|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XIV CONSERVIDAYOC WHEN Don Pedro Duque

of Santa

Ana was helping us to

identify places mentioned in Calancha and Ocampo, the references to

“Vilcabamba

Viejo,” or Old Uilcapampa, were supposed by two of his informants to

point to a

place called Conservidayoc. Don Pedro told us that in 1902 Lopez

Torres, who

had traveled much in the montaña looking

for rubber trees, reported the discovery there of the ruins of an Inca

city.

All of Don Pedro’s friends assured us that Conservidayoc was a terrible

place

to reach. “No one now living had been there.” “It was inhabited by

savage

Indians who would not let strangers enter their villages.” When we reached

Paltaybamba,

Señor Pancorbo’s manager

confirmed what we had heard. He said further that an individual named

Saavedra

lived at Conservidayoc and undoubtedly knew all about the ruins, but

was very

averse to receiving visitors. Saavedra’s house was extremely difficult

to find.

“No one had been there recently and returned alive.” Opinions differed

as to

how far away it was. Several days later,

while

Professor Foote and I were

studying the ruins near Rosaspata, Señor Pancorbo, returning from his

rubber

estate in the San Miguel Valley and learning at Lucma of our presence

near by,

took great pains to find us and see how we were progressing. When he

learned of

our intention to search for the ruins of Conservidayoc, he asked us to

desist

from the attempt. He said Saavedra was “a very powerful man having many

Indians

under his control and living in grand state, with fifty servants, and

not at

all desirous of being visited by anybody.” The Indians were “of the

Campa

tribe, very wild and extremely savage. They use poisoned arrows and are

very

hostile to strangers.” Admitting that he had heard there were Inca

ruins near

Saavedra’s station, Señor Pancorbo still begged us not to risk our

lives by

going to look for them. By this time our

curiosity was

thoroughly aroused.

We were familiar with the current stories regarding the habits of

savage tribes

who lived in the montaña and whose

services were in great demand as rubber gatherers. We had even heard

that

Indians did not particularly like to work for Señor Pancorbo, who was

an

energetic, ambitious man, anxious to achieve many things, results which

required more laborers than could easily be obtained. We could readily

believe

there might possibly be Indians at Conservidayoc who had escaped from

the

rubber estate of San Miguel. Undoubtedly, Señor Pancorbo’s own life

would have

been at the mercy of their poisoned arrows. All over the Amazon Basin

the

exigencies of rubber gatherers had caused tribes visited with impunity

by the

explorers of the nineteenth century to become so savage and revengeful

as to

lead them to kill all white men at sight. Professor Foote and I

considered the matter in all

its aspects. We finally came to the conclusion that in view of the

specific

reports regarding the presence of Inca ruins at Conservidayoc we could

not

afford to follow the advice of the friendly planter. We must at least

make an

effort to reach them, meanwhile taking every precaution to avoid

arousing the

enmity of the powerful Saavedra and his savage retainers.

On the day following

our

arrival at the town of

Vilcabamba, the gobernador, Condoré,

taking counsel with his chief assistant, had summoned the wisest

Indians living

in the vicinity, including a very picturesque old fellow whose name,

Quispi

Cusi, was strongly reminiscent of the days of Titu Cusi. It was

explained to him

that this was a very solemn occasion and that an official inquiry was

in

progress. He took off his hat — but not his knitted cap — and

endeavored to the

best of his ability to answer our questions about the surrounding

country. It

was he who said that the Inca Tupac Amaru once lived at Rosaspata. He

had never

heard of Uilcapampa Viejo, but he admitted that there were ruins in the

montaña near Conservidayoc.

Other

Indians were questioned by Condoré. Several had heard of the ruins of

Conservidayoc, but, apparently, none of them, nor any one in the

village, had

actually seen the ruins or visited their immediate vicinity. They all

agreed

that Saavedra’s place was “at least four days’ hard journey on foot in

the montana beyond Pampaconas.” No

village

of that name appeared on any map of Peru, although it is frequently

mentioned

in the documents of the sixteenth century. Rodriguez de Figueroa, who

came to

seek an audience with Titu Cusi about 1565, says that he met Titu Cusi

at a

place called Banbaconas. He says further that the Inca came there from

somewhere down in the dense forests of the montaña

and presented him

with a macaw and two hampers of peanuts — products of a warm region. We had brought with

us the

large sheets of

Raimondi’s invaluable map which covered this locality. We also had the

new map

of South Peru and North Bolivia which had just been published by the

Royal

Geographical Society and gave a summary of all available information.

