| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

When Life Was Young At the Old Farm in Maine Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER III

MONDAY AT THE OLD FARM "I shall expect you to work with us on the farm,

'Edmund,'" grandfather said to me after breakfast. "But you may have

this forenoon, to look about and see the place. Enjoy yourself all you

can." The robins were singing blithely in the orchard. I

went thither and I think it was four robins' nests which I found in as many

different apple trees, one with three, two with four and one with five blue

eggs. Is there anything prettier than the eggs of a robin, in the eyes of a

boy? As I climbed the orchard wall to cross the road, a

milk snake was sunning on the loose stones among the raspberry bushes, the

first I had ever seen; and I bear witness that the ancestral antipathy to the serpent

leaped within me instantly. I beat his head without remorse, ay, pounded his

tail, too, which wriggled prodigiously, and chopped his body to pieces with

sharp stones. This sorry victory achieved, I set off across the

fields to the west pasture and thence descended to the west brook, where I saw

several trout in a deep hole beneath the decayed logs of a former bridge. With

a mental resolve to come here fishing, as soon as I could procure a hook and

line, I continued onward through a low, swampy tract overgrown with black alder

and at length reached the "colt pasture," upon a cleared hill. Here a

handsome black colt, along with a sorrel and a white one, was feeding, and at

once came racing to meet me, in the hope of a nib of provender, or salt.

Continuing my voyage of discovery, I came to a tract of woodland beyond the

pasture through which a cart road led to a clearing where there was a small old

house, deserted, and also a small barn. This, as I had yet to learn, was the

"Aunt Hannah lot," an appendage of the farm, which had come into

grandfather's possession from a sister, my great-aunt of that name. Save a

field of oats, the land here was allowed to lie in grass and remain otherwise

uncultivated. Beyond this small outlying farm, there was a dense body of

woodland, which I did not then attempt to penetrate, but made a circuit to the

northward through pasture land and young wood for half a mile or more, and by

and by crossed the road, looking along which to the northwest, I could see the

farmhouses of several of our neighbors. Still farther around to the north rose a bold, rocky,

cleared hill which I concluded was the sheep pasture. In a wet run along the

foot of the hill was a stretch of what looked to be low, reddish, brushy grass,

which I ascertained later was the "cranberry swale." Beyond it to the east, a long field curved around the

foot of the sheep pasture; and on the far side of this field there was woodland

again, descending first to the valley of the east brook where lay the

"Little Sea," then ascending a rugged hill. A boy, like a bee, must needs take his bearings

before he can feel quite at home in a new place. I crossed the valley and

climbed the wooded hill beyond, a distance of nearly a mile and a half from the

farmhouse. Formerly there had been a grand growth of pine here; and there were

still a few pine trees. Numbers of the old stumps and stubs were of great size.

This rugged ridge bore the name of Pine Hill. From the summit I gained a fine

view of the country around, with its farms and forest tracts, and of the

Pennesseewassee stretching away to the southward; also of the White Mountains

in the northwest; while on the other side of the hill to the east and

southeast, lay an extensive bog and another smaller lake, or pond, known as

North Pond. For half an hour or more I sat upon a pine stump and

pored over the geography of the district with much boyish interest, noting

various hills, farmhouses and other landmarks concerning which I determined to

inquire of Addison. At length, beginning to feel hungry and bethinking

myself that it must be getting toward noon, I descended from my perch of

observation, and made my way homeward, although it did not seem very much like

home to me as yet. The tramp had done me good in the way of satisfying my "bump

of location." Reaching the house in advance of the noon hour, I

went out with Theodora to see the eaves swallows again. We counted fifty-seven

nests in a row, each resembling very much a dry cocoanut shell, with a

swallow's head looking out at a little hole on the upper side. Dora pointed out

the nest of one pair which had experienced much ill luck. Three times the nest

had fallen. No sooner would they finish it and have an egg or two, than down it

would fall on the stones below. But their misfortunes had finally taught the

little architects wisdom. They brought hair from the barnyard and mixed it with

their mud, after the manner of mortar, and so built a nest which successfully

adhered. All this Theodora told me as we stood watching them,

coming and going with cheery, ceaseless twitterings. "And I think they've got a kind of reason about

such things," Theodora added with a certain tone of candid concession.

