| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| A STORY OF OKI ISLANDS THE

Oki Islands, some forty-five miles from the mainland of Hoki Province,

were for

centuries the scene of strife, of sorrow, and of banishment; but to-day

they

are fairly prosperous and highly peaceful. Fish, octopus, and

cuttlefish form

the main exports. They are a weird, wild, and rocky group, difficult of

access,

and few indeed are the Europeans who have visited them. I know of only

two — the

late Lafcadio Hearn and Mr. Anderson (who was there to collect animals

for the

Duke of Bedford). I myself sent Oto, my Japanese hunter, who was glad

to

return. In

the Middle Ages — that is, from about the year 1000 A.D. — there was

much

fighting over the islands by various chieftains, and many persons were

sent

thither in banishment. In

the year 1239 Hojo Yoshitoshi defeated the Emperor Go Toba and banished

him to

Dogen Island. Another

Hojo chieftain banished another Emperor, Go Daigo, to Nishi-no-shima.

Oribe

Shima, the hero of our story, was probably banished by this same Hojo

chieftain, whose name is given to me as Takatoki (Hojo), and the date

of the

story must be about 1320 A.D. At

the time when Hojo Takatoki reigned over the country with absolute

power, there

was a samurai whose name was Oribe Shima. By some misfortune Oribe (as

we shall

call him) had offended Hojo Takatoki, and had consequently found

himself

banished to one of the islands of the Oki group which was then known as

Kamishima (Holy Island). So the relater of the story tells me; but I

doubt his

geographical statement, and think the island must have been

Nishi-no-shima

(Island of the West, or West Island1). Oribe

had a beautiful daughter, aged eighteen, of whom he was as fond as she

was of

him, and consequently the banishment and separation rendered both of

them

doubly miserable. Her name was Tokoyo, O Tokoyo San. Tokoyo,

left at her old home in Shima Province, Ise, wept from morn till eve,

and

sometimes from eve till morn. At last, unable to stand the separation

any

longer, she resolved to risk all and try to reach her father or die in

the

attempt; for she was brave, as are most girls of Shima Province, where

the

women have much to do with the sea. As a child she had loved to dive

with the

women whose daily duty is to collect awabi and pearl-oyster shells,

running

with them the risk of life in spite of her higher birth and frailer

body. She knew

no fear. Having

decided to join her father, O Tokoyo sold what property she could

dispose of,

and set out on her long journey to the far-off province of Hoki, which,

after

many weeks she reached, striking the sea at a place called Akasaki,

whence on

clear days the Islands of Oki can be dimly seen. Immediately she set to

and

tried to persuade the fishermen to take her to the Islands; but nearly

all her

money had gone, and, moreover, no one was allowed to land at the Oki

Islands in

those days — much less to visit those who had been banished thence. The

fishermen laughed at Tokoyo, and told her that she had better go home.

The

brave girl was not to be put off. She bought what stock of provisions

she could

afford, at night went down to the beach, and, selecting the lightest

boat she

could find, pushed it with difficulty into the water, and sculled as

hard as

her tiny arms would allow her. Fortune sent a strong breeze, and the

current

also was in her favour. Next evening, more dead than alive, she found

her efforts

crowned with success. Her boat touched the shore of a rocky bay. O

Tokoyo sought a sheltered spot, and lay down to sleep for the night. In

the

morning she awoke much refreshed, ate the remainder of her provisions,

and

started to make inquiries as to her father's whereabouts. The first

person she

met was a fisherman. 'No,' he said: 'I have never heard of your father,

and if

you take my advice you will not ask for him if he has been banished,

for it may

lead you to trouble and him to death!' Poor

O Tokoyo wandered from one place to another, subsisting on charity, but

never

hearing a word of her father. One

evening she came to a little cape of rocks, whereon stood a shrine.

After

bowing before Buddha and imploring his help to find her dear father, O

Tokoyo

lay down, intending to pass the night there, for it was a peaceful and

holy

spot, well sheltered from the winds, which, even in summer, as it was

now (the

13th of June), blow with some violence all around the Oki Islands. Tokoyo

had slept about an hour when she heard, in spite of the dashing of

waves

against the rocks, a curious sound, the clapping of hands and the

bitter

sobbing of a girl. As she looked up in the bright moonlight she saw a

beautiful

person of fifteen years, sobbing bitterly. Beside her stood a man who

seemed to

be the shrine-keeper or priest. He was clapping his hands and mumbling

'Namu

Amida Butsu's.' Both were dressed in white. When the prayer was over,

the

priest led the girl to the edge of the rocks, and was about to push her

over

into the sea, when O Tokoyo came to the rescue, rushing at and seizing

the

girl's arm just in time to save her. The old priest looked surprised at

the

intervention, but was in no way angered or put about, and explained as

follows:

