| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

| I THE TRAMPER'S PARADISE IF Thoreau had

lived in this day and generation, it

is safe to say that he never would have written as he did, half a

century or

more ago, that he had met but one or two persons in his life who had "a

genius," as he termed it, for walking. According to his notion "it

requires a direct dispensation from Heaven to become a walker." There

is a

thought that ought to enable any dusty hiker to hold up his head and

look

haughty whenever a big touring car goes tearing past him on the road.

It would

almost seem to bring the Sunday tramper within the pale, too. The fact

of the

matter is that Thoreau sowed a good many fertile thoughts of this

nature that

fell upon fallow ground. This one has been slowly germinating and

steadily

reproducing its kind in all these years, until to-day even the Concord

hermit

would doubtless be pleased to bestow an approving smile upon the

mountaineering

and walking clubs, with memberships running into the thousands, that

are found

from coast to coast. Even the Federal Government officers who have

charge of

our National Parks and National Forests find that the most appreciative

visitors to those domains are not the automobile-borne tourists, but

the

pedestrians. Thoreau's native New England is more and

more coming

to be regarded as one of the tramper's choicest fields. Where else in

the

country can there be found so many miles of attractive trails adapted

to his

purposes, or leading through a more varied landscape? True, that

scenery may

not be of the vast and awe-inspiring nature of the Grand Canyon, or the

Yosemite, or of Mount Rainier, or of many of the other of our great

Western

playgrounds, but when attractive landscapes were being apportioned on

this

continent New England was not by any means ignored. Although none of

the

greatest of the monumental features were allotted here, the region did

fall heir

to much that was beautiful and inspiring, even if of a less

spectacular

nature. It would be difficult to find, the country over, such variety

of ocean

shore, of lake and river, of verdurous rolling upland, of upstanding

mountain

ranges. Thoreau looked forward to a day when

"possibly .

. . fences shall be multiplied, and man-traps and other engines

invented to

confine men to the public road, and walking over the surface of God's

earth

shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman's grounds."

He

gloried in the fact that in his day "the landscape is not owned, and

the

walker enjoys comparative freedom." To a considerable extent his

prophecy

has been fulfilled, but may we not believe that his "possibly"

denoted that he foresaw the likelihood that Yankee democracy would one

day

find a remedy? Already the public importance of New England's scenery

has been

recognized — in

spots — by

her people, and reservations have been created at public expense for

the purpose

of guarding unique features in the interest of the community. The

native beauty

of New England's landscape, however, is not confined to spots, and its

attractiveness will become more and more apparent as the improved roads

stretch

out, opening regions little visited to-day. Even our highest courts have admitted that

scenic

beauty has a recognizable value which must be protected in the public

interest.

It was the Supreme Court of Massachusetts that decided that a

Berkshire

trout-brook is of value to the public because of the rest, recreation,

and

enjoyment which it is capable of affording to those who visit it, and

on that

ground has upheld the constitutionality of a law which prohibits the

discharge

of polluting material into such streams. A similar attitude was taken

by a

United States district judge in Colorado, who enjoined a power company

from

destroying a canyon waterfall which forms the chief scenic feature on

the

outskirts of the town of Cascade. Such decisions are calculated to give

pause to those

who have contended that only the commercial development of our natural

resources

could be considered under the head of conservation in the interest of

the

public. The country has been coming to this gradually during the past

fifty

years, and one of the earliest public acts recognizing the intrinsic

value of

scenery as a public asset was the creation of the Yellowstone National

Park by

Congressional enactment in 1872. The principle was also recognized by

the

historic White House Conference of Governors, and later it was

expressed, more

definitely even, in the official declaration of the National

Conservation

Commission, that "public lands more valuable for conserving . . .