"Although Gram says it is only instinct. She doesn't like to have any one

say that animals or birds reason; she thinks it isn't Scriptural." Just then Ellen came out with the dinner-horn which,

after several dissonant efforts, she succeeded in sounding, to call the Old

Squire and the boys from the field. Theodora and I were so greatly amused at

the odd sound that we burst out laughing; and Ellen, hearing us, was a good

deal mortified. "I don't care!" she exclaimed. "It goes awfully

hard; I haven't got breath enough to quite 'fill' it; and my lip isn't hard

enough. Ad says it takes practice to get up a lip for horn blowing." Theodora tried it, and elicited a horrible blare. I

did not succeed much better; something seemed to be lacking in my lip, or my

lungs. It required a tremendous head of wind to make the old tube vibrate; at

last, I got it started a-roaring and made the whole countryside hideous with an

outlandish sort of blast. Theodora begged of me to desist. "We shall have the neighborhood aroused and

coming to see what the matter is," she said. I was so much elated with my

success, however, that I blew a final roar; and just then Addison, Halstead,

grandfather and two hired men came upon the scene, over the wall from the field

side. "What on earth are you trying to do with that

horn?" Halstead called out. "Do you think we are deaf? I never heard

such a noise!" "It is only our new cousin getting up his

lip," said Ellen, scarcely able to speak for laughing. Grandfather told me that if they ever organized a

brass band thereabout, I should have the big French horn to play, for I seemed

to have the makings of a tremendous lip. All these little incidents of my first

few days at the farm are enduringly fixed in my memory. The day proved a warm one; and after dinner I went

into the front sitting-room and looked at the old family pictures:

grandfather's father and mother in silhouette, General Scott's triumphant entry

into the city of Mexico, Jesus disputing with the Doctors, Martin Luther,

George Washington and several daguerreotypes of my uncles and aunts, framed and

hung on the wall. Next I read the battle parts of a new history of the War, by

Abbott. Erelong grandfather came in for a nap on the lounge;

and I found that Addison and Halstead were hitching up old Sol and loading bags

of corn into the farm wagon, to go to mill. They told me that the grist mill

was three miles distant and invited me to go along with them. We set off

immediately, all three of us sitting on the seat, in front of the bags.

Halstead wanted to drive; but Addison had taken possession of the reins and

kept them, although Halstead secured the whip and occasionally touched up the

horse, contrary to Addison's wishes; for it proved a very hilly road. First we

descended from the ridge on which the home farm is located, crossed the meadow,

then ascended another long ridge whence a good view was afforded of several

ponds, and of the White Mountains in the northwest. Descending from this height of land to the westward

for half a mile, we came to the mill, in the valley of another large brook. It

was a weathered, saddle-back old structure, situated at the foot of a huge dam,

built of rough stones, like a farm wall across the brook, and holding back a

considerable pond. A rickety sluice-way led the water down upon the water-wheel

beneath the mill floor. When we arrived there was no one stirring about the

mill; but we had no more than driven up and hitched old Sol to a post, when two

boys came out from a small red house, a little way along the road, where lived

the miller, whose name was Harland. "There come Jock and George," said Addison.

"Maybe the old man isn't at home to-day. "Where's your father?" he called out, as

the boys drew near. "Gone to the village," replied the larger

of the two, who was apparently thirteen or fourteen years of age. "We want to get a grist ground," Addison

said to them. "What is it?" they both asked. "Corn," replied Ad. "If it's only corn, we can grind it," they

said. "Take it in so we can toll it. Pa said we could grind corn, or oats

and pease; but he won't let us grind wheat, yet, for that has to be

bolted." We carried the bags into the mill; there were three

of them, each containing two bushels of corn; and meantime the two young

millers brought along a half-bushel measure and a two-quart measure. "It's two quarts toll to the bushel, ye

know," said Jonathan, the elder of the two. "So I must have two

two-quart measurefuls out of every bag." He proceeded to untie the bags

and toll them, dipping out a heaped measureful. "Here, here," said Addison, "you must strict

those measures with a square; you're getting a good pint too much on every

one." "All right," they assented, and producing a

piece of straight-edged board, stricted them. "Have to watch these millers a little,"

Addison remarked. "And I guess, Jock, you had better not toll all the bags

till you see whether there's water enough to grind all of it." "O, there's water enough," said they.

