| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER III

MYTHS AND MONUMENTS I THE Indian worshipped the Inca, his sovereign, because of his divine origin, being the descendant of Manco Ccapac, founder of his race, who was the son of the Sun. Thus, religion was the substance of the empire. But as the Temple of the Sun at Cuzco was a pantheon of idols, sacred each one in the mind of some visiting chieftain, though always remaining the Sun Temple, so the religion itself was a synthesis of all the beliefs which those idols represented; blended yet dominated by the all-searching light of the Sun. This may explain, for instance, the confusion of Pachacamac, the supreme deity of the ancient coast tribes, with Uiracocha of the mountains, whom Acosta, among others, declares to be one and the same. Clear-cut distinctions are impossible. The stories are all vague, even among confident writers of legends.  A Swinging Bridge near Jauja As to the Sun's descent, the wise men of the Incas learned from their predecessors that he was made by The Ancient Cause, The First Beginning, The Maker of All Created Things, The Supreme Deity, Ilia Tici Uira Cocha — the four ultimate, visible forms of the Infinite, to quote the Peruvian Star-chart of Salcamayhua. There is in Quichua a word to express "the-essence-of-being-in-general-as-existent-in-humanity." Sometimes the name is given as Con Tici Uiracocha, an identification with the supreme god, Con, the center of another group of legends of belief. The mystery surrounding this great, invisible god, generally called Uiracocha, is as complete now as it was to the Sun-worshipping Incas, a sort of dim background for the glittering splendor of Sun-ritual. Uiracocha has many identities: Uiracocha, the Supreme God; Uiracocha, the hero-god, the white and bearded man in long robes, who with a strange animal in his hand, appeared to that Inca afterwards called by his name, tending the flocks of the Sun among the tops of the Andes; Uiracocha, who raised up an army for the Inca on the Field of Blood out of stones that he set on fire from a sling of gold; he who changed the revelers of Tiahuanacu to stone in wrath. (However misty the connection between Uiracocha, stones, and human beings, it is certain that Peruvians held stones in great awe. The temple to Uiracocha, the war-god, is at the foot of an extinct volcano whence a lava stream had issued. It is paved with black and made of carved and polished stone. The interior was obscure, with an altar for human sacrifices.) Uiracocha who, as Betanzos relates, came out of a lake when all was dark, lord of light and lord of wind, who, as dawn appeared, spread his mantle over the waves of the lake and was wafted away into the rays of morning light. The curling waves followed his evanescent passage, and so he was called Uiracocha, the Foam of the Sea. He gave his wand to the chief in the House of the Dawn. It afterwards became the golden staff of Manco Ccapac, his son. Uiracocha was the universal god of the Quichua-speaking people. The Sun was peculiar to the Incas. The hazy red deity Con was the personification of subterranean fire. "He is light as air, has neither arms nor legs, nor muscles nor bones, nor joints nor nerves nor flesh, but runs very fast in all directions." He came from the sea and flattened the hills and filled up the valleys, and by his simple word gave life to man. Viciously he converted the race of men he had created into black cats and other horrible animals, devastated the earth, deprived it of rain, and — retreated into the sea. His first temple was a volcano. This left a free field for his equally omnipotent, equally hazy brother Pachacamac, who benignly created another race of men. Since Pachacamac was invisible and beyond their conception, the Incas built him no temples, but gave him secretly a superstitious worship, bowing their heads, lifting their eyes, and kissing the air as evidences of the reverence they felt at the mention of his name. Here is a prayer reported by Geronimo de Ore: "O Pachacamac, thou who hast existed from the beginning, and shalt exist unto the end, powerful and pitiful; who createdst man by saying, 'Let man be;' who defendest us from evil, and preservest our life and health; — art thou in the sky or in the earth, in the clouds or in the depths? Hear the voice of him who implores thee, and grant him his petitions. Give us life everlasting, preserve us, and accept this our sacrifice." The Inca mind could not reconcile the anterior existence of Uiracocha, Con, and Pachacamac with Sun-supremacy. We find them all called sons of the Sun, and so their importance could consistently fade away. The origin of the two first Incas was mystery-veiled. Men discussed whether they were saved from the primeval waters robed in garments of light, or whether they came from three shining eggs laid by the lightning in a mountain cave after the deluge. Did they escape from the lower world through a giant reed, or were they imprisoned in a cave, over which Uiracocha appeared with