|

Click

here to return to

When Life Was Young At the Old Farm in Maine Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

CHAPTER XXX

A HEARTFELT THANKSGIVING AND A MERRY YOUNG MUSE THAT VISITED US UNINVITED Thanksgiving was always a holiday at the old farm.

Gram and the girls made extensive preparations for it and intended to have a fine

dinner. Besides the turkey and chickens there were "spareribs" and

great frying-panfuls of fresh pork which, at this cold season of the year, was

greatly relished by us. On this present Thanksgiving-day, two of Gram's nephews

and their wives were expected to visit us, as also several cousins of whom I

had heard but vaguely. It chanced, too, that on this occasion we had

especially good reason to be thankful that we were alive to eat a Thanksgiving

dinner of any kind, as I will attempt to relate. Up to the day before

Thanksgiving the weather, with the exception of two light snow storms, had been

bright and pleasant, and the snow had speedily gone off. On that day there came

a change. The Indian-summer mildness disappeared. The air was very still, but a

cold, dull-gray haze mounted into the sky and deepened and darkened. All warmth

went out from beneath it. There was a kind of stone-cold chill in the air which

made us shiver. "Boys, there's a 'snow bank' rising," the

Old Squire remarked at dinner. "The ground will close for the winter. Glad

we put those boughs round the house yesterday and banked up the

out-buildings." The sky continued to darken as the vast, dim pall of

leaden-gray cloud overspread it, and cold, raw gusts of wind began to sigh

ominously from the northeast. Gramp at length came out where we were wheeling

in the last of the stove-wood. "Have you seen the sheep to-day?" he

asked Addison. "There is a heavy snow storm coming on. The flock must be

driven to the barn." None of us had seen the sheep for several days; the

flock had been ranging about; and Halse ran over to the Edwardses to learn

whether they were there, but immediately returned, with Thomas who told us that

he had seen our sheep in the upper pasture, early that morning, and theirs with

them. Immediately then we four boys rigged up in our

thickest old coats and mittens, and set off — with salt dish — to get the sheep

home. The storm had already obscured the distant mountains to eastward when we

started; and never have I seen Mt. Washington and the whole Presidential Range

so blackly silhouetted against the westerly sky as on that afternoon, from the

uplands of the sheep pasture. The pasture was a large one, containing nearly a

hundred acres, and was partially covered by low copses of fir. Seeing nothing

of the sheep there, we followed the fences around, then looked in several

openings which, like bays, or fiords, extended up into the southerly border of

the "great woods." And all the while Tom, who was bred on a farm and

habituated to the local dialect concerning sheep, was calling, "Co'day,

co'day, co'nanny, co'nan." But no answering ba-a-a was heard. "They are not here," Addison exclaimed at

length. "The whole flock has gone off somewheres." "Most likely to 'Dunham's open,'" said Tom,

"and that's two miles; but I know the way. Come on. We've got to get

them." We set off at a run, following Thomas along a trail

through the forest across the upper valley of the Robbins Brook, but had not

gone more than a mile when the storm came on, not large snowflakes, but thick

and fine, driven by wind. It came with a sudden darkening of the woods and a

strange deep sound, not the roar of a shower, but like a vast elemental sigh

from all the surrounding hills and mountains. The wind rumbled in the high, bare

tree-tops and the icy pellets sifted down through the bare branches and rattled

inclemently on the great beds of dry leaves. "Shall we go back?" exclaimed Halse. "No, no; come on!" Thomas exclaimed.

"We've got to get those sheep in to-night." We ran on; but the forest grew dim and obscure.