"There's a whole damful." They then poured the first bagful into the hopper

over the millstones, and went to hoist the gate. It was a very primitive, worn

piece of mechanism, and hoisting it proved a difficult task. Addison and

Halstead went to help them. At length they heaved the gate up; the water-wheel

began to turn and the other gear to revolve, making a tremendous noise. I

climbed down beneath the mill, at the lower end, to see the water-wheel

operate. The wheel and big mill post turned ponderously around, wabbling

somewhat and creaking ominously. By the time I went back into the mill, above,

the first bagful of corn was nearly ground into yellow meal, which came out of

the stones into the meal-box quite hot from the molinary process. Addison was

dipping the meal out and putting it up in the empty bag. "Is it fine enough?" Jock called out.

"I can drop the stone a little, if ye say so. We will grind it just as ye

want it." Presently something went through the millstones that

made an odd noise; and the young miller, George, accused Halstead of throwing a

pebble into the hopper. They had a dispute about it, and George complained that

such a trick might spoil the millstones. Another bagful was poured into the hopper and ground

out; and then Addison and I brought along the third bagful. "Hold on there," said Jock. "I haven't

tolled that bag." We thought that he had tolled it. "No," said both Jock and George. "You

said not to toll that last bag till we saw whether there was water enough to

grind it." "But you declared that there was water enough,

and tolled it!" cried Halstead. Addison and I could not say positively whether they

had tolled it or not; and they appeared to think that it had not been tolled.

The point was argued for some moments; finally it was agreed to compromise on

it and let them have one measure of toll out of it. So there was two quarts of

loss or gain, whichever party was in error. When the last bagful was nearly ground and the hopper

empty, all save a pint or so, Jock and George ran to shut the gate and stop the

mill. "Hold on!" cried Addison. "That isn't

fair. There's two quarts in the stones yet; we shall lose all that on top of

toll." "But we must shut down before the corn is all

through the stones!" cried Jock, "or they'll get to running fast and

grind themselves. 'Twon't do to let them get to running fast, with no corn

in." "Well, don't be in such haste about it,"

urged Addison. "Wait a bit till our grist is nearer out." They waited a few moments, but were very uneasy about

the stones, and soon after the last kernels of corn had disappeared from the

hopper, they pulled the ash pin to let the gate fall. It was then discovered

that from some cause the gate would not drop. The boys thumped and rattled it.

But the water still poured down on the wheel. By this time the meal had run

nearly all out of the millstones and they revolved more rapidly. The young

millers were now a good deal alarmed, and, running out, climbed up the dam and

looked into the flume, to see what was the matter with their gate. "It's an old shingle-bolt!" shouted Jock,

"that's floated down the pond! It's got sucked in under the gate and holds

it up! Fetch the pike-pole, George!" George ran to get the pike-pole; and for some moments

they tried to push, or pull, the block out. But it was wedged fast and the

in-draught of the water held it firmly in the aperture beneath the gate. It was

impossible to reach it with anything save the pike-pole, for the water in the flume

over it was four or five feet deep. Meantime the old mill was running amuck inside. The

water-wheel was turning swiftly and the millstone was whirling like a buzz saw.

After every few seconds we could hear it graze down against the nether stone

with an ugly sound; and then there would fly up a powerful odor of ozone. Jock and George, finding that they could not shut the

gate, came rushing into the mill again in still greater excitement. "The stones'll be spoilt!" Jock exclaimed.

"We must get them to grinding something." He ran to the little bin of about a bushel of corn

where the old miller kept his toll and where they had put the toll from our

bags. This was hurriedly flung into the hopper and came through into the

meal-box at a great rate. It checked the speed in a measure, however, and we

took breath a little. "You had better keep the mill grinding till the

pond runs out," Addison advised. "I would," replied Jock, "but that's

all the grain there is here." It was evident that the mill must be kept grinding at

something or other, or it would grind itself. It would not answer to put in

pebbles. Ad suggested chips from the wood yard; and George set off on a run to

fetch a basketful of chips to grind; but while he was gone, Jock bethought

himself of a pile of corncobs in one corner of the mill; and we hastily

gathered up a half-bushel measureful. They were old dry cobs and very hard. "Not too fast with them!" Jock cautioned.