The

Indians said that Conservidayoc lay in a westerly direction from

Vilcabamba,

yet on Raimondi’s map all of the rivers which rise in the mountains

west of the

town are short affluents of the Apurimac and flow southwest. We

wondered

whether the stories about ruins at Conservidayoc would turn out to be

as barren

of foundation as those we had heard from the trustworthy foreman at

Huadquina.

One of our informants said the Inca city was called Espiritu Pampa, or

the

“Pampa of Ghosts.” Would the ruins turn out to be “ghosts”? Would they

vanish

on the arrival of white men with cameras and steel measuring tapes? No one at Vilcabamba

had seen

the ruins, but they

said that at the village of Pampaconas, “about five leagues from here,”

there

were Indians who had actually been to Conservidayoc. Our supplies were

getting

low. There were no shops nearer than Lucma; no food was obtainable from

the

natives. Accordingly,

notwithstanding

the protestations of

the hospitable gobernador, we

decided

to start immediately for Conservidayoc. At the end of a long

day’s

march up the Vilcabamba

Valley, Professor Foote, with his accustomed skill, was preparing the

evening

meal and we were both looking forward with satisfaction to enjoying

large cups

of our favorite beverage. Several years ago, when traveling on

mule-back across

the great plateau of southern Bolivia, I had learned the value of

sweet, hot

tea as a stimulant and bracer in the high Andes. At first astonished to

see how

much tea the Indian arrieros drank,

I

learned from sad experience that it was far better than cold water,

which often

brings on mountain-sickness. This particular evening, one swallow of

the hot

tea caused consternation. It was the most horrible stuff imaginable.

Examination showed small, oily particles floating on the surface.

Further

investigation led to the discovery that one of our arrieros

had that day placed our can of kerosene on top of one

of

the loads. The tin became leaky and the kerosene had dripped down into

a food

box. A cloth bag of granulated sugar had eagerly absorbed all the oil

it could.

There was no remedy but to throw away half of our supply. As I have

said, the

longer one works in the Andes the more desirable does sugar become and

the more

one seems to crave it. Yet we were unable to procure any here. After the usual

delays, caused

in part by the

difficulty of catching our mules, which had taken advantage of our

historical

investigations to stray far up the mountain pastures, we finally set

out from

the boundaries of known topography, headed for “Conservidayoc,” a vague

place

surrounded with mystery; a land of hostile savages, albeit said to

possess the

ruins of an Inca town. Our first day’s

journey was to

Pampaconas. Here and

in its vicinity the gobernador told

us he could procure guides and the half-dozen carriers whose services

we should

require for the jungle trail where mules could not be used. As the

Indians

hereabouts were averse to penetrating the wilds of Conservidayoc and

were also

likely to be extremely alarmed at the sight of men in uniform, the two gendarmes who were now accompanying us

were instructed to delay their departure for a few hours and not to

reach

Pampaconas with our pack train until dusk. The gobernador

said that if the Indians of Pampaconas caught sight of

any brass buttons coming over the hills they would hide so effectively

that it

would be impossible to secure any carriers. Apparently this was due in

part to

that love of freedom which had led them to abandon the more comfortable

towns

for a frontier village where landlords could not call on them for

forced labor.

Consequently, before the arrival of any such striking manifestations of

official authority as our gendarmes, the

gobernador and his friend

Mogrovejo

proposed to put in the day craftily commandeering the services of a

half-dozen

sturdy Indians. Their methods will be described presently. Leaving modern

Vilcabamba, we

crossed the flat,

marshy bottom of an old glaciated valley, in which one of our mules got

thoroughly mired while searching for the succulent grasses which cover

the

treacherous bog. Fording the Vilcabamba River, which here is only a

tiny brook,

we climbed out of the valley and turned westward. On the mountains

above us

were vestiges of several abandoned mines. It was their discovery in

1572 or

thereabouts which brought Ocampo and the first Spanish settlers to this

valley.