wings of brilliant feathers to give Manco Ccapac the insignia — the scarlet fillet and the round gold plates? Some thought they emerged from Paccari-tampu, the Lodgings of the Dawn, not far from Cuzco. They had been led thither through caverns of the earth. Sarmiento relates that the Incas came out of a rich window, by order of Uiracocha, without parentage. The first Inca had an enchanted bird and a staff of gold, and came conferring fairy-tale benefits to mankind. The legend most widely accepted taught that the Incas, who in the person of Manco Ccapac and his wife and sister Mama Ocllo came out of the cave of Paccari-tampu, were children of the Sun. He himself placed them on the Island of Titicaca and told them to wander until they should reach a place where their wedge of gold would be swallowed up by the ground at a touch. There they should build the capital of their empire. At the foot of the fortress of Sachsahuaman it disappeared, and so the city of Cuzco, the Navel of the World, was founded. The poetic fiction of all these legends conceals an historic background of curious details. But with Father Acosta we should consider that "it is not matter of any great importance to know what the Indians themselves report of their beginning, being more like unto dreams than to true histories." He continued: "They believe confidently they were created at their first beginning at this new world where they now dwell. But we have freed them of this error by our faith, which teacheth us that all men came from the first man." Besides all this maze of divinity and a symbolic astronomy, everything in nature had for them a soul that they might pray to for help. Not only the sun, moon, stars, thunder, and lightning, the rainbow, the elements, and rivers, but that deep sea from which they issued had a mysterious worship. They adored high mountains, homes of majestic gods whom they never saw, whence streams proceeded to water their terraces. They sacrificed to distant objects by blowing the ashes of burnt sacrifices into the air, offering them to the hills and to the wind. They adored all great stones, the mouths of rivers, all things in nature different from the rest, and offered to them small stones or a handful of earth or an eyelash. Moreover, there was an elaborate fetishism. They had idols with a personal interest; they carried talismans; they had miniature domestic altars, where they offered chicha or flowers. They tried to appease things that might injure them. They drank a handful of water from a dangerous river before crossing, and ate a bit of the stone which had harmed them, and offered in sacrifice a leaf of coca. The mysteries of coca epitomize the country where it grows. It not only fortifies the teeth, controlling mountain sickness, preventing fatigue, keeping off disease, strengthening broken bones; it cheers the spirit and invigorates the mind, and gives courage to perform impossible tasks. Its juice softens hard veins of metal. The odor of burning coca propitiates the deities-of-metals, who would render the mountains impenetrable without it. Coca-leaves in the mouths of the dead insure a welcome in lands beyond. No wonder it was the divine plant of the Incas. A sacrifice at festivals, its smoke an offering to the gods, whose priests chewed the solemn herb to gain their favor, it was a benediction for any enterprise. Mama-coca, its spirit, was worshipped. Coca, preferred to gold, silver, or precious stones, was dubbed by the Spaniards "una elusión del demonio." II

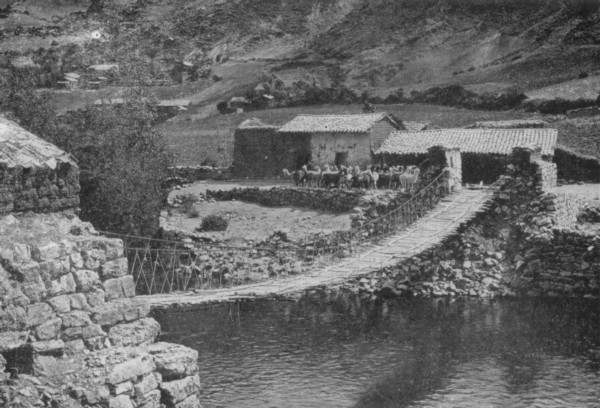

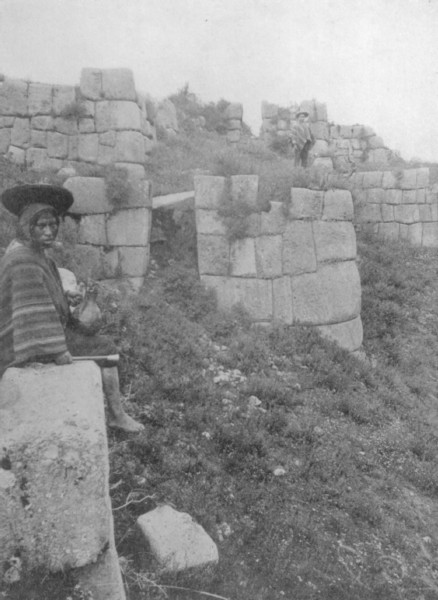

Almost as well known as the stories of silver and gold from Peru are those relating to its mammoth buildings made of mammoth stones. The ruins are a better witness to the greatness of the ancient Peruvians than the wealth looted from them. It is the first fact mentioned by a homecoming traveler that there is a twelve-cornered stone in the Street of Triumph in Cuzco, and into and around each corner other stones are so perfectly fitted that a knife-blade cannot be inserted between them. That fact is perfectly true. So also is the fact that ancient Peruvians transported stones weighing tons with llamas and human beings as their only beasts of burden. They lifted them to great heights without machinery, cut them without steel implements, blasted them without gunpowder, and polished by rubbing them with other stones and bundles of rough grass. They had no resources in building but their own energy. The vast "stones were raised by social institutions, supplying want of instruments by numbers of people." This world of ruins, comparable to Egypt, "is isolated in the region of the clouds." Stupendous scenes upon these elevated plains were object lessons — nearness of gigantic peaks, appalling depth of chasms. The Incas learned much from nature: from salt-strewn deserts to lay waste their criminals' property, sowing their fields with salt; from the sea, maker of terraces. They finished off the mountain-sides with small andenes, or