| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER XVIII. DISCOVERIES AT ABOU

SIMBEL. WE came

back to find a fleet of dahabeeyahs ranged along the shore at

Abou Simbel, and no less than three sketching tents in occupation of

the

ground. One of these, which happened to be pitched on the precise spot

vacated

by our painter, was courteously shifted to make way for the original

tenant;

and in the course of a couple of hours, we were all as much at home as

if we

had not been away for half-a-day. Here,

meanwhile, was our old acquaintance –

the Fostât, with her party of

gentlemen; yonder the Zenobia, all ladies; the little Alice, with Sir

J. C----- and

Mr. W----- on board; the Sirena flying the stars and stripes; the

Mansoorah, bound

presently for the Fayûm. To these were next day added the Ebers,

with a couple

of German savants; and the Bagstones, welcome back from Wady Halfeh. What with arrivals and departures, exchange of visits, exhibitions of sketches, and sociabilities of various kinds, we had now quite a gay time. The Philæ gave a dinner-party and fantasia under the very noses of the colossi, and every evening there was drumming and howling enough among the assembled crews to raise the ghosts of Rameses and all his Queens. This was pleasant enough while it lasted; but when the strangers dropped off one by one, and at the end of three days we were once more alone, I think we were not sorry. The place was, somehow, too solemn for “Singing, laughing,

ogling, and all that.”

It was by

comparing our watches with those of the travellers whom we met

at Abou Simbel, that we now found out how hopelessly our timekeepers

and theirs

had gone astray. We had

been altering ours continually ever since leaving Cairo; but the

sun was as continually putting them wrong again, so that we had lost

all count

of the true time. The first words with which we now greeted a newcomer

were –

“Do you know what o’clock it is?” To which the

stranger as invariably replied

that it was the very question he was himself about to ask. The

confusion became

at last so great that, finding that we had about eleven hours of day to

thirteen of night, we decided to establish an arbitrary canon; so we

called it

seven when the sun rose, and six when it set, which answered every

purpose. It was

between two and four o’clock, according to this time of ours,

that the Southern Cross was now visible every morning. It is

undoubtedly best

seen at Abou Simbel. The river is here very wide, and just where the

constellation rises there is an opening in the mountains on the eastern

bank,

so that these four fine stars, though still low in the heavens, are

seen in a

free space of sky. If they make, even so, a less magnificent appearance

than

one has been led to expect, it is probably because we see them from too

low a

point of view. To say that a constellation is foreshortened sounds

absurd; yet

that is just what is the matter with the Southern Cross at Abou Simbel.

Viewed

at an angle of about 30°, it necessarily looks distort and dim. If

seen burning

in the zenith, it would no doubt come up to the level of its

reputation. It was now

the fifth day after our return from Wady Halfeh, when an

event occurred that roused us to an unwonted pitch of excitement, and

kept us

at high pressure throughout the rest of our time. The

day

was Sunday; the date February 16th, 1874; the time, according to

Philæ reckoning, about eleven A.M., when the painter, enjoying

his seventh

day’s holiday after his own fashion, went strolling about among

the rocks. He

happened to turn his steps southwards, and passing the front of the

great temple, climbed to the top of a little shapeless mound of fallen

cliff,

and

sand, and crude-brick wall, just against the corner where the mountain

slopes

down to the river. Immediately round this corner, looking almost due

south, and

approachable by only a narrow ledge of rock, are two votive tablets

sculptured

and painted, both of the thirty-eighth year of Rameses II. We had seen

these

from the river as we came back from Wady Halfeh, and had remarked how

fine the

view must be from that point. Beyond the fact that they are coloured,

and that

the colour upon them is still bright, there is nothing remarkable about

these

inscriptions. There are many such at Abou Simbel. Our painter did not,

therefore, come here to examine the tablets; he was attracted solely by

the

view. Turning

back presently, his attention was arrested by some much

mutilated sculptures on the face of the rock, a few yards nearer the

south

buttress of the temple. He had seen these sculptures before – so,

indeed, had

I, when wandering about that first day in search of a point of view

– without

especially remarking them. The relief was low, the execution slight;