Raimondi says that he found here cobalt, nickel, silver-bearing copper

ore, and

lead sulphide. He does not mention any gold-bearing quartz. It may have

been

exhausted long before his day. As to the other minerals, the

difficulties of

transportation are so great that it is not likely that mining will be

renewed

here for many years to come. At the top of the

pass we

turned to look back and

saw a long chain of snow-capped mountains towering above and behind the

town of

Vilcabamba. We searched in vain for them on our maps. Raimondi,

followed by the

Royal Geographical Society, did not leave room enough for such a range

to exist

between the rivers Apurimac and Urubamba. Mr. Hendriksen determined our

longitude to be 73° west, and our latitude to be 13° 8’ south. Yet

according to

the latest map of this region, published in the preceding year, this

was the

very position of the river Apurimac itself, near its junction with the

river

Pampas. We ought to have been swimming “the Great Speaker.” Actually we

were on

top of a lofty mountain pass surrounded by high peaks and glaciers. The

mystery

was finally solved by Mr. Bumstead in 1912, when he determined the

Apurimac and

the Urubamba to be thirty miles farther apart than any one had

supposed. His

surveys opened an unexplored region, 1500 square miles in extent, whose

very

existence had not been guessed before 1911. It proved to be one of the

largest

undescribed glaciated areas in South America. Yet it is less than a

hundred

miles from Cuzco, the chief city in the Peruvian Andes, and the site of

a

university for more than three centuries. That Uilcapampa could so long

defy

investigation and exploration shows better than anything else how

wisely Manco

had selected his refuge. It is indeed a veritable labyrinth of

snow-clad peaks,

unknown glaciers, and trackless canyons. Looking west, we saw

in front

of us a great

wilderness of deep green valleys and forest-clad slopes. We supposed

from our

maps that we were now looking down into the basin of the Apurimac. As a

matter

of fact, we were on the rim of the valley of the hitherto uncharted

Pampaconas,

a branch of the Cosireni, one of the affluents of the Urubamba. Instead

of

being the Apurimac Basin, what we saw was another unexplored region

which

drained into the Urubamba! At the time, however,

we did

not know where we were,

but understood from Condoré that somewhere far down in the montaña

below

us was Conservidayoc, the sequestered domain of Saavedra and his savage

Indians. It seemed less likely than ever that the Incas could have

built a town

so far away from the climate and food to which they were accustomed,

The “road”

was now so bad that only with the greatest difficulty could we coax our

sure-footed mules to follow it. Once we had to dismount, as the path

led down a

long, steep, rocky stairway of ancient origin. At last, rounding a

hill, we

came in sight of a lonesome little hut perched on a shoulder of the

mountain.

In front of it, seated in the sun on mats, were two women shelling

corn. As

soon as they saw the gobernador approaching,

they stopped their work and began to prepare lunch. It was about eleven

o’clock

and they did not need to be told that Señor Condoré and his friends had

not had

anything but a cup of coffee since the night before. In order to meet

the

emergency of unexpected guests they killed four or five squealing cuys

(guinea pigs), usually to be found scurrying about the mud floor of the

huts of

mountain Indians. Before long the savory odor of roast cuy,

well basted,

and cooked-to-a-turn on primitive spits, whetted our appetites.

In the eastern United States one

sees guinea pigs only as pets or laboratory victims; never as an

article of

food. In spite of the celebrated dogma that “Pigs is Pigs,” this form

of “pork”

has never found its way to our kitchens, even though these “pigs” live

on a

very clean, vegetable diet. Incidentally guinea pigs do not come from

Guinea

and are in no way related to pigs — Mr. Ellis Parker Butler to the

contrary notwithstanding!

They belong rather to the same family as rabbits and Belgian hares and

have

long been a highly prized article of food in the Andes of Peru. The

wild

species are of a grayish brown color, which enables them to escape

observation

in their natural habitat. The domestic varieties, which one sees in the

huts of

the Indians, are piebald, black, white, and tawny, varying from one

another in

color as much as do the llamas, which were also domesticated by the

same race

of people thousands of years ago. Although Anglo-Saxon “folkways,” as

Professor

Sumner would say, permit us to eat and enjoy long-eared rabbits, we

draw the

line at short-eared rabbits, yet they were bred to be eaten. I am willing to admit

that this

was the first time

that I had ever knowingly tasted their delicate flesh, although once in

the

capital of Bolivia I thought the hotel kitchen had a diminishing

supply! Had I

not been very hungry, I might never have known how delicious a roast

guinea pig

can be. The meat is not unlike squab. To the Indians whose supply of

animal

food is small, whose fowls are treasured for their eggs, and whose thin

sheep

are more valuable as wool bearers than as mutton, the succulent guinea

pig,

“most prolific of mammals,” as was discovered by Mr. Butler’s hero, is

a highly

valued article of food, reserved for special occasions. The North

American

housewife keeps a few tins of sardines and cans of preserves on hand

for

emergencies. Her sister in the Andes similarly relies on fat little

cuys. After lunch, Condoré

and

Mogrovejo divided the

extensive rolling countryside between them and each rode quietly from

one

lonesome farm to another, looking for men to engage as bearers. When

they were

so fortunate as to find the man of the house at home or working in his

little

chacra they greeted him pleasantly. When he came forward to shake

hands, in the

usual Indian manner, a silver dollar was unsuspectingly slipped into

the palm

of his right hand and he was informed that he had accepted pay for

services

which must now be performed. It seemed hard, but this was the only way

in which

it was possible to secure carriers. During Inca times the

Indians

never received pay for

their labor. A paternal government saw to it that they were properly

fed and

clothed and either given abundant opportunity to provide for their own

necessities or else permitted to draw on official stores. In colonial

days a

more greedy and less paternal government took advantage of the ancient

system

and enforced it without taking pains to see that it should not cause

suffering.

