|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

THESE wasps dig tunnels in the ground. One sees

them, in the hottest part of the summer, working as if the intense heat were the

power that put them in motion. The hotter the day, the more fiercely they work,

and when not digging they are flying swiftly about as if looking for some-thing

they were in desperate need of finding, and finding right away, One cannot help

noticing them, particularly as some of them are of very large size and present a

most formidable appearance. They are all harmless, however, if let alone. The

solitary wasp will never go out of its way to sting. Queens, whether bees or

wasps, do not carelessly risk the loss of the sting, which is also the

ovipositor, its loss entailing the destruction of the mother insect, and of

course of her possible progeny. The solitary female wasps are all “queens”; that

is, all perfect, egg-laying females.

THESE wasps dig tunnels in the ground. One sees

them, in the hottest part of the summer, working as if the intense heat were the

power that put them in motion. The hotter the day, the more fiercely they work,

and when not digging they are flying swiftly about as if looking for some-thing

they were in desperate need of finding, and finding right away, One cannot help

noticing them, particularly as some of them are of very large size and present a

most formidable appearance. They are all harmless, however, if let alone. The

solitary wasp will never go out of its way to sting. Queens, whether bees or

wasps, do not carelessly risk the loss of the sting, which is also the

ovipositor, its loss entailing the destruction of the mother insect, and of

course of her possible progeny. The solitary female wasps are all “queens”; that

is, all perfect, egg-laying females.

The wasps that dig in the ground have long legs furnished with spines or brushes of hairs, by means of which they dig holes or brush away or smooth over the earth at the entrance to their nests. They are very energetic creatures, some of them completing a tunnel three or four inches long in an hour or two, though some are more deliberate by nature and spend a day or two completing their underground nurseries. Sometimes they use their jaws not only to loosen the earth, but to remove it from the entrance to the nest. Even here the legs are more or less useful in kicking away the debris at the doorway, or brushing up and smoothing over the entrance to the hole when it is finally closed, and the careful mother wishes to conceal it.

Some species use the legs far more than the jaws in excavating, and some of these get down to their work very much after the fashion of a dog digging out a woodchuck's hole. They scratch out the dirt with such rapidity that it issues in a little jet or stream behind them.

There are a great many species of them, and while some are quite small, others are the giants of the wasp race.

Sometimes she has to climb several trees before getting home. Her tunnel ends in a pocket, where she places the cicada on its back, lays a long white egg on the under side of it, and closing the cell leaves her progeny to hatch out and enjoy a cicada diet until it is ready to transform, which it does after the fashion of wasps, making for itself a silken cocoon and spending the winter in its snug cell under ground.

In Mexico lives an enormous digger-wasp that provisions its nest with spiders; not with the harmless fly-catching denizens of the circular webs, however; its royal prey is none other than the great hairy tarantula, or trap-door spider, that makes a hole in the ground and covers it with a door which it can open or close at pleasure. The wasp that provides this expensive pabulum for its larvae is commonly known as the “tarantula hawk,” and many a battle royal is fought between the fierce, swift wasp and the equally fierce and powerful spider. If the spider wins, as sometimes happens, the wasp supplies her hairy highness with a hard-earned meal. If the wasp wins the great spider is stung to paralysis, dragged away, and stored in the underground nest of the wasp, to become food for the larva that hatches out of the egg laid upon the spider. If food influences character, no wonder the larvae fed upon such nutriment develop into the fiercest of their kind.

More common than these great wasps is the beautiful Sphex ichneumonea, a large wasp with a long and slender waist and wearing a yellow, velvety jacket. Its legs and wings are golden brown, as is also the big end of the abdomen, the sting end being dark brown or black.

It is a striking-looking insect as one sees it

flying among the fall flowers. It digs very rapidly when once it has selected a

spot, and hums as it works. Although it loosens the earth particle by particle

with its jaws, which are long, slender, and sickle-shaped, it also uses its legs

to carry away the debris. The earth is borne some distance from the nest and

then dropped, though that which collects about the entrance hole is kicked

vigorously aside when the accumulation exceeds what her ladyship considers

proper limits.

It is a striking-looking insect as one sees it

flying among the fall flowers. It digs very rapidly when once it has selected a

spot, and hums as it works. Although it loosens the earth particle by particle

with its jaws, which are long, slender, and sickle-shaped, it also uses its legs

to carry away the debris. The earth is borne some distance from the nest and

then dropped, though that which collects about the entrance hole is kicked

vigorously aside when the accumulation exceeds what her ladyship considers

proper limits.

When the tunnel is deep enough Madam Sphex flies away, but as a rule not far, for the grass about is alive with grasshoppers, and it does not take the brilliant, strong, and merciless creature long to select one, upon which she pounces. The grasshopper is quite helpless before the fate that has overtaken it, and yields its life with scarcely a protesting struggle. Having been stung and thus instantly paralysed, it is carried to the nest, dragged in, and shut up there with the egg of the wasp; for, having deposited her treasure within and laid the egg, Sphex scratches earth into the open end with her legs, very much as a dog might.

That wasps are possessed of strong maternal feeling can be shown by interfering with their unfinished nests, when their distress lest misfortune overtake their eggs appears as great as that of many creatures whose progeny is about them, needing their personal care.

Once the nest of Sphex ichneumonea was dug up before the mother had quite finished filling the entrance with earth. The marauders, who wished to examine the contents of the nest, say, --

“We had not supposed that the digging up of her nest would much disturb our Sphex, since her connection with it was so nearly at an end, but in this we were mistaken. When we returned to the garden about half an hour after we had done the deed, we heard her loud and anxious humming from a distance. She was searching far and near for her treasure-house, returning every few minutes to the right spot, although the upturned earth had entirely changed its appearance. She seemed unable to believe her eyes, and her persistent refusal to accept the fact that her nest had been destroyed was pathetic. She stayed about the garden all through the day, and made so many visits to us, getting under our umbrellas and thrusting her tremendous personality into our very faces, that we wondered if she were trying to question us as to the whereabouts of her property.”