and the

surface so broken away that only a few confused outlines remained. The thing

that now caught the painter’s eye, however, was a long crack

running transversely down the face of the rock. It was such a crack as

might

have been caused, one would say, by blasting. He stooped

– cleared the sand away a little with his hand – observed

that the crack widened – poked in the point of his stick; and

found that it

penetrated to a depth of two or three feet. Even then, it seemed to him

to

stop, not because it encountered any obstacle, but because the crack

was not

wide enough to admit the thick end of the stick. This

surprised him. No mere fault in the natural rock, he thought, would

go so deep. He scooped away a little more sand; and still the cleft

widened. He

introduced the stick a second time. It was a long palm-stick like an

alpenstock, and it measured about five feet in length. When he probed

the cleft

with it this second time, it went in freely up to where he held it in

his hand

– that is to say, to a depth of quite four feet. Convinced

now that there was some hidden cavity in the rock, he

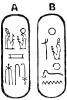

carefully examined the surface. There were yet visible a few

hieroglyphic

characters and part of two cartouches, as well as some battered

outlines of

what had once been figures. The heads of these figures were gone (the

face of

the rock, with whatever may have been sculptured upon it, having come

away

bodily at this point), while from the waist downwards they were hidden

under

the sand. Only some hands and arms, in short, could be made out. They were

the hands and arms, apparently, of four figures; two in the

centre of the composition, and two at the extremities. The two centre

ones,

which seemed to be back to back, probably represented gods; the outer

ones,

worshippers. All at

once, it flashed upon the painter that he had seen this kind of

group many a time before – and

generally over

a doorway. Feeling

sure now that he was on the brink of a discovery, he came back;

fetched away Salame and Mehemet Ali; and without saying a syllable to

any one,

set to work with these two to scrape away the sand at the spot where

the crack

widened. Meanwhile,

the luncheon bell having rung thrice, we concluded that the painter had rambled off somewhere into the desert; and so sat down

without him.

Towards the close of the meal, however, came a pencilled note, the

contents of

which ran as follows: “Pray

come immediately – I have found the entrance to a tomb. Please

send some sandwiches – A. M’C.”

To follow

the messenger at once to the scene of action was the general

impulse. In less than ten minutes we were there, asking breathless

questions,

peeping in through the fast-widening aperture, and helping to clear

away the

sand. All that

Sunday afternoon, heedless of possible sunstroke, unconscious

of fatigue, we toiled upon our hands and knees, as for bare life, under

the

burning sun. We had all the crew up, working like tigers. Every one

helped;

even the dragoman and the two maids. More than once, when we paused for

a

moment’s breathing space, we said to each other: “If those

at home could see

us, what would they say!” And now,

more than ever, we felt the need of implements. With a spade or

two and a wheelbarrow, we could have done wonders; but with only one

small

fire-shovel, a birch broom, a couple of charcoal baskets, and about

twenty

pairs of hands, we were poor indeed. What was wanted in means, however,

was

made up in method. Some scraped away the sand; some gathered it into

baskets;

some carried the baskets to the edge of the cliff, and emptied them

into the

river. The idle man distinguished himself by scooping out a channel

where the

slope was steepest; which greatly facilitated the work. Emptied down

this shoot

and kept continually going, the sand poured off in a steady stream like

water. Meanwhile

the opening grew rapidly larger. When we first came up – that

is, when the painter and the two sailors had been working on it for

about an

hour – we found a hole scarcely as large as one’s hand,

through which it was

just possible to catch a dim glimpse of painted walls within. By

sunset, the

top of the doorway was laid bare, and where the crack ended in a large

triangular fracture, there was an aperture about a foot and a half

square, into

which Mehemet Ali was the first to squeeze his way. We passed him in a

candle

and a box of matches; but he came out again directly, saying that it

was a most

beautiful Birbeh, and

quite light

within. The writer

wriggled in next. She found herself looking down from the top

of a sandslope into a small square chamber. This sand-drift, which here

rose to

within a foot and a half of the top of the doorway, was heaped to the

ceiling

in the corner behind the door, and thence sloped steeply down,

completely

covering the floor. There was light enough to see every detail

distinctly – the

painted frieze running round just under the ceiling; the bas-relief

sculptures

on the walls, gorgeous with unfaded colour; the smooth sand, pitted

near the

top, where Mehemet Ali had trodden, but undisturbed elsewhere by human

foot;