Then, for generations, thoughtless landlords, backed by local

authority, forced

the Indians to work without suitably recompensing them at the end of

their

labors or even pretending to carry out promises and wage agreements.

The peons

learned that it was unwise to perform any labor without first having

received a

considerable portion of their pay. When once they accepted money,

however,

their own custom and the law of the land provided that they must carry

out

their obligations. Failure to do so meant legal punishment. Consequently, when an

unfortunate Pampaconas Indian

found he had a dollar in his hand, he bemoaned his fate, but realized

that

service was inevitable. In vain did he plead that he was “busy,” that

his

“crops needed attention,” that his “family could not spare him,” that

“he

lacked food for a journey.” Condoré and Mogrovejo were accustomed to

all

varieties of excuses. They succeeded in “engaging” half a dozen

carriers.

Before dark we reached the village of Pampaconas, a few small huts

scattered

over grassy hillsides, at an elevation of 10,000 feet. In the notes of one

of the

military advisers of

Viceroy Francisco dc Toledo is a reference to Pampaconas as a “high,

cold

place.” This is correct. Nevertheless, I doubt if the present village

is the

Pampaconas mentioned in the documents of Garcia’s day as being “an

important

town of the Incas.” There are no ruins hereabouts. The huts of

Pampaconas were

newly built of stone and mud, and thatched with grass. They were

occupied by a

group of sturdy mountain Indians, who enjoyed unusual freedom from

official or

other interference and a good place in which to raise sheep and

cultivate

potatoes, on the very edge of the dense forest. We found that there was

some

excitement in the village because on the previous night a jaguar, or

possibly a

cougar, had come out of the forest, attacked, killed, and dragged off

one of

the village ponies. We were conducted to

the

dwelling of a stocky,

well-built Indian named Guzman, the most reliable man in the village,

who had

been selected to be the head of the party of carriers that was to

accompany us

to Conservidayoc. Guzman had some Spanish blood in his veins, although

he did

not boast of it. With his wife and six children he occupied one of the

best

huts. A fire in one corner frequently filled it with acrid smoke. It

was very small

and had no windows. At one end was a loft where family treasures could

be kept

dry and reasonably safe from molestation. Piles of sheep skins were

arranged

for visitors to sit upon. Three or four rude niches in the walls served

in lieu

of shelves and tables. The floor of well-trodden clay was damp. Three

mongrel

dogs and a flea-bitten cat were welcome to share the narrow space with

the

family and their visitors. A dozen hogs entered stealthily and tried to

avoid

attention by putting a muffler on involuntary grunts. They did not

succeed and

were violently ejected by a boy with a whip; only to return again and

again,

each time to be driven out as before, squealing loudly. Notwithstanding these

interruptions, we carried on a

most interesting conversation with Guzman. He had been to Conservidayoc

and had

himself actually seen ruins at Espiritu Pampa. At last the mythical

“Pampa of

Ghosts” began to take on in our minds an aspect of reality, even though

we were

careful to remind ourselves that another very trustworthy man had said

he had

seen ruins “finer than Ollantaytambo” near Huadquina. Guzman did not

seem to

dread Conservidayoc as much as the other Indians, only one of whom had

ever

been there. To cheer them up we purchased a fat sheep, for which we

paid fifty

cents. Guzman immediately butchered it in preparation for the journey.