natural

beauties or wonders than for agriculture should be held for the use of

the

people." Switzerland long ago saw the wisdom of

capitalizing

her scenery. The millions of dollars that have been spent there yearly

by those

who sought refreshment amidst those scenes, attest to the business

success of

the idea. Canada, too, was prompt to appreciate this point, her

Government

cooperating in the opening-up of her superb mountain regions, so that

their

charms should be accessible to the traveler. But it is not every one who can travel

afar to see

the glories of the Alps, of the Canadian Rockies, or of our own superb

National

Parks and Monuments. The beauties of the simple Berkshire trout-stream

are

important as conservators of the health and happiness of scores of the

present

generation, and of thousands of those who are to follow) and who shall

say that

these beauties are less sublime or less potent in inspiration and

life-giving

qualities than the much-advertised, and perhaps more spectacular,

scenes of

far-off states and foreign lands? Under the economic arrangements of the

present it is

impossible to put a park fence around all creation, no matter how

lovely it may

be. There is a thought abroad in New England, though, that such

reservations as

we have might in a sense be linked together to form a sort of system

that will

extend even from Long Island Sound to the Quebec border, and from the

Adirondacks to New Brunswick. In this the aim is to devise means for a

more

complete opening-up of the scenery, particularly of the hill and

mountain country,

through the development of a system of trunk trails, to be built and

maintained

as a coordinated enterprise, and linking up the great National Forest

in the

White Mountains, the State wild parks, State forests, and certain

quasi-public

forests and reservations maintained by educational and other

institutions. Not

all of these public properties are located among the highlands to be

sure, but

many of the largest areas are directly tributary to the plan for a

comprehensive system of through trails following the main mountain

ridges, and

crossing the wilder sections. It is along the ridges in particular

where, in

all probability, many more publicly owned forests will be established

as the

years go on, for it is essentially a feature of any plan to conserve

our stream

resources that their forested headwaters should be given ample

protection

against denudation. As protectors of our streams, and as

sources of

future timber supplies, these public forests are of undoubted

importance. That

they are also destined to play an increasingly large part in the

recreational

life of the community there can be no question. Who will challenge the

belief

that this fostering of the public health and morals is of 4, less

economic

consequence than those more material phases first alluded to? Nor can

there be

any danger but that bringing the public into closer contact with its

own forest

property in this way will arouse a more intelligent interest in

forestry in all

its branches. Forest authorities everywhere seem to think that this is

so, and

they quite universally regard the recreational use of these properties

as one

of their most important functions. Naturally it is our high country that

attracts the

summer tramper, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire, because of

the

facilities afforded to all comers in the shape of trails, rest-houses,

and

camps, supplied largely through the public-spirited activity of the

Appalachian

Mountain Club, and various local improvement organizations, not to

mention

those handy adjuncts called hotels, which everywhere abound, has for a

long

time been the best-known and favorite rambling-ground. To Thoreau the

"mountain

houses," as he termed the local resort hotels of his day, were

anathema,

as from his point of view in 1858 they "render traveling thereabouts

unpleasant." Doubtless to him such conveniences detracted from the

primitive wildness that he craved in undiluted doses. Quite recently

the Green

Mountains of Vermont have come to bid for attention as a promising

tramping

section. When it comes to be generally known that there are

possibilities in

that line there, another splendid field will be afforded the

pedestrian. The

Long Trail. along the sky-line of the Green Mountain chain from the

Massachusetts line to the Canadian border, as laid out by the Green

Mountain

Club, will offer three hundred miles and more of highland ways, nearly

half of

which are already open. The rest will come in time, making a walking

route that

will in all respects be as enjoyable as the long-celebrated path system

of

Germany's Black Forest. Everywhere throughout New England mountain

hamlets

are found local clubs devoted to the development of their surrounding

heights

as trampers' havens. It would not be surprising if another decade saw

the

realization of the hope for the New England system of through trails.

While

there will be few whose zeal, even though Heaven-inspired, as Thoreau

said,

will lead them to attempt the complete round, the system will not

supply more

than enough trail to accommodate the steadily increasing army of those

who

delight in the toting of the pack-bag. And so the spirit of Thoreau

literally

goes marching on.

