copyright, Kellscraft

Studio

1999-2002

(Return to Web Text-ures)

My Garden

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

(HOME)

|

|

Click Here to return to My Garden Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

|

JULY

PROBLEMS What right have we to blame the Garden Because the plant has withered there?’ — Hafiz. JULY

is often a discouraging

month to a gardener who does not employ a great many annuals. Following

upon the

exuberance of June, it seems a sort of pause, a breathing spell before

the grand

display of almost unfailing Phioxes and their train of late summer

flowers. It

is quite true that there are not as many well-known flowers belonging

to this

month and, in consequence, many gardens are quite scantily clothed with

bloom.

For years my own June pride was regularly shattered by the blank which

followed

the departure of the Flag Irises, Paeonies, and tumultuous Roses, and

it

required many years of study and “trying out” before I learned how many

fine

plants there are, other than annuals, with which to beautify this high

noon of

the year. In July,

also, we

have the elements against us; whether it is against

pitiless drought or fierce electric storms that we must contend, it is

very

difficult to keep the garden in good condition and the plants are bound

to

suffer somewhat. In time of drought the garden assumes an air of

passive

endurance; one does not feel the

growing and blowing, and while there may be plenty of bloom, it appears

to be

produced without enthusiasm and quite lacks the spontaneous exuberant

quality

that one is conscious of in the earlier year. Then must we stir the

soil

assiduously to conserve what little moisture there may be left and

water

whenever that may be done thoroughly, as surface wettings do more harm

than

good. Hardly less

painful

to the plants are the electric storms with twisting,

devastating winds and pounding rains, and woe to the gardener who has

not done

his staking in season and with intelligence! A prostrate garden is his

bitter

portion, and not all the king’s horses and all the gardeners in the

world can

repair the broken stalks of Larkspur and Hollyhock, raise up the

crushed masses

of Coreopsis, Gypsophila, and Anthemis, or mend the snapped stems of

lovely

Lilies. A storm, such as we are all familiar with, can do damage in

half an hour

that we, even with Nature’s willing cooperation, may not repair in many

weeks.

But with faithful cultivation, intelligent watering and staking, and a

knowledge

of the plants at one’s command, much may be done to avert calamity and

to make

this month a month as full of interest and beauty as the gay seasons

past and to

come. Tall spires

of

Larkspur are still reaching skyward when July comes in.

Sweet Williams, Coreopsis, Scarlet Lychnis, Madonna and Herring Lilies

are still

in good order, and there is often a host of self-sown or early sown

annuals

creating bright patches of colour about the borders, but in our garden

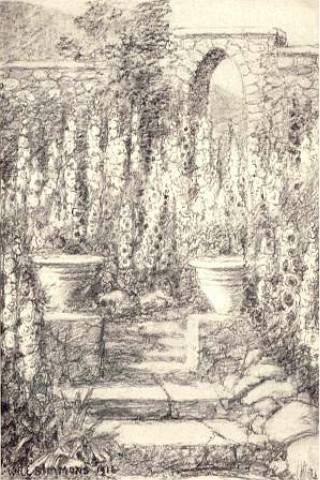

the most

prominent features of early July are Hollyhocks and the great sunshiny

Mulleins. For many

years a

hideous disfiguring disease rendered Hollyhocks almost

useless for garden purposes and it was only in out-of-the-way corners

in humble

gardens that this poor plant, once so lauded and admired, raised its

stricken

head. The disease first shows itself in ugly brown pimples on the under

side of

their foliage and it works so quickly that soon the whole flower stalk

stands

bravely flying its colours still, but denuded of its greenery or with a

few

tattered leaves hanging forlornly about it. Much has been done of late

years,

however, by lovers of the Hollyhock to alleviate its sufferings, and it

is now

quite possible with a few precautions or remedies to have this splendid

flower

in its integrity. We seldom have a diseased plant in our garden, and

our secret

is simply to give them plenty of sun and air, a rich soil, and to treat

them as

biennials. Old plants are much more apt to have the disease, and

Hollyhocks are

so easily raised from seed that to keep up a stock of young ones in the

nursery

is a very simple matter. We dig up the old plants and throw them away.

