|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

III

COPP’S HILL AND OLD NORTH (CHRIST) CHURCH REGION

The North End earliest became the most populous part of the Town as well as the seat of Boston gentility, and about it longest clung the distinctive Old Boston flavor. This remained, indeed, well into the nineteenth century, long after its transformation into the foreign quarter it now essentially is, a little Italy in a good-sized Ghetto, with splashes of Greece, Poland, and Russia. Mellow old Bostonians of to-day remember it as the fascinating quarter of the City down to the eighteen sixties, still retaining, intermixed with alien innovations, a faded, shabby-genteel aspect and delightsome Old Boston characteristics in its native residents and in its architecture. And there are a few venerable folk remaining who can recall its appearance in the thirties as Colonel Henry Lee, that rare Boston personage of yesterday, has so charmingly pictured for us, — a “region of old shops, old taverns, old dwellings, old meeting-houses, old shipyards, old traditions, quaint, historical, romantic”; its narrow streets and narrower alleys “lined with old shops and old houses some of colonial date, with their many gables, their overhanging upper stories, their huge paneled chimneys, interspersed with aristocratic mansions of greater height and pretensions, flanked with outbuildings and surrounded by gardens”; clustered around the base of Copp’s Hill, “the old shipyards associated with the invincible ‘Old Iron-sides’ and a series of argosies of earlier or later dates, that had plied every sea on peaceful or warlike errands for two hundred years. The sound of the mallets and the hand axes were still to be heard; the smell of tar regaled the senses; you could chat with caulkers, riggers, and spar makers, and other web-footed brethren who had worked upon these ‘pageants of the sea’, and you could upon occasion witness the launch of these graceful wonderful masterpieces of their skill.”

The old-time charm the foreign occupation has not altogether effaced. There still remain the narrow streets and narrower alleys, and most of them have been permitted to retain their colonial or provincial names, as Salutation, Sun, Moon, Chair, Snowhill. Under the foreign veneer we may find a remnant of a colonial or provincial landmark; or, plastered with foreign signs, the battered front of some provincial worthy’s dwelling.

Copp’s Hill, reduced in height and circumference and shorn of its spurs, is reserved by the protected burying-ground that crowns it. This ancient burying-ground, Christ Church at its foot, and the “Paul Revere house” in neighboring North Square, constitute the three and only lures of the conventional “Seeing Boston” tourist to this dingy part of the modern city. The lads of Little Italy who swarm about the stranger as he mounts the gentle incline of Hull Street and offer themselves “for a nickel” as guides, can tell you more, or much with more accuracy, of the show points of the locality, than the native born, for they have been well tutored by the school mistresses of the neighborhood schools, and are marvelously quick in absorbing things American.

Though less “dollied up” than the other two historic graveyards — the King’s Chapel and the Granary, in the heart of the city—this enclosure is quainter. It is made up of three or four burying-grounds of different periods, intermingled and appearing as one. The oldest, which most interests us, is the northeasterly part bounded by Charter and Snowhill streets, back from the Hull-street entrance. It dates from 1660, which makes it in point of age next to the King’s Chapel ground, the oldest of the three, with the Granary ground a close third, that dating also from 1660 but a few months later than this. The part near Snowhill Street was reserved for the burial of slaves. In other parts are found numerous graves and tombs having monumental stones or slabs with armorial devices handsomely cut upon them; and some with quaint epitaphs. But in this, as in the other historic grounds, the stones in many instances do not mark the graves, for here and there in the laying out of paths stones were shuffled about remorselessly. And many graves are hopelessly lost, for in the dark days of the neglect of the place, stones were filched from their rightful places and utilized in the construction of chimneys on near-by houses, in building drains, and even for doorsteps. Others were pulled up and employed in closing old tombs in place of rotted coverings of plank. There are also cases of changed dates, as 1690 to 1620, and 1695-6 to 1625-6, more than five years before Boston was begun. These ingenious tricks were attributed to bad North End boys. A latter-day honest superintendent succeeded, through painstaking research, in recovering quite a number of the filched stones, and reset them in the ground, but with no relation to the graves they originally marked, for that was impossible.

