| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Vacation Tramps in New England Highlands Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

IV

OVER VERMONT'S HIGHEST SPOTS THREE of us sat on the

westerly slope of the Sterling

Range of the Green Mountains, across which we had been toiling all

through a

richly humid July afternoon. A few years back the loggers had stripped

the

timber from many hundred acres along that mountain-side. In place of

the

shadowy spruce forest there had come up a jungle of cherry, poplar,

mountain

ash, and raspberry vines, a cover that let in the sun and shut out the

air. We

had stopped to mop for a moment, and to sample a trickle of the first

live

water we had seen for some hours. "I was thinking a while ago," said one of

my comrades, "that I never was so hot before in all the days of my

life,

and that this is a poor time of year for mountain hiking in this

latitude." "A man sweats just as hard, doesn't he,"

retorted the other man, "when he paddles up a mountain on snowshoes in

February? " About the only difference that I could see

was that

the black flies and "no-see-urns," that rose at us in swarms out of

the brush whenever we paused on that July day, are blissfully missing

in

February. Indeed, had we postponed our trip but a single month we might

have

escaped those pests which are reputed to mysteriously disappear in

August. It was three members of that outfit that

had

sauntered through the White Hills the year before who were now seeking

the wild

places of Vermont as a vacation ground. The call of the Long Trail of

the Green

Mountain Club had come to us. In the first place, we were a bit ashamed

at

realizing how little we knew of the physical geography of the Green

Mountain

State. And yet were we wholly to blame? Fifty years ago Vermont people

conceived the idea that their mountains were destined to win public

appreciation as summer resorts, and hotels were built on a few of the

principal

summits. Of these but one is still entertaining guests. The others

failed to

receive the anticipated appreciation and long since disappeared by

fire, porcupines,

or decay. Within the past few years the tramping cult having been

espoused by

the Vermonters themselves, the Green Mountain Club has energetically

begun the

systematic development of the walking possibilities, and the region is

surely

destined now to become popular with the hiker. They have the hills, and

the

State has been doing its part toward the protection and restoration of

the

forests. The trails are stretching out north and south along the main

ranges

year by year. Steadily these are being improved, and as the traffic

increases

so will the incidental facilities, such as lodging-camps, multiply. For our week afield we had chosen that

section of the

Long Trail that tops the highest peaks and ridges of the north central

portion

of the range, linking Sterling Mountain with Mount Mansfield, master of

them

all, and so south to Bolton's wooded crown and over the ridges of

Camel's Hump.

For the same reasons that attracted us, this section of the trail seems

likely

to win great popularity, leading as it does to two of the highest and

best-known summits, and past the doors of hospitable camps and hotels

that are

happily located a fair day's march apart. Should any be tempted to follow in our

footsteps, let

him not suppose that this is a stroll on graded paths where ankle-ties

may be

worn in comfort. There are stretches, in fact, that are rough enough to

please

the fancy of the toughest woodsman, and yet the way is sufficiently

clear for

any one familiar with mountain trails to follow safely. It was

pathetic to

note the track of a woman's foot in a muddy bit of trail, the pointed

toe,

narrow shank, and peg heel, all spelling plainly the fatigue and

general

discomfort that must have been the wearer's lot for days after that

experience.

Let the novice, whatever the gender, take advice from the experienced

before

setting forth, and sanely following the same go merrily tripping, where

otherwise it might be a woeful hobble. To do full justice to the course of the

trail as it

lies from Johnson village, just north of Sterling Mountain, over Mount

Mansfield to Camel's Hump, requires at least four full days of

regulation

summer daylight length. For the more leisurely yet another day, or even

more,

would be added without waste of time. It is not difficult to surmise

into which

class our party naturally fell. In truth, we would cheerfully have

exchanged

our first day's experience for something much less energetic. Fifteen

miles on

a long summer's day is not an inordinately extended march in the

mountains for

any fairly seasoned walker. It is confessed that we were

temperamentally

averse to hiking, at least in so far as that word is synonymous with

hustling,

and greatly given to viewing the landscape o'er in leisurely fashion

from every

coign of vantage. To feel the pinch of time along a beautiful forest

trail, or

on a sightly ridge path, is as annoying as poverty in the financial

sense.

