|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

IV

THE COMMON AND ROUND ABOUT

“For their domestic amusement, every afternoon after drinking tea, the gentlemen and ladies walk the Mall and from thence adjourn to one another’s houses to spend the evening — those that are not disposed to attend the evening lecture, which they may do, if they please, six nights in seven the year round. What they call the Mall is a walk on a fine green Common adjoining to the southwest side of the Town. It is near half a mile over, with two rows of young trees planted opposite to each other, with a fine footway between in imitation of St. James’s Park; and part of the bay of the sea which encircles the Town, taking its course along the northwest side of the Common — by which it is bounded on the one side, and by the country on the other — forms a beautiful canal in view of the walk.”

This dainty picture of the early eighteenth-century Common, and the earliest picture we have of Boston Common in any detail, was recalled as we three sauntered on to the beautiful preserve of to-day of nearly fifty acres in the heart of the city, entering from the busy Tremont and Park streets corner amidst the throngs in continuous passage to and from the Subway stations. It is the Englishman Bennett’s picture, our English visitor was told, of Boston Common as he saw it, presumably about the year 1740. The Mall he portrays so engagingly as the Town’s social promenade, is the Mall alongside Tremont Street. When Bennett wrote, this was the only Mall, as it had been in Colony days, when the visiting Josselyn pictured the rustics with their “marmalet-madams” perambulating the Common of evenings “till the Nine a Clock Bell rings them home to their respective habitations”; and it remained the only one till after the Revolution. West of it the whole reserve was used as the military training field and pasturage for cattle, for which it was originally set apart at the beginning of Boston. Or, as is recorded on the handsomely framed tablet we observe against the Park Street fence at the entrance, with the purchase of the whole peninsula in 1634, save his home-lot of six acres on Beacon Hill, from the hospitable Englishman, Blaxton, in comfortable possession here when the colonists arrived.

The Mall in Bennett’s time, with its double row of young elms, was finished off with a few sycamores at the northerly end and poplars at the southerly end, all set out only a few years before. Beyond these, save one solitary elm in the middle of the Common, and a great one, — for there are legends of the hanging of witches, if not of Quakers, from its rugged branches, — the reserve was treeless; and it remained practically so through the Province period. A picture of the date of 1768 shows the “Great Elm” and a lonely sapling far out in the open. Until a few years before Bennett saw it, the Common had no fences. The front fences, set up in 1733-1734, and 1737, were railings along the easterly and northerly sides. These were the fences that the British soldiers encamped on the Common used for their campfires during the Siege; the trees were saved from destruction by Howe’s orders, at the earnest solicitation of the selectmen, and especially of John Andrews, who lived near by, an act for which the Bostonians were, or should have been, grateful. An inner fence, parallel with the inner row of elms, protected the Mall from the grazing field. From the outset the trees on the Mall were carefully guarded by the townsfolk, and orders were occasionally passed in Town meeting whipping up the selectmen to protect individual trees when threatened. The year that the inner row on the Mall was planted, 1734, a Town meeting order offered a reward of forty shillings to the informer against any persons guilty of cutting down or despoiling any tree then here or that might be planted in the future. The protection of the Common from injury or abuse was a matter of concern in the earliest times. Orders appeared in the sixteen fifties against “annoying” the Common by spreading “trash”, or laying any carrion or other “stinkeing thing” upon it. Thus we see a wholesome solicitude for the Common, and a lively sense of its value is an inheritance from Old Boston. Yet it barely escaped ruin more than once in old days. In its very first year an attempt to have it divided up in allotments was only frustrated through the action of Governor Winthrop and John Cotton. After the Revolution, the disposal of a considerable part of it to be cut up into lots was checked by the personal exertion of that John Andrews who saved the trees during the Siege.