Earth-digging wasps are always on the watch for

parasitic enemies. Many of them close their burrows upon leaving them even for a

short time, and some of them exercise great ingenuity in removing all traces of

their presence or in marking the spot, probably for their own assistance in

identifying it upon their return. Nor is caution unnecessary, as the parasitic

flies are often seen hunting about the neighbourhood of a wasp's excavation,

looking for the nest during the absence of the rightful owner. That wasps

carefully examine the, location of their nests, and remember the details of

their surroundings, no one can doubt who has watched them at their labours. They

do not leave a new nest until they have located it, sometimes flying back

several times to take a final look before going away. Once, while a wasp was

gone from its newly excavated nest to look for prey, a human observer, who had

been prying with great interest into the private affairs of wasp life, broke off

a large leaf that partly concealed the nest, in order to see it better. When

Madam wasp returned she was so much puzzled at the altered appearance of her

dooryard that she could not find her hole, but flew back and forth in its

vicinity, examining the surrounding objects in a state of evident excitement,

until the leaf was laid back in its old position, when she at once ran to her

nest.

Earth-digging wasps are always on the watch for

parasitic enemies. Many of them close their burrows upon leaving them even for a

short time, and some of them exercise great ingenuity in removing all traces of

their presence or in marking the spot, probably for their own assistance in

identifying it upon their return. Nor is caution unnecessary, as the parasitic

flies are often seen hunting about the neighbourhood of a wasp's excavation,

looking for the nest during the absence of the rightful owner. That wasps

carefully examine the, location of their nests, and remember the details of

their surroundings, no one can doubt who has watched them at their labours. They

do not leave a new nest until they have located it, sometimes flying back

several times to take a final look before going away. Once, while a wasp was

gone from its newly excavated nest to look for prey, a human observer, who had

been prying with great interest into the private affairs of wasp life, broke off

a large leaf that partly concealed the nest, in order to see it better. When

Madam wasp returned she was so much puzzled at the altered appearance of her

dooryard that she could not find her hole, but flew back and forth in its

vicinity, examining the surrounding objects in a state of evident excitement,

until the leaf was laid back in its old position, when she at once ran to her

nest.

The same observer once accompanied an Ammophila home through a way so intricate that the wonder was the creature ever accomplished the herculean task. This Ammophila was a little black wasp, with the usual well-developed intellect of the Ammophila folk -- for of all the wasps, they are among the most intelligent.

“During the earlier part of the summer we had

often seen these wasps feeding upon the nectar of flowers, especially upon that

of the sorrel, of which they are particularly fond, but at that time we gave

them but passing notice. One bright morning in the middle of July, however, we

came upon one that was so evidently hunting, and hunting in earnest, that we

gave up everything else to follow her. The ground was covered, more or less

thickly, with patches of purslane, and it was under these weeds that our

Ammophila was eagerly searching for her prey. After thoroughly investigating one

plant she would pass to another, running three or four steps and then bounding

as though she were made of thistledown and were too light to remain upon the

ground. We followed her easily, and as she was in full view nearly all of the

time, we had every hope of witnessing the capture, but in this we were destined

to disappointment. We had been in attendance on her for about a quarter of an

hour, when, after disappearing for a few moments under the thick purslane

leaves, she came out with a green caterpillar. We had missed the wonderful sight

of the paralyser at work, but we had no time to bemoan our loss, for she was

making off at so rapid a pace that we were well occupied in keeping up with her.

She hurried along with the same motion as before, unembarrassed by the weight of

her victim. Twice she dropped it and circled over it a moment before taking it

again. For sixty feet she kept to open ground, passing between two rows of

bushes, but at the end of this division of the garden, she plunged, very much to

our dismay, into a field of standing corn. Here we had great difficulty in

following her, since, far from keeping to her former orderly course, she

zigzagged among the plants in the most bewildering fashion, although keeping a

general direction of northeast. It seemed quite impossible that she could know

where she was going. The corn rose to a height of six feet all around us; the

ground was uniform in appearance, and, to our eyes, each group of corn-stalks

was just like every other group; and yet, without pause or hesitation, the

little creature passed quickly along, as we might through the familiar streets

of our native town.

“During the earlier part of the summer we had

often seen these wasps feeding upon the nectar of flowers, especially upon that

of the sorrel, of which they are particularly fond, but at that time we gave

them but passing notice. One bright morning in the middle of July, however, we

came upon one that was so evidently hunting, and hunting in earnest, that we

gave up everything else to follow her. The ground was covered, more or less

thickly, with patches of purslane, and it was under these weeds that our

Ammophila was eagerly searching for her prey. After thoroughly investigating one

plant she would pass to another, running three or four steps and then bounding

as though she were made of thistledown and were too light to remain upon the

ground. We followed her easily, and as she was in full view nearly all of the

time, we had every hope of witnessing the capture, but in this we were destined

to disappointment. We had been in attendance on her for about a quarter of an

hour, when, after disappearing for a few moments under the thick purslane

leaves, she came out with a green caterpillar. We had missed the wonderful sight

of the paralyser at work, but we had no time to bemoan our loss, for she was

making off at so rapid a pace that we were well occupied in keeping up with her.

She hurried along with the same motion as before, unembarrassed by the weight of

her victim. Twice she dropped it and circled over it a moment before taking it

again. For sixty feet she kept to open ground, passing between two rows of

bushes, but at the end of this division of the garden, she plunged, very much to

our dismay, into a field of standing corn. Here we had great difficulty in

following her, since, far from keeping to her former orderly course, she

zigzagged among the plants in the most bewildering fashion, although keeping a

general direction of northeast. It seemed quite impossible that she could know

where she was going. The corn rose to a height of six feet all around us; the

ground was uniform in appearance, and, to our eyes, each group of corn-stalks

was just like every other group; and yet, without pause or hesitation, the

little creature passed quickly along, as we might through the familiar streets

of our native town.

“At last she paused and laid the burden down. Ah 1 the power that has led her is not a blind, mechanically perfect instinct, for she has travelled a little too far. She must go back one row into the open space that she has already crossed, although not just at this point. Nothing like a nest is visible to us. The surface of the ground looks all alike, and it is with exclamations of wonder that we see our little guide lift two pellets of earth which have served as a covering to a small opening running down into the ground.

“The way being thus prepared, she hurries back

with her wings quivering and her whole manner betokening joyful triumph at the

completion of her task. We, in the meantime, have become as much excited

over the matter as she is herself. She picks up the caterpillar, brings it to

the mouth of the burrow and lays it down. Then, backing in herself, she catches

it in her mandibles and drags it out of sight, leaving us full of admiration and

delight.

