| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER II

A MEGALITHIC CITY AND A SACRED LAKE I THERE is something more mysterious than the sea, and that is the desert; something more mysterious than the desert, and that is the mountains; something more mysterious than the mountains, and that is the jungle. Yet there is something with a deeper mystery than all — the tradition of a great race that has struggled to a climax and subsided. Where is there a more unbridled ocean? Where a more pitiless desert? Where other Andes? Where so limitless a jungle? And where, in the history of the whole world, so picturesque a dynasty — whose god was the Sun, whose insignia the rainbow, who dwelt in houses lined with gold, who tamed the earth's resources so that their aqueducts in a rainless land are still ministering to the descendants of a people who destroyed them, and who left not one written word to testify that they had ever been created at all. What can be said of the Incas, the theme of romance ever since the greed of the Spaniard reduced them to a legend — romances pale indeed beside facts recorded by sober historians? A people who used copper for iron, quipus for writing, llamas for horses; who sacrificed condors and humming-birds to their gods on the frozen plains; whose accumulations of precious metals exceeded stories of Ophir's wealth; whose ears were enlarged that they might better hear the complaints of the oppressed, and who were brought to destruction by a handful of adventurers whom the whole training of the people had led them to worship as gods. Yet the Incas were only the final stage in a series of races that flourished on the heights of Peru back through the ages. They were but the last flicker of a guttering civilization without a name, which has left only a few silent ruins built by unknown peoples, of whom these "symptoms of architecture" reveal to us the forgotten existence. The mystery that fires our imagination in contemplating the Incas had shrouded their predecessors from them with an impenetrable veil. Humboldt once remarked that the problem of the first population of America is no more the province of history than questions on the origin of plants and animals are part of natural science. In considering this megalithic age, we have to do with pure speculation, not with any legitimate domain of knowledge. Learned treatises end only with a question. Dr. Bingham has recently discovered among these mountains glacial human bones, possibly twenty thousand to forty thousand years old. They may shed new light upon the identity of the makers of those mysterious terraces which appear coeval with the creation of the world. Vestiges of past civilizations are everywhere about, "monuments which themselves memorials need;" terraces hollowed out of the mountains to the very summits, bits of stone walls, roads, aqueducts, or an occasional stone idol with a shallow vessel for the blood of victims, perhaps a staring face on a pillar with projecting tusks and snakes intertwined on its cheeks. Tiahuanacu was made by a race which as far antedates the Incas as they the dominant race to come. Everything to do with it is remote and forgotten. Of necessity even its name is modem, having been given by the Inca Yupanqui to his "resting-place." The great pillars of the City of the Phoenix rise from the roof of the world, "as strong and as freshly new as the day when they were raised upon these frozen heights by means which are a mystery." Single stones measure thirty feet in length. Heads of huge statues lie about and hard black stones difficult to hew, the corners as sharp as when chiseled before the memory of man. Niches and doorways are cut from the middle of single blocks, whose corners are perfect right angles. Many finely sculptured stones are now used for grinding chocolate, some of the larger ones for making railroads. Prehistoric idols lean as doorkeepers against flimsy, modem walls in the almost deserted modem town, and one weird face has found its way as far as the Alameda in La Paz. Beyond the protecting opening of a still perfect monolith lies the burial-place for still-born Christian children. A monolithic doorway, beautifully sculptured, lies broken in two by lightning. A square-headed, legless, impenetrable god, speaking from right-angled lips, still stares from behind his square eyelids. Weeping three square tears from each eye, he surveys the waste and desolation about him, just as he looked unmoved upon the golden pageants of Inca days that did him honor as a superhuman deity who had sprung into being in one night with a whole city about him. His hands wield snaky-necked scepters, each the head of a condor, the lightning bird; and rows of square little worshippers in wings and condor-fringes kneel beneath crowns of rays fading off into the heads of birds with reversed combs. No one yet knows the meaning of the sculptured deity which confused Inca amautas (wise men) a thousand years ago. Though the Creator is supposed to have lived in Tiahuanacu, an eminent German, Rudolph Falb, says the weeping god is a hero of the flood, his tears the symbol of the deluge. A tradition of the sixteenth century ascribes these monuments to an age before the appearance of the sun in the heavens. Their builders were destroyed by a flood sent by the wrathful god, Con Tici Uiracocha, who came from the south, converting "heights into plains and plains into tall heights, causing springs to flow out of bare rocks." Half in regret that he had destroyed his race of men, he created sun and moon to render visible the waste he had made. This