The fence of 1734 on the easterly side was at first provided with openings opposite the streets and lanes entering Tremont — then Common — Street, “Blott’s Lane”, our Winter Street, West Street, and “Hogg Lane”, Avery Street. Very soon, however, these openings were closed up by a Town meeting order, because the Common had become “much broken and the herbage spoiled by means of carts &c. passing and repassing over it,” and a single entrance for “carts, coaches, &c.” out of Common Street, provided at the northerly side where is Park Street. After the Revolution, in 1784, when great improvements in various parts of the Common were begun, at the cost of a fund subscribed by generous townsmen for the purpose, the fences were restored, and a third row of elms was planted on this Mall. But the larger improvements, the laying out of other malls and of cross paths, and systematic tree-planting in the open, giving the enclosure a more general park aspect, were all after the second decade of the nineteenth century. The spacious Beacon Street Mall was the first of the new esplanades, laid out in 1815—1816; and the magnificent breadth and sweep of it, greatly to the credit of the broad-visioned designers and their artistic sense, was the model for the others that followed. When told that the Beacon Street Mall was paid for from a subscription raised in 1814 for the purpose of providing for the defense of Boston against a contemplated English attack, which wasn’t made, in the War of 1812, our Englishman observed, with a twinkle of eye, that it was a much finer disposition of the money. The Park Street and the Charles Street Malls followed in 1822—1824, the first Mayor Quincy’s time; and the Boylston Street Mall in 1836, thus completing the encircling of the Common by malls. At that time the iron fence was placed, and parts of it still remain on three sides. The handsome gates forming part of this extensive structure long ago disappeared, to the sorrow of many citizens. The handsome Boylston Street Mall was destroyed by the building of the Subway in the eighteen nineties. The Tremont Street Mall was also sadly despoiled at the, same time, magnificent English elms falling under the axe, to mournful dirges of hosts of Bostonians. And after the completion of the Subway beneath it, sapient city authorities bereft the Mall of its old distinctive name of Tremont Street, and, in a burst of belated patriotism, substituted that of Lafayette; because, forsooth, that well-beloved Frenchman passed by the Mall along Tremont Street with the escorting procession, upon his memorable visit in 1824.

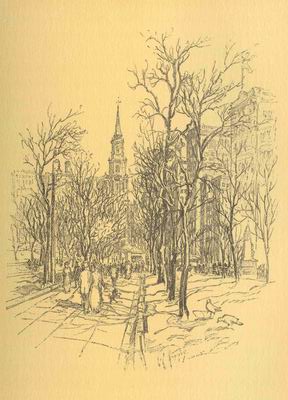

On the Common, showing Park Street Church

The integrity of the Common rests first, on the order of the Town, March 30, 1640, declaring that “henceforth” no land within the reservation as then defined be granted “eyther for houseplotts or garden to any pson”; second, on an order of May 18, 1646, prohibiting the gift, sale, or exchange of any “common marish or Pastur Ground” without consent of “ye major p’ of y. inhabitants of ye towne”: thus preserving the power of control of the Common with the legal voters; and, third, on a section of the city charter reserving the Common and Faneuil Hall from lease or sale by the city council, in whose hands the care, custody, and arrangement of the city’s property were placed. The title is in the deposition of the four “ancient men”, in 1684, the essence of which is the inscription on the tablet at the Park Street entrance. In the absence of a recorded title, if any were given by Blaxton, this deposition was obtained after the annulment of the Colony Charter, when the proprietors under that instrument were threatened with loss of their estates, on the pretext that their grants had not passed under the charter seal. The four “ancient men” were among the last survivors of the first comers. The Common’s bounds originally extended on the easterly side across the present Tremont Street to Mason Street, opening from West Street; and northward as far as Beacon Street, including the square now bounded by Park, Tremont and Beacon streets. Thus it is seen the Granary Burying-ground and Park Street were taken from it.

So much for the topographical history of the Common. While we were dutifully outlining this history, the Englishman was absorbing the exquisite vistas from Park Street Church up Tremont Street and the Mall; and from the meeting-house up Park Street to the noble old Bulfinch front of the State House. Then he turned toward the meeting-house itself — the “perfectly felicitous Park Street Church,” as Henry James calls it — and admired the beauty of its site as the focal center of rich city vistas, and its “values” as an architectural monument, the grace of its composition, its crowning feature of tower and tall, slender, graceful steeple recalling Wren’s St. Bride’s, Fleet Street.

