VIII

KETTÉ-ADENE

WAY down in the heart of the Maine woods

there rises

a mountain that is in truth a chieftain among peaks. To be sure it is

not the

biggest thing in mountains, not even in the East. Mount Washington and

several

of its brethren in the White Hills are greater in stature, and they in

turn are

juniors to many a summit among the mountains of North Carolina. Yet it

is

certainly to Maine that we must turn for the most imposing mountain

east of the

Rockies. Even the Indians of the Penobscot recognized its dignity when

they

christened it Ketté-Adene — the

preeminent.

Nor were white men any less impressed from the day when the mountain

came

within their horizon, and, adopting the Abenaki name, it became, and

still

remains, Ktaadn — the

prince of the Appalachians.

But who in New England knows Ktaadn?

Relatively few,

even among the mountaineering enthusiasts, have seen it other than

from afar.

Thousands of summer vacationists know the canoe routes of Maine to a

few

hundred who have ever set foot upon the serrated crest of that State's

great

mountain. If Ktaadn were in Switzerland, or even in our own Western

country, it

is safe to say that it would long ago have been prominently on the

map, and

actively boomed as a tourist attraction. That is not saying that Ktaadn

is a

Matterhorn or a Mount Rainier, but in its way it is just as

distinguished a

pile, and it is in no sense extravagant to claim for it charms that are

superior to many a mountain that is a celebrity in some other locality.

Ktaadn has been so neglected, even by its

own State,

that it would almost seem as if the people cherished a belief in their

inherited tradition of Pamola's curse, and dreaded to draw upon

themselves the

displeasure of that evil genius of the heights by so much as a

threatened

invasion of her solitudes. Small wonder, perhaps, if this indeed be

so, for

when did the mountain receive with hospitality any early visitor of

distinction?

Charles Turner, Jr., the Boston surveyor,

who, with a

party of Bangor friends, made the first known ascent in 1804, must have

caught

the old demon napping, for fair weather favored them. But she was

distinctly

on her guard when such eminent publicity men as Edward Everett Hale,

Thoreau,

and Theodore Winthrop attempted to make copy out of her retreat,

wrapping the

summit in a sulking cloud on each of these occasions, and thwarting

their

explorative inclinations.

Be the reasons what they may, the fact

remains, that

Ktaadn's glories are but little better known to-day than they were in

those

days, along about the middle of the last century. It remains to-day as

it was

even in 1860 when Theodore Winthrop termed it "the best mountain in the

wildest wild to be had on this side the continent." To some its very

remoteness and inaccessibility are added charms. One may not ride gayly

by automobile

to the base of this mountain. It is only gained by toil. From the south

and

west the customary approach is a sporty progress by canoe, with a

two-days

camping-hike at the end. The alternatives from this side are a

twenty-five-mile

tramp in over the Millinocket tote road from the railroad on the south,

or an

automobile drive from the southern end of Moosehead Lake to Ripogenus

Dam at

the foot of Chesuncook Lake, followed by an all-day walk on the river

trail to

the boarding-camps on Sourdnahunk Stream. From the east one may,

indeed, ride

on a four-wheeled rig to within a dozen miles of the summit. It is safe

to say,

however, that those final miles afoot under a heavy pack would be

easier than

the twenty-odd awheel along the lumber road.

Once upon a time Professor Hamlin,

geologist of

Harvard College, wrote enthusiastically of the day when a railroad

should be

built from Bangor to within a three-days drive of the mountain on the

east.

That was in 1879. When that happy day should arrive he foresaw good

carriage

roads leading to Ktaadn Lake, a hotel upon its shore, with the mountain

in full

view, a bridle-path thence to another hostelry which should nestle

beside the

little Chimney Pond in the Great Basin, only three miles or less by the

trail,

and directly beneath the peak itself. To-day two railroads run out from

Bangor

along that side, one a whole day's wagon-journey nearer to the mountain

than

the point that Professor Hamlin had in hopes. There are in truth roads

thence

to Ktaadn Lake, but not by any courtesy could they be regarded as tame

enough

for carriages, and the hotels are still in the dream stage. Is it to be

wondered at, then, that there are scarcely two hundred visitors to the

mountain

from all sides in any year, according to the most generous estimates?