Popular historic features of the hill other than the burying-ground concern the Revolution. Young America loves to point to the site of the redoubt which the Britishers threw up at the Siege, whence Burgoyne directed the fire of the battery during the Battle of Bunker Hill, and whence were shot the shells that set Charlestown ablaze. This work was in the southwest corner of the burying-ground. Then the summit was considerably higher than now, and the side of the hill fronting Charlestown was abrupt. The American schoolboy will tell you, too, how the British soldiers, during the Siege, amused themselves by making targets of the gravestones in the old burying-ground; and how the tablet on the tomb of Captain Daniel Malcom, merchant, boldly inscribed “A true Son of Liberty, a Friend of the Publick, an enemy to Oppression, and one of the foremost in Opposing the Revenue Acts in America”, was the most peppered with their bullets, and bears the marks of them to this day. In provincial times the hill was a favorite resort of the North Enders for celebrating holidays or momentous events. Tradition tells of monstrous bonfires on the summit on occasions of the receipt of great news. That in celebration of the surrender of Quebec, when “forty-five tar barrels, two cords of wood, a mast, spar, and boards, with fifty pounds of powder” were set off, must have been the grandest of its kind in Boston’s history. At the same time a bonfire of smaller proportions, yet big, was made on Fort Hill. It is related that on this gloriously festive occasion there were provided, at the cost of the Province, as were the bonfires, “thirty-two gallons of rum and much beer.” After the Revolution, on the seventeenth of June, 1786, when the Charles River bridge, the first bridge to be built from the Town to the mainland, was opened, guns were fired from where the British redoubt had been, simultaneously with the guns from Bunker Hill, while the chimes of Christ Church joined in a merry peal.

Christ Church, dating from 1723, the second Church of England establishment in Boston, and the oldest church now standing in the city, we see newly and faithfully restored to its original appearance, its parish house refurbished, the churchyard brushed up and lined with fresh young poplars, and the whole under the protecting wing of the Protestant Episcopal Bishop of Massachusetts. As a landmark of the Church of England in Puritan Boston, it is interesting to the churchman. But as a rare example of the so-called New England classic in architecture, it has a wider interest. In general outlines it follows Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Anne’s, Blackfriars. A substantial body of brick, with side walls of stone two and a half feet thick, and the belfry-tower with walls a foot thicker, the structure surely gave warrant for the hope expressed in the prayer of the Reverend Samuel Myles, the devout rector of King’s Chapel, at the laying of the corner-stone: “May the gates of Hell never prevail against it.” The original spire surmounting the tower, attributed to William Price, was blown down in an October gale in 1802, but the present one, built in 1807, from a model by Bulfinch, is said to be a faithful reproduction of it in proportions and symmetry. The tower chimes, comprising eight sweet-toned bells, still the most melodious in the city, were hung in 1744, and were the first peal brought to the country, from England, as the inscription on one of them states —“we are the first ring of Bells cast for the British Empire in North America, A. R., 1744.” Each bell tells its own story, or records a date of the church, or a sentiment, inscribed around its crown. They were bought by subscription of the wealthy parishioners. A few years after their installation, a guild of eight bell-ringers, all young men, was formed, one of whom is said to have been Paul Revere. The tablet on the tower front relates the story that Revere’s signal lanterns that “warned the country of the march of the British troops to Lexington and Concord”, were “displayed in the steeple of this church April 18, 1775”; and the story is firmly fixed in the official guide to the church; yet there are those who question the statement, and as firmly fix in history the place of the lights to be the belfry or steeple of the genuine “Old North” Church —the meeting-house that stood in North Square till the Siege, when it was pulled down by the British soldiers and used for firewood.

In the restored interior we find in place all the choice relics that embellished the provincial church, and of which the guide-books tell: the brass chandeliers, spoil of a privateersman; the statuettes in front of the organ, intended for a Canadian convent and captured by a Boston-owned privateer from a French ship during the French and Indian War of 1746, and presented by the privateer’s commander, a parishioner; the “Vinegar” Bible, and the prayer-books bearing the royal arms, given by George II in 1733. And among the mural ornaments, — the bust of Washington said to have been modeled from a plaster bust made in Boston in 1790, and the first memorial of Washington set up in a public place. Beneath the church and the tower are many tombs. In one of these was temporarily buried Major Pitcairn of the British Marines, he who led the advance guard at Lexington and Concord with that cry, “Disperse, ye Rebels!” which brought upon that amiable gentleman-soldier, beloved of his men, the odium of the Americans, and who fell mortally wounded at Bunker Hill. The gruesome tale is told that when his relatives in England sent for his remains, and his monument was placed in Westminster Abbey, the perplexed sexton, unable to identify them, substituted another body, that of a British lieutenant who had resembled him in figure and height, which was duly forwarded as Major Pitcairn’s.

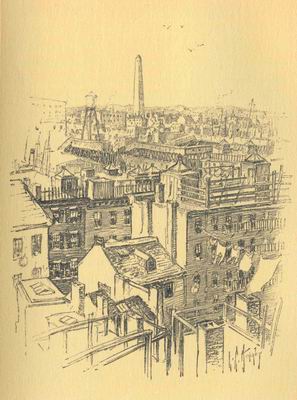

From the belfry of Christ Church, Gage witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill. From the same point of view the Artist makes a picture of Bunker Hill Monument of to-day for our English guest.