hanging gardens, which received the flow of water bestowed by the Inca upon his subjects with every patch of ground. They brought loam from the jungle in baskets and created land upon bare rocks. Where opportunity offered, the terraces widened, following the natural excrescences of the mountain. And when nature failed to point lessons, models were provided by far-receding civilizations so remote that they almost seemed to have relapsed into the domain of nature. Each served as the foundation for the next, like the rhythmic life of the jungle. Ancient Peruvians hesitated at nothing. They built an artificial city on a high, cold, almost waterless, plain, with a palace for the Inca to visit in, a garrison for his protection, and magazines and granaries for his soldiers' food. Countless royal palaces, too, their niches covered with plates of gold, and convents like the House of the Virgins of the Sun in Cuzco, were duplicated all over the empire for other wives of the Inca as he chose among them, "storehouses sheltering his tribute in women." There were baths and fountains and places of pleasure and round stone chulpas, towers of the dead. Since no one traveled except by order of the Inca, the highways were reserved for himself, the armies, and the chasqui, or royal runners. From Zarate to Humboldt, they have been described as fit to rank with the seven wonders of the world. One highway pierced walls of solid rock, crossing profound chasms and the treacherous marshes of the puna on walls of solid masonry. Being a pedestrian road, it slipped in flights of stone steps over the brow of the mountains. It traversed the whole empire for two thousand miles among the mountain-tops. The other, flanked by mud walls, lay along the low deserts of the coast, "shaded by trees whose branches hung over the road loaded with fruit, and filled with parrots and other birds," to quote Cieza de Leon. Humboldt said that "part of the coast road was macadamized." At regular intervals, "every ten thousand paces," tambos were scattered along the roads, houses of pleasure for the Inca and waiting-houses for the relays of messengers of the Sun as they bore news of royal necessity, or brought fish from the sea or other delicacies from distant provinces to the Inca's table. Garcilasso describes the stone stairs up to these inns " where the chairmen who carried the sedans did usually rest, where the Incas did sit for some time taking the air, and surveying in a most pleasant prospect all the high and lower parts of the mountains, which wore their coverings of snow, or on which the snow was falling, for from the tops of some mountains one might see a hundred leagues round." The Incas threw a swinging osier-bridge of spider-web construction across a vicious torrent to lead their armies over. So-called historians tell of bridges of feathers used in Inca days, but, as Garcilasso adds, "omit to declare the manner and fashion of them!" The secrets of the Inca ruins are not yet told. For their industry moulded underground as well, connecting palaces and convents by hidden passageways, and chambers and depositories for army supplies like those made by the great Yupanqui in his campaign against the Chimus. The subterranean system of water-works was stupendous. Near Cajamarca is a channel several hundred miles long paved with flagstones throughout its entire length. It forms the outlet to a little lake. Another aqueduct traversed the whole province of Cuntisuyu, twelve feet deep and over one hundred and twenty leagues long, leading waters of the snows to barren plains. Water was stored in cisterns on the mountain-tops. " They conducted rivers in straightened channels through hills of solid rock," they brought water through pipes of gold from distant hot and cold springs, whose sources are now unknown. It trickled into the baths of the Inca through golden jaws of animals, birds, or snakes, and then welled over through properly regulated pathways to the terraces, where growing things were in want of irrigation.  An Heir of the "Makers of Ruins" This civilization had taken ages to evolve, as the development of certain plants and animals alone would show. It was reduced in a few years to an empire of ruin. One shivers at the " hideous energy of destruction evinced by man." But in spite of all that has been done to annihilate the achievements of the Incas, benefits accruing from them still remain. "Makers of ruins" indeed, yet by them the present flimsy civilization exists. Upon their terraces, climbing to the mountain-tops, Indians now live in mud huts, little towns clutching at a far-off slope, apparently deserted but for the cemetery. Irrigating prospectors stand aghast before their mighty systems. The railway builder may take lessons in road construction. There is practical value in ruins, if from them comes inspiration for modem industry. And there is poetry in ruins, because they speak of men and things which are gone, never to return, "the shrines of by-gone ideals, makable when they were made and then only." |