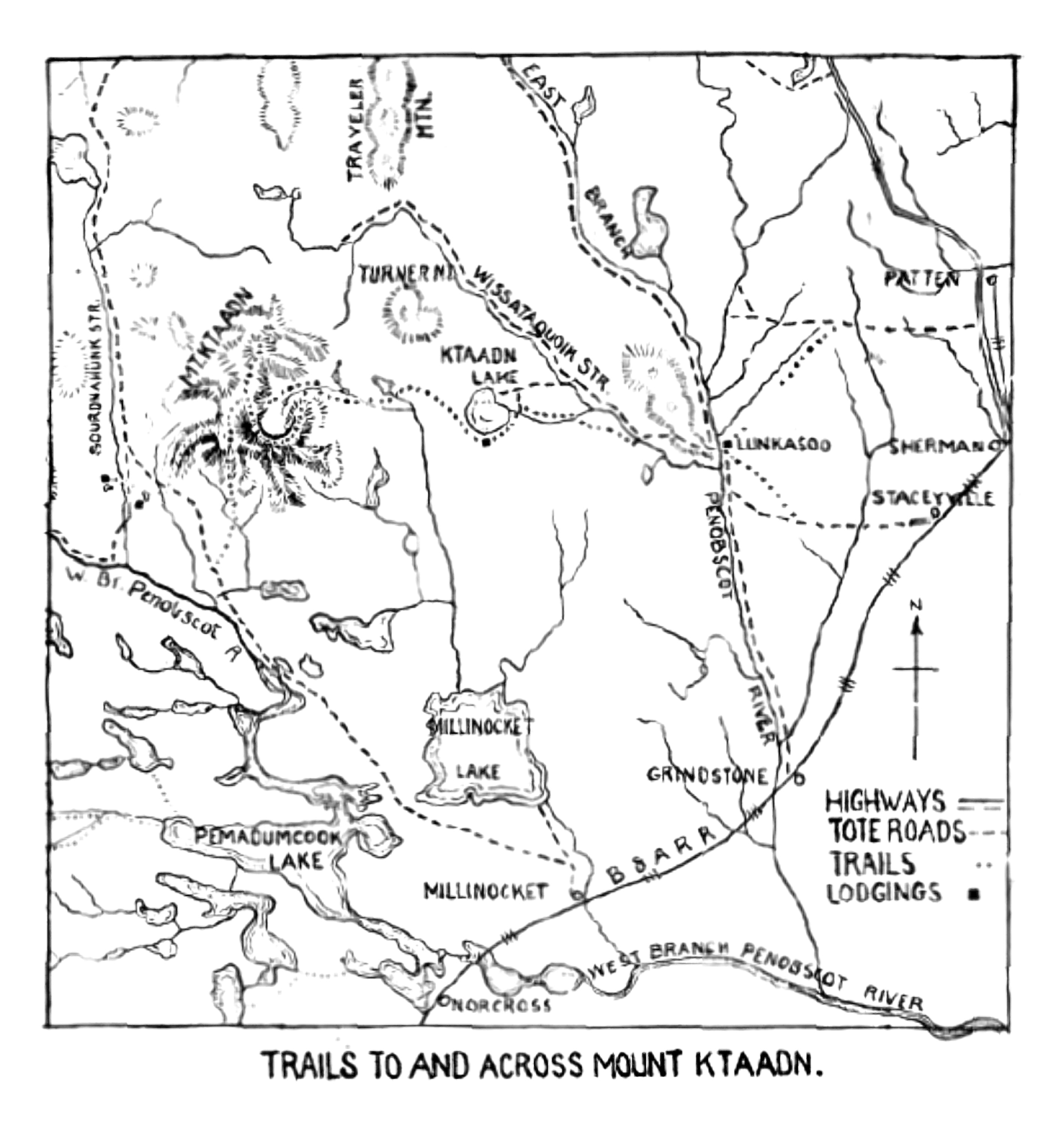

But the way is open to the tramper by tote

road and

trail from the railroad at Stacy-vile to the summit, and for those who

do not

dread a camping-pack it is a pleasant two or three days' jaunt. Not

many, if on

pleasure bent, would care to push through from railroad to mountain in

a single

day. It has been done, but twenty-seven northern Maine miles

constitute a

thoroughly full day's toil for one on foot, especially when toting

upward of

thirty-five pounds dead weight. Happily such a forced march is not

necessary. Plenty

of good camping-places lie along the way, and there are also two

boarding-camps, conveniently located, where lodging can be had.

It was about 1846 that the first trail was

cut

through to the mountain from the eastern settlements. That was built by

"Parson

"Keep, the pioneer preacher of the Aroostook, a man who appreciated

that

this vast granite bulk was of value to his State as an attraction of

great

merit, and even the Legislature of that day seemed to recognize this

also, for

it granted the parson two hundred acres of wild land on the shore of

Ktaadn

Lake in compensation for his labors. For a decade or more that trail

was kept

open and a good deal used, several women having been known to make the

ascent

that way soon after it was built.