In North Square we are in the once fair center of provincial elegance completely metamorphosed. Save the colonial touch in the little old Paul Revere house, with projecting second story, and the colonial names of the diverging ways — Moon, Sun Court and Garden Court streets—all semblance of Oldest Boston is stamped out. Antiquary can only indicate the spots where “here stood”; imagination must do the rest.

We remarked the Revere house as worth more than a passing glance merely as the dwelling-place of Longfellow’s hero of the Revolution. It was old when Revere bought it in 1770, for it was built after the “great fire” of November, 1676, —the sixth “great fire” in the Puritan Town, — and, moreover, it replaces the house of Increase Mather, the parsonage of the First North Church, which went down with the meeting-house and nearly fifty other dwelling-houses, in that disaster. Revere moved here from Fish Street (Ann, now North) perhaps before 1770, and it was his home from that time till 1800, when, having prospered in his cannon and bell foundry, he bought a grander house on neighboring Charter Street, by Revere Place, where he spent the remainder of his days, and died in 1818. His foundry, which he established after the peace, was near the foot of Foster Street, not far from his Charter Street house.

It was in the upper windows of this little, low-browed, North Square house that Revere displayed those awful illuminated pictures upon the evening of the first anniversary of the “Boston Massacre”, which as we read in the Gazette of that week, struck the assemblage drawn hither with “solemn silence” while “their countenances were covered with a melancholy gloom.” And well might they have shuddered. In the middle window appeared a realistic view of the “Massacre.” The north window held the “Genius of Liberty,” a sitting figure, holding aloft a liberty cap, and trampling under foot a soldier hugging a serpent, the emblem of military tyranny. In the south window an obelisk displaying the names of the five victims stood behind a bust of the boy, Snyder, who was killed a few days before the affair by a Tory “informer” in the struggle with a crowd before a shop, “marked” secretly as a Tory shop to be boycotted; and in the background, a shadowy, gory figure, beneath which was this couplet: “Snider’s pale ghost fresh bleeding stands, And Vengeance for his death demands!” Revere was indeed a stalwart patriot, but he was no artist, and the execution of these presentations may have contributed no small part to the gloom of the populace contemplating them.

We pointed out the site of the first North Church and its successor, built upon its ruins the year after the fire, which became the Old North — at the head of the square between Garden Court and Moon Streets. Nothing is preserved to us in picture or adequate description of either of these meeting-houses of the Second Church of Boston, which was formed in 1649, and for more than three-quarters of a century, from 1664, the pulpit of the famous Mathers —Increase; Cotton, son of Increase; and Samuel, son of Cotton. Although the house of 1677 was close upon a century old at the Revolution, it is said to have been still a fairly rugged building, and its destruction by the British soldiers for fuel during that cold winter of the Siege is called wanton by the historians. The Church remained homeless, though not dispersed, from the beginning of the Siege to 1779, when it acquired a meeting-house on Hanover Street near by.

Increase Mather, after the burning of his house in the fire of 1676, built on Hanover Street, just below Bennett Street, and a remnant of this house, number 350, we may yet see, covered with foreign signs. Cotton Mather passed a part of his boyhood in the Hanover Street house. After he became the minister of the North Church, he bought a brick mansion-house hard by, also on Hanover Street, which the first minister of the North Church, John Mayo, had occupied. Samuel Mather’s house was on Moon Street. The tomb of the Mathers we saw in Copp’s Hill Burying-ground. North Square was a military rendezvous during the Siege. Barracks were here, and the fine houses in the neighborhood were used as quarters for the officers. Major Pitcairn was occupying the Robert Shaw mansion, which stood opposite Revere’s little house, when he went to his fate at Breed’s Hill.

In Garden Court Street we pointed to the sites of two of those aristocratic mansions of which Colonel Lee spoke, in height and pretension overtopping their neighbors. These were the Hutchinson and the Clark-Frankland mansions, stateliest of their day, which have figured in romance and story. They formed, with their courtyards and gardens, the west side of the court. The Hutchinson’s garden back of the house extended to Hanover and Fleet Streets.

The Hutchinson mansion was built in 1710 for the opulent merchant, Thomas Hutchinson, father of the more eminent Thomas Hutchinson, historian, chief justice, royal governor; the Clark-Frankland followed two or three years after, built for William Clark, as rich a merchant as Hutchinson, and somewhat grander to outvie his neighbor. Clark died in 1742 and was buried in a grand sculptured vault in Copp’s Hill Burying-ground, which some years after was taken possession of by a lawless sexton who caused his own name to be inscribed above the merchant’s; and when he came to die his humbler remains were deposited in the merchant’s place.

