| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| CAPE OF THE WOMAN'S SWORD1 DOWN

in the Province of Higo are a group of large islands, framing with the

mainland

veritable little inland seas, deep bays, and narrow channels. The whole

of this

is called Amakusa. There are a village called Amakusa mura, a sea known

as

Amakusa umi, an island known as Amakusa shima, and the Cape known as

Joken

Zaki, which is the most prominent feature of them all, projecting into

the

Amakusa sea. History

relates that in the year 1577 the Daimio of the province issued an

order that

every one under him was to become a Christian or be banished. During

the next century this decree was reversed; only, it was ordered that

the

Christians should be executed. Tens of thousands of Christianised heads

were

collected and sent for burial to Nagasaki, Shimabara and Amakusa. This

— repeated from Murray — has not much to do with my story.

After all, it

is possible that at the time the Amakusa people became Christian the

sword in

question, being in some temple, was with the gods cast into the sea,

and

recovered later by a coral or pearl diver in the Bunroku period, which

lasted

from 1592 to 1596. A history would naturally spring from a sword so

recovered.

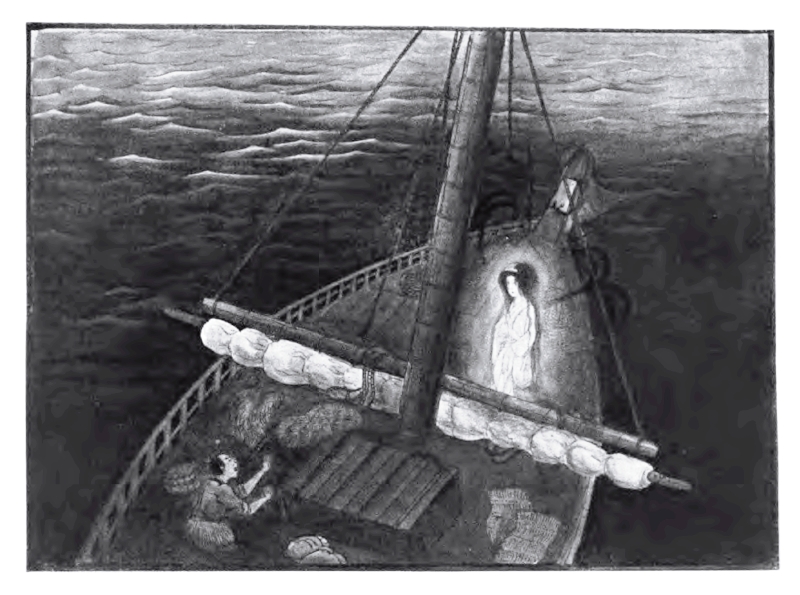

But to the story. The Cape of Joken Zaki (the Woman's Sword Cape) was not always so called. In former years, before the Bunroku period, it had been called Fudozaki (Fudo is the God of Fierceness, always represented as surrounded by fire and holding a sword) or Fudo's Cape. The reason of the change of names was this.  Tarada Sees the Mysterious Figure of a Girl The

inhabitants of Amakusa lived almost entirely on what they got out of

the sea,

so that when it came to pass that for two years of the Bunroku period

no fish

came into their seas or bay and they were sorely distressed, many

actually

starved, and their country was in a state of desolation. Their largest

and

longest nets were shot and hauled in vain. Not a single fish so large

as a

sardine could they catch. At last things got so bad that they could not

even

see fish schooling outside their bay. Peculiar rumbling sounds were

occasionally heard coming from under the sea off Cape Fudo; but of

these they

thought little, being Japanese and used to earthquakes. All

the people knew was that the fish had completely gone — where they

could not

tell, or why, until one day an old and much-respected fisherman said: 'I fear,

my friends, that the noise we so often hear off Cape Fudo has nothing

to do

with earthquakes, but that the God of the Sea has been displeased.' One

evening a few days after this a sailing junk, the Tsukushi-maru,

owned

by one Tarada, who commanded her, anchored for the night to the lee of

Fudozaki. After

having stowed their sails and made everything snug, the crew pulled

their beds

up from below (for the weather was hot) and rolled them out on deck.

Towards

-the middle of the night the captain was awakened by a peculiar

rumbling sound

seeming to come from the bottom of the sea. Apparently it came from the

direction in which their anchor lay; the rope which held it trembled

visibly.

Tarada said the sound reminded him of the roaring of the falling tide

in the

Naruto Channel between Awa and Awaji Island. Suddenly he saw towards

the bows

of the junk a beautiful maid clothed in the finest of white silks (he

thought).