While this church is less a monument of Old Boston than the Old South, King’s Chapel, and Christ Church, it is classed with the historic group because of its associations, as remarkable in their way as those of the others, and on account of its character as one of the finest types of the few remaining examples of the colonial church architecture. It dates from 1809—1810, erected for the church founded in 1808 to revive Trinitarianism, and directly to combat the Unitarian invasion which, starting with the establishment of King’s Chapel, after the Revolution, as the first Unitarian church in America, had overwhelmed all the Orthodox churches in Boston except the Old South. Channing was then preaching in the Federal Street Church; William Emerson, the father of Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the First Church; John Lathrop in the Second Church; Charles Lowell, James Russell Lowell’s father, in the West Church; John Thornton Kirkland in the New South, to go from that pulpit in 1810 to the presidency of Harvard; while in 1805 Henry Ware, Sr., a pronounced Unitarian, had been duly made Hollis Professor of Divinity in the Divinity School. The old Calvinism was preached with such fervor in the new Park-Street that local wits early christened the angle it faces “Brimstone Corner”, by which name it has been affectionately called ever since. Yet it is the coldest of Boston corners, and around it the harsh wintry winds swirl and snap and sting, and the proposal of Thomas Gold Appleton, rare coiner of Boston mots in his day, that the city fathers tether a shorn lamb here, is counted with the happier of Boston sayings.

The architect of the church was Peter Banner, an Englishman then ranking locally with Bulfinch, while the capitals of the beautiful steeple were designed by Solomon Willard, a native American architect, the designer of Bunker Hill Monument, next in prominence after Bulfinch. Only six years before the church was erected Park Street had been laid out and built, from plans by Bulfinch. This street had been from Colony times a lane called “Centry”, or “Sentry”, because it led to Beacon Hill (the highest peak of which early had that name) and it had been lined with grim old public buildings — the Granary at the lower end; the Workhouse and Bridewell; and the Almshouse at the upper end at Beacon Street (which, by the way, started humbly as “the lane leading to the almshouse”). Among these the Granary was unique. It was a paternal institution established by the town authorities in or about 1662 to supply grain to the poor or to those who desired to buy in small quantities, at an advance on the wholesale price of not more than ten per cent. A committee for the purchase of the grain, and a keeper of the Granary, were appointed annually by the selectmen. The building, a long, unlovely, wooden thing, had a capacity of some twelve thousand bushels. It was first set up on the then upper side of the Common within the plot occupied by the Granary Burying-ground, but in 1737 was removed to this corner. Then the burying-ground, which before had been called the South, took on its name. The Granary went out of service with the Revolution, and became a place of minor town offices and small shops. These buildings were done away with, and Park Street was begun in 1803 as a dignified approach to the new Bulfinch State House which had been erected in 1795. Where the Workhouse and Bridewell had been, appeared in 1804—1805 a row of fine Bulfinch houses. In 1804 in place of the old gambrel-roofed Almshouse rose an expansive mansion-house of the favored provincial type, built for Thomas Amory, merchant. Then the church replaced the Granary, handsomely finishing the entrance corner. Of the Bulfinch houses we see two or three yet remaining, transformed for business purposes. They were the homes at one time and another of Bostonians of leading. The attention of the Englishman was pointed to that numbered 4 as interesting from its association with the Quincy family. It became the home of the first Mayor Quincy after his retirement from the presidency of Harvard in 1854, and was occupied by him through the rest of his long and useful life, which closed in June, 1864, in his ninety-third year. His next door neighbor, at Number 3, was Josiah Quincy, Jr., the second Mayor Quincy, whose term covered the years 1846—1848.