In the early seventies lumbering

operations

obliterated this landmark, but a new trail to the Great Basin was

almost immediately

laid out, a feature that the Keep Trail, singularly enough, avoided,

its route

being to the southeast side. That, too, disappeared, though it was

restored,

and partly relocated, by the Appalachian Mountain Club in 1897', only

to be

once more lost, this time through disuse. Then came Dr. George G.

Kennedy's

party of botanical explorers from Boston in 1900, who cut yet another

route to

the Basin, where they built a tidy cabin, but this suffered no better

fate

than any of the rest, for Nature swiftly heals all such scars if man

but

withdraws for a bit. Three years after Dr. Kennedy's party a local

guide named

Rogers cut a trail from Sandy Stream Pond to the Basin, and it was

partly on

those lines that the Appalachian Club's path of 1916 was cut, the hope

being

that, with the greatly increased interest in walking as a pastime, it

might be

kept open, thus affording a through route across the mountain to and

from the

West Branch and Moosehead Lake.

From the south and west Ktaadn bulks

large, and its

ascent from those sides is a long, hard grind. From the east its

proportions

are no less vast, but in form it is far more striking. Although Turner

thought the

mountain unapproachable from the east, owing to its steepness, it is in

fact

the easiest route, with only one sharp pitch of about eight hundred

feet in

elevation, to surmount the Basin walls, and that far from difficult. On

that

side the beauty of the mountain first reveals itself at the brink of

the

Stacyville plateau. From that angle its southernmost summits group

themselves

into a steep crater-indented cone, which might well lead one to think

that it

was a volcano that stood off there before him. From the brink of the

plateau,

where the fields of the Stacyville Plantation end, an unbroken hardwood

forest

stretches out to the East Branch of the Penobscot.

For six miles the tote road and trail lead

across

this old flood plain, to emerge at Lunksoos ferry with its pretty

clearing

sloping down to the river, and a cluster of most attractive modern log

houses,

where one may tarry for the night, or longer if his fancy pleases. Here

again

the great mountain greets the visitor, looming up, still cone-shaped,

above the

long Lunksoos ridge just across the stream. The next stage on the road

to the

Basin is a twelve-mile tramp, five of it by a very good wagon-road

across the

Lunksoos ridge to the Wissataquoik valley, at which point trampers

abandon the

tote road, and, crossing on the dam, follow a trail for seven miles

through the

forest to Ktaadn Lake. It is there, where the trail bursts out from the

stifling brush of an old burn at the outlet of the lake, that the

mountain

first appears *in its entirety. It is still some ten miles distant,

but across

the lake it spreads its nine miles of length, and rears its craggy,

slide-scarred sides, unobstructed by any intervening heights. Halfway

along

the southern shore of the lake is located another boarding-camp, — not

always open in summer, however, as it is a hunting resort, — where

a second night may be spent. For one in good tramping condition, and

not too

heavily burdened as to pack, it is easily possible to make the

eighteen miles

from Stacyville to the lake in a single day.

The route from the lake. to the Basin is a

steady

rise, for the first mile or so along an old lumber road, a pleasant

forest way,

but ere long it enters one of those ghastly burns where flies and sun

can do

their worst in a warm day. Even that four-mile desert of rock and brush

has its

compensations, with its frequent glimpses of the ever-nearing mountain

ahead,

and not far beyond lies Sandy Stream Pond with its refreshing water and

green

timber. Once more the mountain steps forth across the pond to show that

it is

still there, near enough now so that the configuration of the deep

basins in

its sides are clearly seen. Up to this point, except for the trifling

rise of

some three hundred feet to cross the Lunksoos ridge, there is no

climbing, although

the lift is steady from the Wissataquoik, seven hundred feet above the

sea, to

eleven hundred feet at Ktaadn Lake, and fifteen hundred feet at Sandy

Stream

Pond. At the pond the lumber road is left and the Appalachian Club

trail of

1916 begins, a perceptible upgrade, rising another fifteen hundred feet

in

about four miles, which lands one on the richly forested floor of the

Great

Basin itself, the chief scenic glory of the mountain.

