CHAPTER III

THE NATIVES

A dwindling race; their curious weapons — The Papuan tree-dwellers — The cunning witch-doctors.

The

natives of Australia were always few in number. The conditions of the

country secured that Australia, kept from civilization for so long, is

yet the one land of the world which, whilst capable of great production

with the aid of man’s skill, is in its natural state hopelessly

sterile. Australia produced no grain of any sort naturally; neither

wheat, oats, barley nor maize. It produced practically no edible fruit,

excepting a few berries, and one or two nuts, the outer rind of which

was eatable. There were no useful roots such as the potato, the turnip,

or the yam, or the taro. The native animals were few and just barely

eatable, the kangaroo, the koala (or native bear) being the principal

ones. In birds alone was the country well supplied, and they were more

beautiful of plumage than useful as food. Even the fisheries were

infrequent, for the coast line, as you will see from the map, is

unbroken by any great bays, and there is thus less sea frontage to

Australia than to any other of the continents, and the rivers are few

in number. Where the land inhabited by savages is poor in

food-supply their number is, as a rule, small and their condition poor.

It is not good for a people to have too easy times; that deprives them

of the incentive to work. But also it is not good for people who are

backward in civilization to be kept to a land which treats them too

harshly; for then they never get a fair chance to progress in the scale

of civilization. The people of the tropics and the people near the

poles lagged behind in the race for exactly opposite but equally

powerful reasons. The one found things too easy, the other found things

too hard. It was in the land between, the Temperate Zone, where, with

proper industry, man could prosper, that great civilizations grew up. The

Australian native had not much to complain of in regard to his climate.

It was neither tropical nor polar. But the unique natural conditions of

his country made it as little fruitful to an uncivilized inhabitant as

was Lapland. When Captain Cook landed at Botany Bay probably there were

not 500,000 natives in all Australia. And if the white man had not

come, there probably would never have been any progress among the

blacks. As they were then they had been for countless centuries, and in

all likelihood would have remained for countless centuries more. They

had never, like the Chinese, the Hindus, the Peruvians, the Mexicans,

evolved a civilization of their own. There was not the slightest sign

that they would be able to do so in the future. If there was ever a

country on earth which the white man had a right to take on the ground

that the black man could never put it to good use, it was Australia. Allowing

that, it is a pity to have to record that the early treatment of the

poor natives of Australia was bad. The first settlers to Australia had

learned most of the lessons of civilization, but they had not learned

the wisdom and justice of treating the people they were supplanting

fairly. The officials were, as a rule, kind enough; but some classes of

the new population were of a bad type, and these, coming into contact

with the natives, were guilty of cruelties which led to reprisals and

then to further cruelties, and finally to a complete destruction of the

black people in some districts. In Tasmania, for instance, where the

blacks were of a fine robust type, convicts in the early days, escaping

to the Bush, by their cruelties inflamed the natives to hatred of the

white disturbers, and outrages were frequent. The state of affairs got

to be so bad that the Government formed the idea of capturing all the

natives of Tasmania and putting them on a special reserve on Tasman

Peninsula. That was to be the black man’s part of the country, where no

white people would be allowed. The help of the settlers was enlisted,

and a great cordon was formed around the whole island, as if it were to

be beaten for game. The cordon gradually closed in on Tasman Peninsula

after some weeks of “beating” the forests. It was found, then, that one

aboriginal woman had been captured, and that was all. Such a result

might have been foreseen. Tasmania is about as large as Scotland. Its

natural features are just as wild. The cordon did not embrace 2,000

settlers. The idea of their being able to drive before them a whole

native race familiar with the Bush was absurd. After that the old

conditions ruled in Tasmania. Blacks and whites were in constant

conflict, and the black race quickly perished. To-day there is not a

single member of that race alive, Truganini, its last representative,

having died about a quarter of a century ago. On the mainland of

Australia many blacks still survive; indeed, in a few districts of the

north, they have as yet barely come into contact with the white race. A

happier system in dealing with them prevails. The Government are

resolute that the blacks shall be treated kindly, and aboriginal

reserves have been formed in all the States. One hears still of acts of

cruelty in the back-blocks (as the far interior of Australia is

called), but, so far as the Government can, it punishes the offenders.