When one has journeyed a hundred miles or more to visit new scenes, he

feels

that he wants his money's worth. It is the firm conviction of

old-timers that

"hustle "is a word that should be left in town with store clothes

when a walking trip is on. That fifteen miles or so across the

Sterling Range

from Johnson village, on the St. Johnsbury & Lake Champlain

Railroad, to

the depths of Smuggler's Notch, is a stretch to be approached with

respectful

consideration. By one mountaineer the distance was given to us as "at

least fifteen miles." By yet another it was given with greater

exactness,

so we later thought, even if with less mathematical precision, when he

said it

was farther than he wanted to foot it on a hot day. With its ups and

downs of

contour, and its overs and unders of windfalls (the latter a temporary

handicap not likely to be present in every season), enough foot pounds

of

effort were required to have taken us up and across the Presidential

Peaks of

the White Mountains. For one equipped with his own bed and board, a

cabin, readily

found on a side trail, is available between Morse Mountain and the

Madonna, ten

miles or less south of Johnson. On a less perspiry day, and with a

cleared

trail, the need for such a halting-place would not be felt. A mountain tarn is ever a pleasing

feature, and the

three-lobed Sterling Pond, that mirrors the forest at the western base

of the

Madonna's cone, is a delightful spot to tarry by before making the

long

downward plunge into Smuggler's Notch. Two routes lead thither from the

westerly end of the pond, both attractive in their way. The shorter

leads south

along a timbered ridge to descend over the old logging roads down the

steep

southern cut-over face of the mountain, with views across the notch to

Mount

Mansfield. The longer way follows down through the forest to the

northern end

of the notch, near the height of land, where it joins the highroad. In

distance

the latter is longer, but it has its compensations, and it includes the

passage

of the beautiful notch as a part of the trip. Worth while as it is the Sterling

Mountain link is

not an essential feature of the Mount Mansfield-Camel's Hump jaunt,

except for

those who tramp purely for tramping's sake. The link across Bolton

Mountain,

between Mount Mansfield and Camel's Hump, may similarly be eliminated;

at least

until the view from Bolton Mountain, which ought to be impressive, is

made

available by the erection of a tower on the wooded summit. One of the

advantages of the Long Trail is in the ease with which it may be broken

in upon

or left on any day. So Barnes' Camp, the tramper's haven at the

southerly end

of Smuggler's Notch, is readily found from the railroad at Waterbury

via the

trolley line to Stowe. A night at the camp may profitably be followed

by a

forenoon's exploration of the notch, which in two miles has more to

show in

natural curiosities than many another more celebrated mountain cleft.

Were it

not for the great spring that furnishes an outlet for Sterling Pond,

fifteen

hundred feet or more above, or for the house-size fragments of Mount

Mansfield's

cliffs that have come down from time to time to choke the gorge, or for

the

great caves and early summer snowbanks in the eastern flank of the big

mountain, the notch would still be an attraction because of the

towering rock

walls rising sheer a full thousand feet on either hand. Smuggler's Notch enjoys the geographical

distinction

of being the only pass through the main Green Mountain Range that has a

north-and-south trend, all other passes leading east and west.

Appropriate to

its name there is a tradition of somewhat elusive origin, and

apparently not

widely known, that lends a flavor of frontier picturesqueness to the

place. In

ye olden time, somewhat more than a hundred years ago, or more

explicitly just

prior to the war with Great Britain in 1812, Congress placed a ban on

all

commercial dealings between the States and Canada. As a result every

"Stealthy

Steve "along the border saw his chance to turn a perfectly sound though

dishonest dollar in the crafty trade of smuggling. In this the Vermont

border

played an active part, much of the plunder being transported across

Champlain,

where brushes with the customs officers were not infrequent. It was one

of

these illicit freighters, so the story goes, who, being hard pressed by

the

revenue men, fled to this mountain fastness with his family. Some there

are who

say that a mysterious man, who long ago lived in the southern end of

the notch,

was probably the escaped and remorseful smuggler, while others point

to a

poem, written in the early fifties by a resident of Stowe, in which the

smuggler is finally rescued from his exile by a son, once a member of

the

band, but who had become prosperous in a supposedly reformed career in

the

great West. Be all this as it may, one can see the cave to-day wherein

this

smuggler, and perchance many another too, may have hidden. Many years ago a small hotel was built

