| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

When Life Was Young At the Old Farm in Maine Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER

XXII

HIGH TIMES Truth to say, we had a pretty

"high time"

that week. When not at Tom's fort evenings, our youthful neighbors came

to our

house. Sweet corn was in the "milk;" and early apples, pears and

plums were ripe. We roasted corn ears and played hide-and-seek by

moonlight,

over the house, wagon-house, wood-shed, granary and both barns. I am inclined to believe that

the Old Squire did not

leave work enough to keep us properly out of that idleness which leads

to

mischief. For on the afternoon of the fourth day, we broke one wheel of

the ox

cart and hay rack, while "coasting" in it. There was a long slope in

the east field; and we coasted there, all getting into the cart and

letting it

run down backwards, dragging the "tongue" on the ground behind it:

not the proper manner of using a heavy cart. After we had coasted down, we

hauled the cart back

with the oxen which we yoked for the purpose. The wheel was broken on

account

of the cart running off diagonally and striking a large stone. We were obliged to own up to the

matter on the Old

Squire's return. He said little; but after considering the matter over

night,

he held a species of moot court in the sitting-room, heard all the

evidence and

then, good-humoredly, "sentenced" Addison, Halstead and myself to

work on the highway that fall till we had earned enough to repair the

wheel,

six dollars; and speaking for myself, it was the most salutary bit of

correction which I ever received; it led me to feel my personal

responsibility

for damage done foolishly. But it is not of the broken cart

wheel, or

hide-and-seek by moonlight, that I wish to speak here, but of another

diversion

next day, and of a mysterious stranger who arrived at nick of time to

participate in it. Generally speaking, Theodora did

not excel as a cook.

She was much more fond of reading than of housework and domestic

duties,

although at the farm she always did her share conscientiously. Ellen

had a

greater natural bent toward cookery. But there was one article of

food which Theodora

could prepare to perfection and that was fried pies. Such at least was

the name

we had for them; and we boys thought that if "Doad" had known how to

do nothing else in the world but fry pies, she would still be a shining

success

in life. We esteemed her gift all the more highly for the reason that

it was

extra-hazardous. Making fried pies is nearly as dangerous as working in

a

powder-mill; those who have made them will understand what this means.

I know a

housewife who lost the sight of one of her eyes from a fried pie

explosion. In

another instance fully half the kitchen ceiling was literally coated

with

smoking hot fat, from the frying-pan, thrown up by the bursting of a

pie. Let not a novice like myself,

however, presume to

descant on the subject of fried pies to the thousands who doubtless

know all

the details of their manufacture. Theodora first prepared her dough,

sweetened

and mixed like ordinary doughnut dough, rolled it like a thick pie

crust and

then enclosed the "filling," consisting of mince-meat, or stewed

apple, or gooseberry, or plum, or blackberry; or perhaps peach,

raspberry, or

preserved cherries. Only such fruits must be cooked and the pits or

stones of

plums or peaches carefully removed. The edges of the dough were wet and

dexterously crimped together, so that the pie would not open in frying. Then when the big pan of fat on

the stove was just

beginning to get smoking hot, the pies were launched gently in at one

side and

allowed to sink and rise. And about that time it was well to be

watchful; for

there was no telling just when a swelling, hot pie might take a fancy

to enact

the role of a bomb-shell and blow the blistering hot fat on all sides. After suffering from a bad burn

on one of her wrists

the previous winter, Theodora had learned not to take chances with

fried pies.

She had a face mask which Addison had made for her, from pink

pasteboard, and a

pair of blue goggles for the eyes, which some member of the family had

once

made use of for snow blindness. The mask as I remember wore an

irresistible

grin. When ready to begin frying two

dozen pies, Theodora

donned the mask and goggles and put on a pair of old kid gloves. Then

if

spatters of hot fat flew, she was none the worse; — but it was quite a

sight to

see her rigged for the occasion. The goggles were of portentous size,

and we

boys used to clap and cheer when she made her appearance. As an article of diet, perhaps,

fried pies could

hardly be commended for invalids; but to a boy who had been working

hard, or

racing about for hours in the fresh air out of doors, they were simply

delicious and went exactly to the right spot. Few articles of food are

more

appetizing to the eye than the rich doughnut brown of a fine fried pie. That forenoon we coaxed Theodora

and Ellen to fry a

batch of three dozen, and two "Jonahs;" and the girls, with some

misgivings as to what Gram would say to them for making such inroads on

"pie timber," set about it by ten o'clock. Be it said, however, that

"closeness" in the matter of daily food was not one of Gram's faults.