“The way being thus prepared, she hurries back

with her wings quivering and her whole manner betokening joyful triumph at the

completion of her task. We, in the meantime, have become as much excited

over the matter as she is herself. She picks up the caterpillar, brings it to

the mouth of the burrow and lays it down. Then, backing in herself, she catches

it in her mandibles and drags it out of sight, leaving us full of admiration and

delight.

“How clear and accurate must be the observing powers of these wonderful little creatures! Every patch of ground must, for them, have its own character; a pebble here, a larger stone there, a trifling tuft of grass-these must be their landmarks. And the wonder of it is that their interest in each nest is so temporary. A burrow is dug, provisioned, and closed up, all in two or three days, and then another is made in a new place with everything to learn over again.”

That the wasp actually observes and remembers the surroundings of her nest, those just quoted proved to their cost again and again by disturbing the grass or weeds near the nest in order to see more easily, when the wasp kept them waiting endless minutes while she searched blindly about, evidently puzzled by the changes.

The wasps also noticed at once strange objects, as pebbles or seed-pods put near their nests, and one abandoned her burrow because lines had been drawn in the sand near it.

Mr. Bates tells the following story of the wasps at Santarem, illustrating their wonderful ability to find their way back to their burrows,

“While resting in the shade during the great heat of the early hours of afternoon, I used to find amusement in watching the proceedings of the sand-wasps. A small pale-green kind of Bembex was plentiful near the Bay of Mapiri. When they are at work, a number of little jets of sand are seen shooting over the surface of the sloping bank. The little miners excavate with their fore-feet, which are strongly built and furnished with a fringe of stiff bristles; they work with wonderful rapidity, and the sand thrown out beneath their bodies issues in continuous streams. They are solitary wasps, each female working on her own account.

“After making a gallery two or three inches in length, in a slanting direction from the surface, the owner backs out, and takes a few turns round the orifice, apparently to see whether it is well made, but in reality, I believe, to take note of the locality, that she may find it again. This done, the busy workwoman flies away; but returns, after an absence varying in different cases from a few minutes to an hour or more, with a fly in her grasp, with which she re-enters her mine. On again emerging, the entrance is carefully closed with sand. . . . I have said that the Bembex on leaving her mine, took note of the locality; this seemed to be the explanation of the short delay previous to her taking flight; on rising in the air, also, the insects generally flew round over the place before making straight off. Another nearly allied, but much larger species, the Monedula signata, whose habits I observed on the banks of the Upper Amazons, sometimes excavates its mines solitarily, on sand-banks recently laid bare in the middle of the river, and closes the orifice before going in search of prey. In these cases the insect has to make a journey of at least half a mile to procure the kind of fly, the Motuca, with which it provisions its cell. I often noticed it to take a few turns in the air round the place before starting; on its return it made, without hesitation, straight for the closed mouth of the mine. I was convinced that the insects noted the bearings of their nests, and the direction they took in flying from them. The proceeding in this and similar cases seems to be a mental act of the same nature as that which takes place in ourselves when recognising a locality. The senses, however, must be immeasurably more keen, and the mental operation much more certain, in them than they are in man; for to my eye there was absolutely no landmark on the even surface of sand which could serve as guide, and the borders of the forest were not nearer than half a mile. The Monedula signata is a good friend to travellers in those parts of the Amazons which are infested with the bloodthirsty Motuca. I first noticed its habit of preying on this fly one day when we landed to make our fire and dine, on the borders of the forest adjoining a sand-bank. The insect is as large as a hornet, and has a most waspish appearance.

“I was rather startled when one out of the flock which was hovering about us flew straight at my face; it had espied a Motuca on my neck, and was thus pouncing upon it. It seizes the fly, not with its mandibles, but with its fore and middle feet, and carries it off tightly held to its breast. Wherever the traveller lands in the Upper Amazons in the neighbourhood of a sand-bank, he is sure to be attended by one or more of these useful vermin-killers.”

The solitary wasps, having to search out a new

place for each cell, and being also obliged oftentimes to go far for their prey,

find it necessary to exercise both observation and memory, and that is doubtless

the reason they have become so very skilful in finding their way to a given

spot. Each nest made presents a new problem, and as long as the wasp has to

solve these problems by its own unaided skill there is little danger of its

degenerating into a mere mechanical, worker. The enforced exercise of its

faculties doubtless has been the means of developing them, and will be the means

of continuing their development.

The solitary wasps, having to search out a new

place for each cell, and being also obliged oftentimes to go far for their prey,

find it necessary to exercise both observation and memory, and that is doubtless

the reason they have become so very skilful in finding their way to a given

spot. Each nest made presents a new problem, and as long as the wasp has to

solve these problems by its own unaided skill there is little danger of its

degenerating into a mere mechanical, worker. The enforced exercise of its

faculties doubtless has been the means of developing them, and will be the means

of continuing their development.

The intelligence of the sand-wasps in closing their burrows when they leave them is certainly of a high order.

Ammophila stores her caterpillars in a pocket at the end of her rather short tunnel, and when she leaves her nest she is generally careful to close the entrance with little pellets of earth, which of course she has to remove every time she enters. Some species of Ammophila store away several small caterpillars in one nest, and at least some of them always temporarily close the nest before leaving it. Individual wasps differ in their manner of making and closing the nest, some being very particular to see that all is well done, and others extremely careless, doing their work so badly that the contents of the nest are scarcely covered from sight.

“Of two wasps that we saw close their nests on the same day, one wedged two or three pellets into the top of the hole, kicked in a little dust, and then smoothed the surface over, finishing it all within five minutes. This one seemed possessed by a spirit of hurry and bustle, and did not believe in spending time on non-essentials. The other, on the contrary, was an artist, an idealist. She worked for an hour, first filling the neck of the burrow with fine earth, which was jammed down with much energy, this part of the work being accompanied by a loud and cheerful humming, and next arranging the surface of the ground with scrupulous care, and sweeping every particle of dust to a distance. Even then she was not satisfied, but went scampering around hunting for some fitting object to crown the whole. First she tried to drag a withered leaf to the spot, but the long stem stuck in the ground and embarrassed her. Relinquishing this she ran along a branch of the plant under which she was working, and, leaning over, picked up from the ground below a good-sized stone, but the effort was too much for her and she turned a somersault on to the ground. She then started to bring a large lump of earth, but this evidently did not come up to her ideal, for she dropped it after a moment, and seizing another dry leaf, carried it successfully to the spot, and placed it directly over the nest.”