the great gap in the middle of the ceiling, where the rock had given

way; the

fallen fragments on the floor, now almost buried in sand. Satisfied

that the place was absolutely fresh and untouched, the writer

crawled out, and the others, one by one, crawled in. When each had seen

it in

turn, the opening was barricaded for the night; the sailors being

forbidden to

enter it, lest they should injure the decorations. That

evening was held a solemn council, whereat it was decided that

Talhamy and Reïs Hassan should go to-morrow to the nearest

village, there to

engage the services of fifty able-bodied natives. With such help, we

calculated

that the place might easily be cleared in two days. If it was a tomb,

we hoped

to discover the entrance to the mummy pit below; if but a small chapel,

or speos, like those at Ibrim, we should at least have the satisfaction of

seeing

all that it contained in the way of sculptures and inscriptions. This was

accordingly done; but we worked again next morning just the

same, til mid-day. Our native contingent, numbering about forty men,

then made

their appearance in a rickety old boat, the bottom of which was half

full of

water. They had

been told to bring implements; and they did bring such as they

had – two broken oars to dig with, some baskets, and a number of

little slips

of planking which, being tied between two pieces of rope and drawn

along the

surface, acted as scrapers, and were useful as far as they went.

Squatting in

double file from the entrance of the speos to the edge of the cliff,

and to the

burden of a rude chant propelling these improvised scrapers, the men

began by

clearing a path to the doorway. This gave them work enough for the

afternoon.

At sunset, when they dispersed, the path was scooped out to a depth of

four

feet, like a miniature railway cutting betweeen embankments of sand. Next

morning came the sheik in person, with his two sons and a

following of a hundred men. This was so many more than we had bargained

for,

that we at once foresaw a scheme to extort money. The sheik, however,

proved

to be that same Rashwan Ebn Hassan el Kashef, by whom the happy couple

had been

so hospitably entertained about a fortnight before; we therefore

received him

with honour, invited him to luncheon, and, hoping to get the work done,

quickly

set the men on in gangs under the superintendence of Reïs Hassan

and the head

sailor. By noon,

the door was cleared down to the threshold, and the whole south

and west walls were laid bare to the floor. We now

found that the débris which blocked the north wall and the

centre

of the floor was not, as we had at first supposed, a pile of fallen

fragments, but

one solid boulder which had come down bodily from above. To remove this

was

impossible. We had no tools to cut or break it, and it was both wider

and

higher than the doorway. Even to clear away the sand which rose behind

it to

the ceiling would have taken a long time, and have caused the

inevitable injury

to the paintings around. Already the brilliancy of the colour was

marred where

the men had leaned their backs, all wet with perspiration, against the

walls. Seeing,

therefore, that three-fourths of the decorations were now

uncovered, and that behind the fallen block there appeared to be no

subject of

great size and importance, we made up our minds to carry the work no

further. Meanwhile,

we had great fun at luncheon with our Nubian sheik – a tall,

well-featured man with much natural dignity of manner. He was well

dressed,

too, and wore a white turban most symmetrically folded; a white vest

buttoned

to the throat; a long loose robe of black serge; an outer robe of fine

black

cloth with hanging sleeves and a hood; and on his feet, white stockings

and

scarlet morocco shoes. When brought face to face with a knife and fork,

his

embarrassment was great. He was, it seemed, too grand a personage to

feed

himself. He must have a “feeder;” as the great man of the

Middle Ages had a

“taster.” Talhamy accordingly, being promoted to this

office, picked out choice

bits of mutton and chicken with his fingers, dipped pieces of bread in

gravy,

and put every morsel into our guest’s august mouth, as if the

said guest were a

baby. The sweets

being served, the little lady, L.-----, and the writer took him in

hand, and fed him with all kinds of jams and preserved fruits.

