|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XVI THE STORY OF TAMPU-TOCCO, A LOST CITY OF THE FIRST INCAS It will be remembered

that

while on the search for

the capital of the last Incas we had found several groups of ruins

which we

could not fit entirely into the story of Manco and his sons. The most

important

of these was Machu Picchu. Many of its buildings are far older than the

ruins

of Rosaspata and Espiritu Pampa. To understand just what we may have

found at

Machu Picchu it is now necessary to tell the story of a celebrated

city, whose

name, Tampu-tocco, was not used even at the time of the Spanish

Conquest as the

cognomen of any of the Inca towns then in existence. I must draw the

reader’s

attention far away from the period when Pizarro and Manco, Toledo and

Tupac

Amaru were the protagonists, back to events which occurred nearly seven

hundred

years before their day. The last Incas ruled in Uiticos between 1536

and 1572.

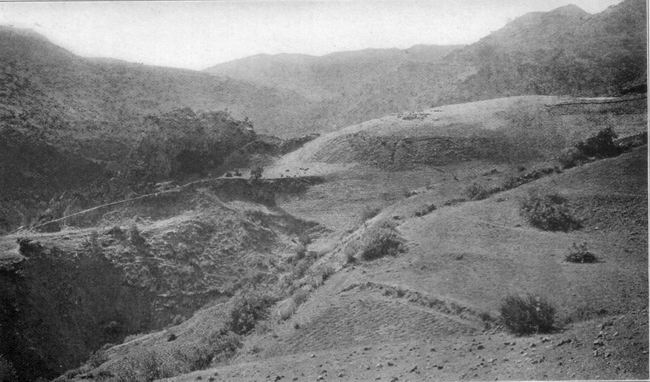

The last Amautas flourished about 800 A.D.  PUMA URCO, NEAR PACCARITAMPU The Amautas had been

ruling the

Peruvian highlands

for about sixty generations, when, as has been told in Chapter VI,

invaders

came from the south and east. The Amautas had built up a wonderful

civilization. Many of the agricultural and engineering feats which we

ordinarily assign to the Incas were really achievements of the Amautas.

The

last of the Amautas was Pachacuti VI, who was killed by an arrow on the

battle-field of La Raya. The historian Montesinos, whose work on the

antiquities of Peru has recently been translated for the Hakluyt

Society by Mr.

P. A. Means, of Harvard University, tells us that the followers of

Pachacuti VI

fled with his body to “Tampu-tocco.” This, says the historian, was “a

healthy

place” where there was a cave in which they hid the Amauta’s body.

Cuzco, the

finest and most important of all their cities, was sacked. General

anarchy

prevailed throughout the ancient empire. The good old days of peace and

plenty

disappeared before the invader. The glory of the old empire was

destroyed, not

to return for several centuries. In these dark ages, resembling those

of

European medieval times which followed the Germanic migrations and the

fall of

the Roman Empire, Peru was split up into a large number of small

independent

units. Each district chose its own ruler and carried on depredations

against

its neighbors. The effects of this may still be seen in the ruins of

small

fortresses found guarding the way into isolated Andean valleys. Montesinos says that

those who

were most loyal to

the Amautas were few in number and not strong enough to oppose their

enemies

successfully. Some of them, probably the principal priests, wise men,

and

chiefs of the ancient régime, built a new city at “Tampu-tocco.” Here

they kept

alive the memory of the Amautas and lived in such a relatively

civilized manner

as to draw to them, little by little, those who wished to be safe from

the

prevailing chaos and disorder and the tyranny of the independent chiefs

or

“robber barons.” In their new capital, they elected a king, Titi

Truaman

Quicho. The survivors of the old regime enjoyed living at Tampu-tocco,

because

there never have been any earthquakes, plagues, or tremblings there.