One of the most remarkable performances ever recorded of a wasp, is described by the same observers, thus, --

“Just here must be told the story of one little

wasp whose individuality stands out in our minds more distinctly than that of

any others. We remember her as the most fastidious and perfect little worker of

the whole season, so nice was she in her adaptation of means to ends, so busy

and contented in her labour of love, and so pretty in her pride over her

completed work. In filling up her nest she put her head down into it, and bit

away the loose earth from the sides, letting it fall to the bottom of the

burrow, and then, after a quantity had accumulated, jammed it down with her

head. Earth was then brought from the outside and pressed in, and then more was

bitten from the sides. When, at last, the filling was level with the ground, she

brought a quantity of fine grains of dirt to the spot, and picking up a small

pebble in her mandibles, used it as a hammer in pounding them down with rapid

strokes, thus making this spot as hard and firm as the surrounding surface.

Before we could recover from our astonishment at this performance, she had

dropped her stone and was bringing more earth.

“Just here must be told the story of one little

wasp whose individuality stands out in our minds more distinctly than that of

any others. We remember her as the most fastidious and perfect little worker of

the whole season, so nice was she in her adaptation of means to ends, so busy

and contented in her labour of love, and so pretty in her pride over her

completed work. In filling up her nest she put her head down into it, and bit

away the loose earth from the sides, letting it fall to the bottom of the

burrow, and then, after a quantity had accumulated, jammed it down with her

head. Earth was then brought from the outside and pressed in, and then more was

bitten from the sides. When, at last, the filling was level with the ground, she

brought a quantity of fine grains of dirt to the spot, and picking up a small

pebble in her mandibles, used it as a hammer in pounding them down with rapid

strokes, thus making this spot as hard and firm as the surrounding surface.

Before we could recover from our astonishment at this performance, she had

dropped her stone and was bringing more earth.

We then threw ourselves down on the ground that not a motion might be lost, and in a moment we saw her pick up the pebble, and again pound the earth into place with it, hammering now here and now there, until all was level. Once more the whole process was repeated, and then the little creature, all unconscious of the commotion that she had aroused in our minds, unconscious, indeed, of our very existence, and intent only on doing her work and doing it well, gave one final comprehensive glance around and flew away.”

This remarkable occurrence is not the only one of the kind on record, for in Western Kansas a species of Ammophila was observed to use a pebble in the same way to close the opening to her hole. The facts are thus reported, --

“When the excavation had been carried to the required depth, the wasp, after a survey of the premises, flying away, soon returned with a large pebble in its mandibles, which it carefully deposited within the opening; then, standing over the entrance upon her four posterior feet, she (I say she, for it was evident that they were all females) rapidly and most amusingly scraped the dust with her two front feet, 'hand over hand,' back beneath her, till she had filled the hole above the stone to the top. The operation so far was remarkable enough, but the next procedure was more so. When she had heaped up the dirt to her satisfaction, she again flew away, and immediately returned with a smaller pebble, perhaps an eighth of an inch in diameter, and then, standing more nearly erect, with the front feet folded beneath her, she pressed down the dust all over and about the opening, smoothing off the surface, and accompanying the action with a peculiar rasping sound. After all this was done, and she spent several minutes each time in thus stamping the earth, so that only a keen eye could detect any abrasion of the surface, she laid aside the little pebble and flew away, to be gone some minutes.

“Upon her return she bore a large green larva, and laying it down near the door, she opened her carefully closed burrow, dragged in her prize and sealed it up as carefully as before, again using the little pebble to pound down the surface. This laborious operation was repeated several times until the requisite number of larvae had been stored. Once the observer varied the routine by taking away the little pebble that closed the door, while the wasp was in her hole. Returning, she looked about for her door, but not finding it, apparently mistrusted the honesty of a neighbour, which had just descended, leaving her own door temptingly near. She purloined this pebble and was making off with it, when the rightful owner appeared and gave chase, compelling her to relinquish it.”

There is another very remarkable story of an

Ammophila, told by Mr. Theodore Pergande to the Entomological Society of

Washington. While on a gravelly slope Mr. Pergande noticed a female sand-wasp,

belonging to the genus Ammophila, flying about in a peculiar fashion. Presently

it alighted and ran briskly about in every direction, with the head close to the

ground and the abdomen elevated, while the antennae were in constant agitation,

as if searching for something important, though nothing in any-way striking to

the eye could be seen on the bare sand which could have attracted its attention.

Suddenly it stopped at a certain spot, pressed the head close to the ground, and

commenced beating the ground with its abdomen, producing at the same time a

quite sharp sound similar to bss, bss, bss, tapping with each sound the earth

with its abdomen. It continued this performance for some time, running or flying

off a short distance twice or thrice during brief intervals. Finally it picked

up with its jaws “a small pebble, carried it to the mysterious spot, and

deposited it on top, pressing the pebble down as much as possible to insure its

remaining in-position. Running then again a distance away, it picked up another

pebble and placed it close to the first one; after a while a third was added. No

more pebbles of the desired size being near enough at hand, it ran some distance

farther, when it came across a pebble which appeared to suit its purpose; took

hold and lifted it, but unfortunately the shape of this little stone was such

that it slipped from its jaws. It tried again and again for quite a while to

obtain a good hold, though without success, when it left it in apparent disgust.

Running about after this failure for some time, in search of a more suitable

stone, but not finding what was wanted, she returned to her little monument of

pebbles and commenced to rearrange them and press them down as much as possible.

After being satisfied that everything was well done, she flew away, not to

return.” After she had gone Mr. Pergande removed the little stones and dug out

her caterpillar, with the egg attached.

There is another very remarkable story of an

Ammophila, told by Mr. Theodore Pergande to the Entomological Society of

Washington. While on a gravelly slope Mr. Pergande noticed a female sand-wasp,

belonging to the genus Ammophila, flying about in a peculiar fashion. Presently

it alighted and ran briskly about in every direction, with the head close to the

ground and the abdomen elevated, while the antennae were in constant agitation,

as if searching for something important, though nothing in any-way striking to

the eye could be seen on the bare sand which could have attracted its attention.