"I think we have gone wrong," Addison said. "I 'most think we

have," Thomas admitted. "I ought to have taken that other path, away

back there." He turned and ran back, and we followed to where another

forest path branched easterly; and here, making a fresh start, we hastened on

again for fifteen or twenty minutes. "Oughtn't we to be pretty near Dunham's

open?" demanded Addison. "Oh, I guess we will come to it," replied

Tom. "It is quite a good bit to go." Thereupon we ran on again for some time, and crossed

two brooks. By this time the storm had grown so blindingly thick that we could

see but a few yards in any direction. Still we ran on; but not long after, we

came suddenly on the brink of a deep gorge which opened out to the left on a

wide, white, frozen pond. Below us a large brook was plunging down the

"apron" of a log dam. Thomas now pulled up short, in bewilderment. Addison

laughed. "Do you know where you are?" said he. "Tom, that is

Stoss Pond and Stoss Pond stream. There's the log dam and the old camp where

Adger's gang cut spruce last winter. I know it by those three tall pine stubs

over yonder." Tom looked utterly confused. "Then we are five

miles from home," he said, at length. "We had better go back, too, as quick as we

can!" Halse exclaimed, shivering. "It's growing dark! The ground is

covered with snow, now!" Addison glanced around in the stormy gloom and shook

his head. "Tom," said he, "I don't believe we can find our way

back. In fifteen minutes more we couldn't see anything in the woods. We had

better get inside that camp and build a fire in the old cook-stove." "I don't know but that we had," Tom

assented. "It's an awful night. Only hear the wind howl in the

woods!" We scrambled down the steep side of the gorge to the

log camp, found the old door ajar and pushed in out of the storm. There was a

strange smell inside, a kind of animal odor. By good fortune Addison had a few

matches in the pocket of the old coat which he had worn, when we went on the

camping-trip to the "old slave's farm." He struck one and we found

some dry stuff and kindled a fire in the rusted stove. There were several

logger's axes in the camp; and Tom cut up a dry log for fuel; we then sat

around the stove and warmed ourselves. "I expect that the folks will worry about

us," Thomas said soberly. "Well, it cannot be helped," replied

Addison. "But we haven't a morsel to eat here," said

Halse. "I'm awfully hungry, too." Thereupon Tom jumped up and began rummaging, looking

in two pork barrels, a flour barrel and several boxes. "Not a scrap of

meat and no flour," he exclaimed. "But here are a few quarts of white

beans in the bottom of this flour barrel; and we have got the sheep salt. What

say to boiling some beans? Here's an old kettle." "Let's do it!" cried Halse. A kettle of beans was put on and the fire kept up, as

we sat around, for two or three hours. Meantime the storm outside was getting

worse. Fine snow was sifting into the old camp at all the cracks and crevices.

The cold, too, was increasing; the roaring of the forest was at times

awe-inspiring. On peeping out at the door, nothing could be discerned; snow

like a dense white powder filled the air. Already a foot of snow had banked

against the door; the one little window was whitened. Occasionally, above the

roar in the tree-tops, could be heard a distant, muffled crash, and Tom would

exclaim, "There went a tree!" We got our beans boiled passably soft, after awhile,

and being very hungry were able to eat a part of them, well salted. Boiled beans

can be eaten, but they can never rank as a table luxury. While chewing our beans, toward the end of the

repast, an odd sound began to be heard, as of some animal digging at the door,

also snuffling, whimpering sounds. We listened for some moments. "Boys, you don't suppose that's Tyro, do

you?" cried Tom at length. "I'll bet it is! He has taken my track and

followed us away up here!" — and jumping up, Tom ran to the door.

"Tyro" was a small dog owned at the Edwards homestead. When, however, he opened the door a little, there