In several of the States there is an official known as the Protector of

the Aborigines, and he has very wide powers to shield these poor blacks

from the wickedness of others, and from their own weakness. In the

Northern States now, the chief enemies of the blacks are Asiatics from

the pearl-shelling fleets, who land in secret and supply the blacks

with opium and drink. When the Commonwealth Navy, now being

constructed, is in commission, part of its duty will be to patrol the

northern coast and prevent Asiatics landing there to victimize the

blacks. The official statistics of the Commonwealth reported, in regard to the aborigines, in the year 1907: “In

Queensland, South Australia, and Western Australia, on the other hand,

there are considerable numbers of natives still in the ‘savage’ state,

numerical information concerning whom is of a most unreliable nature,

and can be regarded as little more than the result of mere guessing.

Ethnologically interesting as is this remarkable and rapidly

disappearing race, practically all that has been done to increase our

knowledge of them, their laws, habits, customs, and language, has been

the result of more or less spasmodic and intermittent effort on the

part of enthusiasts either in private life or the public service.

Strange to say, an enumeration of them has never been seriously

undertaken in connection with any State census, though a record of the

numbers who were in the employ of whites, or living in contiguity to

the settlements of whites, has usually been made. As stated above,

various guesses at the number of aboriginal natives at present in

Australia have been made, and the general opinion appears to be that

150,000 may be taken as a rough approximation to the total. It is

proposed to make an attempt to enumerate the aboriginal population of

Australia in connection with the first Commonwealth Census to be taken

in 1911.” A very primitive savage was the Australian aboriginal. He

had no architecture, but in cold or wet weather built little

break-winds, called mia-mias. He had no weapons of steel or any other

metal. His spears were tipped with the teeth of fish, the bones of

animals, and with roughly sharpened flints. He had no idea of the use

of the bow and arrow, but had a curious throwing-stick, which, working

on the principle of a sling, would cast a missile a great distance.

These were his weapons — rough spears, throwing-sticks, and clubs

called nullahs, or waddys. (I am not sure that these latter are

original native words. The blacks had a way of picking up white men’s

slang and adding it to their very limited vocabulary; thus the evil

spirit is known among them as the “debbil-debbil.”) Another weapon the

aboriginal had, the boomerang, a curiously curved missile stick which,

if it missed the object at which it was aimed, would curve back in the

air and return to the feet of the thrower; thus the black did not lose

his weapon. The boomerang shows an extraordinary knowledge of the

effects of curves on the flight of an object; it is peculiar to the

Australian natives, and proves that they had skill and cunning in some

respects, though generally low in the scale of human races. The

Australian aboriginals were divided into tribes, and these tribes, when

food supplies were good, amused themselves with tribal warfare. From

what can be gathered, their battles were not very serious affairs.

There was more yelling and dancing and posing than bloodshed. The

braves of a tribe would get ready for battle by painting themselves

with red, yellow, and white clay in fantastic patterns. They would then

hold war-dances in the presence of the enemy; that, and the exchange of

dreadful threats, would often conclude a campaign. But sometimes the

forces would actually come to blows, spears would be thrown, clubs

used. The wounds made by the spears would be dreadfully jagged, for

about half a yard of the end of the spear was toothed with bones or

fishes’ teeth. But the black fellows’ flesh healed wonderfully. A wound

that would kill any European the black would plaster over with mud, and

in a week or so be all right. Duels between individuals were not

uncommon among the natives, and even women sometimes settled their

differences in this way. A common method of duelling was the exchange

of blows from a nullah. One party would stand quietly whilst his

antagonist hit him on the head with a club; then the other, in turn,

would have a hit, and this would be continued until one party dropped.