Plants

out in the open (not against walls or fences) where the air may

circulate freely

about them are much more likely to be healthy, but we have found that

by using

only young plants we can put them in almost any position. Bone meal and

wood

ashes are both good as tonics for the Hollyhocks, and there are a

number of

sprays recommended for afflicted plants. Bordeaux mixture used several

times in

spring is an old reliable remedy, and Mr. C. H. Jenkins in his “Hardy

Flower

Book” recommends a treatment the simplicity of which is certainly in

its

favour: “Use a breakfast cup full of common salt to three gallons of

water.

Employ an Abol syringe with fine mist-like spray so that the solution

does not

reach the roots of the plant.” This should be done about every two

weeks in

spring.  "Hollyhocks are among the most pictorial of plants, and it is very difficult to find anything else to take their place. I like best the single ones in pink and blackish crimson, pale yellow and pure white, but the double ones are very fine and opulent, and the lovely shades and tints to be had very numerous." Hollyhocks

are among

the most pictorial of plants, and it

is very difficult to find anything else to take their place. I like

best the

single ones in pink and blackish crimson, pale yellow and pure white,

but the

double ones are very fine and opulent, and the lovely shades and tints

to be had

very numerous. One I had from Eng land, called Prince of Orange, was a

splendid

orange-copper colour, and there are now many named varieties. I have a

fine

group of salmon-pink Hollyhocks against a large tree of the

Purple-leaved Plum,

and another cherry-coloured group has a fine background a pink Dorothy

Perkins

Rose which drapes the wall behind it. White Hollyhocks are fine with

Tiger

Lilies, and there are many other good associations for them. Althaea

ficifolia

is a very pretty pale yellow-flowered single sort called the Fig Leaved

Hollyhock. This plant is slender in growth and sends up lateral stalks

which

keep it in bloom all summer long. Next to

Hollyhocks,

or quite equal to them in picturesque value, save that

they have not the wide colour range, are the radiant Mulleins. Every

one knows

the noble outline of the wild Mullein, Verbascum

Thapsus, and also its bad habit of opening but a few of

its blossoms at a time. The foreign and hybrid Mulleins have the same

splendid

form and clothe their great candelabra-like stalks in solid bloom which

continues to develop during the greater part of the summer. Mulleins

are friends

of only about four years’ standing, but to no other flower am I more

grateful

for fine and lasting effect. Their soft yellow colour is so sunshiny as

to

really seem to cast a radiance and is so non-combative as to affiliate

well with

almost any other colour. The splendid V.

Olympicum was the first I knew. It is, like most of the

others,

biennial in character and grows seven feet high. V.

phlomoides is as splendid and as tall, and V. pannosum has woolly leaves and grows

about five feet high. V.

phoeniceum

is a low-growing

sort,

two feet, sending up from a flat rosette

of leaves a spike set with flowers of rose or purple or white, but this

sort

seems to me much less worthy than the others. V.

nigrum has yellow flowers marked with purple and grows four

feet tall; there

is a white variety of this. Of late

years a

number of good hybrids have been created among which

Harkness Hybrid, four feet tall with yellow flowers, is one of the

best. Miss

Willmot is a beautiful long-lasting variety bearing large white flowers

on stems

six feet high, and Caledonia is a lower growing sort with

sulphur-yellow flowers

suffused with bronze and purple. There are two verbascums, namely densiflorum

and newryensis, which

are said to be true perennials, but I have not yet

procured them. The

Mulleins are

splendid plants for our American gardens for they love a

warm, dry soil and this we can certainly give them. They are easily

raised from

seed, perfectly hardy, and as they self-sow freely it is not necessary

to keep

up a stock in the nursery. The Greek Mullein, V.

olympicum, which is my favourite, takes three years to

develop

its blooming ability with me, so I keep the great rosettes in the

nursery for

the first two. The tall-growing Mulleins are splendid plants for the

back of the

border and are lovely as a background for blue and silver Sea Hollies

and Globe

Thistles. The

handsome Yarrow

family offers several strong-growing and

drought-resisting subjects for the July garden. They present no

difficulty in

the way of cultivation and will grow in poor, dry soil if they must,

but require

yearly division. Achillea filipendulina (syn.