Number 2, now rebuilt, was the last Boston house of John Lothrop Motley, in 1868— 1869, prior to his appointment as United States minister to England. Number 8, now the spacious home of the Union Club, was originally the town house of Abbott Lawrence of the distinguished Boston brother merchants, “A. & A. Lawrence”, and minister to the Court of St. James, appointed in 1849. Of the Amory house that replaced the Almshouse we also see a remnant reconstructed for business, and so happily as to retain something of its old-time air. It was the house which Lafayette occupied as the guest of the city during his stay in Boston on his visit of 1824. The part on Park Street (it was made with extensions into two and then four dwellings after Amory’s time) has an added interest as the home of the scholarly George Ticknor from 1830 till his death in 1871, where in his handsome library overlooking the Common he leisurely wrote his “History of Spanish Literature”, the work upon which he was engaged for twenty years.

It was going down this famous Park Street, we rather slyly told the Englishman, that Charles Sumner relieved Thackeray of a bundle that, true to his insular tradition, he was loath to carry. “The story itself may be only a tradition”, answered the Englishman.

On Tremont Street alongside the Mall — or Common Street as this part of the way continued to be called till the Town had become the City — houses were scant when Bennett wrote in 1740. Even when Park Street Church was built, there were only two houses on the street of more than one story, it is said. The first estate of note here appears to have been of the middle province period. It comprised a mansion-house on the Winter Street corner with a spacious garden extending down Winter Street and back of the present Hamilton Place. This seat certainly had notable associations. It was occupied by the troublesome royal governor, Sir Francis Bernard, during a part at least of his term from 1760 to his recall in 1769. During the Siege, it was one of the several headquarters of Earl Percy. After the Revolution, in 1780, it came into the possession of Samuel Breck, a Boston merchant of wealth and some distinction, who largely improved it. Then, as described in the “Recollections” of his son Samuel, it was, “for a city residence”, “remarkably fine”, with an acre of ground around the house divided into kitchen and flower gardens. While the Brecks had the place, the flower gardens were kept in neat order and, open to public view through a “palisade of great beauty”, were the admiration of all. The “Recollections” tell of a fête in these gardens given by the elder Breck on the news of the birth of the dauphin. “Drink”, they, relate, was distributed from hogsheads, while “the whole town was made welcome to the plentiful tables within doors.” Mr. Breck, removing to Philadelphia, in 1792 sold the estate to his brother-in-law, John Andrews, — the same of whom we spoke as the principal saver of the trees on this Mall at the time of the Siege, — also a Boston merchant of standing; and thereafter Mr. Andrews was its hospitable occupant till his death some years later. This Andrews was an unconscious contributor to local history, through a bundle of letters, racy and vivid, that he wrote from Boston during the Siege, which in after years came into the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society. They give the most intimate details of affairs and life in the beleaguered Town that we have in the chronicles of that time. He was then occupying a house on School Street just below the foot-passage to Court Square: and the day after the Evacuation he entertained Washington at a dinner there.

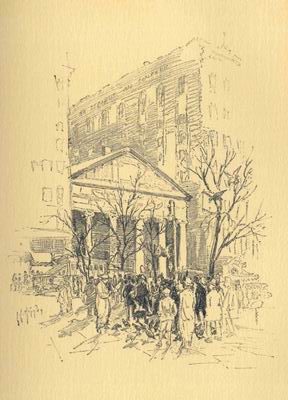

On Boston Common Mall in front of old Saint Paul's

On Winter Street, midway down, the site now marked by a tablet attached to the Winter Place side of the great store of Shepard, Norwell Company that covers it, was the house which Samuel Adams occupied during the last twenty years of his life, and where he died. This had been a royalist house and so confiscated. The house in which the patriot leader lived in the pre-Revolutionary period, and where he was born, was toward the water front, near Church Green. During the Siege it was practically ruined.