Suddenly it stopped at a certain spot, pressed the head close to the ground, and

commenced beating the ground with its abdomen, producing at the same time a

quite sharp sound similar to bss, bss, bss, tapping with each sound the earth

with its abdomen. It continued this performance for some time, running or flying

off a short distance twice or thrice during brief intervals. Finally it picked

up with its jaws “a small pebble, carried it to the mysterious spot, and

deposited it on top, pressing the pebble down as much as possible to insure its

remaining in-position. Running then again a distance away, it picked up another

pebble and placed it close to the first one; after a while a third was added. No

more pebbles of the desired size being near enough at hand, it ran some distance

farther, when it came across a pebble which appeared to suit its purpose; took

hold and lifted it, but unfortunately the shape of this little stone was such

that it slipped from its jaws. It tried again and again for quite a while to

obtain a good hold, though without success, when it left it in apparent disgust.

Running about after this failure for some time, in search of a more suitable

stone, but not finding what was wanted, she returned to her little monument of

pebbles and commenced to rearrange them and press them down as much as possible.

After being satisfied that everything was well done, she flew away, not to

return.” After she had gone Mr. Pergande removed the little stones and dug out

her caterpillar, with the egg attached.

Evidently this wasp had found the exact location

of her nest by listening to the sounds made by striking the abdomen against the

ground and buzzing at the same moment.

Evidently this wasp had found the exact location

of her nest by listening to the sounds made by striking the abdomen against the

ground and buzzing at the same moment.

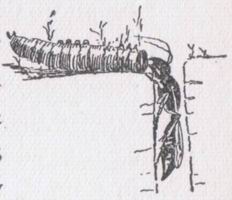

The Ammophila finds in paralysing her caterpillars a more difficult problem than faces those wasps that use the adult insect as provision for their young. A well-directed sting in the central nerve-ganglion of an adult insect is enough to paralyse, or even to kill it, but the caterpillar, being a larva and composed of a number of segments, each with its own nerve centre, requires more heroic treatment, and this, Ammophila well knows. She catches her caterpillar and stings it, not once, but several times, each time in or near a different nerve-centre. Her performance in poisoning her prey has been thus described by an eye-witness, --

“Standing high on her long legs and disregarding the continued struggles of her victim, she lifted it from the ground, curved the end of her abdomen under its body, and darted her sting between the third and fourth segments. From this instant there was a complete cessation of movement on the part of the unfortunate caterpillar. Limp and helpless, it could offer no further opposition to the will of its conqueror. For some moments the wasp remained motionless, and then, withdrawing her sting, she plunged it successively between the third and the second, and between the second and the first segments.

“The caterpillar was now left lying on the

ground. For a moment the wasp circled above it and then seized it again, further

back this time, and with great deliberation and nicety of action gave it four

more stings, beginning between the ninth and tenth segments and progressing

backward.”

“The caterpillar was now left lying on the

ground. For a moment the wasp circled above it and then seized it again, further

back this time, and with great deliberation and nicety of action gave it four

more stings, beginning between the ninth and tenth segments and progressing

backward.”

This order of proceeding is not by any means invariable with the wasps; some sting but two or three times; some sting nearly all the segments. The number of stings applied and the order in which they are given depend upon the individual wasp. They all understand in a general way the advisability of stinging a caterpillar more than once, but beyond this they exercise their own judgment.

While the miners generally live quite apart from each other, some species congregate together in colonies, as do certain species of the solitary bees; where this is the case it is quite an experience to come upon the broad, bare spot usually selected by these fierce-looking settlers. Each wasp has her own hole, which she locates accurately and finds immediately after an absence; she does not stumble into her neighbour's nursery, and probably would meet a very bad reception if she did. These wasps must possess quite enviable powers of observation, as well as very reliable memories, to enable them to come flying rapidly from a distance and drop upon just the right spot in a bank where, to the human eye, there is nothing to mark the place, and where all about are other concealed burrows of neighbours, ready to pounce upon the luckless householder who should make a mistake and attempt to open the wrong door. Although the wasps live thus in settlements, they are no more free from petty disagreements with their neighbours than are much larger and supposedly wiser creatures.

Sometimes they quarrel, and apparently for the mere sake of quarrelling, very likely finding in this interesting pastime an outlet for overflowing wasp spirits. Sometimes they do more than quarrel; they are mean enough to steal one another's provisions when hunting is poor; and when one returns with a prize, several will give chase and try to relieve her of her burden.

Certain of the fossorial wasps, when they bring

prey to the burrow, first enter to see that all is as they left it, leaving the

captured insect near the entrance. If the result of their examination is

favourable, out comes the wasp and drags in the insect. Once a French naturalist

removed the cricket one of these wasps had captured and placed close to the

entrance to her hole while she went in to reconnoitre. It was placed several

inches away, but was shortly found by the wasp and dragged back to the hole.

Again her ladyship went in to reconnoitre and again the cricket was taken away:

It was found as before and dragged back, while the wasp, true to her habit, went

in the hole and left it at the entrance. The same thing was repeated over forty

times, until the patience of the experimenter gave out; and one can imagine the

nervous condition of the wasp at this unaccountable and persistent interference

with a matter that from her point of view was nobody's business but her own. Had

it occurred to Madam to look for troublesome intruders outside the hole instead

of inside, she would have saved herself a great deal of time and strength.

Certain of the fossorial wasps, when they bring

prey to the burrow, first enter to see that all is as they left it, leaving the

captured insect near the entrance. If the result of their examination is

favourable, out comes the wasp and drags in the insect. Once a French naturalist

removed the cricket one of these wasps had captured and placed close to the

entrance to her hole while she went in to reconnoitre. It was placed several

inches away, but was shortly found by the wasp and dragged back to the hole.

Again her ladyship went in to reconnoitre and again the cricket was taken away:

It was found as before and dragged back, while the wasp, true to her habit, went

in the hole and left it at the entrance. The same thing was repeated over forty

times, until the patience of the experimenter gave out; and one can imagine the

nervous condition of the wasp at this unaccountable and persistent interference

with a matter that from her point of view was nobody's business but her own. Had

it occurred to Madam to look for troublesome intruders outside the hole instead

of inside, she would have saved herself a great deal of time and strength.

That wasps may exercise ingenuity in capturing their prey is proved by the following story.

A wasp was once seen to alight within an inch or two of a spider's nest on the side opposite the opening.