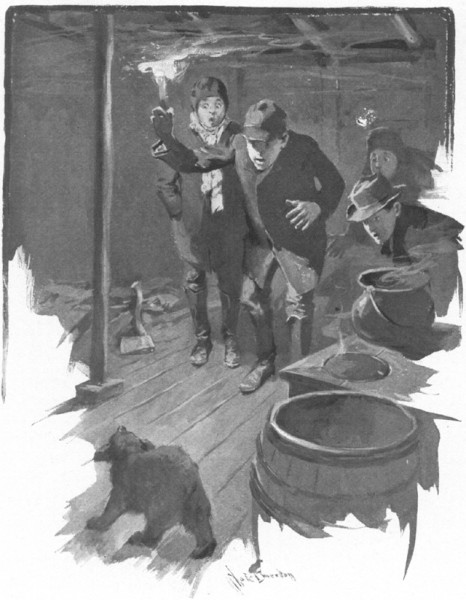

crept in, whimpering, not Tyro, but a small, dark-colored animal, which the

faint light given out from the stove scarcely enabled us to identify. The

creature ran behind the barrels; and Tom clapped the door to. Addison lighted a

splinter and we tried to see what it was; but it had run under the long bunk

where the loggers once slept. After a flurry, we drove it out in sight again,

when Tom shouted that it was a little "beezling" of a bear! "Yes, sir-ee, that's a little runt of a bear cub,"

he cried. "He's been in this old camp before. That's what made it smell so

when we came in." Addison imagined that this cub had run out when he

heard us coming to the camp, but that the severity of the storm had driven it

back to shelter. It was truly a poor little titman of a bear. At length we

caught it and shut it under a barrel, placing a stone on the top head.

THE BEEZLING BEAR. After our efforts cooking beans and the fracas with

the "beezling bear," it must have been eleven o'clock or past, before

we lay down in the bunk. The wind was still roaring fearfully, and the fine

snow sifting down through the roof on our faces. In fact, the gale increased

till past midnight. Addison said that he would sit by the stove and keep fire.

Tom, Halse and I lay as snug as we could in the bunk, with our feet to the

stove and presently fell asleep. But soon a loud crack waked us, so harsh, so

thrilling, that we started up. Addison had sprung to his feet with an

exclamation of alarm. One of those great pine tree-stubs up the bank-side,

above the camp, had broken short off in the gale. In falling, it swept down a

large fir tree with it. Next instant they both struck with so tremendous a

crash, one on each side of the camp, that the very earth trembled beneath the

shock! The stove funnel came rattling down. We had to replace it as best we

could. It was not till daylight, however, that we fully

realized how narrowly we had escaped death. A great tree trunk had fallen on

each side of the camp, so near as to brush the eaves of the low roof. Dry stubs

of branches were driven deep into the frozen earth. Either trunk would have

crushed the old camp like an eggshell! The pine stub was splintered and split

by its fall. There was barely the width of the camp between the two trunks, as

they lay there prone and grim, in the drifted snow. The gale slackened shortly after sunrise and the

storm cleared in part; although snow still spit spitefully till as late as ten

o'clock. "What a Thanksgiving-day!" grumbled Halse. After a time we started for home, leaving the little

bear shut up. As much as two feet of snow had fallen on a level and the drifts

in the hollows were much deeper. It was my first experience of the great snow

storms of Maine; my legs soon ached with wallowing, and my feet were

distressingly cold. Our homeward progress was slow; none the less, Tom

and Addison decided to go to Dunham's open, which was nearly a mile off our

direct course, to look for the sheep. Now that it was light, they knew the way.

Halse refused to go; and as my legs ached badly, he and I remained under a

large fir tree beside the path, the fan-shaped branches of which, like all the

other evergreens, were encrusted and loaded down by a white canopy. Addison and Thomas set off and were gone for more

than an hour, but had a large story to tell when they rejoined us. Not only had

they found the flock, snowbound, in Dunham's open, but had seen two deer which

had joined the sheep during the storm. The whole flock was in a copse of firs,

in the lee of the woods; and two loup-cerviers were sneaking about near by.

Thomas declared that their tracks were as large as his hand; and Addison said

that they had trodden a path in a semicircle around the flock. We resumed our wallowing way home, but erelong heard

a distant shout. Addison replied and immediately we saw two men a long way off

in the sheep pasture, advancing to meet us. "I expect that one of them is my good dad,"