Eupatorium), in a variety

known as

Parker’s, is the flower of the flock. It grows in strong clumps

throwing up

stems four feet high nicely clothed with feathery foliage and

terminating in

broad corymbs of golden bloom. This plant is ornamental from the first

appearance of its pleasant green in spring until autumn when the yellow

flower

heads have softened to a warm brown. It lives out its span of life in

dignity

and order, for its foliage remains in good condition to the last and it

has no

fuzzy untidy way of perpetuating itself. A cool

picture for

this summer season may be created with tall white

Hollyhocks, Parker’s Yarrow, early white Phlox, Miss Lingard, and a

foreground

of Anthemis Kelwayi. A patch of tawny Hemerocallis

fulva is a good neighbour for this group. Blue and white

Aconites are fine

with this Yarrow and also that splendid hardy plant, Erigeron

speciosus var. superbus,

which grows about two and one-half feet high and bears

innumerable

daisy-like

flowers of a fine lilac-purple from June until September. It may be

easily

raised from seed and will sometimes bloom the same season as sown. Achillea

sericea is

a good Yarrow having much the character of Parker’s save that it grows

but

eighteen inches high and starts to flower in June. A.

ptarmica,

fl. pl., otherwise known as The Pearl, we

have banished from our

borders though it is a much-lauded plant by many and is good for

cutting; it has

no domestic qualities, must rove and stray, insinuating its wandering

rootlets

into the internal affairs of its neighbours and choking out many a

timid

resident. Its bloom is pretty and fluffy but its stems are weak and

vacillating;

altogether a frivolous and unstable creature to my thinking. There are

some good

little alpine Yarrows with gray foliage quite charming for creeping

among the

stones at the edge of the border. A.

umbellata has pure-white flower beads. A.

tomentosa has dark prostrate foliage and yellow flowers; argentea

has silvery foliage and white flowers. This little

plant

grows four inches

high and the other two about six. There is no

more

important plant in the mid-summer garden than Gypsophila

paniculata, variously known as Chalk Plant, or Baby’s

Breath, and called

by the children here “Lace Shawls.” Seemingly oblivious to scorching

sun and

prolonged drought, it coolly carries out its delicate plan of existence

from

silver haze to cool white mist to fragile brown oblivion. No plant is

so

exquisite an accompaniment to so many others; indeed, any spot where it

grows

will soon become a lovely picture without our agency. Poppies sow their

seed

about it and rest their great blossoms upon its cloudlike bloom, and

Nigellas

and Snapdragons are particularly fine in association with it. One very

pretty

group here has Stachys lanata as a

foreground with its gray velvet foliage and stalks of bloom now

colouring to a

pinky mauve. Behind is the cloudlike mound of Gypsophila, and resting

upon it,

its large flowers partly obscured by the mist, is a pinkish-mauve Clematis kermesina. The vine is supported upon

pea-brush which does

not show behind the Gypsophila. In another

corner

that lovely and courageously magenta sprawler, Callirhoe

involucrata, glistens exquisitely through the mist, and white Lilies

rise in

silver harmony behind. The double-flowered Gypsophila is a less

ethereal but

very beautiful plant and should find a borne in every garden. The

single sort is

easily raised from seed but does not make any great show until the

third year. G.

repens is a fine little trailer for the edge of the border

with a long

period of bloom. The

Moonpenny

Daisies, Chrysanthemum

maximum, are invaluable among mid-summer flowers. They make

stout bushy

clumps of dark foliage, two to three feet tall, with large, glistening,

marguerite-like flowers of much substance. They spread broadly and

should be

divided every year, and they enjoy a moderately rich soil and sunshine.

Good

varieties are Mrs. C. Lowthian Bell, King Edward VII, Robinsoni, Mrs.

F.