“Creeping noiselessly around towards the entrance of the nest, the wasp stopped a little short of it and for a moment remained perfectly quiet, then reaching out one of his antennae he wriggled it before the opening and withdrew it. This overture had the desired effect, for the boss of the nest, as large a spider as one ordinarily sees, came out to see what was wrong and to set it to rights. No sooner had the spider emerged to that point at which he was at the worst disadvantage, than the wasp, with a quick movement, thrust his sting into the body of his foe, killing him easily and almost instantly. The experiment was repeated on the part of the wasp, and when there was no response from the inside, he became satisfied, probably, that he held the fort.

“At all events he proceeded to enter the nest and slaughter the young spiders, which were afterwards lugged off one at a time.”

Another wasp tried a similar experiment on a

caterpillar rolled in a leaf. The wasp examined both ends of the rolled leaf

only to find them closed. It then clipped a hole in one end. Having done this,

it went to the other end and made a noise which frightened the caterpillar and

caused it to rush out of the hole the wasp had cut. Of course the wise wasp

seized the foolish caterpillar, stung it, and attempted to carry it home.

Finding it too large, her waspship cut it in two, carried away one half, and

came back for the rest.

Another wasp tried a similar experiment on a

caterpillar rolled in a leaf. The wasp examined both ends of the rolled leaf

only to find them closed. It then clipped a hole in one end. Having done this,

it went to the other end and made a noise which frightened the caterpillar and

caused it to rush out of the hole the wasp had cut. Of course the wise wasp

seized the foolish caterpillar, stung it, and attempted to carry it home.

Finding it too large, her waspship cut it in two, carried away one half, and

came back for the rest.

Another wasp was once watched trailing a spider that tried to escape by running into a room and hiding. When the quarry disappeared the wasp ran in narrowing' circles like a hound, and when it struck the scent it followed all the turns the spider had made, just as a dog would have done.

The wasp finally captured the spider, and tucking it up under its long hind-legs, just as a hawk carries off its quarry, flew away with it.

A few species of wasps catch their prey first and then dig the burrow. Among these is a pretty little black and white creature that rears her progeny upon spiders. She catches her spider and to save it from the ants that are always lurking about, she sometimes hangs it up in a plant while she digs her burrow. She does not always do this, and whether this very intelligent act depends upon the prevalence of ants in the neighbourhood, acting upon a superior intellectual development of the individual wasp that does it, who shall say ?

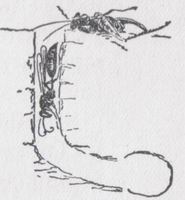

One of these wasps once dug her nest and caught

her spider -- a large one, which she dragged near her burrow. “Presently she

went to look at her nest and seemed to be struck with a thought that had already

occurred to us, -- that it was decidedly too small to hold the spider. Back she

went for another survey of her bulky victim, measured it with her eye, without

touching it, drew her conclusions, and at once returned to the nest and began to

make it larger. We had several times seen wasps enlarge their holes when a trial

had demonstrated that the spider would not go in, but this seemed a remarkably

intelligent use of the comparative faculty. . . . While she was thus employed,

the spider was attacked by a very tiny red ant, that could not by any

possibility have stirred it. When the wasp caught sight of this insignificant

marauder she fell into a fit of wild fury, and bending her abdomen under, seized

the ant again and again in her mandibles, and flung it backward against the tip

of her sting. The little creature finally escaped, seeming none the worse for

the rough handling to which it had been subjected, while the wasp, still

trembling with excitement, grasped her spider and rushed off to a distance of

several feet, carrying it up on a weed and depositing it there. The labour of

excavation was then resumed, and after half an hour's work, was completed to her

satisfaction. Coming up head first, she flattened herself out on the ground, and

sprawling thus, dragged herself all around it. The spider was now brought to the

nest, being left once on the way, while she ran in and out again, and was taken

in after a new and original fashion. Backing in herself, she seized it by the

tip of the abdomen1 and dragged it down without any trouble, since

the legs were gently pushed up over the head and made no resistance.

One of these wasps once dug her nest and caught

her spider -- a large one, which she dragged near her burrow. “Presently she

went to look at her nest and seemed to be struck with a thought that had already

occurred to us, -- that it was decidedly too small to hold the spider. Back she

went for another survey of her bulky victim, measured it with her eye, without

touching it, drew her conclusions, and at once returned to the nest and began to

make it larger. We had several times seen wasps enlarge their holes when a trial

had demonstrated that the spider would not go in, but this seemed a remarkably

intelligent use of the comparative faculty. . . . While she was thus employed,

the spider was attacked by a very tiny red ant, that could not by any

possibility have stirred it. When the wasp caught sight of this insignificant

marauder she fell into a fit of wild fury, and bending her abdomen under, seized

the ant again and again in her mandibles, and flung it backward against the tip

of her sting. The little creature finally escaped, seeming none the worse for

the rough handling to which it had been subjected, while the wasp, still

trembling with excitement, grasped her spider and rushed off to a distance of

several feet, carrying it up on a weed and depositing it there. The labour of

excavation was then resumed, and after half an hour's work, was completed to her

satisfaction. Coming up head first, she flattened herself out on the ground, and

sprawling thus, dragged herself all around it. The spider was now brought to the

nest, being left once on the way, while she ran in and out again, and was taken

in after a new and original fashion. Backing in herself, she seized it by the

tip of the abdomen1 and dragged it down without any trouble, since

the legs were gently pushed up over the head and made no resistance.

“In two minutes she emerged from the opening, and standing on the four posterior legs, with her abdomen hanging down into the hole, scratched the earth backward with the front legs and mandibles. As it fell in she pushed it down with the abdomen, and as the hole filled she raised herself higher and higher on her legs, still using the tip of the abdomen to work the material into place.”

The underground nests of the digger-wasps differ in form according to the species, and somewhat according to the individual. They all make a burrow, however, ending in some sort of little compartment, where the insects used as food can be stored. Many of them store but one large insect in a burrow. Many others store a number of smaller insects, for the nourishment of each larva. A few build little pockets or rooms from the side of the main burrow, thus constructing a house of several rooms, instead of making a separate burrow for each egg laid.

Each species has its favourite insect, some catching spiders, some caterpillars, some beetles, some bugs, some aphides, and so on.

Some species prefer bees, catching two dozen or more wild bees to store one nest; and there are wasps in the world that prefer honey-bees to anything else, these sometimes causing havoc among the hives.