Here, in Indian days at least, dwelt

Pamola, a harsh

and vengeful being, with head of human form surmounting the body of a

gigantic

eagle. When the winds swirl and howl there to-day, as they do even in

the midst

of summer, and especially when the rock slides start to pour from the

surrounding cliffs, as they do under the hand of the ever-undermining

elements,

it is not difficult to hear the whirring wings and the angry

mutterings as

they sounded to the terrified Abenaki huntsmen. To the white man who

is fond

of the big things in primeval nature, that great amphitheater, gouged

out of

the mountain's very head by an ancient glacier, is as satisfying in its

wildness, form, and color as many a feature of the Rockies or the

Sierra that

may be bigger.

Standing on the shore of the charming

little Chimney Pond,

that lies almost in the center of the four square miles of forested

basin

floor, and gazing up at the well-nigh vertical walls of rock that sweep

around

on the east, south, and west, pricking the clouds two thousand feet

above with

their sharp summits, serrated crests, and Gothic buttresses, one

understands

why Professor Hitchcock likened them to the peaks and ridges of the

Andes, and

why another saw here a similarity to Sierran heights and Colorado

canyons. It

is ridiculously stupendous when one considers that this is a mountain

which

lacks more than a thousand feet of Mount Washington's height, its

topmost rocks

lying somewhat less than a mile above the ocean's tide.

No finer mountain camp-ground could be

imagined than

that beside the clear, cool water of Chimney Pond, with its encircling

beds of

alpine flowers, sheltered by the dense spruce and balsam forest, and

looking

out upon that inspiring picture, a picture that is the photographer's

despair.

It defies the angle of his lens, and he cannot fail to realize how

important an

element in the composition is the rich coloring of the cliffs, a

feature that

the ordinary camera cannot compass. To be sure, it is not the high

coloring of

the Yellowstone Canyon, nor that of the Grand Canyon, nor yet quite so

intense

as that of the peaks of Glacier National Park, but those regions were

favored

above many with other materials than granite in their structure.

Geologists

tell us that Ktaadn is a granitic outburst from beneath a wide area of

sandstone and slate, its uppermost seven hundred feet being pinkish in

character, the main body gray. But those walls of so-called "gray"

rock,

that lift the eye for the first fifteen hundred feet above the pond,

are

anything but Quakerish in tone, stained, in places, with iron to a

deep

Falernian hue, and again widely encrusted with lichens that give the

olive-green tint of an ancient bronze. Ktaadn's Basin is, indeed, a

subject

worthy of any painter.

To the geologist and the botanist the

mountain is a

fascinating field, and the story of its rocks, as told by Hitchcock,.

Hamlin,

and Tarr, and that of its flora, as recorded in the files of "Rhodora,"

make interesting reading even for one who merely dabbles in those

realms. For

the geologist the great interest lies in the pronounced glacial

records that

surround it on all sides.

For the botanist its Arctic flora is the

prime

attraction, a flora unique in some respects, including many plants not

found on

the slopes of Mount Washington, among them a little saxifrage that is

unknown

elsewhere south of extreme Arctic America.