"Only a few at a time!" By throwing in a handful at a time, we reduced the

speed of the stones gradually, and then suddenly piling in a peck or more

slowed it down till it fairly came to a standstill, glutted with cobs. The

water-wheel had stopped, although the water was still pouring down upon it; and

in that condition we left it, with the miller boys peeping about the flume and

the millstones and exclaiming to each other, "What'll Pa say when he gets

back!" That was my first experience in active milling

business, and it made a profound impression on my mind. But we were not yet home with our grist, by a great

deal! Halstead had resented it because he had not been able to drive the horse

on the outward trip. While Addison and I were throwing in the last bag, he

jumped into the wagon and secured the reins. Not to have trouble, Addison said nothing

against his driving; and we two walked up the long hill from the mill, behind

the wagon. Reaching the summit, we got in and Halstead started to drive down

the hill on the other side. As I was a stranger, he wished me to think that he

was a fine driver and told me of some of his exploits managing horses.

"There's no use," said he, "in letting a horse lag along down

hill the way the old mossbacks do around here. They are scared to death if a

horse does more than walk. Ad won't let a horse trot a single step on a hill,

but mopes and mopes along. I've seen horses driven in places where they know

something, and I know how a horse ought to go." In earnest of this opinion, he touched old Sol up,

and we went down the first hill at such a pace, that I was glad to hold to the

seat. "You had better be careful," said Addison.

"Drive with more sense, if you are going to drive at all — which you are

not fit to do," he added. Out of bravado, I suppose, Halstead again applied the

whip and we trundled along down the next hill at a still more rapid rate. "Now Halse, if you are going to drive like this,

just haul up and let me walk," Addison remonstrated, more seriously. But

Halstead would not stop, and, touching the horse again, set off down the last

hill before reaching the meadow, at an equally smart pace. It is likely, however, that we might have got down

without accident; but the road, like most country roads, was rather narrow and

as we drew near the foot of the hill, we suddenly espied a horse and wagon

emerging from amongst the alder clumps through which the road across the meadow

wound its way, and saw, too, that a woman was driving. "Give us half the road!" Halstead shouted.

But the woman seemed confused, as not knowing on which side of the road to turn

out; she hesitated and stopped in the middle of the road. Perceiving that we were in danger of a collision,

Addison snatched the reins and turned our horse clean out into the alders; and

the off hind wheel coming violently in contact with an old log, the transient

bolt of the wagon broke. The forward wheels parted from the wagon body, and we

were all pitched out into the brush, in a heap together. The bags of meal came

on top of us. Halstead had his nose scratched; I sprained one of my

thumbs; and we were all three shaken up smartly. Addison, however, regained his

feet in time to capture old Sol who was making off with the forward wheels. The woman sat in her wagon and looked quite dazed by

the spectacle of boys and bags tumbling over each other. "Dear hearts," said she, "are you all

killed?" "Why didn't you turn out!" exclaimed

Halstead. "I know I ought to," said the woman,

humbly, "but you came down the hill so fast, I thought your horse had run

away. I was so scared I didn't know what to do." "You were not at all to blame, madam," said

Ad. "It was we who were at fault. We were driving too fast." We contrived at length to patch up the wagon by tying

the "rocker" of the wagon body to the forward axle with the rope

halter, and reloading our meal bags, drove slowly home without further

incident. Addison, having captured the reins, retained possession of them, much

to my mental relief. Halstead laid the blame alternately to the woman and to

Addison's effort to grab the reins. "Now I suppose you will go home and

tell the old gent that I did it!" he added bitterly. "If you had let

the reins alone, I should have got along all right." Addison did not reply to this accusation, except to

say that he was thankful our necks were not broken. As we drove into the

carriage house, Gramp came out and seeing the rope in so odd a position, asked

what was the matter. "The transient bolt broke, coming down the

Sylvester hill," Addison replied. "It was badly worn, I see. If you

think it best, sir, I will take it to the blacksmith's shop after work,

to-morrow." "Very well," Gramp assented; and that was

all there was said about the accident. It had been a long day, but my new experiences were