— 'It appears from your intervention that you are a stranger to this small island. Otherwise you would know that the unpleasant business upon which you find me is not at all to my liking or to the liking of any of us. Unfortunately, we are cursed with an evil god in this island, whom we call Yofuné-Nushi. He lives at the bottom of the sea, and demands, once a year, a girl just under fifteen years of age. This sacrificial offering has to be made on June 13, Day of the Dog, between eight and nine o'clock in the evening. If our villagers neglect this, Yofuné-Nushi becomes angered, and causes great storms, which drown many of our fishermen. By sacrificing one young girl annually much is saved. For the last seven years it has been my sad duty to superintend the ceremony, and it is that which you have now interrupted.'  0 Tokoyo sees the girl about to be thrown over cliff O

Tokoyo listened to the end of the priest's explanation, and then said: 'Holy

monk, if these things be as you say, it seems that there is sorrow

everywhere.

Let this young girl go, and say that she may stop her weeping, for I am

more

sorrowful than she, and will willingly take her place and offer myself

to

Yofuné-Nushi. I am the sorrowing daughter of Oribe Shima, a samurai of

high

rank, who has been exiled to this island. It is in search of my dear

father

that I have come here; but he is so closely guarded that I cannot get

to him,

or even find out exactly where he has been hidden. My heart is broken,

and I

have nothing more for which to wish to live, and am therefore glad to

save this

girl. Please take this letter, which is addressed to my father. That

you should

try and deliver it to him is all I ask.' Saying

which, Tokoyo took the white robe off the younger girl and put it on

herself.

She then knelt before the figure of Buddha, and prayed for strength and

courage

to slay the evil god, Yofuné-Nushi. Then she drew a small and beautiful

dagger,

which had belonged to one of her ancestors, and, placing it between her

pearly

teeth, she dived into the roaring sea and disappeared, the priest and

the other

girl looking after her with wonder and admiration, and the girl with

thankfulness. As we

said at the beginning of the story, Tokoyo had been brought up much

among the

divers of her own country in Shima; she was a perfect swimmer, and

knew,

moreover, something of fencing and jujitsu, as did many girls of her

position

in those days. Tokoyo

swam downwards through the clear water, which was illuminated by bright

moonlight. Down, down she swam, passing silvery fish, until she reached

the

bottom, and there she found herself opposite a submarine cave

resplendent with

the phosphorescent lights issuing from awabi shells and the pearls that

glittered through their openings. As Tokoyo looked she seemed to . see

a man

seated in the cave. Fearing nothing, willing to fight and die, she

approached,

holding her dagger ready to strike. Tokoyo took him for Yofuné-Nushi,

the evil

god of whom the priest had spoken. The god made no sign of life,

however, and

Tokoyo saw that it was no god, but only a wooden statue of Hojo

Takatoki, the

man who had exiled her father. At first she was angry and inclined to

wreak her

vengeance on the statue; but, after all, what would be the use of that?