Daniels, Mrs. Terstag, Alaska, and Kenneth. They are easily raised from

seed and

last a long time in bloom. The china whiteness of these blooms is a

little hard

so that they are at their best when associated with the softening

influence of

such plants as the Artemisias, Rue, Stachys, Gypsophila, and Lyme Grass. Goat’s Rue (Galega officinalis) is

a soft-coloured delightful plant of the present season with attractive

foliage

and a good habit of growth. It is fine with Campanula

lactoflora var. magnifica

and

late Orange Lilies. The delicate lavender sort is the prettiest, I

think, though

the white is also desirable; var. Hartlandi

is considered an improvement. Several

fine

blue-flowered families make valuable contributions to the

July garden and linger into August —

Veronicas,

Aconites, Platycodons, Eryngiums, and Echinops. The

Veronicas are a

splendid race with good foliage and attractive spikes

of bloom, blue, rose, or white. Most of them are plants for the middle

of the

border, though the silver-leaved V. incana

belongs in the front row with repens

and

prostrata, and the tall virginica

may have a place at the back. V.

spicata grows almost eighteen inches tall and bears many

spikes of

bright-blue flowers and has a good white variety and a washed-out rose

sort. If

cut after blooming it will bloom again toward autumn. V.

virginica grows

from four to six feet high and appreciates a heavy soil. Its feathery

flower

spikes (white) are very pretty as a background for salmon Phloxes such

as

Elizabeth Campbell or Mrs. Oliver. It is also well placed with the Rose

Loosestrife. The head of the family is Veronica

longifolia var. subsessilis

whose

sonorous name in no way belies the vigorous dignity and importance of

the plant.

Its foliage is rich and strong, and in late July and August its long

sapphire

spikes of bloom are a delight indeed. If the season is not too dry it

remains a

long time in perfection and is on hand to welcome and complete the

beauty of

some of the softly coloured pink Phioxes, Peach Blow, in particular,

with the

becoming addition to the group of some metallic Sea Hollies. I must

confess to

having had some trouble with this Veronica; it certainly

suffers from the drought, turning rusty in its nether parts, and yet

seems to

want a full view of the sun for, planted in shade, it languishes

immediately. A

rich retentive soil seems to bring it to fullest perfection, and it

more than

repays any trouble bestowed upon it. A little bone meal dug in about

its roots

in May strengthens its growth and seems to improve the colour of its

flower

spikes. I have not been able to raise this plant from seed, but it is

easily

increased by division of the roots in spring or by soft cuttings. I

should

advise planting it in spring as it is important that it should be well

established before winter. The

Platycodons are

closely connected with the house of Campanula. There

are only three kinds in cultivation and they are easily raised from

seed. P.

grandiflorum grows about two feet high and bears

many widely spreading

steel-blue bells. The lovely white var. album

is faintly lined with blue and always makes me think of

the

fresh blue and

white aprons of little girls. The flowers of P.

Mariesi are a somewhat less clouded blue and the plant is

dwarf and compact. Chinese

Belifiowers

have a disadvantage in the brittleness of their stems.

After a heavy rain they will be found flat upon the ground never to

rise again,

and they are difficult to support inconspicuously by the ordinary

method of

stake and raffia. I grow mine in good-sized clumps and stick stout,

widely

spread pieces of pea-brush about among them. This is the most

satisfactory

method, for it allows some of the stems to fall forward a little,

giving to the

clump an agreeable rounded outline. The thick fleshy root of the

Platycodon

seems to enable it to ignore the drought, and its clean-cut,

fresh-coloured

blossoms are always a pleasant sight in the garden. The

beautiful family

of Aconites I always hesitate to

recommend as the whole plant is very poisonous when eaten and, where

there are

children, might prove a serious danger. My own children know it well

and its

deadly consequences and avoid it assiduously. The fact that they are

tall plants

suitable for the back of the border makes it possible to put them

pretty well

out of reach, and they are among the most beautiful of the flowers

blooming in

mid-summer and autumn. They have long been among garden flowers; the

old

gardeners, Parkinson and Gerarde, give long lists of sorts,

interspersing their

admiring descriptions with illustrated warnings of the dire results of

eating

any part of the plant. Gerarde writes of A.

Napellus: “this kinde

of

Wolfesbane, called Napellus vernus, in English,

Helmet-flowers, or the Great Monkshood beareth very faire and goodly

blew

flowres in shape like an helmet, which are so beautiful that a man

would thinke

they were of some excellent vertue — but, non est semper fides habenda

fronti.”