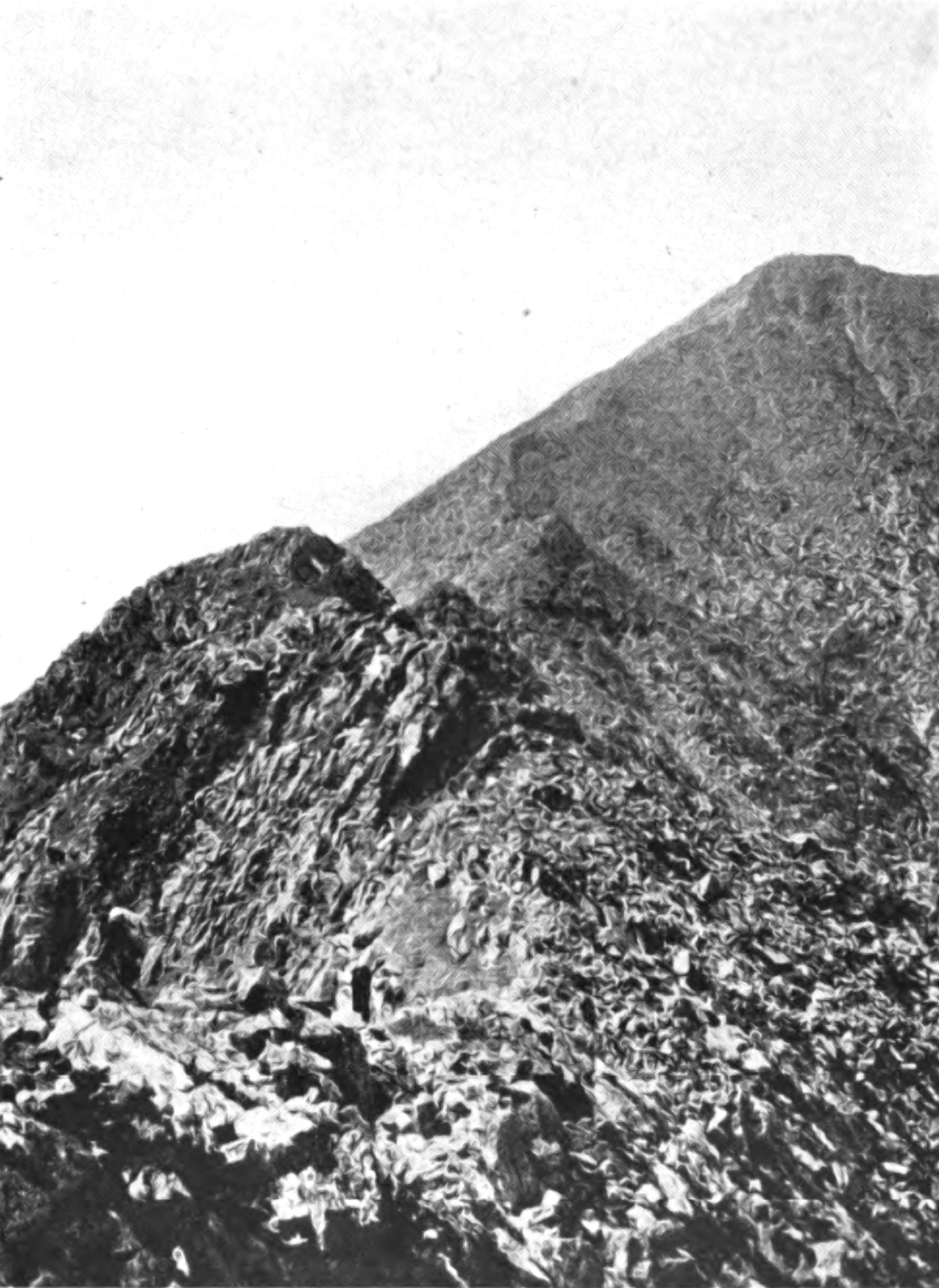

The knife-edged

crest between Pamola

Peak and the summit of Ktaadn

For the mountain-lover here is a

playground that

will keep him active and content for days together, and for his

purposes there

is no base equal to a camp in the Great Basin. Every part of the

mountain is

easily accessible thence in a day's hike. Two trails now run from Basin

to

summit, the easy and usual route being up the eight-hundred-foot rock

slide to

the Saddle which connects the North and South Mountains. There is also

the

sportier way up along the slope of Pamola Peak, and across the

knife-edged

Crest to the main summits of the South Mountain. That Pamola ascent

might not

furnish many thrills for the alpinist, but for an ordinary Eastern

mountain

tramper the. passage of the knife-edge is a safely sporty experience,

though it

is certainly not a place for giddy heads, nor for steady ones, for that

matter,

in the face of a blow. And as for stunts to satisfy the nerviest of

cliff-climbers

there are enough and to spare on the walls of the Basin itself,

including the

ascent of the Pamola Chimney, in the climbing of which one may

readily

imperil his neck, and all his limbs, at one and the same time.

Then there is the interesting Table Land,

that broad

expanse of open bench, fully a square mile in extent, spreading

westward behind

the North and South Mountains at the elevation of the Saddle, and which

in days

gone by was a favorite pasture-ground of herds of caribou. This Table

Land is

itself capable of furnishing an interesting day, with the views into

the

ravines and basins on the north and west. Nor are the almost unexplored

northerly basins too remote to be visited from a camp at Chimney Pond

in one

long day's expedition.

Naturally the view from such a mountain as

Ktaadn is

an extended and an interesting one, standing as it does relatively

alone in the

center of such a vast area of largely level wilderness. Ktaadn,

however, is by

no means a lonely mountain, as is generally supposed, for it is

associated with

quite a little family of eminences that are distinctly above the hill

class.

Traveler Mountain, a few miles to the north, is the second highest in

the

State, and Turner Mountain, its nearest neighbor on the east, and the

Sourdnahunk

Mountains that flank it on the west, are probably all of thirty-five

hundred

feet in elevation.