near the great

spring, but although its day has passed, the spring remains as one of

the chief

attractions of the notch. Issuing from the foot of the cliffs of

Sterling

Mountain, it wells up at the estimated rate of between one hundred and

two

hundred gallons to the minute, and maintains a constant temperature,

winter

and summer, of approximately fifty degrees Fahrenheit. Geologists have

apparently

arrived at the conclusion that this water works its way down through

the rock

fissures from Sterling Pond. Of the great rocks that have fallen into

the notch

from the Mansfield side, two are of especial note on account of their

truly

enormous size, and because an interval of exactly one hundred years

elapsed

between their falls. Barton's Rock, so-called because it fell on the

day when a

new son of the hills, Barton Ingraham, was born in 1811, is surpassed

in size

by the King Rock, estimated to weigh not far from five thousand tons,

which

was torn from the cliffs a thousand feet above in 1911. The notch is

sure to

be recognized as one of the great scenic features of New England. It

but awaits

the completion of the State highway through to the valley of the

Lamoille River

to bring it into connection with an appreciative public. From Barnes' Camp it is an easy

afternoon's climb of

two thousand feet, or a trifle more, along just rising two miles of

most

enchanting forest trail, to the little hotel that stands midway on the

four-miles-long ridge of Mount Mansfield, the true-enough high spot of

Vermont.

This hotel enjoys the distinction of being the sole survivor of the

three Green

Mountain crest retreats, built at about the same period, or just before

the

Civil War, the others having been located on Camel's Hump and on

Killington

Peak. This one on Mount Mansfield, the oldest of the three, dates from

1857,

and still breasts the storms as gallantly as of yore. A night there is

not

imperative if one will devote a long full day to crossing the mountain

from

Smuggler's Notch to Nebraska Notch, which is the next lodging-station

along the

trail. No leisurely mountain lover would willingly hasten here,

however, for

the big mountain in its rocks and flora holds much to interest even the

amateur

in geological and botanical science, and there are two peaks, a mile

and a half

apart, to explore for a comparison of views, not to speak of caverns

whose

galleries are said to ramify for fully two hundred feet within the

summit

rocks.  Mount Mansfield, with Smuggler's Notch and the Sterling Range to the east. To the geologist Mount Mansfield tells a

wonderful

tale of how the vast glacial flood of eons past came dashing upon it

from the

north, engulfing its topmost crags, even grinding them away in part.

Not only

do the summit ledges, rounded by the overriding ice, still bear the

grooves and

scratches scoured into them by the grit that the glacier dragged

along, but

here and there are still perched fragments of the selfsame grit, huge

bits

plucked from the mountain's own flanks, some, indeed, brought from

afar, and

left stranded there by the melting mantle. In the woods beside the

mountain

carriage road, not far below the hotel (elevation 3250), lies a

five-foot

boulder of labradorite that commands the attention of every

geologically

inclined visitor. This bit of Vermont landscape was probably born

somewhere

to the northward of Montreal, more than one hundred miles away, since

it is

there that the nearest parent ledges of that form of rock are native.

Its

deportation from Canada across the border to the Green Mountain State

was

decreed and carried out by the irresistible forces of the arctic

invader of

old. It is small wonder that the University of

Vermont men

take so great an interest in the mountains of the State, and in their

development

as an attraction for tourists, since the title to this, the highest

summit, is

in large part vested in their institution. And the State itself is

showing a

jealous regard for the forests of its greatest mountain, and has

already

acquired large tracts, exceeding in all five thousand acres, reaching

from the

summit far down the slopes on the east and south, a beginning for a

reservation

that it is to be hoped will eventually include the mountain as a whole.

Six and a quarter miles of pleasant forest

jogging

lies between the Nose, the central and second highest summit on the

Mansfield

ridge, and Lake Mansfield, at the eastern entrance to Nebraska Notch,

where

the most genuine and generous hospitality is extended to wanderers over

the

Long Trail by the members of the Trout Club. It has already been intimated that the

eleven and a

quarter miles across Bolton Mountain, from Lake Mansfield to the

northern

flanks of Camel's Hump in the Winooski valley, may be treated

censoriously,

or, in other words, deleted, until the summit view, now shut in by the

forest,

is opened up by vista-cutting, or by the erection of a tripod tower.