far from being over. A boy can live a great deal during one long May day. After

supper I went out to assist the boys with the farm chores, and took my first

lesson, milking a cow and feeding the calves. The latter were kept tied in the

long, now empty hay-bay of the east barn. I had already been there to see them;

there were ten of them, tied with ropes and neck-straps along the sides of the

bay to keep them apart. Weaned, or unweaned, they were fed but twice a day,

and from six o'clock in the morning to six at night is a very long time for a

young and rapidly growing calf to wait between meals. As early as four o'clock

in the afternoon those calves would begin to bawl for their supper; by half

past five one could hardly make himself heard in the barn, unless there chanced

to fall a moment's silence, while the hungry little fellows were all catching

breath to bleat again. Then they would all peal forth together on ten different

keys. How those old bare walls and high beams would

resound! Blar-r-rt! Blaw-ar-ar-ah-ahrt! Blah-ah-aht! Bul-ar-ah-ahrt! There were

eager little altos, soaring sopranos, high and importunate tenors that rose to

the roof and drowned the twitter of the happy barn-swallows. Addison, Halstead, Theodora and Ellen, who had come

to the farm before me, knew all the calves by sight and had named them. There

was Little Star, Phil Sheridan, Black Betty, Hooker, Nut, Little Dagon, Andy

Johnson and Babe. I do not recollect the others, but have particular reason to

remember Little Dagon. At the time I made the acquaintance of this

broad-headed Hereford calf he was five weeks old, and the soft buds of his

horns were beginning to show in the curly hair of his forehead. His color was

dark red, except for a milk-white face, two white feet, a white tassel on his

tail, and a little belt of white under his body. Grandfather had unexpectedly

sold this calf's mother, a fine, large, line-backed cow, to a friend at the

village on that very morning. The old gentleman kindly showed me how to milk and

how to hold the pail, then gave me a milking-stool and sat me down to milk

"Lily-Whiteface." She was not a hard milker, but it did seem to me

that after I had extracted about three quarts of milk, my hands were getting

paralyzed. Halstead, who sat milking a few yards away, had, meanwhile, been

adding to my troubles by squirting streams of milk at my left ear, till Gramp caught

him in the act and bade him desist. The old gentleman presently finished with his two

cows, and went away with his buckets of milk toward the house. Then, with

soothing guile which I had not yet learned to detect, Halstead offered to

finish milking my cow for me. I was glad to accept the offer. My untrained

fingers were aching so painfully that I could now hardly draw a drop of milk.

My knees, too, were tremulous from my efforts to clasp the pail between them. "It made mine ache at first," said Halstead

with comforting sympathy as he sat down on my stool and took my pail between

his knees. I stood gratefully by, and after a few moments he looked up and

said, "While I finish milking your cow, you run over to the west barn and

get Little Dagon. He is dreadfully hungry. His mother was sold this morning,

and we have got to teach him to drink his milk to-night." "He had better not try to lead that calf!"

Addison called out from his stool, at a distance. "Why not?" Halse exclaimed. "Oh, he

can lead him all right. All he has to do is to untie the calf's rope from the

staple in the barn post. He will come right along, himself." It seemed very simple as Halstead put it, and I

started off at once. Addison said no more; he gave me an odd look as I hastened

past him, but I hardly noticed it at the time. Little Dagon was making the rafters re-echo as I

entered the bay. When he saw me, he jumped to the end of his rope and fairly

went into the air. He had sucked the bow-knot of the rope till it was as

slippery as if soaped, and when I strove to untie it, he grabbed my hands in

his mouth. At length I untied him and then with a clatter on the loose boards,

we went out of the hay-bay, pranced across the barn floor and out at the great

doors. No one has ever explained satisfactorily what that

instinct is which guides young animals unerringly back home, or in the

direction of their kin. Hungry Little Dagon, tied up in the barn, could hardly

have noted with eyes or ears the direction in which his mother had been driven

away; but as soon as we were out at the barn doors, instead of rushing to the

other barn, where he had hitherto found his mother night and morning, the

rampant little beast headed straight past the house and down the lane to take

the road for the village. A man could have held him without difficulty. I was

in my thirteenth year, and may have weighed seventy-five pounds, but did not

have weight enough. In the exuberance of his young muscle, Little Dagon erected

his tail and made a bolt in the direction which instinct bade him take. My one chance of holding him would have been to noose