Although

it was August and the middle of the dry season, rain began to fall

early in the

afternoon. Sergeant Carrasco arrived after dark with our pack animals,

but,

missing the trail as he neared Guzman’s place, one of the mules stepped

into a

bog and was extracted only with considerable difficulty. We decided to

pitch

our small pyramidal tent on a fairly well-drained bit of turf not far

from

Guzman’s little hut. In the evening, after we had had a long talk with

the

Indians, we came back through the rain to our comfortable little tent,

only to

hear various and sundry grunts emerging therefrom. We found that during

our

absence a large sow and six fat young pigs, unable to settle down

comfortably

at the Guzman hearth, had decided that our tent was much the driest

available

place on the mountain side and that our blankets made a particularly

attractive

bed. They had considerable difficulty in getting out of the small door

as fast

as they wished. Nevertheless, the pouring rain and the memory of

comfortable

blankets caused the pigs to return at intervals. As we were starting to

enjoy

our first nap, Guzman, with hospitable intent, sent us two bowls of

steaming

soup, which at first glance seemed to contain various sizes of white

macaroni —

a dish of which one of us was particularly fond. The white hollow

cylinders

proved to be extraordinarily tough, not the usual kind of macaroni. As

a matter

of fact, we learned that the evening meal which Guzman’s wife had

prepared for

her guests was made chiefly of sheep’s entrails!

Rain continued

without intermission during the whole of a very cold and dreary night.

Our

tent, which had never been wet before, leaked badly; the only part

which seemed

to be thoroughly waterproof was the floor. As day dawned we found

ourselves to

be lying in puddles of water. Everything was soaked. Furthermore, rain

was

still falling. While we were discussing the situation and wondering

what we

should cook for breakfast, the faithful Guzman heard our voices and

immediately

sent us two more bowls of hot soup, which were this time more welcome,

even

though among the bountiful corn, beans, and potatoes we came

unexpectedly upon

fragments of the teeth and jaws of the sheep. Evidently in Pampaconas

nothing

is wasted. We were anxious to

make an

early start for

Conservidayoc, but it was first necessary for our Indians to prepare

food for

the ten days’ journey ahead of them. Guzman’s wife, and I suppose the

wives of

our other carriers, spent the morning grinding chuño

(frozen potatoes)

with a rocking stone pestle on a flat stone mortar, and parching or

toasting

large quantities of sweet corn in a terra-cotta olla. With chuño

and tostado, the body of the

sheep, and a

small quantity of coca leaves, the Indians

professed themselves to be

perfectly contented. Of our own provisions we had so small a quantity

that we

were unable to spare any. However, it is doubtful whether the Indians

would

have liked them as much as the food to which they had long been

accustomed. Toward noon, all the

Indian

carriers but one having

arrived, and the rain having partly subsided, we started for

Conservidayoc. We

were told that it would be possible to use the mules for this day’s

journey.

San Fernando, our first stop, was “seven leagues” away, far down in the

densely

wooded Pampaconas Valley. Leaving the village we climbed up the

mountain back

of Guzman’s hut and followed a faint trail by a dangerous and

precarious route

along the crest of the ridge. The rains had not improved the path. Our

saddle

mules were of little use. We had to go nearly all the way on foot.

Owing to

cold rain and mist we could see but little of the deep canyon which

opened

below us, and into which we now began to descend through the clouds by

a very

steep, zigzag path, four thousand feet to a hot tropical valley. Below

the

clouds We found ourselves near a small abandoned clearing. Passing this

and

fording little streams, we went along a very narrow path, across steep

slopes,

on which maize had been planted. Finally we came to another little

clearing and

two extremely primitive little shanties, mere shelters not deserving to

be

called huts; and this was San Fernando, the end of the mule trail.

There was

scarcely room enough in them for our six carriers. It was with great

difficulty

we found and cleared a place for our tent, although its floor was only

seven

feet square. There was no really flat land at all. At 8:30 P.M. August

13, 1911,

while lying on the

ground in our tent, I noticed an earthquake. It was felt also by the

Indians in

the near-by shelter, who from force of habit rushed out of their frail

structure and made a great disturbance, crying out that there was a temblor. Even had their little thatched

roof fallen upon them, as it might have done during the stormy night

which

followed, they were in no danger; but, being accustomed to the stone

walls and

red tiled roofs of mountain villages where earthquakes sometimes do

very

serious harm they were greatly excited. The motion seemed to me to be

like a

slight shuffle from west to east, lasting three or four seconds, a

gentle

rocking back and forth, with eight or ten vibrations. Several weeks

later, near

Huadquina, we happened to stop at the Colpani telegraph office. The

operator

said he had felt two shocks on August 13 — one at five o’clock, which

had

shaken the books off his table and knocked over a box of insulators

standing

along a wall which ran north and south. He said the shock which I had

felt was

the lighter of the two. During the night it

rained

hard, but our tent was

now adjusting itself to the “dry season” and we were more comfortable.