The foliage is beautiful and shining, “much spread abroad and cut into

many

flits and notches.” The flowering of Aconites covers a long period. The

earliest here is a clouded blue sort with shining foliage which came to

me as A.

tauricum. It blooms in late June and July and is not more

than three feet

high. This was the first Aconite I grew, and, after reading the early

herbalists, my mind was rather filled with the evil reputation of the

plant so,

when an army of little wicked-looking black toadstools appeared over

night about

the beautiful plant, it seemed most fitting

— like

an evil spirit and his minions. The Napellus varieties,

the dark blue, pure white, and most of all, the bicolour, are all

lovely and

graceful plants growing about five feet tall and blooming through

mid-summer. A.

Wilsoni and Spark’s variety are

magnificent plants growing five or six feet

high and bearing their spikes of rich-coloured hooded flowers in August

and

September. A. Fischeri is a clear

blue

sort not more than two feet high, which bridges the time between Wilsoni

and the October blooming A.

autumnale.

There are two yellow-flowered sorts, lycoctonum

and pyrenaicum, two

and

four feet

high respectively, which bloom in August and September. The

Aconites are

impatient of a dry soil, so it should be rich and

retentive. A north border suits them very well as they enjoy some

shade, and

they should be taken up and divided about every three years. I am very

fond of a

group of A. Napellus var. bicolour

and Tiger Lilies which fills the angle made by the high

wall

and the garden

house. The clean blue and white of these Aconites accompanies well the

strange

tawny hue worn by the Tiger Lilies and, lower down, a fine group of

pure orange

Bateman’s Lily, growing behind the spreading light-green foliage of Funkia

subcordata, completes a good north border group. They are

also fine with the

Phloxes — pink and white and scarlet. One would

not

willingly do without the beautiful Monkshoods, so valuable

are they in the summer and autumn gardens; but, in all our dealings

with this

“venomous and naughty herb,” it is well to remember the terse warning

of

Dodoens that it is “very hurtful to man’s nature and killeth out of

hand.” Eryngiums,

or Sea

Hollies, are plants of great interest and beauty, their

silvery stems and foliage and deep-blue globular flower heads creating

an

unusually lovely effect. They are easily raised from seed and seem to

take

kindly to any soil in a sunny situation. E.

maritimum, the true Sea Holly, is a low-growing plant for

the front of the

border with large glaucous foliage. B. alpinum

and Oliverianum, two

and

one-half

and three feet in height, with rich blue flower heads, are the best, I

think,

though planum, bearing an immense

quantity of small blue flowers and amethystinum,

more gray than blue, are both extremely good. Their

subdued

and charming

colour scheme enables us to use them with many flowers of their day.

Most

interesting are they with the Aconites and blue Veronicas, with Tiger

Lilies or

flame-coloured Phlox. With all the pink Phioxes they are lovely, but

with the

delicate Mme. Paul Dutre they produce a particularly charming harmony. Somewhat

resembling

the Sea Hollies are the Globe Thistles (Echinops) of

which E. Ritro, three feet, and bannaticus,

five feet, are good representatives. Both have metallic

blue,

thistle-like

flowers and glaucous foliage. These may be used in the same colour

combinations

as the Sea Hollies and are as useful. A beautiful and little used native plant of late July is the Rose Loosestrife, Lythrum Salicaria var. rosea superba. It is a tall plant, four feet in height, carrying its leafy branches erectly and bearing at the top of each a long spike of rose or, perhaps one should admit, magenta flowers. But no one need hold aloof from what they are pleased to call “that fighting colour,” for it is so frank and clean and splendid in this plant that it can but win admiration and respect. Pale, ivory-coloured Hollyhocks are charming in its neighbourhood, and such buff-coloured Gladioli as Isaac Buchanan. White Phlox and garnet Hollyhocks become it well, and a daring but successful association for it is strong blue Monkshood and blue-green Rue. It is not a plant which requires frequent division, but it desires a deep, retentive soil and a sunny situation. |