While some wasps sting their prey to paralysis, others injure the, captured insects very little, and still others sting them to death. Some, again, do not sting the insect at all, but bite it until it is quiet, often squeezing the neck with the mandibles without otherwise injuring the insect. The object of stinging seems to have been, in the beginning, to render the insect quiet, and from this starting-point we find all degrees of completeness in paralysing the food among the different species.

While most of the earth-boring species provision the nest once for all and close it up, we find some that put in only what food the larva requires at the time, and from day to day open the nest and replenish the store. These care for the young after the manner of the social wasps, but without the conveniences of the communal society composed largely of workers. They seem to exist in an intermediate stage between the social wasps and the perfected diggers.

The fossorial wasps, having no home to which to retire, as the paper-makers have, are possessed of a more roving disposition, and are particularly fond of flying about in the warm sunshine. Many of them have long tongues, similar in structure to the tongue of the hornet, but with all the parts so elongated that the wasp can reach almost as far as a honey-bee into a flower cup.

They hide away at night and during stormy

weather in sheltered crevices, and some of them dig holes in the ground, not for

the benefit of their progeny, but to provide a lodging for themselves. In some

instances the little male builds himself a tunnel, into which to retire when he

wishes to rest.

They hide away at night and during stormy

weather in sheltered crevices, and some of them dig holes in the ground, not for

the benefit of their progeny, but to provide a lodging for themselves. In some

instances the little male builds himself a tunnel, into which to retire when he

wishes to rest.

When the boneset is in bloom in late summer, numbers of the large wasps may be seen at work among its white heads. But it is when the goldenrod comes into blossom that the wasp collector and the wasp observer find their veritable land of delight. All sorts of bees and wasps flock to the goldenrods, as do also the butterflies, which seem to take a mischievous delight in tormenting the wasps.

Time and again when a wasp rises from a flower a butterfly will also rise and flutter its wings about the distracted wasp, which tries to dodge this way and that to escape its tormentor.

One can almost see the wasp get out of temper, and the frivolous butterfly laugh at it. But getting out of temper with a butterfly is wasted energy; the broad, thin wings are unstingable; and indeed the wasp does not try to sting, but only to dodge away from the mischievous and no doubt heartily despised trifler.

The butterfly can have no possible object in interfering with the wasp other than the mere fun of it, and one is glad to discover that butterflies possess, like ourselves, a sense of humour.

In watching wasps one cannot fail to make the

intimate acquaintance of many other tribes of insects, and the dramas, absurd or

tragic, always enacting in the air about us or on the ground under our feet,

must be witnessed to be appreciated.

In watching wasps one cannot fail to make the

intimate acquaintance of many other tribes of insects, and the dramas, absurd or

tragic, always enacting in the air about us or on the ground under our feet,

must be witnessed to be appreciated.

Insects, like other animals, seem not to be devoid of curiosity. One day a small green katydid intently observing the sand coming out of a hole where a small black Sphex was digging away for dear life, went and looked in when the wasp retired with a load of earth, upon which the wasp became greatly excited and fell upon that katydid and chased him away. Once more the too curious katydid walked toward the hole, but he did not look in this time, for the wasp, with quivering wings and angry buzzing, ran after him and he scampered off not to return, evidently concluding that discretion was preferable to gratified curiosity under the circumstances.

Many of the fossorial wasps are very suspicious, and it requires patience to get near enough to watch one at its work of nectar-gathering. It cocks its head on one side, glances at the intruder, and in a flash is off.

Sometimes, however, the large wasps resent

intrusion, as one once did on the edge of a meadow. It was sitting on a willow

leaf and did not care to be disturbed. Instead of flying away it reared itself

up on its tail, opened its jaws and apparently invited its visitor to “touch me

if you dare.” Its visitor did not dare, having no net along; and probably nobody

would have enjoyed interfering with an enormous black wasp that reared up on end

and looked as that one did.

Sometimes, however, the large wasps resent

intrusion, as one once did on the edge of a meadow. It was sitting on a willow

leaf and did not care to be disturbed. Instead of flying away it reared itself

up on its tail, opened its jaws and apparently invited its visitor to “touch me

if you dare.” Its visitor did not dare, having no net along; and probably nobody

would have enjoyed interfering with an enormous black wasp that reared up on end

and looked as that one did.

Wasps dig many holes, but finish few. They seem to have very strict ideas as to what a burrow should be, and often start half a dozen before the earth is just right to their critical judgment.

One watching the many fruitless attempts of the countless numbers of wasps winging their way over the earth in the latter part of the summer cannot but imagine the value of these little earth-openers to the soil. Their countless unfinished burrows in the hard earth, as well as their finished ones, let in air and water; the water settles to still deeper parts, and later freezing breaks up the hardened soil to an extent out of all proportion to the work of the little digger. No doubt to the wasp we owe in part the fertility of the face of the earth.

Although at times such hard workers, wasps appear to waste a great deal of time fussing about.

Small black Sphex wasps were often watched flying along the carriage road up and down, up and down, alighting every moment and running along as though they had lost something they needed very badly but could not find.

They were doubtless looking for places suitable

to dig in, but to the observer ignorant of the nicer distinctions of wasp

problems, they seemed to be very lightheaded and to be wasting a great deal of

time. When one had begun to dig its hole it was easily frightened away by a

passer-by, and when it returned employed somewhat the tactics of the partridge

when trying to conceal its young. It did not go straight to its hole, but ran a

long way past it on one side and then on the other and hunted about as if it had

never started a hole in the world. Then, all at once, perhaps believing it had

thrown any possible observer quite off the track, it popped into its hole and

went to work vigorously continuing the excavation. There are some species of

the digger-wasps that make their excavations in bricks or in sand-banks that are

almost as hard as stone. These little miners are as careful as the wood-borers

not to leave chips lying about to betray their presence to the enemy. They dig

out the hard brick or sand with their jaws, moistening and softening it with

liquid from their mouths, and as soon as they have chiselled out a fragment they

fly to some distance and drop it. They do not go in very far, usually not more

than two inches. Sometimes they line with clay the cave they have excavated, and

stop the opening also with clay.