With its

dashing trout-brook it has its attractions none the less, and the trail

is

clearly marked and easily followed. The twenty miles of pretty country

road

that lie between the Trout Club and the ford at Bolton village, where

begins

the ascent of Camel's Hump, are made agreeably possible to-day, even

after a

leisurely breakfast, by virtue of the ever-present "flivver "and its

modest rate of hire. By the Long Trail proper to the summit of

Camel's

Hump it is four and a half miles of steady uphill through the woods,

and across

a bit of brush-grown burn, from the Bolton ford. As an alternative

there is the

slightly longer drive from the Trout Club through Waterbury, to cross

the

Winooski River by the only bridge in several miles, to approach the

mountain

from the North Duxbury side by the Callahan Trail. By this route three

miles of

relatively easy upgrade makes the summit, with its little group of

three

galvanized-iron huts, located in a cozy glade under the northern

shoulder of

the peak, where for seventeen years stood the Green Mountain House,

until fire

removed it in 1877. Here, too, are bed and board of the usual

unpretending

mountain sort, set out by the hospitality of the Camel's Hump Club of

Waterbury. Whoever it was who fastened upon this

mountain the

name of "Camel's Hump" would be without honor with many in Vermont

to-day.

Descriptive it may be as the mountain's peaked top is seen from some

points of

view, but no one who has gazed that way from Burlington on the west, or

looked

up at its summit from the Duxbury valley at its eastern foot, could

fail to

feel the greater truthfulness of the name that tradition says was

bestowed upon

it in the early years of the seventeenth century by the chaplain of

Champlain's

expedition "Le Lion

Couchant." As "Le Lion Couchant" it was known in 1851

to Frederika Bremer, a Swedish novelist, who thus named it in her

"Impressions

of America," terming it "a magnificent giant form." The

appropriateness of the original name must likewise have impressed

William Dean

Howells at the time of his writing the story of "The Landlord of the

Lion's

Head." He there described the mountain's outline as having "the form

of a sleeping lion, . . . the mighty head resting, with the tossed

mane, upon

the vast paws stretched before it." And so if Vermonters have their way

the mountain's strength and majesty, the memory of the French

discoverers, and

the eternal fitness of things, will all be given recognition in a

rechristening of "The Couching Lion." It will be well to bear this in

mind when following the Long Trail where the arrow-signs that point the

way

frequently bear the legend of so many miles to Couching Lion. Although four hundred feet lower than

Mount

Mansfield, this mountain, standing out by itself with naked cone,

commands a

view that is more extended than that from its big sister to the north.

Its

summit is distinctly a place where one would loiter indefinitely in

fair

weather, and we were favored by a lifting of the haze for as fair a

summer

afternoon's view as one could desire, a view that ranged north to the

Quebec

border, east to Camel's Rump in Maine, and to the White Mountains,

south along

the Green Mountain Ranges, with their wide, cultivated troughs

between, and

west over Lake Champlain to the tumbling masses of the Adirondacks: an

afternoon of sunshine and floating cloud-forms, succeeded by a

spectacular

sunset, and the golden splendors of a full moon. FIVE DAYS ON VERMONT'S HIGH SPOTS First Day

MILES

HRS. MIN. Johnson Station (H. & M. R.R.) to

Whiteface summit

5.50

3 30 To Morse Mountain and Madonna summit (shelter campen route)

9.75

6 30 To Sterling Pond.

11.75 7 30 To Smuggler's Notch (Barnes'

Camp)

15.00 10 00 Second Day

MILES

HRS. MIN Barnes' Camp to Mansfield Nose . via Running Water Trail . . .

2.33

2 00 To the Chin, main summit, and return to hotel at Nose

5.33

5

00 Third Day

Nose to Lake Mansfield Trout

Club

6.25

5

00 Fourth Day

Lake Mansfield to Bolton Mountain summit.