She always laid in a large supply of "pie timber" and was not much

concerned for fear of a shortage. They filled half a dozen with

mince-meat, half a

dozen with stewed gooseberry, and then half a dozen each, of crab apple

jelly,

plum, peach and blackberry. They would not let us see what they filled

the

"Jonahs" with, but we knew that it was a fearful load. Generally it

was with something shockingly sour, or bitter. The "Jonahs" looked

precisely like the others and were mixed with the others on the platter

which

was passed at table, for each one to take his or her choice. And the

rule was

that whoever got the "Jonah pie" must either eat it, or crawl under

the table for a foot-stool for the others during the rest of the meal! What they actually put in the

two "Jonahs,"

this time, was wheat bran mixed with cayenne pepper — an awful dose

such as no

mortal mouth could possibly bear up under! It is needless to say that

the girls

usually kept an eye on the Jonah pie or placed some slight private mark

on it,

so as not to get it themselves. When we were alone and had

something particularly

good on the table, Addison and Theodora had a habit of making up rhymes

about

it, before passing it around, and sometimes the rest of us attempted to

join in

the recreation, generally with indifferent success. Kate Edwards had

come in

that day, and being invited to remain to our feast of fried pies, was

contributing her wit to the rhyming contest, when chancing to glance

out of the

window, Ellen espied a gray horse and buggy with the top turned back,

standing

in the yard, and in the buggy a large elderly, dark-complexioned man, a

stranger to all of us, who sat regarding the premises with a smile of

shrewd

and pleasant contemplation. "Now who in the world can that

be?"

exclaimed Ellen in low tones. "I do believe he has overheard some of

those

awful verses you have been making up." "But someone must go to the

door," Theodora

whispered. "Addison, you go out and see what he has come for." "He doesn't look just like a

minister,"

said Halstead. "Nor just like a doctor," Kate

whispered.

"But he is somebody of consequence, I know, he looks so sort of

dignified

and experienced." "And what a good, old, broad,

distinguished

face," said Ellen. Thus their sharp young eyes took

an inventory of our

caller, who, I may as well say here, was Hannibal Hamlin, recently

Vice-President of the United States and one of the most famous

anti-slavery

leaders of the Republican party before the Civil War. The old Hamlin homestead, where

Hannibal Hamlin

passed his boyhood, was at Paris Hill, Maine, eight or ten miles to the

eastward of the Old Squire's farm; he and the Old Squire had been young

men

together, and at one time quite close friends and classmates at Hebron

Academy. In strict point of fact, Mr.

Hamlin's term of office

as Vice-President with Abraham Lincoln, had expired; and at this time

he had

not entered on his long tenure of the Senatorship from Maine. Meantime

he was

Collector of Customs for the Port of Boston, but a few days previously

had

resigned this lucrative office, being unwilling longer to endorse the

erratic

administrative policy of President Andrew Johnson by holding an

appointment

from him. In the interim he was making a

brief visit to the

scenes of his boyhood home, and had taken a fancy to drive over to call

on the

Old Squire. But we of the younger and lately-arriving generation, did

not even

know "Uncle Hannibal" by sight and had not the slightest idea who he

was. Addison went out, however, and asked if he should take his horse. "Why, Joseph S——

still lives here, does he not?" queried Mr. Hamlin,

regarding Addison's youthful countenance inquiringly. "Yes, sir," replied Addison. "I

am his

grandson." "Ah, I thought you were rather

young for one of

his sons," Mr. Hamlin remarked. "I heard, too, that he had lost all

his sons in the War." "Yes, sir," Addison replied

soberly. Mr. Hamlin regarded him

thoughtfully for a moment.

"I used to know your grandfather," he said. "Is he at

home?" Addison explained the absence of

Gramp and Gram.

"I am very sorry they are away," he added. "I am sorry, too," said Mr.

Hamlin, "I

wanted to see them and say a few words to them." He began to turn his

horse as if to drive away, but Theodora, who was always exceedingly

hospitable,

had gone out and now addressed our caller with greater cordiality. "Will you not come in, sir?" she

exclaimed.

"Grandfather will be very sorry! Do please stop a little while and let

the

boys feed your horse." Mr. Hamlin regarded her with a

paternal smile.

