CHAPTER IV

THE ANIMALS AND BIRDS

The kangaroo — The koala — The bulldog ant — Some quaint and delightful birds — The kookaburra — Cunning crows and cockatoo.

Australia

has most curious animals, birds, and flowers. This is due to the fact

that it is such an old, old place, and has been cut off so long from

the rest of the world. The types of animals that lived in Europe long

before Rome was built, before the days, indeed, of the Egyptian

civilization, animals of which we find traces in the fossils of very

remote periods — those are the types living in Australia to-day. They

belong to the same epoch as the mammoth and the great flying lizards

and other creatures of whom you may learn something in museums. Indeed,

Australia, as regards its fauna, may be considered as a museum, with

the animals of old times alive instead of in skeleton form. The

kangaroo is always taken as a type of Australian animal life. When an

Australian cricket team succeeds in vanquishing in a Test Match an

English one (which happens now and again), the comic papers may be

always expected to print a picture of a lion looking sad and sorry, and

a kangaroo proudly elate. The kangaroo, like practically all Australian

animals, is a marsupial, carrying its young about in a pouch after

their birth until they reach maturity. The kangaroo’s forelegs are very

small; its hind legs and its tail are immensely powerful, and these it

uses for progression, rushing with huge hops over the country. There

are very many animals which may be grouped as kangaroos, from the tiny

kangaroo rat, about the size of an English water-rat, to the huge red

kangaroo, which is over six feet high and about the weight of a sucking

calf. The kangaroo is harmless and inoffensive as a rule, but it can

inflict a dangerous kick with its hind legs, and when pursued by dogs

or men and cornered, the “old man” kangaroo will sometimes fight for

its life. Its method is to take a stand in a water-hole or with its

back to a tree, standing on its hind legs and balanced on its tail.

When a dog approaches it is seized in the kangaroo’s forearms and held

under water or torn to pieces. Occasionally men’s lives have been lost

through approaching incautiously an old man kangaroo. The

kangaroo’s method of self-defence has been turned to amusing account by

circus-proprietors. The “boxing kangaroo” was at one time quite a

common feature at circuses and music-halls. A tame kangaroo would have

its forefeet fitted with boxing-gloves. Then when lightly punched by

its trainer, it would, quite naturally, imitate the movements of the

boxer, fending off blows and hitting out with its forelegs. One boxing

kangaroo I had a bout with was quite a clever pugilist. It was very

difficult to hit the animal, and its return blows were hard and well

directed. The

different sorts of kangaroo you may like to know. There is the kangaroo

rat, very small; the “flying kangaroo,” a rare animal of the squirrel

species, but marsupial, which lives in trees; the wallaby, the

wallaroo, the paddy-melon (medium varieties of kangaroo); the grey and

the red kangaroo, the last the biggest and finest of the species. The

kangaroo, as I have said, is not of much use for meat. Its flesh is

very dark and rank, something like that of a horse. However, chopped up

into a fine sausage-meat, with half its weight of fat bacon, kangaroo

flesh is just eatable. The tail makes a very rich soup. The skin of the

kangaroo provides a soft and pliant leather which is excellent for

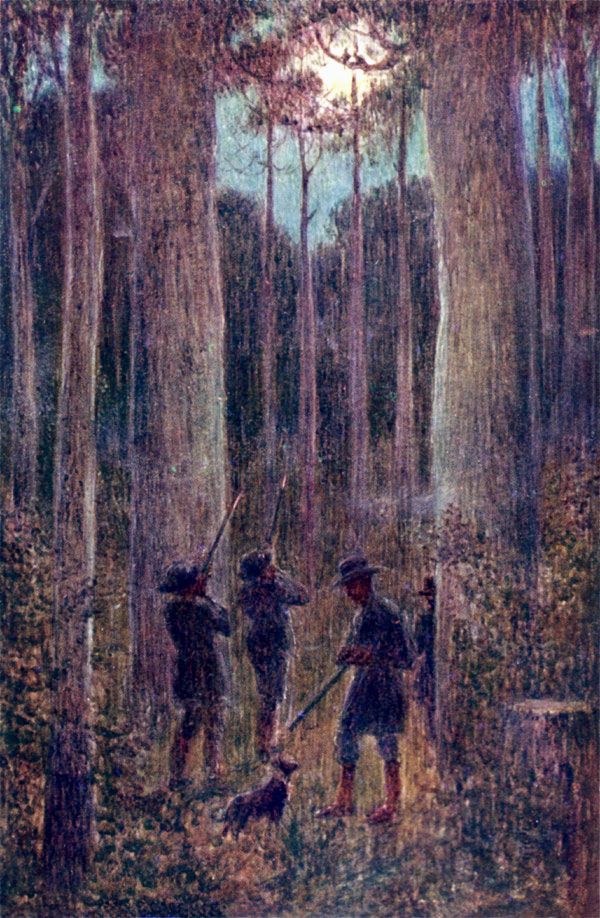

shoes. Kangaroo furs are also of value for rugs and overcoats.  The Australian forest at night - "mooning" Opossums. The Australian forest at night - "mooning" Opossums.Of