Enchanted with

these attentions, the poor man ate till he could eat no longer; then

laid his

hand pathetically over the region next his heart, and cried for mercy.

After

luncheon, he smoked his chibouque, and coffee was served. Our coffee

did not

please him. He tasted it, but immediately returned the cup, telling the

waiter

with a grimace, that the berries were burned and the coffee weak. When,

however, we apologised for it, he protested with Oriental insincerity

that it

was excellent. To amuse

him was easy, for he was interested in everything; in L.-----’s

field-glass, in the painter’s accordion, in the piano, and the

lever corkscrew.

With some eau-de-Cologne he was also greatly charmed, rubbing it on his

beard

and inhaling it with closed eyes, in a kind of rapture. To make talk

was, as

usual, the great difficulty. When he had told us that his eldest son

was

Governor of Derr; that his youngest was five years of age; that the

dates of

Derr were better than the dates of Wady Halfeh; and that the Nubian

people were

very poor, he was at the end of his topics. Finally, he requested us to

convey

a letter from him to Lord D—, who had entertained him on board

his dahabeeyah

the year before. Being asked if he had brought his letter with him, he

shook

his head, saying:– “Your dragoman shall write it.” So paper

and a reed-pen were produced, and Talhamy wrote to dictation as

follows:– RASHWAN

EBN

HASSAN EL KASHEF.”

A model

letter this; brief, and to the point. Our urbane

and gentlemanly sheik was, however, not quite so charming

when it came to settling time. We had sent at first for fifty men, and

the

price agreed upon was five piastres, or about a shilling English, for

each man

per day. In answer to this call, there first came forty men for half a

day;

then a hundred men for a whole day, or what was called a whole day; so

making a

total of six pounds due for wages. But the descendant of the Kashefs

would hear

of nothing so commonplace as the simple fulfilment of a straightforward

contract. He demanded full pay for a hundred men for two whole days, a

gun for

himself, and a liberal bakshîsh in cash. Finding he had asked

more than he had

any chance of getting, he conceded the question of wages, but stood out

for a

game-bag and a pair of pistols. Finally, he was obliged to be content

with the

six pounds for his men, and for himself two pots of jam, two boxes of

sardines,

a bottle of eau-de-Cologne, a box of pills, and half-a-sovereign. By four

o’clock he and his followers were gone, and we once more had the

place to ourselves. So long as they were there it was impossible to do

anything, but now, for the first time, we fairly entered into

possession of our

newly found treasure. All the

rest of that day, and all the next day, we spent at work in and

about the speos. L.----- and the little lady took their books and knitting

there,

and made a little drawing-room of it. The writer copied paintings and

inscriptions. The mdle Man and the painter took measurements and

surveyed the

ground round about, especially endeavouring to make out the plan of

certain

fragments of wall, the foundations of which were yet traceable. A careful

examination of these ruins, and a little clearing of the sand

here and there, led to further discoveries. They found that the speos

had been

approached by a large outer hall built of sun-dried brick, with one

principal

entrance facing the Nile, and two side-entrances facing northwards. The

floor

was buried deep in sand and débris, but enough of the walls

remained above the

surface to show that the ceiling had been vaulted and the

side-entrances

arched. The

southern boundary wall of this hall, when the surface sand was

removed, appeared to be no less than 20 feet in thickness. This was not

in

itself so wonderful, there being instances of ancient Egyptian

crude-brick

walls which measure 80 feet in thickness;1 but it was

astounding as

compared with the north, east, and west walls, which measured only 3

feet.

