought by the white men, or

else to

cheer up their families, who were undoubtedly hiding in the jungle near

by. The next day the

savages and

our carriers continued

to clear away as much as possible of the tangled growth near the best

ruins. In

this process, to the intense surprise not only of ourselves, but also

of the

savages, they discovered, just below the “bathhouse” where we had stood

the day

before, the well-preserved ruins of two buildings of superior

construction,

well fitted with stone-pegs and numerous niches, very symmetrically

arranged.

These houses stood by themselves on a little artificial terrace.

Fragments of

characteristic Inca pottery were found on the floor, including pieces

of a

large aryballus. Nothing gives a

better idea of

the density of the

jungle than the fact that the savages themselves had often been within

five

feet of these fine walls without being aware of their existence. Encouraged by this

important

discovery of the most

characteristic Inca ruins found in the valley, we continued the search,

but all

that any one was able to find was a carefully built stone bridge over a

brook.

Saavedra’s son questioned the savages carefully. They said they knew of

no

other antiquities. Who built the stone buildings of Espiritu Pampa and

Eromboni

Pampa? Was this the “Vilcabamba Viejo” of Father Calancha, that

“University of

Idolatry where lived the teachers who were wizards and masters of

abomination,”

the place to which Friar Marcos and Friar Diego went with so much

suffering?

Was there formerly on this trail a place called Ungacacha where the

monks had

to wade, and amused Titu Cusi by the way they handled their monastic

robes in

the water? They called it a “three days’ journey over rough country.”

Another

reference in Father Calancha speaks of Puquiura as being “two long

days’

journey from Vilcabamba.” It took us five days to go from Espiritu

Pampa to

Pucyura, although Indians, unencumbered by burdens, and spurred on by

necessity, might do it in three. It is possible to fit some other

details of

the story into this locality, although there is no place on the road

called

Ungacacha. Nevertheless it does not seem to me reasonable to suppose

that the

priests and Virgins of the Sun (the personnel of the “University of

Idolatry”)

who fled from cold Cuzco with Manco and were established by him

somewhere in

the fastnesses of Uilcapampa would have cared to live in the hot valley

of

Espiritu Pampa. The difference in climate is as great as that between

Scotland

and Egypt, or New York and Havana. They would not have found in

Espiritu Pampa

the food which they liked. Furthermore, they could have found the

seclusion and

safety which they craved just as well in several other parts of the

province,

particularly at Machu Picchu, together with a cool, bracing climate and

food-stuffs more nearly resembling those to which they were accustomed.

Finally

Calancha says “Vilcabamba the Old” was “the largest city” in the

province, a

term far more applicable to Machu Picchu or even to Choqquequirau than

to

Espiritu Pampa. On the other hand

there seems

to be no doubt that

Espiritu Pampa in the montaņa does

meet the requirements of the place called Vilcabamba by the companions

of

Captain Garcia. They speak of it as the town and valley to which Tupac

Amaru,

the last Inca, escaped after his forces lost the “young fortress” of

Uiticos.

Ocampo, doubtless wishing to emphasize the difference between it and

his own

metropolis, the Spanish town of Vilcabamba, calls the refuge of Tupac

“Vilcabamba the old.” Ocampo’s new “Vilcabamba” was not in existence

when Friar

Marcos and Friar Diego lived in this province. If Calancha wrote his

chronicles

from their notes, the term “old” would not apply to Espiritu Pampa, but

to an

older Vilcabamba than either of the places known to Ocampo. The ruins are of late

Inca

pattern, not of a kind

which would have required a long period to build. The unfinished

building may

have been under construction during the latter part of the reign of

Titu Cusi.