the rope about his nose and seize him close by the neck, at the start; but this

I did not understand, and, in fact, had no time to study the problem. I clung

to the end of the rope, and away we went. I was not leading the calf. Little

Dagon was leading me. First I took one long step, and then such strides as I

had never made before. Halstead and Addison had jumped up from their

milking-stools and come to the barnyard bars. "Hold him! Hold him!"

they shouted. "Don't let him get away!" Grandfather, too, had now come to the kitchen door.

"Hold him! Hold that calf!" he called out, and I clung to the knot in

the end of the rope, with determination. In a moment Little Dagon was towing me down the long

lane to the road. The gate stood open, and out we went into the highway, on the

jump. There, however, the calf pulled up short, to smell the road. I tried to

catch the strap round his neck and turn him back, but he seized my arm in his

mouth to suck it; and being unused to calves, I was afraid he would bite me.

When I attempted to lead him about, that eager impulse to find his mother again

possessed him, and away he ran down the long orchard hill. I do not now see how I contrived to hold on to the

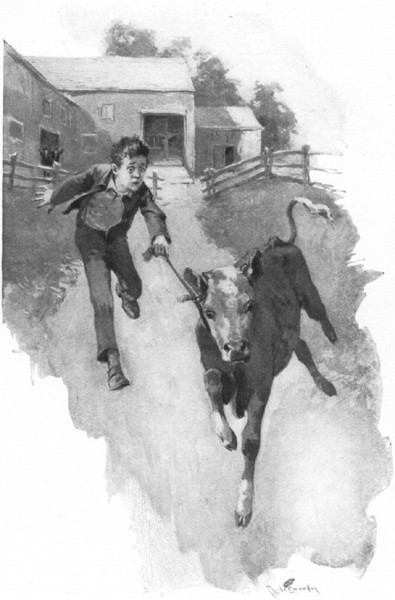

rope, but I remember thinking that if I let go Addison and Halstead would laugh

at me, and that Gramp would blame me. We raced down that long hill, my feet seeming hardly to touch the ground, and struck a level, sandy stretch at the foot of it. The sand felt queer to the calf's feet, and he stopped to smell it. By this time I was badly out of breath, but I turned his head homeward and began towing him back. He sulked, but took a few steps with me. Then he gave a sudden wild prance into the air, headed round and started again. I could not hold him, and on we went, a long run this time, until we came to the bridge over the meadow brook. There the planks proved a new wonderment to the calf, and he pulled up to smell them.  WHEN I LED LITTLE DAGON. Just then there appeared in the road ahead Theodora

and "Aunt Olive Witham," a working woman, who came every spring and

fall to help grandmother clean house and to do the year's spinning. Theodora

had been to the Corners that evening, to summon her. "Oh, help me stop him!" I panted. "For

pity's sake, catch hold of this rope! He is running away with me! I can't hold

him!" Theodora edged across the bridge to bear a hand; but

"Aunt Olive" knew calves, or thought she did. "Boss-boss-boss!" she crooned to the calf,

and extending her hand, walked straight to his head to get him by the ears.

This may have been the proper thing to do, but it did not work well that time.

Little Dagon suddenly looked up from his snuffing of the planks, and for some

reason his young eyes distrusted "Aunt Olive." He bounded aside and began again to run. I was

clinging fast to the rope, and Aunt Olive and I collided. Aunt Olive, in truth,

recoiled nearly off the end of the bridge; I was jerked onward. Little Dagon

had learned that he could pull me, and I might as well have tried to hold a

locomotive. Theodora ran a few steps after us, trying loyally to succor me.

Aunt Olive stood endeavoring to recover her breath; ordinarily she was energy

personified, but for the instant stood gasping. Beyond the meadow there was a hill, and going up that

hill I came very near mastering the calf; but after a hard tussle he gained the

top in spite of me and ran on, over descending ground, where the road passed

through woodland. We were now fully a mile and a half from home. Thus far I had

held on, but strength and breath were about gone. I was panting hard, and

actually crying from mortification. Now, however, I saw a horse drawing a light wagon

coming along the road. A well-dressed elderly man was driving. I called out to

him to aid me. If I had known who he was, I might have been less unceremonious.