It was a test of endurance rather than of fighting power. The women

of the aboriginals were known as gins, or lubras, the children as

picaninnies — this last, of course, not an aboriginal name. The women

were not treated very well by their lords: they had to do all the

carrying when on the march. At mealtimes they would sit in a row behind

the men. The game — a kangaroo, for instance — would be roughly roasted

at the camp fire with its fur still on. The men would devour the best

portions and throw the rest over their shoulders to the waiting women. Fish

was a staple article of diet for the Australian natives. Wherever there

were good fishing-places on the coast or good oyster-beds powerful

tribes were camped, and on the inland rivers are still found weirs

constructed by the natives to trap fish. So far as can be ascertained,

the Australian native was rarely if ever a cannibal. His neighbours in

the Pacific Ocean were generally cannibals. Perhaps the scanty

population of the Australian continent was responsible for the absence

of cannibalism; perhaps some ethical sense in the breasts of the

natives, who seem to have always been, on the whole, good-natured and

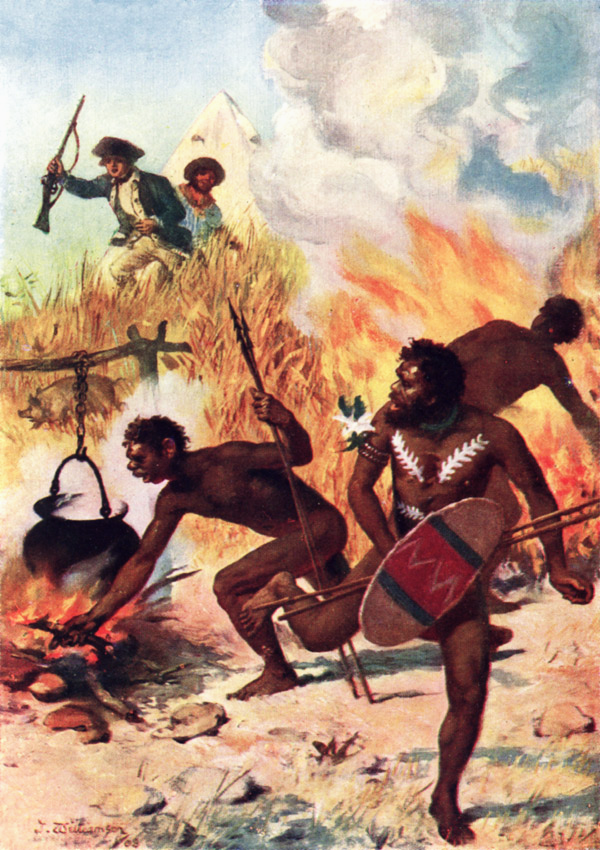

little prone to cruelty.  The Australian natives in Captain Cook's time. The Australian natives in Captain Cook's time.The

religious ideas of these natives were very primitive. They believed

strongly in evil spirits, and had various ceremonial dances and

practices of witchcraft to ward off the influence of these. But they

had little or no conception of a Good Spirit. Their idea of future

happiness was, after they had come into contact with the whites: “Fall

down black fellow, jump up white fellow.” Such an idea of heaven was,

of course, an acquired one. What was their original notion on the

subject is not at all clear. The Red Indians of America had a very

definite idea of a future happy state. The aboriginals of Australia do

not seem to have been able to brighten their poor lives with such a

hope. Various books have been written about the folklore of the

Australian aboriginals, but most of the stories told as coming from the

blacks seem to me to have a curious resemblance to the stories of white

folk. A legend about the future state, for instance, is just Bunyan’s

“Pilgrim’s Progress” put crudely to fit in with Australian conditions.

I may be quite wrong in this, but I think that most of the folk-stories

coming from the natives are just their attempts to imitate white-man

stories, and not original ideas of their own. The conditions or life in

Australia for the aboriginal were so harsh, the struggle for existence

was so keen, that he had not much time to cultivate ideas. Life to him

was centred around the camp-fire, the baked ’possum, and a few crude

tribal ceremonies. Usually the Australian black is altogether spoilt

by civilization. He learns to wear clothes, but he does not learn that

clothes need to be changed and washed occasionally, and are not

intended for use by day and night. He has an insane veneration for the

tall silk hat which is the badge of modern gentility, and, given an old

silk hat, he will never allow it off his head. He quickly learns to

smoke and to drink, and, when he comes into contact with the Chinese,

to eat opium. He cannot be broken into any steady habits of industry,

but where by wise kindness the black fellow has been kept from the

vices of civilization he is a most engaging savage. Tall, thin,

muscular, with fine black beard and hair and a curiously wide and

impressive forehead, he is not at all unhandsome. He is capable of

great devotion to a white master, and is very plucky by daylight,

though his courage usually goes with the fall of night. He takes to a

horse naturally, and some of the finest riders in Australia are black

fellows. An attempt is now being made to Christianize the Australian

blacks. It seems to prosper if the blacks can be kept away from the

debasing influence of bad whites. They have no serious vices of their

own, very little to unlearn, and are docile enough. In some cases black

children educated at the mission schools are turning out very well.

But, on the other hand, there are many instances of these children

conforming to the habits of civilization for some years and then

suddenly feeling “the call of the wild,” and running away into the Bush

to join some nomad tribe. It is not possible to be optimistic about

the future of the Australian blacks. The race seems doomed to perish.