Where St. Paul’s stands and the towering shops which frame and dwarf it, was another late provincial estate that rivaled the Breck-Andrews place in extent, spreading between Winter and West streets. After the Revolution this was for a while known as the Swan place, from Colonel James Swan, its owner at that time, a remarkable man. He had been a merchant, a member of the “Boston Tea Party”, soldier of the Revolution, friend of Lafayette, speculator. Going to Paris, he had made a fortune there and lost it. After a brief season at home he returned to Paris, and engaging in large ventures during and after the French Revolution, acquired another fortune. Then he spent the last twenty-two years of his life in a French prison for a debt “not of his contracting”, and one which he deemed unjust. With constant litigation, judgment was finally in his favor, but he died a day or two after his release. Subsequent to the Swans’ day, mansion-house and estate were transformed into the “Washington Gardens”, a Boston Vauxhall, with its little amphitheater, or circus, its games, and other mildly alluring attractions. The Gardens were first opened for performances in July, 1815, and flourished for a considerable time.

St. Paul’s Church, now the Episcopal Cathedral, dates from 1819—1820, and, counting King’s Chapel, was the fourth Episcopal church to be built in Boston. Its founders were a group of men of wealth and prominence in the community, mostly parishioners of Trinity, the third Episcopal organization, founded in 1728, only five years after Christ Church; the edifice was then on Summer Street, north side, near Washington Street. Their purpose was to erect a costly and architecturally impressive church building; and when their Grecian-like temple of stone was finished, it seemed to them, as Phillips Brooks has said, “a triumph of architectural beauty and of fitness for the Church’s service.” It was the first monument in the Town of the Greek revival in architecture. The architects were Alexander Parris, an American engineer-architect, who afterward built the Quincy Market House; and Solomon Willard. Willard carved the Ionic capitals. It was planned to fill the pediment with a bas-relief representing Paul preaching at Athens, but the fund was insufficient to meet the expense of the work. Therefore, the rough stone we see was put in temporarily, to become a permanent fixture. In one of the tombs beneath the church Warren, who fell at Bunker Hill, was first buried, the remains afterward being removed to Forest Hills Cemetery in Roxbury, his birthplace. In another was interred the historian Prescott.

In 1810—1811 appeared “Colonnade Row”, the most notable embellishment of the way before the erection of St. Paul’s — a range of twenty-four handsome brick houses, designed by Bulfinch, extending from the south corner of West Street to the opening of Mason Street upon the thoroughfare. The name of Colonnade was given the row from the columns supporting a second-story balcony along the front, which constituted a striking feature of most of the houses The elegance of their design and their superb situation, overlooking the Mall and the Common’s expansive green to the open bay and the hills beyond, made them inviting to families of means; and Colonnade Row was at once admitted to the best society. After Lafayette’s visit, the name was changed, in the Frenchman’s honor, to “Fayette Place”; but this was retained only about a dozen years, when the old one was restored. The range held their ground as stately dwellings into the eighteen sixties. Then slowly one by one they were made over for business uses. Parts of façades of a few of them we yet discern in the present line of varied architecture. At the end of the Mall and looking across to the Hotel Touraine, we have the site of the modest mansion-house in which President John Quincy Adams sometime lived, and where was born his son, Charles Francis Adams, minister to England during the Civil War.

In the old days the train bands at muster spread all over the preserve with this Mall as the coign of vantage, we observed, as we three now turned into a side path to cross malls and paths trending westward. On the annual muster day in October, the Mall was lined with booths and tents for the sale of enticing edibles and drinkables — egg-nog, rum punch, spruce beer. Jollity and fun reigned throughout that holiday, albeit in Colony times the trainings opened and closed with prayer. All the train bands of the town and county were assembled. The line was formed alongside of the inner fence of the Mall and extended from Park Street to the Burying-ground here on the south side. There being no trees to interfere, the military evolutions occupied the whole field. Grand reviews filled up the morning hours, and the afternoon was devoted to sham fights. The fights were performed on the present parade ground on the west side. The training field remained the whole preserve till the nineteenth century. It was reduced to the limits of the parade ground in the eighteen fifties. The pasturage continued open till 1830; then the cows were finally banished.