"Oh, help me stop him!" I cried. "Do help me stop him! I can't

hold him!" The stranger reined his horse half round across the

road, and Little Dagon ran full against the horse's fore legs and stopped to

sniff again. The elderly gentleman got out quickly. "Did the calf run away with you, my son?"

he asked, smiling at my heated and tearful appearance. "Yes, sir," I replied, panting. "Well, well, you have had a hot run, haven't

you?" and he gave me several sympathetic pats on the shoulder. "How

far have you come, all so fast?" "I came from Grandpa S.'s," I replied, as

steadily as I could, for I was sadly out of breath. "Your grandfather is Joseph S.?" queried

the elderly man. "Yes, sir," I replied. "I have just

come there to live." "Ah, yes," commented my new acquaintance.

"I know your grandpa very well. I am on my way to call on him. Now let's

see. How shall we manage? Do you think that you could sit in the back part of

my wagon and lead the calf, if I were to drive slowly?" "I'm afraid he would pull me out!" I

exclaimed. "Not if we both hold the rope, I think,"

remarked the elderly man, still smiling broadly. "I will reach back with

one hand and help you hold him." After much pulling, hauling and manœuvring, Little

Dagon was brought to the back of the wagon. I then sat in the rear, with my

feet hanging out, and took the line; and my new friend gave hand to the rope

over the back of the seat. The horse started to walk, and Little Dagon was

drawn after; but the perverse little creature settled back in his strap till

his tongue hung out. The stranger laughed. "It seems that we cannot lead a calf unless the

calf pleases," he said. "Can you think of any better way, my

son?" I thought hard, for I was ashamed to put my new

acquaintance to so much trouble and have nothing to suggest. At last, I said,

with some diffidence, that we might tie the calf's legs with the rope and put

him in the rear of the wagon, while I walked behind. "That appears to be a practical

suggestion," the stranger remarked. "Do you think you can tie his

legs?" I answered that I believed I could if I had the calf

on the ground. "Well, sir," said he, with a whimsical glance at me,

"I think I can capsize the calf and hold him down, if you will agree to

tie his legs within a reasonable time." I said I would try; and while I held the rope the

stranger alighted, seized the calf suddenly by the legs, and threw it down on

its side. Little Dagon struggled pluckily, but my new ally held fast and called

on me to do my part. After some hard picking at the knot, I untied the rope

from the neck-strap, then tied the calf's legs into a bunch and crisscrossed

the rope. "Pretty well done, my son, pretty well

done," was the encouraging comment of my new friend. "Now I will take

him by the head while you seize him by the tail, and we will hoist him into the

wagon." Before we could do so, however, we heard a sudden

rattle of wheels close at hand, and glancing around, I saw Gramp and Addison

with old Sol in the express wagon. They had harnessed and given chase; Theodora

and Aunt Olive, whom they met, had adjured them to drive fast if they hoped

ever to overtake me. Grandfather, on seeing who was helping me, exclaimed,

"Why, Senator, how do you do, sir! My calf appears to be making you a

great deal of trouble." In fact, my friend in need was none other than Hon.

Lot M. Morrill, who had been Governor of Maine for three terms in succession,

and was now United States Senator. Grandfather and he had been acquaintances

for forty years or more; and I have inferred since that the object of Mr.

Morrill's visit on this occasion was in part political. At this particular time

the Senator was "looking after his political fences" — although this

phrase had not yet come into vogue. Grandfather and Mr. Morrill immediately drove home

together, leaving Addison and me to put the calf in the express wagon and follow

more slowly. Senator Morrill at this time gave me the impression

of being a man oppressed by not a little anxiety, and inclined to be

dissatisfied with his career. As distinctly as if it were yesterday, I recall

what he said to me the next morning as he was about to drive away. "My

son," said he impressively, "don't you be a politician. Be a farmer

like your grandfather. He has had a happier life than I have had." As it chanced, I was soon to have further experience

with headstrong young cattle. |