But Ktaadn sufficiently dominates the

landscape, and

commands a horizon that reaches from the Canadian border on the north,

around

to Mount Desert Island on the south. On a bright day it seems as if

every lake

in Maine was heliographing to you as you stand on the summit of Ktaadn.

Turner,

indeed, had the courage to count some of the lakes as he saw them on

that first

ascent in 1804, and recorded sixty-three in view on the Penobscot

watershed

alone. Fine as is the distant prospect from the mountain, Theodore

Winthrop was

right when he said that "Ktaadn's self is finer than what Ktaadn

sees," and he did not know the half of Ktaadn's beauties, for he

climbed

it from the west and in a fog. In short, Ktaadn is a worth-while

mountain about

which no one has ever bragged with sufficient extravagance to half

express its

superlativeness.

Choosing a fine day it is an easy matter

to cross

from the Great Basin to the West Branch valley, even visiting the main

South

Peak en route. Two trails lead down from the Table Land toward the West

Branch.

The more direct route follows the Abol Slide toward the south,

connecting with

the Millinocket tote road at a point about twenty miles west from the

railroad,

and close to the confluence of Abol Stream and the West Branch. The

Hunt Trail

leads across the southern end of the Table Land and down a westerly

spur

through a chaotic field of massive boulders. A mile or more below this

labyrinth is a camping-site, but if one has a boarding-camp in view

there are

two, five and six miles below, on Daisy and Kidney Ponds, in the

valley of the

Sourdnahunk Stream.

None but the most expert woodsmen will

undertake to

thread those trails across Ktaadn without a guide. Good maps of the

region do

not exist, and the trails are wholly devoid of those helpful signs,

that, in

more-frequented regions, help to keep the tenderfoot in the none too

straight

though narrow path. Blazed trees even are far from numerous, and the

blazes

are often dim, while the mazes of ancient logging roads criss-cross

that wide

country to the utter confusion of the uninitiated. Given a single week

of good

weather, and the entire passage of the mountain can easily be made

from

railroad to railroad, one of the most inspiring experiences afforded in

all New

England.

TRAIL DIRECTIONS FOR CROSSING

MOUNT KTAADN

Ascent from the East

*MILES HRS. MIN.

Sleeper train due Stacyville

about

7 A.M.

Stacyville station to western

out

skirts of farms

1.50 00

30

To Lunkasoo camp (lodging),

East Branch ferry and ford

6.50 3 30

To Dacy Dam (camp-site) 11.50 6

00

To Ktaadn Lake (lodging) — via

tote road 22 miles — by trail.

18.00

12

00

To Sandy Stream Pond (camp

site)

23.00 14 30

To Great Basin, Chimney Pond

(camp-site)

27.00

17

00

To main summit via Basin Slide 29.50

19

00

(To summit via Pamola and

Knife-Edge add one hour)

Descent on Southwest via Abol

Slide

Summit to top of slide...

1.50 00

30

To foot of slide (camp-site)...

.

3.25

1

15

To tote road (20 miles west of

Millinocket)

8.50 3

15

To West Branch, mouth of Abol

Stream

9.00

3

45

Descent on West via Hunt Trail

Summit to western edge of Table

Land.

2.00

1

00

To camp-site at foot of ridge

4.00

2 30

To tote road (25 miles west of

Millinocket, 12 hours)

5.50 3 15

To Daisy Pond (lodging)

7.00

4

00

To West Branch at mouth of

Sourdnahunk Stream

11.00

5

30

(Via Kidney Pond (lodging) add

one mile from summit

and one mile to West Branch)

* The mileage and elapsed tune are cumulative in each

of the above stages, distance and time being figured from the point

last named

in the previous line. The times here given are sufficient for leisurely

walking

with moderate-sized packs.

In descending on the western and

southwestern sides,

the railroad at Millinocket may be reached by walking east (twelve

hours) on

the tote road referred to above. Lodging halfway at Grant Brook. It is

also

possible to walk out via Moosehead Lake by following the river trail up

the

West Branch from the mouth of Sourdnahunk Stream to Ripogenus Dam, ten

miles,

walking time about five hours. From Ripogenus to steamboat at Lily Bay

landing

on Moosehead it is thirty miles via gravel road. This may be covered

by

automobile by telephoning from Ripogenus. Walkers by this route may

find lodging

at Roach Pond, twenty-two miles from Ripogenus. The usual route out

from the

Sourdnahunk valley to the railroad is by canoe, eighteen miles to

Ambejijis

Lake, and steamer thence thirteen miles to the railroad at Norcross.

|