Furthermore, camping out at 10,000 feet above sea level is very

different from

camping at 6000 feet. This elevation, similar to that of the bridge of

San Miguel,

below Machu Picchu, is on the lower edge of the temperate zone and the

beginning of the torrid tropics. Sugar cane, peppers, bananas, and

grenadillas

grow here as well as maize, squashes, and sweet potatoes. None of these

things

will grow at Pampaconas. The Indians who raise sheep and white potatoes

in that

cold region come to San Fernando to make chacras or small clearings.

The three

or four natives whom we found here were so alarmed by the sight of

brass

buttons that they disappeared during the night rather than take the

chance of

having a silver dollar pressed into their hands in the morning! From

San

Fernando, we sent one of our gendarmes back

to Pampaconas with the mules. Our carriers were good for about fifty

pounds

apiece. Half an hour’s walk

brought us

to Vista Alegre,

another little clearing on an alluvial fan in the bend of the river.

The soil

here seemed to be very rich. In the chacra we saw corn stalks eighteen

feet in

height, near a gigantic tree almost completely enveloped in the embrace

of a

mato-palo, or parasitic fig tree. This clearing certainly deserves its

name,

for it commands a “charming view” of the green Pampaconas Valley.

Opposite us

rose abruptly a heavily forested mountain, whose summit was lost in the

clouds

a mile above. To circumvent this mountain the river had been flowing in

a

westerly direction; now it gradually turned to the northward. Again we

were

mystified; for, by Raimondi’s map, it should have gone southward. We entered a dense

jungle,

where the narrow path

became more and more difficult for our carriers. Crawling over rocks,

under

branches, along slippery little cliffs, on steps which had been cut in

earth or

rock, over a trail which not even dogs could follow unassisted, slowly

we made

our way down the valley. Owing to the heat, humidity, and the frequent

showers,

it was mid-afternoon before we reached another little clearing called

Pacaypata. Here, on a hillside nearly a thousand feet above the river,

our men

decided to spend the night in a tiny little shelter six feet long and

five feet

wide. Professor Foote and I had to dig a shelf out of the steep

hillside in

order to pitch our tent. The next morning, not

being

detained by the vagaries

of a mule train, we made an early start. As we followed the faint

little trail

across the gulches tributary to the river Pampaconas, we had to

negotiate

several unusually steep descents and ascents. The bearers suffered from

the

heat. They found it more and more difficult to carry their loads. Twice

we had

to cross the rapids of the river on primitive bridges which consisted

only of a

few little logs lashed together and resting on slippery boulders. By one o’clock we

found

ourselves on a small plain

(ele. 4500 ft.) in dense woods surrounded by tree ferns, vines, and

tangled

thickets, through which it was impossible to see for more than a few

feet. Here

Guzman told us we must stop and rest a while, as we were now in the

territory

of los salvajes, the savage

Indians

who acknowledged only the rule of Saavedra and resented all intrusion.

Guzman

did not seem to be particularly afraid, but said that we ought to send

ahead

one of our carriers, to warn the savages that we were coming on a

friendly

mission and were not in search of rubber gatherers; otherwise they

might attack

us, or run away and disappear into the jungle. He said we should never

be able

to find the ruins without their help. The carrier who was selected to

go ahead

did not relish his task. Leaving his pack behind, he proceeded very

quietly and

cautiously along the trail and was lost to view almost immediately.

There

followed an exciting half-hour while we waited, wondering what attitude

the

savages would take toward us, and trying to picture to ourselves the

mighty

potentate, Saavedra, who had been described as sitting in the midst of

savage

luxury, “surrounded by fifty servants,” and directing his myrmidons to

checkmate our desires to visit the Inca city on the “pampa of ghosts.” Suddenly, we were

startled by

the crackling of twigs

and the sound of a man running. We instinctively held our rifles a

little

tighter in readiness for whatever might befall — when there burst out

of the

woods a pleasant-faced young Peruvian, quite conventionally clad, who

had come

in haste from Saavedra, his father, to extend to us a most cordial

welcome! It

seemed scarcely credible, but a glance at his face showed that there

was no

ambush in store for us. It was with a sigh of relief that we realized

there was

to be no shower of poisoned arrows from the impenetrable thickets.

Gathering up

our packs, we continued along the jungle trail, through woods which

gradually

became higher, deeper, and darker, until presently we saw sunlight

ahead and,

to our intense astonishment, the bright green of waving sugar cane. A

few

moments of walking through the cane fields found us at a large

comfortable hut,

welcomed very simply and modestly by Saavedra himself. A more pleasant

and

peaceable little man it was never my good fortune to meet. We looked

furtively

around for his fifty savage servants, but all we saw was his

good-natured

Indian wife, three or four small children, and a wild-eyed

maid-of-all-work,

evidently the only savage present. Saavedra said some called this place

“Jesús

Maria” because they were so surprised when they saw it. It is difficult to

describe our

feelings as we

accepted Saavedra’s invitation to make ourselves at home, and sat down

to an

abundant meal of boiled chicken, rice, and sweet cassava (manioc).