Something can be done to prolong their life, to make it more pleasant;

but they will never be a people, never take any share in the

development of the continent which was once their own. A quite

different type of native comes under the rule of the Australian

Commonwealth — the Papuan. Though Papua, or New Guinea, as it was once

called, is only a few miles from the north coast of Australia, its race

is distinct, belonging to the Polynesian or Kanaka type, and resembling

the natives of Fiji and Tahiti. Papua is quite a tropical country,

producing bananas, yams, taro, sago, and cocoa-nuts. The natives,

therefore, have always had plenty of food, and they reached a higher

stage of civilization than the Australian aborigines. But their food

came too easily to allow them to go very far forward. “Civilization is

impossible where the banana grows,” some observer has remarked. He

meant that since the banana gave food without any culture or call on

human energy, the people in banana-growing countries would be lazy, and

would not have the stimulus to improve themselves that is necessary for

progress. To get a good type of man he must have the need to work. The

Papuan, having no need of industry, amused himself with head-hunting as

a national sport. Tribes would invade one another’s districts and fight

savage battles. The victors would eat the bodies of the vanquished, and

carry home their heads as trophies. A chief measured his greatness by

the number of skulls he had to adorn his house. Since the British

came to Papua head-hunting and cannibalism have been forbidden. But all

efforts to instil into the minds of the Papuan a liking for work have

so far failed. So the condition of the natives is not very happy. They

have lost the only form of exercise they cared for, and sloth, together

with contact with the white man, has brought to them new and deadly

diseases. Several missionary bodies are working to convert the Papuan

to Christianity, and with some success. The Papuan builds houses and

temples. His tree-dwellings are very curious. They are built on

platforms at the top of lofty palm-trees. Probably the Papuan first

designed the tree-dwelling as a refuge from possible enemies. Having

climbed up to his house with the aid of a rope ladder and drawn the

ladder up after him, he was fairly safe from molestation, for the long,

smooth, branchless trunks of the palm-trees do not make them easy to

scale. In time the Papuan learned the advantages of the tree-dwelling

in marshy ground, and you will find whole villages on the coast built

of trees. Herodotus states of the ancient Egyptians that in some parts

they slept on top of high towers to avoid mosquitoes and the malaria

that they brought. The Papuan seems to have arrived at the same idea. Sorcery

is a great evil among the Papuans. In every village almost, some crafty

man pretends to be a witch and to have the power to destroy those who

are his enemies. This is a constant thorn in the side of the Government

official and the missionary. The poor Papuan goes all his days beset by

the Powers of Darkness. The sorcerer, the “pourri-pourri” man, can

blast him and his pigs, crops, family (that is the Papuan order of

valuation) at will. The sorcerer is generally an old man. He does not,

as a rule, deck himself in any special garb, or go through public

incantations, as do most savage medicine-men. But he hints and

threatens, and lets inference take its course, till eventually he

becomes a recognized power, feared and obeyed by all. Extortion, false

swearing, quarrels and murders, and all manner of iniquity, follow in

his train. No native but fears him, however complete the training and

education of civilization. For the Papuan never thinks of death,

plague, pestilence or famine as arising from natural causes. Every

little misfortune (much more every great one) is credited to a

“pourri-pourri” or magic. The Papuan, when he comes “under the Evil

Eye” of the witch-doctor, will wilt away and die, though, apparently,

he has nothing at all the matter with him; and since Europeans are apt

to suffer from malarial fever in Papua, the witch-doctors are prompt to

put this down to their efforts, and so persuade the natives that they

have power even over Europeans. A gentleman who was a resident

magistrate in Papua tells an amusing tale of how one witch-doctor was

very properly served. “A village constable of my acquaintance, wearied

with the attentions of a magician of great local repute, who had worked

much harm with his friends and relations, tied him up with rattan

ropes, and sank him in 20 feet of water against the morning. He argued,

as he explained at his trial for murder, ‘If this man is the genuine

article, well and good, no harm done. If he is not — well, it’s a good

riddance!’ On repairing to the spot next morning, and pulling up his

night-line, he found that the magician had failed to ‘make his magic

good,’ and was quite dead. The constable’s punishment was twelve

months’ hard labour. It was a fair thing to let him off easily, as in

killing a witch-doctor he had really done the community a service.” The

future of the Papuan is more hopeful than that of the Australian

aboriginal, and he may be preserved in something near to his natural

state if means can be found to make him work. |