Deeming it impossible that this mass could be solid throughout, the idle man

set to work with a couple of sailors to probe the centre part of it,

and it

soon became evident that there was a hollow space about three feet in

width

running due east and west down not quite exactly the middle of the

structure. All at

once the idle man thrust his fingers into a skull! This was

such an amazing and unexpected incident, that for the moment he

said nothing, but went on quietly displacing the sand and feeling his

way under

the surface. The next instant his hand came in contact with the edge of

a clay

bowl, which he carefully withdrew. It measured about four inches in

diameter,

was hand-moulded, and full of caked sand. He now proclaimed his

discoveries,

and all ran to help in the work. Soon a second and smaller skull was

turned up,

then another bowl, and then, just under the place from which the bowls

were

taken, the bones of two skeletons all detached, perfectly desiccated,

and

apparently complete. The remains were those of a child and a small

grown person

– probably a woman. The teeth were sound; the bones wonderfully

delicate and

brittle. As for the little skull (which had fallen apart at the

sutures), it

was pure and fragile in texture as the cup of a water-lily. We laid

the bones aside as we found them, examining every handful of

sand, in the hope of discovering something that might throw light upon

the

burial. But in vain. We found not a shred of clothing, not a bead, not

a coin,

not the smallest vestige of anything that might help one to judge

whether the

interment had taken place a hundred years ago or a thousand. We now

called up all the crew, and went on excavating downwards into

what seemed to be a long and narrow vault measuring some fifteen feet

by three. After-reflection

convinced us that we had stumbled upon a chance Nubian

grave, and that the bowls (which at first we absurdly dignified with

the name

of cinerary urns) were but the usual water-bowls placed at the heads of

the

dead. But we were in no mood for reflection at the time. We made sure

that the speos was a mortuary chapel; that the vault was a vertical pit leading

to a

sepulchral chamber; and that at the bottom of it we should find . . . .

who

could tell what? Mummies, perhaps, and sarcophagi, and funerary

statuettes, and

jewels, and papyri, and wonders without end! That these uncared-for

bones

should be laid in the mouth of such a pit scarcely occurred to us as an

incongruity. Supposing them to be Nubian remains, what then? If a

modern Nubian

at the top, why not an ancient Egyptian at the bottom? As the

work of excavation went on, however, the vault was found to be

entered by a steep inclined plane. Then the inclined plane turned out

to be a

flight of much worn and very shallow stairs. These led down to a small

square

landing, some twelve feet below the surface, from which landing an

arched

doorway2 and passage opened into the fore-court of the speos. Our

sailors had great difficulty in excavating this part, in consequence of

the

weight of superincumbent sand and débris on the side next the speos. By shoring

up the ground, however, they were enabled completely to clear the

landing,

which was curiously paved with cones of rude pottery like the bottoms

of

amphoræ. These cones, of which we took out some twenty-eight or

thirty, were

not in the least like the celebrated funerary cones found so abundantly

at

Thebes. They bore no stamp, and were much shorter and more lumpy in

shape.

Finally, the cones being all removed, we came to a compact and solid

floor of

baked clay. The painter, meanwhile, had also been at work. Having traced the circuit

and drawn out a ground-plan, he came to the conclusion that the whole

mass

adjoining the southern wall of the speos was in fact composed of the

ruins of a

pylon, the walls of which were seven feet in thickness, built in

regular

string-courses of moulded brick, and finished at the angles with the

usual torus, or round

moulding. The

superstructure, with its chambers, passages, and top cornice, was gone;

and

this part with which we were now concerned was merely the basement, and

included the bottom of the staircase. The painter’s ground-plan demolished all our hopes at one fell swoop.

The vault was a vault no longer. The staircase led to no sepulchral

chamber.