Saavedra

gave us to understand that we were not only most welcome to anything he

had,

but that he would do everything to enable us to see the ruins, which

were, it

seemed, at Espiritu Pampa, some distance farther down the valley, to be

reached

only by a hard trail passable for barefooted savages, but scarcely

available

for us unless we chose to go a good part of the distance on hands and

knees.

The next day, while our carriers were engaged in clearing this trail,

Professor

Foote collected a large number of insects, including eight new species

of moths

and butterflies. I

inspected Saavedra’s plantation. The soil having

lain fallow for centuries, and being rich in humus, had produced more

sugar

cane than he could grind. In addition to this, he had bananas, coffee

trees,

sweet potatoes, tobacco, and peanuts. Instead of being “a

very powerful chief

having many Indians under his control” — a kind of

“Pooh-Bah” — he was merely a

pioneer. In the utter wilderness, far from any neighbors, surrounded by

dense

forests and a few savages, he had established his home. He was not an

Indian

potentate, but only a frontiersman, soft-spoken and energetic, an

ingenious

carpenter and mechanic, a modest Peruvian of the best type. Owing to the scarcity

of arable

land he was obliged

to cultivate such pampas as he could find — one an

alluvial fan near his

house, another a natural terrace near the river. Back of the house was

a

thatched shelter under which he had constructed a little sugar mill. It

had a

pair of hardwood rollers, each capable of being turned, with much

creaking and

cracking, by a large, rustic wheel made of roughly hewn timbers

fastened

together with wooden pins and lashed with thongs, worked by hand and

foot

power. Since Saavedra had been unable to coax any pack animals over the

trail

to Conservidayoc he was obliged to depend entirely on his own limited

strength and

that of his active son, aided by the uncertain and irregular services

of such

savages as wished to work for sugar, trinkets, or other trade articles.

Sometimes the savages seemed to enjoy the fun of climbing on the great

creaking

treadwheel, as though it were a game. At other times they would

disappear in

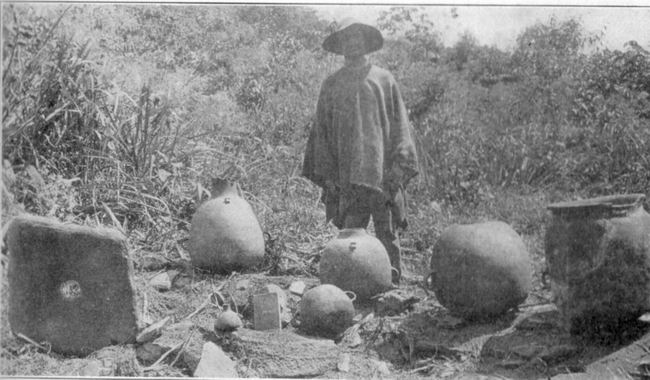

the woods. Near the mill were

some

interesting large pots which

Saavedra was using in the process of boiling the juice and making crude

sugar.

He said he had found the pots in the jungle not far away. They had been

made by

the Incas. Four of them were of the familiar aryballus

type. Another was of a closely related form, having a

wide mouth, pointed base, single incised, conventionalized, animal-head

nubbin

attached to the shoulder, and band-shaped handles attached vertically

below the

median line. Although capable of holding more than ten gallons, this

huge pot

was intended to be carried on the back and shoulders by means of a rope

passing

through the handles and around the nubbin. Saavedra said that he had

found near

his house several bottle-shaped cists lined with stones, with a flat

stone on

top — evidently ancient graves. The bones had entirely disappeared. The

cover

of one of the graves had been pierced; the hole covered with a thin

sheet of

beaten silver. He had also found a few stone implements and two or

three small

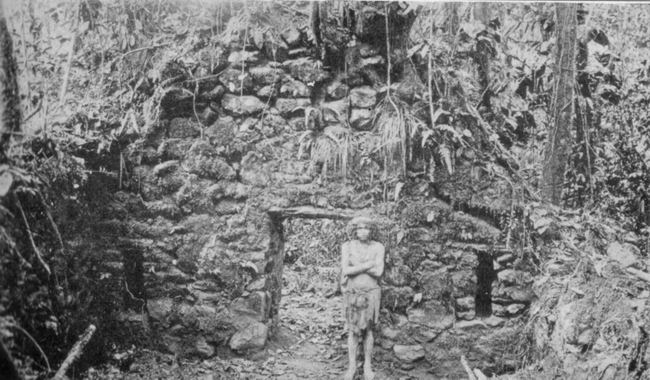

bronze Inca axes.  SAAVEDRA AND HIS INCA POTTERY  INCA GABLE AT ESPIRITU PAMPA On the pampa,