It was Titu Cusi’s desire that Rodriguez de Figueroa should meet him at

Pampaconas. The Inca evidently came from a Vilcabamba down in the montãna, and, as has been said, brought

Rodriguez a present of a macaw and two hampers of peanuts, articles of

trade

still common at Conservidayoc. There appears to me every reason to

believe that

the ruins of Espiritu Pampa are those of one of the favorite residences

of this

Inca — the very Vilcabamba, in fact, where he spent his boyhood and

from which

he journeyed to meet Rodriguez in 1565.1 In 1572, when Captain

Garcia

took up the pursuit of

Tupac Amaru after the victory of Vilcabamba, the Inca fled “inland

toward the

valley of Simaponte ... to the country of the Manaries Indians, a

warlike tribe

and his friends, where balsas and canoes were

posted to save him and

enable him to escape.” There is now no valley in this vicinity called

Simaponte, so far as we have been able to discover. The Manaries

Indians are

said to have lived on the banks of the lower Urubamba. In order to

reach their

country Tupac Amaru probably went down the Pampaconas from Espiritu

Pampa. From

the “Pampa of Ghosts” to canoe navigation would have been but a short

journey.

Evidently his friends who helped him to escape were canoemen. Captain

Garcia

gives an account of the pursuit of Tupac Amaru in which he says that,

not

deterred by the dangers of the jungle or the river, he constructed five

rafts

on which he put some of his soldiers and, accompanying them himself,

went down

the rapids, escaping death many times by swimming, until he arrived at

a place

called Momori, only to find that the Inca, learning of his approach,

had gone

farther into the woods. Nothing daunted, Garcia followed him, although

he and

his men now had to go on foot and barefooted, with hardly anything to

eat, most

of their provisions having been lost in the river, until they finally

caught

Tupac and his friends; a tragic ending to a terrible chase, hard on the

white

man and fatal for the Incas. It was with great

regret that I

was now unable to

follow the Pampaconas River to its junction with the Urubamba. It

seemed

possible that the Pampaconas might be known as the Sirialo, or the

Coribeni,

both of which were believed by Dr. Bowman’s canoe-men to rise in the

mountains

of Vilcabamba. It was not, however, until the summer of 1915 that we

were able

definitely to learn that the Pampaconas was really a branch of the

Cosireni. It

seems likely that the Cosireni was once called the “Simaponte.” Whether

the

Comberciato is the “ Momori” is hard to say. To be the next to

follow in the

footsteps of Tupac

Amaru and Captain Garcia was the privilege of Messrs. Heller, Ford, and

Maynard. They found that the unpleasant features had not been

exaggerated. They

were tormented by insects and great quantities of ants — a small red

ant found

on tree trunks, and a large black one, about an inch in length,

frequently seen

among the leaves on the ground. The bite of the red ant caused a

stinging and

burning for about fifteen minutes. One of their carriers who was bitten

in the

foot by a black ant suffered intense pain for a number of hours. Not

only his foot,

but also his leg and hip were affected. The savages were both fishermen

and

hunters; the fish being taken with nets, the game killed with bows and

arrows.

Peccaries were shot from a blind made of palm leaves a few feet from a

runway.

Fishing brought rather meager results. Three Indians fished all night

and

caught only one fish, a perch weighing about four pounds. The temperature was

so high

that candles could

easily be tied in knots. Excessive humidity caused all leather articles

to

become blue with mould. Clouds of flies and mosquitoes increased the

likelihood

of spreading communicable jungle fevers. The river Comberciato

was

reached by Mr. Heller at a

point not more than a league from its junction with the Urubamba. The

lower

course of the Comberciato is not considered dangerous to canoe

navigation, but

the valley is much narrower than the Cosireni. The width of the river

is about

150 feet and its volume is twice that of the Cosireni. The climate is

very

trying. The nights are hot. Insect pests are numerous. Mr. Heller found

that

“the forest was filled with annoying, though stingless, bees which

persisted in

attempting to roost on the countenance of any human being available.”

On the

banks of the Comberciato he found several families of savages. All the

men were

keen hunters and fishermen. Their weapons consisted of powerful bows

made from

the wood of a small palm and long arrows made of reeds and finished

with

feathers arranged in a spiral. Monkeys were

abundant.

Specimens of six distinct

genera were found, including the large red howler, inert and easily

located by

its deep, roaring bellow which can be heard for a distance of several

miles;

the giant black spider monkey, very alert, and, when frightened, fairly

flying

through the branches at astonishing speed; and a woolly monkey, black

in color,

and very intelligent in expression, frequently tamed by the savages,

who “enjoy

having them as pets but are not averse to eating them when food is

scarce.”