Furthermore, if fortune should turn against their new young king, Titi

Truaman,

and he should be killed, they could bury him in a very sacred place,

namely,

the cave where they hid the body of Pachacuti VI. Fortune was kind to

the

founders of the new kingdom. They had chosen an excellent place of

refuge where

they were not disturbed. To their ruler, the king of Tampu-tocco, and

to his

successors nothing worth recording happened for centuries. During this

period

several of the kings wished to establish themselves in ancient Cuzco,

where the

great Amautas had reigned, but for one reason or another were obliged

to forego

their ambitions. One of the most

enlightened

rulers of Tampu-tocco

was a king called Tupac Cauri, or Pachacuti VII. In his day people

began to

write on the leaves of trees. He sent messengers to the various parts

of the

highlands, asking the tribes to stop worshiping idols and animals, to

cease

practicing evil customs which had grown up since the fall of the

Amautas, and

to return to the ways of their ancestors. He met with little

encouragement. On

the contrary, his ambassadors were killed and little or no change took

place.

Discouraged by the failure of his attempts at reformation and desirous

of

learning its cause, Tupac Cauri was told by his soothsayers that the

matter

which most displeased the gods was the invention of writing. Thereupon

he

forbade anybody to practice writing, under penalty of death. This

mandate was

observed with such strictness that the ancient folk never again used

letters.

Instead, they used quipus, strings and knots. It

was supposed that the

gods were appeased, and every one breathed easier. No one realized how

near the

Peruvians as a race had come to taking a most momentous step. This curious and

interesting

tradition relates to an

event supposed to have occurred many centuries before the Spanish

Conquest. We

have no ocular evidence to support it. The skeptic may brush it aside

as a

story intended to appeal to the vanity of persons with Inca blood in

their

veins; yet it is not told by the half-caste Garcilasso, who wanted

Europeans to

admire his maternal ancestors and wrote his book accordingly, but is in

the

pages of that careful investigator Montesinos, a pure-blooded Spaniard.

As a

matter of fact, to students of Sumner’s “Folkways,” the story rings

true. Some

young fellow, brighter than the rest, developed a system of ideographs

which he

scratched on broad, smooth leaves. It worked. People were beginning to

adopt

it. The conservative priests of Tampu-tocco did not like it. There was

danger

lest some of the precious secrets, heretofore handed down orally to the

neophytes, might become public property. Nevertheless, the invention

was so

useful that it began to spread. There followed some extremely unlucky

event —

the ambassadors were killed, the king’s plans miscarried. What more

natural

than that the newly discovered ideographs should be blamed for it? As a

result,

the king of Tampu-tocco, instigated thereto by the priests, determined

to

abolish this new thing. Its usefulness had not yet been firmly

established. In

fact it was inconvenient; the leaves withered, dried, and cracked, or

blew

away, and the writings were lost. Had the new invention been permitted

to exist

a little longer, some one would have commenced to scratch ideographs on

rocks.

Then it would have persisted. The rulers and priests, however, found

that the

important records of tribute and taxes could be kept perfectly well by

means of

the quipus. And the “job” of those whose duty it

was to remember what

each string stood for was assured. After all there is nothing unusual

about

Montesinos’ story. One has only to look at the history of Spain itself

to

realize that royal bigotry and priestly intolerance have often crushed

new

ideas and kept great nations from making important advances. Montesinos says

further that

Tupac Cauri established

in Tampu-tocco a kind of university where boys were taught the use of quipus,

the method of counting and the significance of the different colored

strings,

while their fathers and older brothers were trained in military

exercises — in

other words, practiced with the sling, the bolas and the war-club;