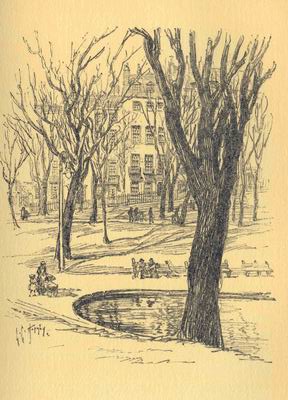

Across the Frog Pond to the old houses of Beacon Hill

Of the colonial tragedies of the Common we could point to no definite landmarks. Just where the “witches” were hanged, and the Quakers, cannot to-day be told. Even that the Quakers were hanged anywhere on the Common is now a question. Mr. M. J. Canavan, one of the most thorough of latter-day delvers into the truths of Boston’s history, and whose dictum on any nice point is accepted as authoritative, has thrown the Dry-as-dusts into dismay with the assertion that the four Quakers were hanged on Boston Neck, and seemingly proving it. Till Canavan spoke, the Dry-as-dusts were as sure that the Common was the place of their hanging as that they were hanged. Nor can we fix exactly the spot where the Indian, son of Matoonas, was hanged for murder in 1671, and where “a part of his body was to be seen upon a gibbet for five years after.” Nor precisely the place of the execution by shooting, in 1676, of brave old Matoonas himself, for his participation in King Philip’s War, betrayed into the authorities’ hands by tribal enemies, who were permitted to be his executioners. It can only be said that these, and the many other spectacular executions of men and women in the grim old days on this fair Green, were performed generally, if not invariably, on its western side. At first, it appears, the gallows was at or about the solitary “Great Elm,” and afterward was placed nearer the bottom of the Common, where the victims were hastily buried in the loose gravel of the beach there. We may imagine the scene of the hanging of the “witches” in 1648 and 1656, from gallows on the knoll neighboring the “Old Elm”, the site of which we find occupied by a descendant, and marked by a tablet. There were only two sacrifices to the witchcraft delusion here in Boston, and eight years apart; but the victims, as at Salem thirty-six and forty-four years later, were both women of talents above the common, and the delusion was deep-seated. After the first victim, Margaret Jones, had breathed her last, it was gravely recorded that “the same day and hour she was executed there was a very great tempest at Connecticut which blew down many trees, &c.” Perhaps it was at the solitary “Great Elm” that Matoonas was shot, for we read that he was “tied to a tree.” Maybe the holiday Ancient and Honorable warriors perform their evolutions on the parade ground on Artillery Election day, the first Monday of June, over the graves of the executed band of Indian prisoners, some thirty of them, of King Philip’s War. Or again, maybe they march and countermarch over the place where fell the British grenadier shot for desertion in 1768, the two British regiments then quartered in Boston “being present under arms.” On the parade ground, too, may have been the spectacle, after the Province had become the Commonwealth, of the hanging of Rachel Whall for highway robbery, which consisted in the snatching of a bonnet from the hand of another woman and running off with it.

Of the romances of the Common that daintiest love scene — the proposal of the Autocrat to the schoolmistress on the long mall running from Beacon Street Mall at the Joy Street entrance, across the Common’s whole length to the Boylston Tremont Streets corner — is recalled by the recently placed sign we observe at the head of this mall: “Oliver Wendell Holmes Path.” “We called it the long path and were fond of it. I felt very weak indeed (though of a tolerably robust habit) as we came opposite the head of this path on that morning. I think I tried to speak twice without making myself distinctly audible. At last I got out the question, — Will you take the long path with me? — Certainly, said the schoolmistress, — with much pleasure. —Think, — I said, — before you answer; if you take the long path with me now, I shall interpret it that we are to part no more! — The schoolmistress stepped back with a sudden movement, as if an arrow had struck her. One of the long granite blocks used as seats was hard by, — the one you may still see close by the Gingko tree. — Pray, sit down, — I said. — No, no, she answered softly, —I will walk the long path with you!” From the Autocrat’s day the mall has held Holmes’ happy title. The hard old granite seat has long since gone, but the Gingko tree remains.

At the Spruce Street entrance from Beacon Street we pass to Beacon Hill.