The Clark-Frankland mansion acquired its hyphenated title after Clark’s day, with its purchase in 1756 by Sir Harry Frankland, gallant and favored, great-grandson of Frances Cromwell, daughter of the Protector, who chose to be collector of Boston rather than governor of the Province when George II offered him his choice, and who became the lover of lovely Agnes Surriage, maid of the Fountain Inn in old Marblehead, the heroine of Holmes’ ballad and Bynner’s novel. Here Sir Harry brought the beautiful girl, now his wife, and the handsome pair richly entertained the gentry of the Town, with the assistance of Thomas, the French cook, mention of whose hiring at fifteen dollars a month Sir Harry makes in his diary. They lived here but one short year, when Sir Harry was transferred to Lisbon, this time as consul. After his death, in England, in 1768, the Lady Agnes returned to Boston and to this mansion, and remained till the outbreak of the Revolution. The story of the gallant courtesies that attended her leaving the Town at the Siege is one of the prettiest of the incidents of that troublous time. After the Siege, she went back to England, and presently married a country banker and lived serenely ever after, till her death in 1783.

Bunker Hill Monument from the Belfry of Christ Church

The Hutchinson mansion was the birthplace of Thomas Hutchinson, 2d, and here, and at his country-seat in the beautiful suburb of Milton, he lived through his whole career, till his departure to England in June, 1775, before the Battle of Bunker Hill, to report to the king the state of affairs in Boston, never to return, but to die there in exile yearning for his old home. That he meant to be true to Boston, to which he was devotedly attached, is now beyond question. In this Garden Court house, Hutchinson wrote his “History of Massachusetts,” and when the mansion was wickedly sacked by the anti-Stamp Act mob, on an August night of 1765, his priceless manuscripts were scattered about the court with his fine books and other treasures, but, happily, a neighbor gathered them up, and so they were saved. The two mansions lingered till 1833, when the widening of Bell Alley as an extension of Prince Street swept them away. Colonel Lee remembered them in their picturesque decadence festooned with Virginia creeper.

Returning from the North End by way of Hanover Street, we make a detour through short, winding Marshall Lane — the sign foolishly says Street — which issues on Union Street, and was originally a short cut from Union Street to the Mill Creek which connected the North, or Mill, Cove, with the Great Cove. Here, set into the corner building above the sidewalk, we come upon the “Boston Stone, 1737”, a familiar provincial landmark. It is the remnant, we explain, of a paint mill brought out from England about the year 1700 and used by a painter who had his shop here. The round stone was the grinder. The monument was placed after the painter’s day, in imitation of the London Stone, to serve as a direction for shops in the neighborhood. The painter’s shop was known as the “Painter’s Arms” from his carved sign fashioned after the arms of the Painter’s Guild in London, and still preserved as an ornament, set in the Hanover Street face of the corner building, on the site of the shop. A similar guide post, called the “Union Stone”, was at a later day placed at the Union-street entrance of the lane, before the low, brick, pitch-roofed, little eighteenth-century building we see yet lingering on the upper corner here. This house was in latter provincial times Hopestill Capen’s fashionable dry goods shop, in which, in his handsome youth, Benjamin Thompson of Woburn, later to become the famous Count Rumford, and named with Benjamin Franklin as “the most distinguished for philosophical genius that this country had produced”, was an apprenticed clerk quite popular with the lady customers.

The Paul Revere House, North Square

Turning into Union Street, and so to Hanover Street again, we pass the site, somewhere in the street-way at this junction, of the dwelling and chandlery shop of Josiah Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s father, at the sign of the Blue Ball, where Benjamin spent his boyhood. The landmark remained till the late eighteen fifties, when it disappeared with a widening of Hanover Street. But the Blue Ball still remains, an honored relic in the Bostonian Society’s collection in the Old State House. On Union Street, across Hanover, where is a tunnel station, we have the site of a famous Revolutionary landmark — the Green Dragon Tavern, headquarters of the patriot leaders; where the “Tea Party” was organized; where later met the North End Caucus, chief of the political clubs that gave the name caucus to our American political nomenclature; the rendezvous of the night patrol of Boston mechanics instituted to watch upon British and Tory movements before Lexington and Concord. The Green Dragon was also the first home of the Freemasons, when, in 1752, the pioneer St. Andrew Lodge was organized, and, in 1769, the first Grand Lodge of the Province, with Joseph Warren — the Warren who fell at Bunker Hill —as master.