Thomas remarked dryly. "If I know my mother, she has been worrying about

this cub of hers all night." It proved to be farmer Edwards, as Tom had surmised,

and with him the Old Squire, himself. "Well, well, well, boys, where have you been all

night?" was their first salutation to us. Addison gave a brief account of our adventure; we

then proceeded homeward together, and were in time for Gram's Thanksgiving

dinner at three o'clock, for which it is needless to say that we brought large

appetites. But I recall that the pleasures of the table for me were somewhat

marred by my feet which continued to ache and burn painfully for two or three

hours. There was a snowdrift six feet in depth before the

farmhouse piazza. The drifts indeed had so changed the appearance of things

around the house and yard that everything looked quite strange to me. None of the guests, whom we had expected to dinner,

came, on account of the storm; but a rumor of our adventure at the logging-camp

had spread through the neighborhood; and at night, after the road had been

"broken" with oxen, sled and harrow, Ned Wilbur and his sisters, the

Murch boys, and also Tom and Catherine, called to pass the evening. Perhaps the snow storm with its bewildering whiteness

had turned our heads a little. That, or something else, started us off, making

rhymes. After great efforts, amidst much laughter and profound knitting of

brows, we produced what, in the innocence of youth, we called a poem! — an

epic, on our adventure. I still preserve the old scrawl of it, in several

different youthful hands, on crumpled sheets of yellowed paper. It has little

value as poesy, but I would not part with it for autograph copies of the

masterpieces of Kipling, or Aldrich. It must have been akin to snow-madness, for I remember

that Thomas who never attempted a line of poetry before, nor since, led off

with the following stanzas: — "Four boys went off to look for sheep, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. And the trouble they had would make you weep, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. "They searched the pasture high and low, Then to Dunham's Open they tried to go. But the sky was dark and the wind did blow And the woods was dim with whirling snow. "They lost their way and got turned round, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny co'nan. It's a wonder now they ever were found. Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. "The storm howled round them wild and drear. Stoss Pond did then by chance appear. They all declared 'twas 'mazing queer. 'We're lost,' said Captain Ad, 'I fear.'" Then either Kate or Ellen put forth a fifth and sixth stanza: — "But Halse espied an old log camp, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. And into it they all did tramp, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. "'Here's beans,' said Tom. 'Here's salt,' said Ad. 'Boiled beans don't go so very bad, When nothing else is to be had. Let's eat our beans and not be sad.'" I cannot say, certainly, who was responsible for

these next stanzas, but the handwriting is a little like my own at that age. "They ate their beans and sang a song, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. And wished the night was not so long, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. "Said Ad, 'What makes that whining noise?' 'By jinks!' cried Tom, 'That's Tyro, boys!' But when he looked, without a care, In crawled a little beezling bear!" There is a great deal more, not less than twenty

stanzas; but a few will suffice. Besides, too, I shrink from presenting the

more faulty ones. To strangers they will be merely the immature efforts of

nameless young folks; but for me a halo of memories glorifies each halting

versicle. The one where the tree fell runs as follows. It was Addison's; and in

his now distant home, he will anathematize me for exposing his youthful bad

grammar. "But the night grew wild and wilder still, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. The forest roared like an old grist-mill, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. "At last there came a fearful crack! A big pine tree had broke its back. Down it fell, with a frightful smack! And missed the camp by just a snack!" Theodora alone made a stanza or two more in keeping

with that finer sentiment which the occasion might have inspired in us. "And we who sat and watched at home, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan; And wondered why they did not come, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. What dread was ours through that long night, That they had perished was our fear, Scarce could we check the anxious tear, Nor slept at all till morning light. "But safe from storm and falling tree, Co'day, co'day, co'nanny, co'nan. Their faces dear again we see, Co'day, co'day co'nanny, co'nan. They slept mid perils all unseen, Some Guardian Hand protecting well; E'en though the mighty tree trunks fell, The little camp stood safe between." After dinner, Mr. Edwards with Asa Doane went after

the sheep, and by tramping a path in advance of the flock, drove them home to

the barns. Next day Asa and Halse took a bushel basket, with a

bran sack to tie over it, and went to Adger's camp, to liberate and fetch home

the little "beezling bear," but found that bruin junior had upset the

barrel and made his escape. THE END OF BOOK FIRST. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2008

(Return to Web Text-ures)