"I will get out and walk around a bit, to rest my legs," he replied. Once he was out of the buggy,

Addison and I took his

horse to the stable; and Theodora having first shown him the garden and

the

long row of bee hives, led the way to the cool sitting-room, and

domesticated

him in an easy chair. We heard her relating recent events of our family

history

to him, and answering his questions. Meantime the fried pies were

waiting and getting

cold; and when Addison and I had returned from the stable, we all began

to feel

a little impatient. Ellen and Kate set the pies in the oven, to keep

them warm;

we did not like to begin eating them with company in the sitting-room,

and so

lingered hungrily about, awaiting developments. "How long s'pose he

will

stay!" Halse exclaimed crossly; and Addison began brushing up a little,

in

order to go in and help do the honors of the house with Theodora. "He is a pretty nice old

fellow," Addison

remarked to Kate. "Have you any idea who he is?" But Kate, though born in the

county, had never seen

him. Just then the sitting-room door opened, and we heard "Doad"

saying, "We haven't much for luncheon to-day, but fried pies, but we

shall

all be glad to have you sit down with us." "What an awful fib!" whispered

Ellen behind

her hand to Kate; and truth to say, his coming had rather upset our

anticipated

pleasure; but Mr. Hamlin had taken a great fancy to Theodora and was

accepting

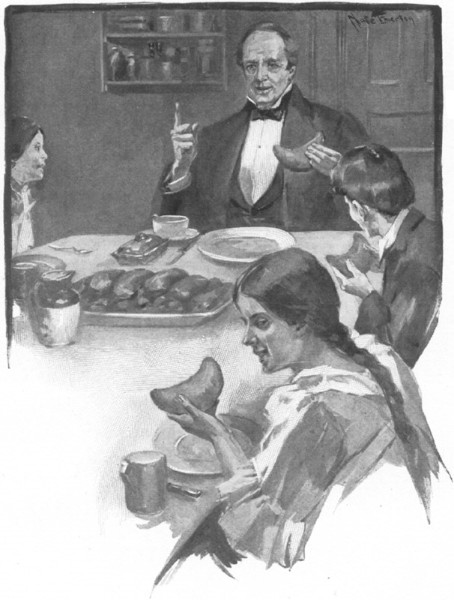

her invitation, with vast good-nature. What a great dark man he looked,

as he followed

Theodora out to the table. "These are my cousins that I

have told you

of," she was saying, and then mentioned all our names to him and

afterwards Kate's, although Mr. Hamlin had not seen fit to tell us his

own; we

supposed that he was merely some pleasant old acquaintance of Gramp's

early

years. He was seated in Gramp's place

at table and, after a

brief flurry in the kitchen, the big platterful of fried pies was

brought in.

What Ellen and Theodora had done was, carefully to pick out the two

"Jonahs" and lay them aside. We were now all gathered around. Addison

and Theodora exchanged glances and there was a little pause of

interrogation,

in case our caller might possibly be a clergyman, after all, and might

wish to

say grace. He evinced no disposition to do

so, however; and

laughing a little in spite of herself, Doad raised the platter and

assayed to

pass it to our guest. "And are these the 'fried

pies?'" he asked

with the broadest of smiles. "They resemble huge doughnuts. But I now

remember that my mother used to fry something like this, when I was a

boy at

home, over at Paris Hill; and my recollection is that they were very

good." "Yes, the most of them are very

good," said

Addison, by way of making conversation, "unless you happen to get the

'Jonah.'" "And what's the 'Jonah?'" asked

our

visitor. Amidst much laughter, this was

explained to him —

also the penalty. Mr. Hamlin burst forth in a great shout of laughter,

which

led us to surmise that he enjoyed fun. "But we have taken the 'Jonahs'

out of

these," Theodora made haste to reassure him. "What for?" he exclaimed. "Why — why — because we have

company,"

stammered Doad, much confused. "And spoil the sport?" cried our

visitor.

"Young lady, I want those 'Jonahs' put back." "Oh, but they are awful

'Jonahs!'" pleaded

Theodora. "I want those 'Jonahs' put

back," insisted

Mr. Hamlin. "I shall have to decline to lunch here, unless the 'Jonahs'

are in their proper places. Fetch in the 'Jonahs.'" Very shamefaced, Ellen brought

them in. "No hokus-pokus now," cried our

visitor, and

nothing would answer, but that we should all turn our backs and shut

our eyes,

while Kate put them among the others in the platter. It was then passed and all chose

one. "Each take

a good, deep mouthful," cried Mr. Hamlin, entering mirthfully into the

spirit

of the game. "Altogether — now!" We all bit, eight bites at once;