tree-inhabiting animals the chief in Australia is the ’possum (which is

not really an opossum, but is somewhat like that American rodent, and

so got its name), and the koala, or native bear. Why this little animal

was called a “bear” it is hard to say, for it is not in the least like

a bear. It is about the size of a very large and fat cat, is covered

with a very thick, soft fur, and its face is shaped rather like that of

an owl, with big saucer-eyes. The

koala is the quaintest little creature imaginable. It is quite

harmless, and only asks to be let alone and allowed to browse on

gum-leaves. Its flesh is uneatable except by an aboriginal or a victim

to famine. Its fur is difficult to manipulate, as it will not lie flat,

so the koala should have been left in peace. But its confiding and

somewhat stupid nature, and the senseless desire of small boys and

“children of larger growth” to kill something wild just for the sake of

killing, has led to the koala being almost exterminated in many places.

Now it is protected by the law, and may get back in time to its old

numbers. I hope so. There is no more amusing or pretty sight than that

of a mother koala climbing sedately along a gum-tree limb, its young

ones riding on it pick-a-back, their claws dug firmly into its soft fur. The

’possum is much hunted for its fur. The small black ’possum found in

Tasmania and in the mountainous districts is the most valuable, its fur

being very close and fine. Dealers in skins will sometimes dye the grey

’possum’s skin black and trade it off as Tasmanian ’possum. It is a

trick to beware of when buying furs. Bush lads catch the ’possum with

snares. Finding a tree, the scratched bark of which tells that a

’possum family lives upstairs in one of its hollows, they fix a noose

to the tree. The ’possum, coming down at night to feed or to drink, is

caught in the noose. Another way of getting ’possum skins is to shoot

the little creatures on moonlight nights. (The ’possum is nocturnal in

its habits, and sleeps during the day.) When there is a good moon the

’possums may be seen as they sit on the boughs of the gum-trees, and

brought down with a shot-gun. Besides

its human enemies, the ’possum has the ’goanna (of which more later) to

contend with. The ’goanna — a most loathsome-looking lizard — can climb

trees, and is very fond of raiding the ’possum’s home when the young

are there. Between the men who want its coat and the ’goannas who want

its young the ’possum is fast being exterminated. Two

other characteristic Australian animals you should know about. The

wombat is like a very large pig; it lives underground, burrowing vast

distances. The wombat is a great nuisance in districts where there are

irrigation canals; its burrows weaken the banks of the water-channels,

and cause collapses. The dugong is a sea mammal found on the north

coast of Australia. It is said to be responsible for the idea of the

mermaid. Rising out of the water, the dugong’s figure has some

resemblance to that of a woman. Then

there is the bunyip — or, rather, there isn’t the bunyip, so far as we

know as yet. The bunyip is the legendary animal of Australia. It is

supposed to be of great size — as big as a bullock — and of terrible

ferocity. The bunyip is represented as living in lakes and marshes, but

it has never been seen by any trustworthy observer. The blacks believe

profoundly in the bunyip, and white children, when very young, are

scared with bunyip tales. There may have been once an animal answering

to its description in Australia; if so, it does not seem to have

survived. In

Tasmania, however, are found, though very rarely, two savage and

carnivorous marsupials called the Tasmanian tiger and the Tasmanian

devil. The tiger is almost as large as the female Bengal tiger, and has

a few little stripes near its tail, from which fact it gets its name.