The brick floor hid no secret entrance. Our mummies melted into thin

air, and

we were left with no excuse for carrying on the excavations. We were

mortally

disappointed. In vain we told ourselves that the discovery of a large

brick

pylon, the existence of which had been unsuspected by preceding

travellers, was

an event of greater importance than the finding of a tomb. We had set

our

hearts on the tomb; and I am afraid we cared less than we ought for the

pylon. Having

traced thus far the course of the excavations and the way in

which one discovery led step by step to another, I must now return to

the speos, and, as accurately as I can, describe it, not only from my notes

made on

the spot, but by the light of such observations as I afterwards made

among

structures of the same style and period. I must, however, premise that,

not

being able to go inside while the excavators were in occupation, and

remaining

but one whole day at Abou Simbel after the work was ended, I had but

short time

at my disposal. I would gladly have made coloured copies of all the

wall-paintings, but this was impossible. I therefore was obliged to be

content

with transcribing the inscriptions and sketching a few of the more

important

subjects. The

rock-cut chamber which I have hitherto described as a speos, and

which we at first believed to be a tomb, was in fact neither the one

nor the

other. It was the adytum of a partly built, partly excavated monument

coeval in

date with the great temple. In certain points of design this monument

resembles

the contemporary speos of Bayt-el-Welly. It is evident, for instance,

that the

outer halls of both were originally vaulted; and the much mutilated

sculptures

over the doorway of the excavated chamber at Abou Simbel are almost

identical

in subject and treatment with those over the entrance to the excavated

parts of

Bayt-el-Welly. As regards general conception, the Abou Simbel monument

comes

under the same head with the contemporary temples of Derr, Gerf

Hossayn, and

Wady Sabooah; being in a mixed style which combines excavation with

construction. This style seems to have been peculiarly in favour during

the reign

of Rameses II. Situate at

the south-eastern angle of the rock, a little way beyond the

façade of the great temple, this rock-cut adytum and hall of

entrance face south-east

by east, and command much the same view that is commanded higher up by

the Temple

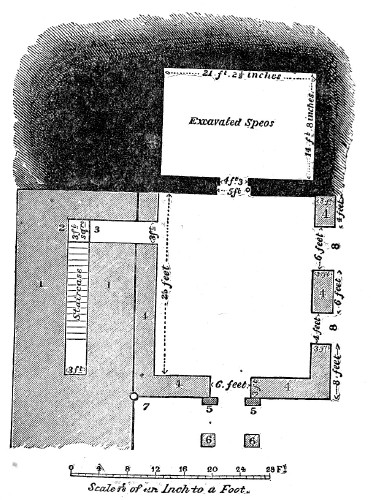

of Hathor. The adytum, or excavated speos, measures 21 feet 2 1/2

inches in

breadth by 14 feet 8 inches in length. The height from floor to ceiling

is

about 12 feet. The doorway measures 4 feet 3 1/2 inches in width; and

the outer

recess for the door-frame, 5 feet. Two large circular holes, one in the

threshold and the other in the lintel, mark the place of the pivot on

which the

door once swung. It is not

very easy to measure the outer hall in its present ruined and

encumbered state; but as nearly as we could judge its dimensions are as

follows: – Length, 25 feet; width, 22 1/2 feet; width of

principal entrance

facing the Nile, 6 feet; width of two side entrances 4 feet and 6 feet

respectively; thickness of crude-brick walls, 3 feet. Engaged in the

brickwork

on either side of the principal entrance to this hall are two stone

door-jambs;

and some six or eight feet in front of these, there originally stood

two stone

hawks on hieroglyphed pedestals. One of these hawks we found in situ, the other lay some

little distance

off, and the painter (suspecting nothing of these after-revelations)

had used

it as a post to which to tie one of the main ropes of his sketching

tent. A

large hieroglyphed slab, which I take to have formed part of the door,

lay

overturned against the side of the pylon some few yards nearer the

river. As far as

the adytum and outer hall are concerned, the accompanying

ground-plan – which is in part founded on my own measurements,

and in part

borrowed from the ground-plan drawn out by the painter – may be

accepted as

tolerably correct. But with regard to the pylon, I can only say with

certainty

that the central staircase is three feet in width, and that the walls

on each

side of it are seven feet in thickness. So buried is it in

débris and sand, that

even to indicate where the building ends and the rubbish begins at the

end next

the Nile, is impossible. This part is therefore left indefinite in the

ground-plan.