perhaps also

with bows and arrows. Around the name of Tupac Cauri, or Pachacuti VII,

as he

wished to be called, is gathered the story of various intellectual

movements

which took place in Tampu-tocco. Finally, there came a time when the

skill and

military efficiency of the little kingdom rose to a high plane. The

ruler and

his councilors, bearing in mind the tradition of their ancestors who

centuries

before had dwelt in Cuzco, again determined to make the attempt to

reestablish

themselves there. An earthquake, which ruined many buildings in Cuzco,

caused

rivers to change their courses, destroyed towns, and was followed by

the

outbreak of a disastrous epidemic. The chiefs were obliged to give up

their

plans, although in healthy Tampu-tocco there was no pestilence. Their

kingdom

became more and more crowded. Every available square yard of arable

land was

terraced and cultivated. The men were intelligent, well organized, and

accustomed to discipline, but they could not raise enough food for

their

families; so, about 1300 A.D., they were forced to secure arable land

by

conquest, under the leadership of the energetic ruler of the day. His

name was

Manco Ccapac, generally called the first Inca, the ruler for whom the

Manco of

1536 was named. There are many stories of the rise of the first Inca. When he had grown to man’s estate, he assembled his people to see how he could secure new lands for them. After consultation with his brothers, he determined to set out with them “toward the hill over which the sun rose,” as we are informed by Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamayhua, an Indian who was a descendant of a long line of Incas, whose great-grandparents lived in the time of the Spanish Conquest, and who wrote an account of the antiquities of Peru in 1620. He gives the history of the Incas as it was handed down to the descendants of the former rulers of Peru. In it we read that Manco Ccapac and his brothers finally succeeded in reaching Cuzco and settled there. With the return of the descendants of the Amautas to Cuzco there ended the glory of Tampu-tocco. Manco married his own sister in order that he might not lose caste and that no other family be elevated by this marriage to be on an equality with his. He made good laws, conquered many provinces, and is regarded as the founder of the Inca dynasty. The highlanders came under his sway and brought him rich presents. The Inca, as Manco Ccapac now came to be known, was recognized as the most powerful chief, the most valiant fighter, and the most lucky warrior in the Andes. His captains and soldiers were brave, well disciplined, and well armed. All his affairs prospered greatly. “Afterward he ordered works to be executed at the place of his birth, consisting of a masonry wall with three windows, which were emblems of the house of his fathers whence he descended. The first window was called Tampu-tocco.” I quote from Sir Clements Markham’s translation.

The Spaniards who

asked about

Tampu-tocco were told

that it was at or near Paccaritampu, a small town eight or ten miles

south of

Cuzco. I learned that ruins are very scarce in its vicinity. There are

none in

the town. The most important are the ruins of Maucallacta, an Inca

village, a

few miles away. Near it I found a rocky hill consisting of several

crags and

large rocks, the surface of one of which is carved into platforms and

two

sleeping pumas. It is called Puma Urco. Beneath the rocks are some

caves. I was

told they had recently been used by political refugees. There is enough

about

the caves and the characteristics of the ruins near Paccaritampu to

lend color

to the story told to the early Spaniards. Nevertheless, it would seem

as if

Tampu-tocco must have been a place more remote from Cuzco and better

defended

by Nature from any attacks on that side. How else would it have been

possible

for the disorganized remnant of Pachacuti VI’s army to have taken

refuge there

and set up an independent kingdom in the face of the warlike invaders

from the

south? A few men might have hid in the caves of Puma Urco, but

Paccaritampu is

not a natural citadel. The surrounding

region is not

difficult of access.

There are no precipices between here and the Cuzco Basin. There are no

natural

defenses against such an invading force as captured the capital of the

Amautas.

Furthermore, tampu means “a place of temporary

abode,” or “a tavern,” or

“an improved piece of ground” or “farm far from a town”; tocco

means

“window.” There is an old tavern at Maucallacta near Paccaritampu, but

there

are no windows in the building to justify the name of “window tavern”

or “place

of temporary abode” (or “farm far from a town”) “noted for its

windows.” There

is nothing of a “masonry wall with three windows “ corresponding to

Salcamayhua’s description of Manco Ccapac’s memorial at his birthplace.

The

word “Tampu-tocco” does not occur on any map I have been able to

consult, nor

is it in the exhaustive gazetteer of Peru compiled by Paz Soldan. |