The Tasmanian tiger will create fearful havoc if it gets among sheep,

killing for the sheer lust of killing. At one time a price of £100 was

put on the head of the Tasmanian tiger. As settlement progressed it

became rarer and rarer, and I have not heard of one having been seen

for some years. The Tasmanian devil is a marsupial somewhat akin to the

wild cat, and of about the same size. It is very ferocious, and has

been known to attack man, springing on him from a tree branch. The

Tasmanian devil is likewise becoming very rare. The

existence of these two animals in Tasmania and not in Australia shows

that that island has been a very long time separated from the mainland. Australia

is very well provided with serpents — rather too well provided — and

the Bush child has to be careful in regard to putting his hand into

rabbit burrows or walking barefoot, as there are several varieties of

venomous snake. But the snakes are not at all the great danger that

some imagine. You might live all your life in Australia and never see

one; but in a few country parts it has been found necessary to enclose

the homesteads on the stations with snake-proof wire-fencing, so as to

make some place of safety in which young children may play. The most

venomous of Australian snakes are the death-adder, fortunately a very

sluggish variety; the tiger-snake, a most fierce serpent, which, unlike

other snakes, will actually turn and pursue a man if it is wounded or

angered; the black snake, a handsome creature with a vivid scarlet

belly; and the whip-snake, a long, thin reptile, which may be easily

mistaken for a bit of stick, and is sometimes picked up by children.

But no Australian snake is as deadly as the Indian jungle snakes, and

it is said that the bite of no Australian snake can cause death if the

bite has been given through any cloth. So the only real danger is in

walking through the Bush barefooted, or putting the hand into holes

where snakes may be lurking. Some

of the non-venomous snakes of Australia are very handsome, the green

tree-snake and the carpet-snake (a species of python) for examples. The

carpet-snake is occasionally kept in the house or in the barn to

destroy mice and other small vermin. Lizards

in great variety are found in Australia, the chief being one

incorrectly called an iguana, which colloquial slang has changed to

’goanna. The ’goanna is an altogether repulsive creature. It feasts on

carrion, on the eggs of birds, on birds themselves, on the young of any

creature. Growing to a great size — I have seen one 9 feet long and as

thick in the body as a small dog — the ’goanna looks very dangerous,

and it will bite a man when cornered. Though not venomous in the strict

sense of the word, the ’goanna’s bite generally causes a festering

wound on account of the loathsome habits of the creature. The

Jew-lizard and the devil-lizard are two other horrid-looking denizens

of the Australian forest, but in their cases an evil character does not

match an evil face, for they are quite harmless. Spiders

are common, but there is, so far as I know, only one dangerous one — a

little black spider with a red spot on its back. Large spiders, called

(incorrectly) tarantulas, credited by some with being poisonous, come

into the houses. But they are really not in any way dangerous. I knew a

man who used to keep tarantulas under his mosquito-nets so that they

might devour any stray mosquitoes that got in. The example is hardly

worth following. The Australian tarantula, though innocent of poison,

is a horrible object, and would, I think, give you a bad fright if it

flopped on to your face. Australia

is rich in ants. There is one specially vicious ant called the bulldog

ant, because of its pluck. Try to kill the bulldog ant with a stick,

and it will face you and try to bite back until the very last gasp,

never thinking of running away. The bulldog ant has a liking for the

careless picnicker, whom she — the male ant, like the male bee, is not

a worker — bites with a fierce energy that suggests to the victim that

his flesh is being torn with red-hot pincers. I have heard it said that

but for the fact that Australia is so large an island, a great

proportion of its population would by this time have been lost through

bounding into the surrounding sea when bitten by bulldog ants. It is

wise when out for a picnic in Australia to camp in some spot away from

ant-beds, for the ant, being such an industrious creature, seems to

take a malicious delight in spoiling the day for pleasure-seekers. In

one respect, the ant, unwillingly enough, contributes to the pleasure

and amusement of the Australian people. In the dry country it would not

be possible to keep grass lawns for tennis. But an excellent substitute

has been found in the earth taken from ant-beds. This earth, which has

been ground fine by the industrious little insects, makes a beautifully

firm tennis-court. It

is not possible to leave the ant without mention of the termite, or

white ant, which is very common and very mischievous in most parts of

Australia. A colony of termites keeps its headquarters underground, and

from these headquarters it sends out foraging expeditions to eat up all

the wood in the neighbourhood. If you build a house in Australia, you

must be very careful indeed that there is no possibility of the

termites being able to get to its timbers. Otherwise the joists will be

eaten, the floors eaten, even the furniture eaten, and one day

everything that is made of wood in the house will collapse. All the

mischief, too, will have been concealed until the last moment. A wooden

beam will look to be quite sound when really its whole heart has been

eaten out by the termites. Nowadays the whole area on which a house is

to be raised is covered with cement or with asphalt, and care taken

that no timber joists are allowed to touch the earth and thus give

entry to the termites. Fortunately, these destructive insects cannot

burrow through brick or stone. In

the Northern Territory there are everywhere gigantic mounds raised by

these termites, long, narrow, high, and always pointing due north and

south. You can tell infallibly the points of the compass from the

mounds of this white ant, which has been called the “meridian termite.” Australia