information is as accurate and authentic as any which a long line of

distinguished explorers and archeologists have been able to

substitute for it. Men of sane judgment agree in admitting that there

is nothing to justify any conclusion. But they also agree that the

significance of Tiahuanacu exceeds everything hitherto discovered in

Peru. It recalls Carnac and Philae. It stands with the dolmens of

Brittany, Stonehenge, and the cyclopean terraces of the South Sea

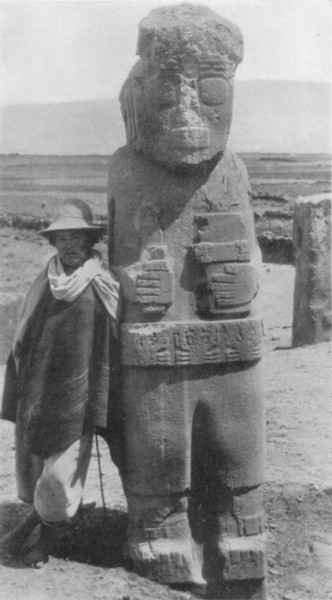

Islands, as a great riddle of human history.  A God of Tiahuanacu II

Dropped in the bottom of yawning red gulfs, with snow-peaks glistening overhead, are wild valleys of differing climates, the mighty quebradas of the Andes. These canyons, which the famous hanging bridges used to span, intersect the wilderness. They lie in dusk while the overarching cliffs are bathed in full sunlight, for sunrise and sunset are within a few hours of each other. The warm air, steaming upward, pushes the snow boundary far above. Strata of black sand on the valley's walls have been tunneled by cave-dwellers of ancient times. French sisters of charity move about in cloisters under eucalyptus trees. Such a surprise is Yucay, tucked in snugly between two mountains, wrapped in soft air and scents of unknown flowers, the loveliest spot in all the empire of the Incas. Streams of clear water descend to it from above and form the smooth, deep river of Yucay. The Incas sought it out for their gardens of pleasure and were lulled to rest by bells of gold tied to the hammocks in which they slept. Water has a very tranquillizing effect. It sweeps along a valley, and the jagged remnants of volcanic action are smoothed out into long undulating lines. Water collects in all crevices; lakes green as iron vitriol, fed by subterranean springs, lie in the surly country like jewels in their setting. When night shadows have settled in the valleys, the alpine glow is reflected in the quiet surface. There are no fish in the lake of Chinchaycocha, Laguna de Reyes. Though their element is water and they die in air, here they die in pure water for lack of air. The ingahuallpa sings a monotonous note from the bank at the close of every hour during the night. The outlet of the lake is narrow and deep, and its clear water flows smoothly and without noise. All the lakes have their secrets. The little lake of Orcos still holds the golden chain with links wrist-thick made by Huayna Ccapac at the birth of his eldest son. It encompassed the market-place of Cuzco. It was so weighty that "two hundred Indians having seized the links of it to the rings in their ears were scarce able to raise it from the ground." After the coming of the Spaniards, it was thrown for safe-keeping into this round, deep pool filled by unknown springs. Safe indeed it is. Orcos has not given up its charge, though repeated attempts have been made to reach the bottom. Trying to drain it by a sluice and trench, the Spaniards "unhappily crossed upon a vein of hard rock, at which, pecking a long time, they found that they struck more fire out of it than they drew water" — the opposite element from the one they expected. Up against the sky lies a sea where men sail in boats of grass — Lake Titicaca, where ships are silently struck by lightning without crash of thunder. On these high seas the navigator has to go by instinct, because of the loadstone round about — magnetic iron, it is now less picturesquely called. Saint Elmo's fire blazes from ships' masts on stormy nights. Sometimes a pointed tongue of black clouds swings from above, "like the trunk of some gigantic elephant searching the ground." A similar one raises itself from the surface of the water, slapping back and forth, seeking the point of the tongue above, and when they have found each other, they join in a mighty, black column, out of which burst thunder and lightning. It whirls off everything within reach and sucks down a passing balsa (boat of reeds) into a depth never sounded. The water of Lake Titicaca is ice-cold and brackish. Its strangely fashioned fishes never come to the surface. It is inhabited by great animals like sea-cows, occasionally seen resting on a beach of some remote inlet. The grottoes along the shore are guarded by gray and black night herons and inhabited by the sea-cow or other monsters! Queer birds haunt the wide stretches of totora growing along the shore, reeds whose stems are used for making boats, and whose tips are used as salad. Here live the stately puna geese, dazzling white, with green wings shading into violet; black water-hens, white quinlla, dark green yanahuico with long, thin, bent bills, finely etched ducks, ibises, licli, metallically bright, and