She seemed, however, hardly real, being surrounded by a glittering

haze. Tarada

was not a coward; nevertheless, he aroused his men, for he did not

quite like

this. As soon as he had shaken the men to their senses, he moved

towards the

figure, which, when but ten or twelve feet away, addressed him in the

most

melodious of voices, thus: 'Ah!

could I but be back in the world! That is my only wish.' Tarada,

astonished and affrighted, fell on his knees, and was about to pray,

when a

sound of roaring waters was heard again, and the white-clad maiden

disappeared

into the sea. Next

morning Tarada went on shore to ask the people of Amakusa if they had

ever

heard of such a thing before, and to tell them of his experiences. 'No,'

said the village elder. 'Two years ago we never heard the noises which

we hear

now off Fudo Cape almost daily, and we had much fish here before then;

but we

have even now never seen the figure of the girl whom (you say) you saw

last

night. Surely this must be the ghost of some poor girl that has been

drowned,

and the noise we hear must be made by the God of the Sea, who is in

anger that

her bones and body are not taken out of this bay, where the fish so

much liked

to come before her body fouled the bottom.' A

consultation was held by the fishermen. They concluded that the village

elder

was right — that some one must have been drowned in the bay, and that

the body

was polluting the bottom. It was her ghost that had appeared on

Tarada's ship,

and the noise was naturally caused by the angry God of the Sea,

offended that

his fish were prevented from entering the bay by its uncleanness. What

was to be done was quite clear. Some one must dive to the bottom in

spite of

the depth of water, and bring the body or bones to the surface. It was

a

dangerous job, and not a pleasant one either, — the bringing up of a

corpse

that had lain at the bottom for well over a year. As no

one volunteered for the dive, the villagers suggested a man who was a

great

swimmer — a man who had all his life been dumb and consequently was a

person of

no value, as no one would marry him and no one cared for him. His name

was

Sankichi or (as they called him) Oshi-no-Sankichi, Dumb Sankichi. He

was

twenty-six years of age; he had always been honest; he was very

religious,

attending at the temples and shrines constantly; but he kept to

himself, as his

infirmity did not appeal to the community. As soon as this poor fellow

heard

that in the opinion of most of them there was a dead body at the bottom

of the

bay which had to be brought to the surface, he came forward and made

signs that

he would do the work or die in the attempt. What was his poor life

worth in

comparison with the hundreds of fishermen who lived about the bay,

their lives

depending upon the presence of fish? The fishermen consulted among

themselves,

and agreed that they would let Oshi-no-Sankichi make the attempt on the

morrow;

and until that time he was the popular hero. Next

day, when the tide was low, all the villagers assembled on the beach to

give

Dumb Sankichi a parting cheer. He was rowed out to Tarada's junk, and,

after

bidding farewell to his few relations, dived into the sea off her bows.

Sankichi

swam until he reached the bottom, passing through hot and cold currents

the

whole way. Hastily he looked, and swam about; but no corpse or bones

did he

come across. At last he came to a projecting rock, and on the top of

that he

espied something like a sword wrapped in old brocade. On grasping it he

felt

that it really was a sword. On his untying the string and drawing the

blade, it

proved to be one of dazzling brightness, with not a speck of rust. 'It

is said,' thought Sankichi, 'that Japan is the country of the sword, in

which

its spirit dwells. It must be the Goddess of the Sword that makes the

roaring

sound which frightens away the fishes — when she comes to the surface.'

Feeling

that he had secured a rare treasure, Sankichi lost no time in returning

to the

surface. He was promptly hauled on board the Tsukushi-maru amid

the

cheers of the villagers and his relations. So long had he been under

water, and

so benumbed was his body, he promptly fainted. Fires were lit, and his

body was

rubbed until he came to, and gave by signs an account of his dive. The

head

official of the neighbourhood, Naruse Tsushimanokami, examined the

sword; but,

in spite of its beauty and excellence, no name could be found on the

blade, and

the official expressed it as his opinion that the sword was a holy

treasure. He

recommended the erection of a shrine dedicated to Fudo, wherein the

sword should

be kept in order to guard the village against further trouble. Money

was

collected. The shrine was built. Oshi-no-Sankichi was made the

caretaker, and

lived a long and happy life. The

fish returned to the bay, for the spirit of the sword was no longer

dissatisfied by being at the bottom of the sea. 1 The title

to this old and hitherto untold legend is not

much less curious than the story itself, which was told to me by a man

called

Fukuga, who journeys much up and down the southern coast in search of

pearls

and coral. |