has a wild bee of her own (of course, too, there are European bees

introduced by apiarists, distilling splendid honey from the wild

flowers of the continent). The aborigines had an ingenious way of

finding the nests of the wild bee. They would catch a bee, preferably

at some water-hole where the bees went to drink, and fix to its body a

little bit of white down. The bee would be then released, and would fly

straight for home, and the keen-eyed black would be able to follow its

flight and discover the whereabouts of its hive — generally in the

hollow of a tree. The Australian black, having found a hive, would kill

the bees with smoke and then devour the whole nest, bees, honeycomb,

and honey. Australian

birds are very numerous and very beautiful. The famous bird-of-paradise

is found in several varieties in Papua and other islands along

Australia’s northern coast. The bird-of-paradise was threatened with

extinction on account of the demand for its plumes for women’s hats. So

the Australian Government has recently passed legislation to protect

this most beautiful of all birds, which on the tiniest of bodies

carries such wonderful cascades of plumage, silver white in some cases,

golden brown in others.  A sheep drover. A sheep drover.Some

very beautiful parrots flash through the Australian forest. It would

not be possible to tell of all of them. The smallest, which is known as

the grass parrakeet, or “the love-bird,” is about the size of a

sparrow. I notice it in England carried around by gipsies and trained

to pick out a card which “tells you your fortune.” From that tiny

little green bird the range of parrots runs up to huge fowl with

feathers of all the colours of the rainbow. There are two fine

cockatoos also in Australia — the white with a yellow crest, and the

black, which has a beautiful red lining to its sable wings. A flock of

black cockatoos in flight gives an impression of a sunset cloud, its

under surface shot with crimson. Cockatoos

can be very destructive to crops, especially to maize, so the farmers

have declared war upon them. The birds seem to be able to hold their

own pretty well in this campaign, for they are of wonderful cunning.

When a crowd of cockatoos has designs on a farmer’s maize-patch, the

leader seems to prospect the place thoroughly; he acts as though he

were a general, providing a safe bivouac for an army; he sets sentinels

on high trees commanding a view of all points of danger. Then the flock

of cockatoos settles on the maize and gorges as fast as it can. If the

farmer or his son tries to approach with a gun, a sentinel cockatoo

gives warning and the whole flock clears out to a place of safety. As

soon as the danger is over they come back to the feast. Even

more cunning is the Australian crow. It is a bird of prey and perhaps

the best-hated bird in the world. An Australian bushman will travel a

whole day to kill a crow. For he has, at the time when the sheep were

lambing, or when, owing to drought, they were weak, seen the horrible

cruelties of the crow. This evil bird will attack weak sheep and young

lambs, tearing out their eyes and leaving them to perish miserably.

There have even been terrible cases where men lost in the Bush and

perishing of thirst have been attacked by crows and have been found

still alive, but with their eyes gone. It

is no wonder that there is a deadly feud between man and crow. But the

crow is so cunning as to be able to overmatch man’s superior strength.

A crow knows when a man is carrying a gun, and will keep out of range

then; if a man is without a gun the crow will let him approach quite

near. One can never catch many crows in the same district with the same

device; they seem to learn to avoid what is dangerous. Very rarely can

they be poisoned, no matter how carefully the bait is prepared. Bushmen

tell all sorts of stories of the cunning of the crow. One is that of a

man who suffered severely from a crow’s depredations on his chickens.

He prepared a poisoned bait and noticed the bird take it, but not

devour it; that crow carefully took the poisoned tit-bit and put it in

front of the man’s favourite dog, which ate it, and was with difficulty

saved from death! Another story is that of a man who thought to get

within reach of a crow by taking out a gun, lying down under a tree,

and pretending to be dead. True enough, the crow came up and hopped

around, as if waiting for the man to move, and so to see if he were

really dead. After awhile, the crow, to make quite sure, perched on a

branch above the man’s head and dropped a piece of twig on to his face!