“The flesh of monkeys is greatly appreciated by these Indians, who

preserved

what they did not require for immediate needs by drying it over the

smoke of a

wood fire.” On the Cosireni Mr.

Maynard

noticed that one of his

Indian guides carried a package, wrapped in leaves, which on being

opened

proved to contain forty or fifty large hairless grubs or caterpillars.

The man

finally bit their heads off and threw the bodies into a small bag,

saying that

the grubs were considered a great delicacy by the savages. The Indians we met at

Espiritu

Pampa closely

resembled those seen in the lower valley. All our savages were

bareheaded and

barefooted. They live so much in the shelter of the jungle that hats

are not

necessary. Sandals or shoes would only make it harder to use the

slippery

little trails. They had seen no strangers penetrate this valley for

about ten

years, and at first kept their wives and children well secluded. Later,

when

Messrs. Hendriksen and Tucker were sent here to determine the

astronomical

position of Espiritu Pampa, the savages permitted Mr. Tucker to take

photographs of their families. Perhaps it is doubtful whether they knew

just

what he was doing. At all events they did not run away and hide.

All the men and older

boys wore

white fillets of

bamboo. The married men had smeared paint on their faces, and one of

them was

wearing the characteristic lip ornament of the Campas. Some of the

children

wore no clothing at all. Two of the wives wore long tunics like the

men. One of

them had a truly savage face, daubed with paint. She wore no fillet,

had the

best tunic, and wore a handsome necklace made of seeds and the skins of

small

birds of brilliant plumage, a work of art which must have cost infinite

pains

and the loss of not a few arrows. All the women carried babies in

little

hammocks slung over the shoulder. One little girl, not. more than six years old,

was carrying on her back a child of two, in a hammock supported from

her head

by a tump-line. It will be remembered that forest Indians nearly always

use

tump-lines so as to allow their hands free play. One of the wives was

fairer

than the others and looked as though she might have had a Spanish

ancestor. The

most savage-looking of the women was very scantily clad, wore a

necklace of

seeds, a white lip ornament, and a few rags tied around her waist. All

her children

were naked. The children of the woman with the handsome necklace were

clothed

in pieces of old tunics, and one of them, evidently her mother’s

favorite, was

decorated with bird skins and a necklace made from the teeth of monkeys. Such were the people

among whom

Tupac Amaru took

refuge when he fled from Vilcabamba. Whether he partook of such a

delicacy as

monkey meat, which all Amazonian Indians relish, but which is not eaten

by the

highlanders, may be doubted. Garcilasso speaks of

Tupac

Amaru’s preferring to

entrust himself to the hands of the Spaniards “rather than to perish of

famine.” His Indian allies lived perfectly well in a region where

monkeys

abound. It is doubtful whether they would ever have permitted Captain

Garcia to

capture the Inca had they been able to furnish Tupac with such food as

he was

accustomed to. At all events our

investigations seem to point to

the probability of this valley having been an important part of the

domain of

the last Incas. It would have been pleasant to prolong our studies, but

the

carriers were anxious to return to Pampaconas. Although they did not

have to

eat monkey meat, they were afraid of the savages and nervous as to what

use the

latter might some day make of the powerful bows and long arrows. At Conservidayoc

Saavedra

kindly took the trouble to

make some sugar for us. He poured the syrup in oblong moulds cut in a

row along

the side of a big log of hard wood. In some of the moulds his son

placed

handfuls of nicely roasted peanuts. The result was a confection or

“emergency

ration” which we greatly enjoyed on our return journey. At San Fernando we

met the pack

mules. The next day,

in the midst of continuing torrential tropical downpours, we climbed

out of the

hot valley to the cold heights of Pampaconas. We were soaked with

perspiration

and drenched with rain. Snow had been falling above the village; our

teeth

chattered like castanets. Professor Foote immediately commandeered Mrs.

Guzman’s fire and filled our tea kettle. It may be doubted whether a

more

wretched, cold, wet, and bedraggled party ever arrived at Guzman’s hut;

certainly nothing ever tasted better than that steaming hot sweet tea. ---------------------------------------

1 Titu

Cusi was an illegitimate son of Manco. His mother was not of royal

blood and

may have been a native of the warm valleys.

|