3.50

4

00 To Bolton village

11.25 9 00 Fifth Day

Bolton to Couching Lion summit 4.50

5

00 To Callahan Farm at North

Duxbury base

7.50

7

00 To Central Vermont Railroad at North Duxbury via highway

11.10 8

30 * The mileage and elapsed time are

cumulative for

each day, distance and time being figured from point last named in

previous

line. The times here given are sufficient for leisurely walking. The

trail from

Johnson to Smuggler's Notch is unsurveyed and distances given are

therefore

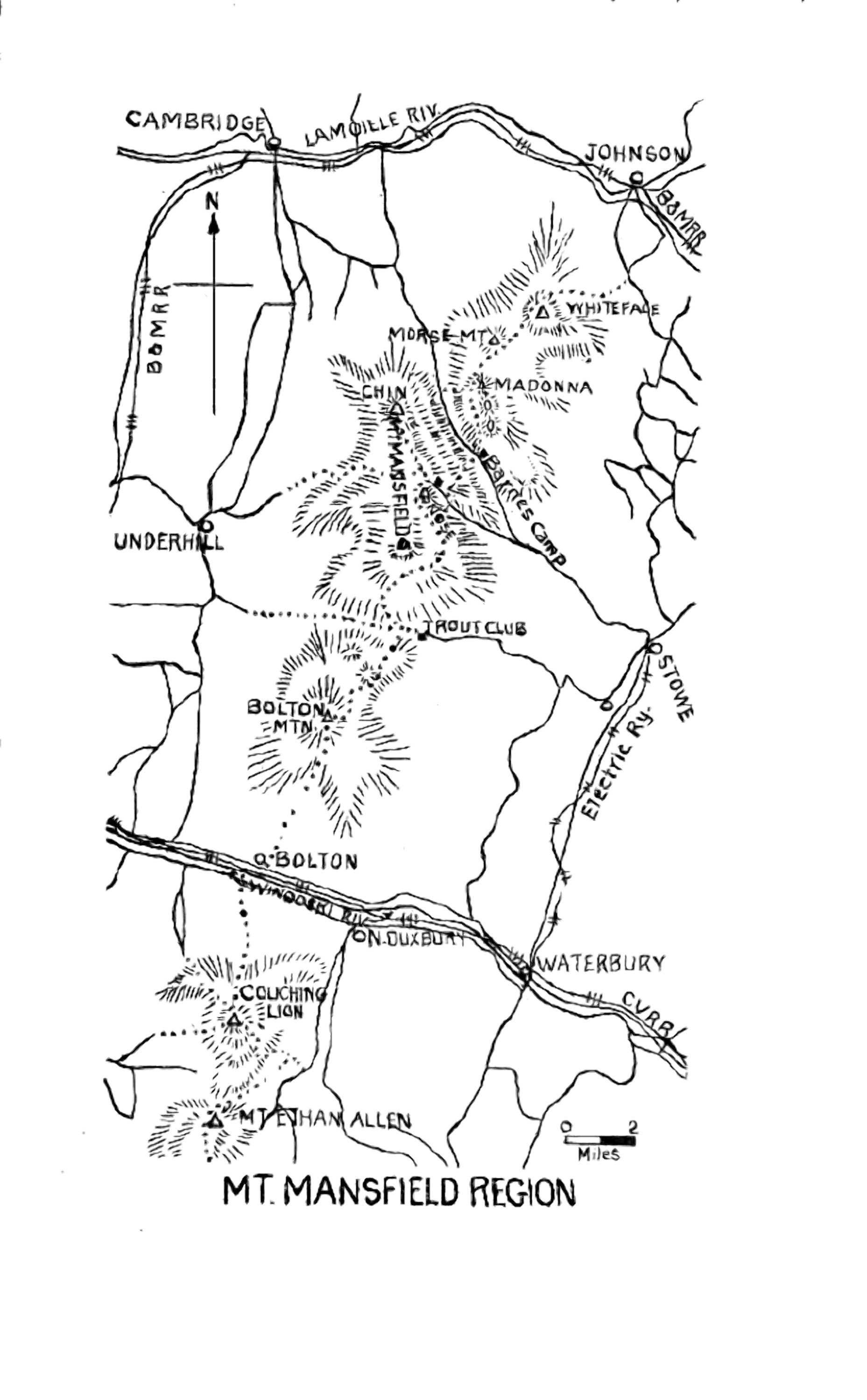

approximate. MAP: Trail survey from Smuggler's Notch to

Couching

Lion, by Herbert Wheaton Congdon, and published by Green Mountain Club,

Burlington, Vt. |