It was at this stage that the man decided to be alive, and, taking up

his gun, shot the crow. There

may be some exaggeration in the bushmen’s tales of the crow’s cunning,

but there is quite enough of ascertained fact to show that the bird is

as devilish in its ingenuity as in its cruelty. In most parts of

Australia there is a reward paid for every dead crow brought into the

police offices. Still, in spite of constant warfare, the bird holds its

own, and very rarely indeed is its nest discovered — a signal proof of

its precautions against the enmity of man. To

turn to a more pleasant type of feathered animal. On the whole, the

most distinctly Australian bird is the kookaburra, or “laughing

jackass.” (A picture of two kookaburras are at the beginning of this

volume. They were drawn for me by a very clever Australian

black-and-white artist, Mr. Norman Lindsay.) The kookaburra is about

the size of an owl, of a mottled grey colour. Its sly, mocking eye

prepares you for its note, which is like a laugh, partly sardonic,

partly rollicking. The kookaburra seems to find much grim fun in this

world, and is always disturbing the Bush quiet with its curious

“laughter.” So near in sound to a harsh human laugh is the kookaburra’s

call that there is no difficulty in persuading new chums that the bird

is deliberately mocking them. The kookaburra has the reputation of

killing snakes; it certainly is destructive to small vermin, so its

life is held sacred in the Bush. And very well our kookaburra knows the

fact. As he sits on a fence and watches you go past with a gun, he will

now and again break out into his discordant “laugh” right in your face. The

Australian magpie, a black-and-white bird of the crow family, is also

“protected,” as it feeds mainly on grubs and insects, which are

nuisances to the farmer. The magpie has a very clear, well-sustained

note, and to hear a group of them singing together in the early morning

suggests a fine choir of boys’ voices. They will tell you in Australia

that the young magpie is taught by its parents to “sing in tune” in

these bird choirs, and is knocked off the fence at choir practice if it

makes a mistake. You may believe this if you wish to. I don’t. But it

certainly is a fact that a group of magpies will sing together very

sweetly and harmoniously. One

could not exhaust the list of Australian birds in even a big book. But

a few more call for mention. There is the emu, like an ostrich, but

with coarse wiry hair. The emu does damage on the sheep-runs by

breaking down the wire fences. (Some say the emu likes fencing wire as

an article of diet; but that is an exaggeration founded on the fact

that, like all great birds, it can and does eat nails, pebbles, and

other hard substances, which lodge in its gizzard and help it to digest

its food.) On account of its mischievous habit of breaking fences the

emu is hunted down, and is now fast dwindling. In Tasmania it is

altogether extinct. Another danger to its existence is that it lays a

very handsome egg of a dark green colour. These eggs are sought out for

ornaments, and the emu’s nest, built in the grass of the plain (for the

emu cannot fly nor climb trees), is robbed wherever found. The

brush turkey of Australia is strange in that it does not take its

family duties at all seriously. The bird does not hatch out its eggs by

sitting on them, but builds a mound of decaying vegetation over the

eggs, and leaves them to come out with the sun’s heat. The

brolga, or native companion, is a handsome Australian bird of the crane

family. It is of a pretty grey colour, with red bill and red legs. The

brolga has a taste for dancing; flocks of this bird may be seen

solemnly going through quadrilles and lancers — of their own invention

— on the plains. Another

strange Australian bird is called the bower-bird, because when a

bower-bird wishes to go courting he builds in the Bush a little

pavilion, and adorns it with all the gay, bright objects he can — bits

of rag or metal, feathers from other birds, coloured stones and

flowers. In this he sets himself to dancing until some lady bower-bird

is attracted, and they set up housekeeping together. The bower-bird is

credited with being responsible for the discovery of a couple of

goldfields, the birds having picked up nuggets for their bowers, these,

discovered by prospectors, telling that gold was near. If

the bower-bird wishes for wedding chimes to grace his picturesque

mating, another bird will be able to gratify the wish — the bell-bird

which haunts quiet, cool glens, and has a note like a bell, and yet

more like the note of one of those strange hallowed gongs you hear from

the groves of Eastern temples. Often riding through the wild Australian

Bush you hear the chimes of distant bells, hear and wonder until you

learn that the bell-bird makes the clear, sweet music. One

more note about Australian nature life. In the summer the woods are

full of locusts (cicadæ), which jar the air with their harsh note. The

locust season is always a busy one for the doctors. The Australian

small boy loves to get a locust to carry in his pocket, and he has

learned, by a little squeezing, to induce the unhappy insect to “strike

up,” to the amusing interruption of school or home hours. Now, to get a

locust it is necessary to climb a tree, and Australian trees are hard

to climb and easy to fall out of. So there are many broken limbs during

the locust season. They represent a quite proper penalty for a cruel

and unpleasant habit. |