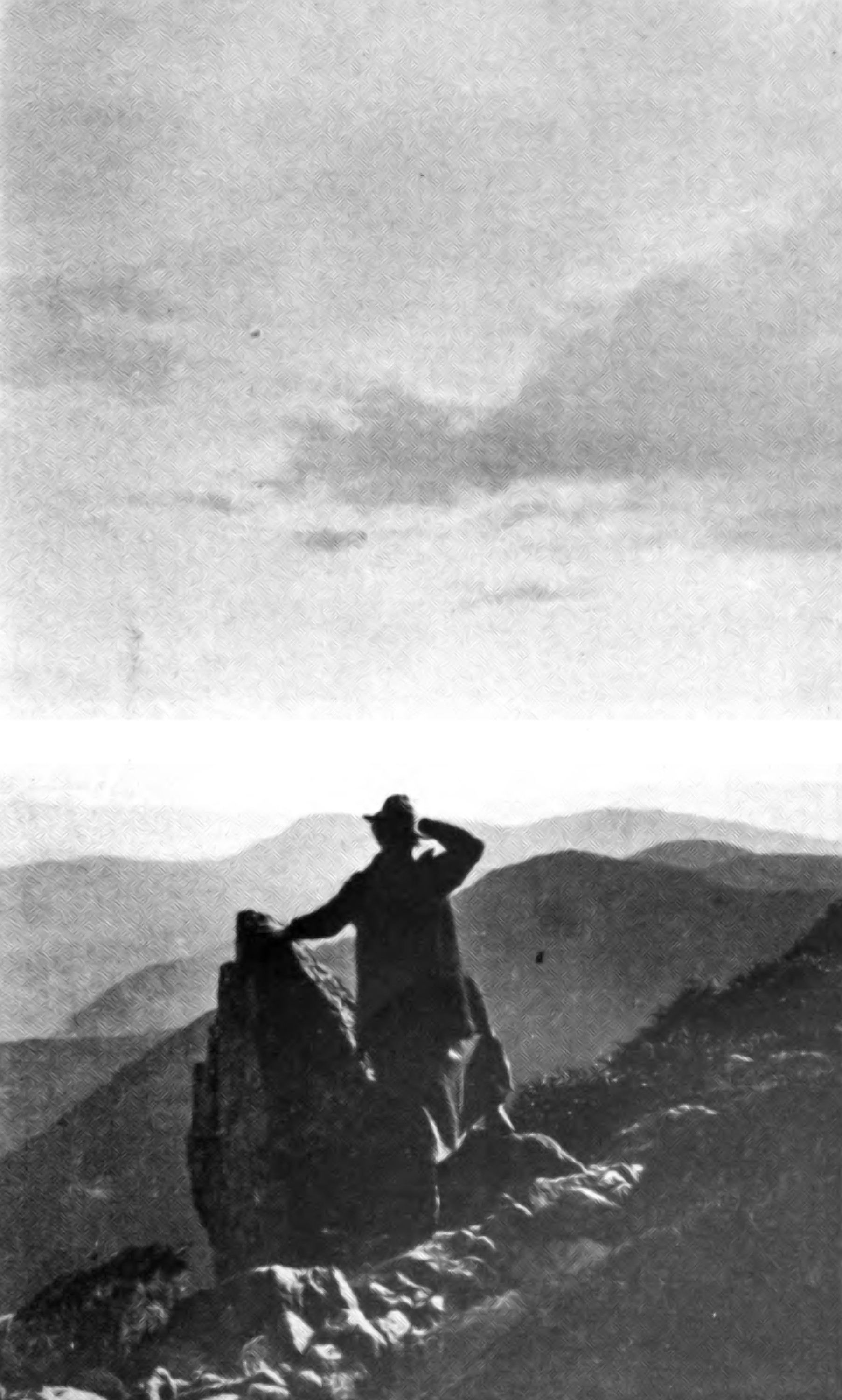

A sunset from the crags of Mt. Monroe |