They were doubtless looking for places suitable

to dig in, but to the observer ignorant of the nicer distinctions of wasp

problems, they seemed to be very lightheaded and to be wasting a great deal of

time. When one had begun to dig its hole it was easily frightened away by a

passer-by, and when it returned employed somewhat the tactics of the partridge

when trying to conceal its young. It did not go straight to its hole, but ran a

long way past it on one side and then on the other and hunted about as if it had

never started a hole in the world. Then, all at once, perhaps believing it had

thrown any possible observer quite off the track, it popped into its hole and

went to work vigorously continuing the excavation. There are some species of

the digger-wasps that make their excavations in bricks or in sand-banks that are

almost as hard as stone. These little miners are as careful as the wood-borers

not to leave chips lying about to betray their presence to the enemy. They dig

out the hard brick or sand with their jaws, moistening and softening it with

liquid from their mouths, and as soon as they have chiselled out a fragment they

fly to some distance and drop it. They do not go in very far, usually not more

than two inches. Sometimes they line with clay the cave they have excavated, and

stop the opening also with clay.

There is a little miner-wasp in Europe that uses the material it removes from its burrow in a hard sand-bank to make a round tower over its hole. The French naturalist Réaumur watched these wasps at work easily cutting into a sand-bank that was almost as hard as stone. Having detached a few grains of sand, the wasp kneads it into a pellet with liquid from its mouth, and this pellet is attached at the mouth of the excavation. The wasp forms another pellet, adds it to the first, and continues in this way until it has constructed a little chimney or tower over its hole. The tower is not a good piece of masonry, however, as the pellets are not carefully joined, but openings are often left between them. Although the tower at first is built perpendicular to the wall upon which it rests, at the outer end it is curved to correspond to the curve of the insect's body. This makes the tower easy of entrance to the rightful occupant, but would exclude a larger enemy. When the little nest is finished, provisioned, occupied, and sealed, the tower, which it seems was only a temporary structure is taken down as expeditiously as it was put up.

There have been various guesses as to why this tower is built by the wasp (Odynerus murarius). Is it to protect the young larva from the heat of the sun? Is it to keep out the parasitic flies that naturally would be discouraged from entering into any such deep, dangerous tunnel?

Man may question, but Odynerus does not reply. While he speculates upon her object in doing so she continues to build her mysterious towers before his eyes quite indifferent to his presence or his curiosity.

One sometimes sees a brilliant scarlet and black insect, wingless, ant-like in form, but clothed with a thick velvety coat, hastening along a path or a roadside.

One's first impulse is to catch it, but second thoughts in this case are decidedly the best; for this gorgeous “velvet ant,” as it is called, is not an ant at all, but a wasp. Although it is so unwasp-like as to have no wings, it retains its sting without diminution, as whoever attempts to pick it up will quickly discover. The males are winged and are sometimes seen about flowers, but the females have given up the vanity of wings and remain on the earth, where they can run very fast and where they dig burrows and store up insects for their progeny. There are a great many species of the velvet ant, and some of them are found in the nests of bumble-bees and of other wasps. The Texans call the velvet ant the Cow-killer ant, and believe that its sting is dangerous to cattle.

Most of the solitary wasps are remarkable for

their unflagging industry. Each excavation in brick or wood or earth may take

several days to complete; it must then be provisioned and sealed, and no sooner

is this done than the faithful little mother begins another. Half a dozen or

more of these cradle-cells, with provisions and infant wasp occupants, testify

to her industry.

Most of the solitary wasps are remarkable for

their unflagging industry. Each excavation in brick or wood or earth may take

several days to complete; it must then be provisioned and sealed, and no sooner

is this done than the faithful little mother begins another. Half a dozen or

more of these cradle-cells, with provisions and infant wasp occupants, testify

to her industry.

Late in the season, however, the wasps have a grand rally, an enormous picnic, where the chief occupations are sitting in the sun, drinking nectar from the autumn flowers, flying swiftly about in the noonday heat, and getting into the houses, to the consternation of the human occupants, who, though much larger and stronger than wasps, are nevertheless very much afraid of them.

Then can they be caught by the score in the skilfully wielded net of the insect collector. Big wasps, little wasps, black, red, yellow, blue, white, all colours, shapes, and sizes, they may be gathered in. Then, too, the young male wasps are as abundant as the females, both frequenting the goldenrods when the sun is bright.

They have their good time drinking nectar and eating insects if they feel so inclined. Then, too, come the yellow-jackets and hornets to swell the numbers.

That wasps are capable of enjoying themselves, no one can doubt who has watched them at this time of year.

Once a hornet was watched in holiday mood, eating a fly while hanging by one foot to a twig.

“The half-eaten fly was held by the front feet, while the other legs and the wings stuck out carelessly in all directions. As the mandibles or jaws and the antennae kept in rapid motion, and the fly was turned over and over by the fore-feet, the wasp swung slowly back and forth with the same appearance of enjoyment and comfort as a man eating an apple in a hammock.”

Nor has the solitary wasp been wholly neglected by the ancients; with them it too had its use, for Moffett says, --

“Pliny greatly commendeth the solitary Wasp to be very effectual against a Quartain Ague, if you catch her with your left hand, and tie or fasten her to any part of your body (always provided that it must be the first Wasp that you lay hold on that year).”

There are a number of curious and interesting little creatures called gall-wasps, which belong to the Order Hymenoptera, but not to the wasp division.

The so-called Fig-wasp with its remarkable habit of fertilising figs, is not a wasp, but belongs rather among the gall-insects, which are boring, instead of stinging, Hymenoptera.

No doubt the solitary wasps play their part in fertilising the flowers, and are valued and necessary agents.

It should not be forgotten that the wasps, through their habit of using insects to feed their young, are exceedingly valuable; to the agriculturist. From a single nest have been taken several dozens of canker worms, and even where but few insects are stored in a burrow, the immense number of wasps using them acts as a check to the insect pests. Aphides, caterpillars, beetles, bugs, numberless destructive creatures are laid to rest in the nests of the wasps.

The wasp has its place in the scheme of the world, and but for it the hordes of insects destructive to vegetation might lay waste the gardens of the earth, even to the discomfiture of proud man himself.

Then all honour to the little wasps, whose influence in human society may in its own sphere be as important and as far reaching as that of more powerful-seeming forces.

All honour to the little wasps, who, a link in the endless chain of living things, are doing their work and helping to make possible that higher civilisation which man fondly believes belongs to himself alone.

__________________

1

Wasps generally drag their victims down head first.

THE END