as it chanced no one

got a "Jonah," and the eight fried pies rapidly disappeared. "But these are good!" cried our

visitor,

"Mine was gooseberry." Then turning to Theodora, "How many times

can a fellow try for a 'Jonah' here?" "Five times!" replied Doad,

laughing and

not a little pleased with the praise. The platter was passed again,

and again no one got

bran and cayenne. But at the third passing, I saw

Kate start visibly

when our visitor chose his pie. "All ready. Bite!" he cried; and we

bit! but at the first taste he stopped short, rolled his eyes around

and shook

his head with his capacious mouth full. "Oh, but you need not eat it,

sir!" cried

Theodora, rushing round to him. "You need not do anything!" But without a word our bulky

visitor had sunk slowly

out of his chair and pushing it back, disappeared under the long table. For a moment we all sat,

scandalized, then shouted in

spite of ourselves. In the midst of our confused hilarity, the table

began to

oscillate; it rose slowly several inches, then moved off, rattling,

toward the

sitting-room door! Our jolly visitor had it on his back and was

crawling

ponderously but carefully away with it on his hands and knees; — and

the rest

of us were getting ourselves and our chairs out of the way! In fact,

the

remainder of that luncheon was a perfect gale of laughter. The table walked

clean around the room and came very carefully back to its original

position. After the hilarity had subsided,

the girls served

some very nice large, sweet blackberries, which our visitor appeared to

relish

greatly. He told us of his boyhood at Paris Hill; of his fishing for

trout in

the brooks thereabouts, of the time he broke his arm and of the doctor

who set

it so unskilfully that it had to be broken again and re-set; of the

beautiful

tourmaline crystals which he and his brother found at Mt. Mica; and of

his

school-days at Hebron Academy; and all with such feeling and such a

relish,

that for an hour we were rapt listeners.  FRIED PIES. When at length he declared that

he positively must be

going on his way, we begged him to remain over night, and brought out

his horse

with great reluctance. Before getting into the buggy,

he took us each by the

hand and saluted the girls, particularly "Doad," in a truly paternal

manner. "I've had a good time!" said he.

"I am

glad to see you all here at this old farm in my dear native state; but

(and we

saw the moisture start in his great black eyes) it touches my heart

more than I

can tell you, to know of the sad reason for your coming here. You have

my

heartiest sympathy. "Tell your grandparents, that I

should have been

very glad to see them," he added, as he got in the buggy and took the

reins from Addison. "But, sir," said Theodora,

earnestly, for

we were all crowding up to the buggy, "grandfather will ask who it was

that called." "Oh, well, you can describe me

to him!"

cried Mr. Hamlin, laughing (for he knew how cut up we should feel if he

told us

who he really was). "And if he cannot make me out, you may tell him

that

it was an old fellow he once knew, named Hamlin. Good-by." And he drove

away. The name signified little to us at the time. "Well, whoever he is, he's an

old brick!"

said Halse, as the gray horse and buggy passed between the high

gate-posts, at

the foot of the lane. "I think he is just splendid!"

exclaimed

Kate, enthusiastically. "And he has such a great, kind

heart!" said

Theodora. When Gramp and Gram came home,

we were not slow in

telling them that a most remarkable elderly man, named Hamlin, had

called to

see them, and stopped to lunch with us. "Hamlin, Hamlin," repeated the

Old Squire,

absently. "What sort of looking man?" Theodora and Ellen described

him, with much zest. "Why, Joseph, it must have been

Hannibal!"

cried Gram. "So it was!" exclaimed Gramp.

"Too bad

we were not at home!" "What! Not Hannibal Hamlin that

was

Vice-President of the United States!" Addison almost shouted. "Yes, Vice-President Hamlin,"

said the Old

Squire. And about that time, it would

have required nothing

much heavier than a turkey's feather to bowl us all over. Addison

looked at

"Doad" and she looked at Ellen and me. Halse whistled. "Why, what did you say, or do,

that makes you

look so queer!" cried Gram, with uneasiness. "I hope you behaved well

to him. Did anything happen?" "Oh, no, nothing much," said

Ellen,

laughing nervously. "Only he got the 'Jonah' pie and — and — we've had

the

Vice-President of the United States under the table to put our feet on!"

Gram turned very red and was

much disturbed. She

wanted to have a letter written that night, and try to apologize for

us. But

the Old Squire only laughed. "I have known Mr. Hamlin ever since he was

a

boy," said he. "He enjoyed that pie as well as any of them; no

apology is needed." |