Better

do good than evil. She would rescue the thing. Perhaps it had been made

by some

person who, like her father, had suffered at the hands of Hojo

Takatoki. Was

rescue possible? Indeed it was more: it was probable. So perceiving,

Tokoyo

undid one of her girdles and wound it about the statue, which she took

out of

the cave. True, it was waterlogged and heavy; but things are lighter in

the

water than they are out, and Tokoyo feared no trouble in bringing it to

the

surface — she was about to tie it on her back. However, the unexpected

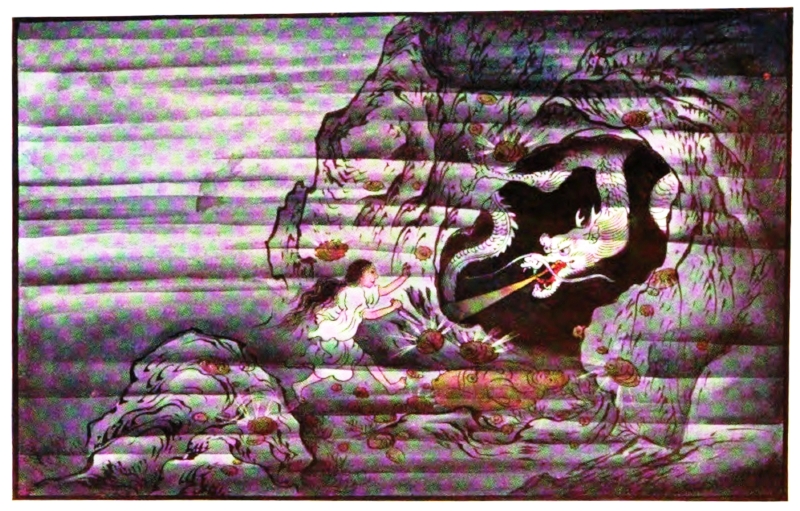

happened.  O Tokoyo sees Yofuné-Nushi Coming Towards Her She

beheld, coming slowly out of the depths of the cavern, a horrible

thing, a

luminous phosphorescent creature of the shape of a snake, but with legs

and

small scales on its back and sides. The thing was twenty-seven or eight

shaku

(about twenty-six feet) in length. The eyes were fiery. Tokoyo

gripped her dagger with renewed determination, feeling sure that this

was the

evil god, the Yofuné-Nushi that required annually a girl to be cast to

him. No

doubt the Yofuné-Nushi took her for the girl that was his due. Well,

she would

show him who she was, and kill him if she could, and so save the

necessity of

further annual contributions of a virgin from this poor island's few. Slowly

the monster came on, and Tokoyo braced herself for the combat. When the

creature was within six feet of her, she moved sideways and struck out

his

right eye. This so disconcerted the evil god that he turned and tried

to

re-enter the cavern; but Tokoyo was too clever for him. Blinded by the

loss of

his right eye, as also by the blood which flooded into his left, the

monster

was slow in his movements, and thus the brave and agile Tokoyo was able

to do

with him much as she liked. She got to the left side of him, where she

was able

to stab him in the heart, and, knowing that he could not long survive

the blow,

she headed him off so as to prevent his gaining too far an entrance

into the

cave, where in the darkness she might find herself at a disadvantage.

Yofuné-Nushi, however, was unable to see his way back to the depths of

his

cavern, and after two or three heavy gasps died, not far from the

entrance. Tokoyo

was pleased at her success. She felt that she had slain the god that

cost the

life of a girl a-year to the people of the island to which she had come

in

search of her father. She perceived that she must take it and the

wooden statue

to the surface, which, after several attempts, she managed to do, —

having been

in the sea for nearly half-an-hour. In

the meantime the priest and the little girl had continued to gaze into

the

water where Tokoyo had disappeared, marvelling at her bravery, the

priest

praying for her soul, and the girl thanking the gods. Imagine their

surprise

when suddenly they noticed a struggling body rise to the surface in a

somewhat

awkward manner! They could not make it out at all, until at last the

little

girl cried, 'Why, holy father, it is the girl who took my place and

dived into

the sea! I recognise my white clothes. But she seems to have a man and

a huge

fish with her.' The

priest had by this time realised that it was Tokoyo who had come to the

surface, and he rendered all the help he could. He dashed down the

rocks, and

pulled her half-insensible form ashore. He cast his girdle round the

monster,

and put the carved image of Hojo Takatoki on a rock beyond reach of the

waves. Soon

assistance came, and all were carefully removed to a safe place in the

village.

Tokoyo was the heroine of the hour. The priest reported the whole thing

to

Tameyoshi, the lord who ruled the island at the time, and he in his

turn

reported the matter to the Lord Hojo Takatoki, who ruled the whole

Province of

Hoki, which included the Islands of Oki. Takatoki

was suffering from some peculiar disease quite unknown to the medical

experts

of the day. The recovery of the wooden statue representing himself made

it

clear that he was labouring under the curse of some one to whom he had

behaved

unjustly — some one who had carved his figure, cursed it, and sunk it

in the

sea. Now that it had been brought to the surface, he felt that the

curse was

over, that he would get better; and he did. On hearing that the heroine

of the

story was the 'daughter of his old enemy Oribe Shima, who was confined

in

prison, he ordered his immediate release, and great were the rejoicings

thereat. The

curse on the image of Hojo Takatoki had brought with it the evil god,

Yofuné-Nushi, who demanded a virgin a-year as contribution.

Yofuné-Nushi had

now been slain, and the islanders feared no further trouble from

storms. Oribe

Shima and his brave daughter O Tokoyo returned to their own country in

Shima

Province, where the people hailed them with delight; and their

popularity soon

re-established their impoverished estates, on which men were willing to

work

for nothing. In

the island of Kamijima (Holy Island) in the Oki Archipelago peace

reigned. No

more virgins were offered on June 13 to the evil god, Yofuné-Nushi,

whose body

was buried on the Cape at the shrine where our story begins. Another

small

shrine was built to commemorate the event. It was called the Tomb of

the Sea

Serpent. The

wooden statue of Hojo Takatoki, after much travelling, found a

resting-place at

Honsoji, in Kamakura. __________________________________

1 Since writing this, I have found that there is a very small island, called Kamishima, between the two main islands of the Oki Archipelago, south-west of the eastern island. |