sea-gulls from the Atlantic. Coal is found on the shores of Titicaca, which suggests a mystery. At what elevation could tropical coal plants grow? The bones of mastodons are also here. But rocks even higher up are smoothed as if by waves, and beaches are found like those of the actual sea. Both Humboldt and Darwin found shells, once crawling on the bottom of the sea, now embedded fourteen thousand feet above its level. Small lakes are sources of small rivers, by which they are emptied. But great Titicaca forms no stream at all. Its outlet has no outlet of its own. The rush of nauseous water is poured into a shallow lake-twin not far away — Poopo, through whose mysterious whirlpools the water drops back again in subterranean escapes. This tumultuous torrent, the Desaguadero, was spanned in former days by a bridge of reeds. Recent measurements show that the level of these two lakes is constantly lowering, and eventually they will disappear. They were once the source of the greatest river in the world, but some day there will be only a salty deposit in the hollows they now fill. Titi, the cat, kaka, the rock, Lake Titicaca was named for a little island within it, around which cluster legends of the origins of things. It was the most revered shrine in the empire of the Incas. Neither the wide fields of Chita, where the flocks of the Sun gamboled, nor the valley of Yucay could equal this enchanted isle of Titicaca. Before the arrival of man, the island was inhabited by a tiger, carrying on its head a magnificent ruby, whose light illuminated the whole lake as the afterglow the snow-covered peaks above. The Hawaiians have an expression for the shifting of colors in a rainbow. The Indians on Lake Titicaca have special words for the glow of fading sunlight on the mountain summits and the purple of the glaciers in their hollows. The Sun had preserved himself from the flood by hiding in the depths of Lake Titicaca. This was his island, out of whose sacred rock, after the deluge, he soared like a big flame into the sky. His footsteps are still to be seen perpetuated in iron ore. The original Incas were let down by the Sun, their father, on to the small island and commanded to go forth to teach the savage inhabitants. But the worship given this spot by the Incas was only absorbed in that of former times. This "Island of the Wild Cat" is a field of aboriginal myth and tradition. The sacred cliff where the Sun had risen was covered by the Incas with sheets of gold and silver, "so that, in rising, he might see the whole rock ablaze, a signal to worship." "Sixteen hundred attendants manufactured chicha to throw at it, and pilgrims from the entire empire brought offerings of silver and gold." Garcilasso says that "after all the vessels and ornaments of the temple were supplied, there was enough gold and silver left to raise and complete another temple without other material whatsoever." All the treasure was thrown into Lake Titicaca to save it from the Spaniards. Ten of them were drowned in 1541, while hunting for it. Titicaca guards its secrets well. The approach to the temple was a very complicated structure known as "the place where people lose themselves." The pilgrims, after much fasting on the sacred ground of the island, were allowed to pass barefoot through the first gate above, the "door of the puma," puma-puncu. After more fasting, they might go down through the second gate, the "door of the humming-bird," kenti-puncu, so called from feathers of humming-birds plastered over its inner side. They were especially honored by the Incas, colored like the rainbow emblem. After more ceremonies, the pilgrims were allowed to go through the "door of hope," pillco-puncu, covered with feathers of the bird of hope. Those who had come so far might now worship the holy cliff, but they were not allowed to touch the face of the cliff nor to walk upon it. Sacrifices to it were small children, whose heads the priests cut off with sharp stones. The sacrificial stone of the Island of Titicaca still remains, rubbed smooth by the iron tooth of time, split into three pieces by a thunderbolt. So does the queen's meadow below the terraces, where the carmine, yellow, and white cantut, flor-del-Inca, recalls the blazing color of other days, when fruit ripened here twelve thousand feet above the sea, and maize of which Sun-virgins made the bread of sacrifice. Beyond, is the island called Coati, consecrated to the Moon, where her temple used to be. The life-size statue of a woman was found here, gold in the upper half, silver in the lower. The Fountain of the Incas still gushes two streams of clear water. "A stolid Indian sits watching it pour away, never dreaming whence it comes, as no one, indeed, knows." |