below

his house, Saavedra had constructed with infinite labor another sugar

mill. It

seemed strange that he should have taken the trouble to make two mills;

but

when one remembered that he had no pack animals and was usually obliged

to

bring the cane to the mill on his own back and the back of his son, one

realized that it was easier, while the cane was growing, to construct a

new

mill near the cane field than to have to carry the heavy bundles of

ripe cane

up the hill. He said his hardest task was to get money with which to

send his

children to school in Cuzco and to pay his taxes. The only way in which

he

could get any cash was by making chancaca,

crude brown sugar, and carrying it on his back, fifty

pounds at a time,

three hard days’ journey on foot up the mountain to Pampaconas or

Vilcabamba,

six or seven thousand feet above his little plantation. He said he

could

usually sell such a load for five soles, equivalent

to two dollars and a

half! His was certainly a hard lot, but he did not complain, although

he

smilingly admitted that it was very difficult to keep the trail open,

since the

jungle grew so fast and the floods in the river continually washed away

his

little rustic bridges. His chief regret was that as the result of a

recent

revolution, with which he had had nothing to do, the government had

decreed

that all firearms should be turned in, and so he had lost the one thing

he

needed to enable him to get fresh meat in the forest. In the clearing

near the

house we were interested to see a large turkey-like bird, the pava

de la

montãna, glossy black, its most striking feature a high,

coral red comb.

Although completely at liberty, it seemed to be thoroughly

domesticated. It

would make an attractive bird for introduction into our Southern States. Saavedra gave us

some very

black leaves of native

tobacco, which he had cured. An inveterate smoker who tried it in his

pipe said

it was without exception the strongest stuff he ever had encountered! So interested did I

become in

talking with Saavedra,

seeing his plantation, and marveling that he should be worried about

taxes and

have to obey regulations in regard to firearms, I had almost forgotten

about

the wild Indians. Suddenly our carriers ran toward the house in a great

flurry

of excitement, shouting that there was a “savage” in the bushes near

by. The

“wild man” was very timid, but curiosity finally got the better of fear

and he

summoned up sufficient courage to accept Saavedra’s urgent invitation

that he

come out and meet us. He proved to be a miserable specimen, suffering

from a

very bad cold in his head. It has been my good fortune at one time or

another

to meet primitive folk in various parts of America and the Pacific, but

this

man was by far the dirtiest and most wretched savage that I have ever

seen. He was dressed in a

long,

filthy tunic which came

nearly to his ankles. It was made of a large square of coarsely woven

cotton

cloth, with a hole in the middle for his head. The sides were stitched

up,

leaving holes for the arms. His hair was long, unkempt, and matted. He

had

small, deep-set eyes, cadaverous cheeks, thick lips, and a large mouth.

His big

toes were unusually long and prehensile. Slung over one shoulder he

carried a

small knapsack made of coarse fiber net. Around his neck hung what at

first

sight seemed to be a necklace composed of a dozen stout cords securely

knotted

together. Although I did not see it in use, I was given to understand

that when

climbing trees, he used this stout loop to fasten his ankles together

and thus

secure a tighter grip for his feet. By evening two other

savages

had come in; a young

married man and his little sister. Both had bad colds. Saavedra told us

that

these Indians were Pichanguerras, a subdivision of the Campa tribe.

Saavedra

and his son spoke a little of their language, which sounded to our

unaccustomed

ears like a succession of low grunts, breathings, and gutturals. It was

pieced

out by signs. The long tunics worn by the men indicated that they had

one or

more wives. Before marrying they wear very scanty attire — nothing more

than a

few rags hanging over one shoulder and tied about the waist. The long

tunic, a

comfortable enough garment to wear during the cold nights, and their

only

covering, must impede their progress in the jungle; yet they live

partly by

hunting, using bows and arrows. We learned that these Pichanguerras had

run

away from the rubber country in the lower valleys; that they found it

uncomfortably cold at this altitude, 4500 feet, but preferred freedom

in the

higher valleys to serfdom on a rubber estate. Saavedra said that he

had named

his plantation Conservidayoc, because

it was in truth

“a spot where one may be preserved from harm.” Such was the home of the

potentate from whose abode “no one had been known to return alive.” |