So far as

we could see, there was no stone revêtement upon the inner

side of the walls of the pronaos. If anything of the kind ever existed,

some

remains of it would probably be found by thoroughly clearing the area;

an

interesting enterprise for any who may have leisure to undertake it. I have now

to speak of the decorations of the adytum, the walls of

which, from immediately under the ceiling to within three feet of the

floor,

are covered with religious subjects elaborately sculptured in

bas-relief,

coated as usual with a thin film of stucco, and coloured with a

richness for

which I know no parallel, except in the tomb of Seti I3 at

Thebes.

Above the level of the drifted sand, this colour was as brilliant in

tone and

as fresh in surface as on the day when it was transferred to those

walls from

the palette of the painter. All below that level, however, was dimmed

and

damaged.

The

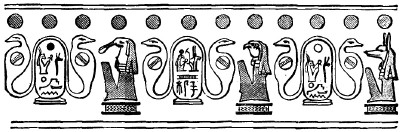

ceiling is surrounded by a frieze of cartouches supported by sacred

asps; each cartouche, with its supporters, being divided from the next

by a

small sitting figure. These figures, in other respects uniform, wear

the symbolic

heads of various gods – the cow-head of Hathor, the ibis-head of

Thoth, the

hawk-head of Horus, the jackal-head of Anubis, etc. etc. The cartouches

contain

the ordinary style and title of Rameses II (Ra-user-ma Sotep-en-Ra

Rameses

Mer-Amen), and are surmounted by a row of sun-disks. Under each sitting

god is

depicted the phonetic hieroglyph signifying Mer,

or Beloved. By means of this device, the whole frieze assumes the

character of

a connected legend, and describes the king not only as beloved of Amen,

but as

Rameses beloved of Hathor, of Thoth, of Horus – in short, of each god depicted

in the series. These gods

excepted, the frieze is almost identical in design with the

frieze in the first hall of the great temple. WEST WALL.4

To the

left of the Horus ensign, seated back-to-back with Ra upon a

similar throne, sits Amen-Ra – of all Egyptian gods the most

terrible to look

upon – with his blue-black complexion, his corselet of golden

chain-armour, and

his head-dress of towering plumes.7 Here the wonderful

preservation

of the surface enabled one to see by what means the ancient artists

were wont

to produce this singular blue-black effect of colour. It was evident

that the

flesh of the god had first been laid in with dead black, and then

coloured over

with a dry, powdery cobalt-blue, through which the black remained

partially

visible. He carries in one hand the ankh, and in the other the

greyhound-headed

sceptre.

SOUTH WALL. The

subjects represented on this wall are as follows:– 1.

Rameses, life-size, presiding over a table of offerings. The king

wears upon his head the klaft,

or

head-cloth, striped gold and white, and decorated with the uræus.

The table is

piled in the usual way with flesh, fowl, and flowers. The surface being

here

quite perfect, the details of these objects are seen to be rendered

with

suprising minuteness. Even the tiny black feather-stumps of the plucked

geese

are given with the fidelity of Chinese art; while a red gash in the

breast of

each shows in what way it was slain for the sacrifice. The loaves are

shaped

precisely like the so-called “cottage-loaves” of to-day,

and have the same

little depression in the top, made by the baker’s finger. Lotus

and papyrus

blossoms in elaborate bouquet-holders crown the pile. 2. Two

tripods of light and elegant design, containing flowers. 3. The

Bari, or sacred boat, painted gold-colour, with the usual veil

half-drawn across the naos, or shrine; the prow of the boat being

richly

carved, decorated with the Uta9 or symbolic eye, and

preceded by a

large fan of ostrich feathers. The boat is peopled with small black

figures,

one of which kneels at the stern; while a sphinx couchant, with black

body and

human head, keeps watch at the prow. The sphinx symbolises the king. On this

wall, in a space between the sacred boat and the figure of

Rameses, occurs the following inscription, sculptured in high relief

and

elaborately coloured:–

TRANSLATION.

Said by

Thoth, the Lord of Sesennu10 [residing] in Amenheri,11

– I give to thee an everlasting sovereignty over the

Two Countries, O Son

of [my] body, Beloved, Ra-user-ma Sotep-en-Ra, acting as propitiator of

thy Ka. I give to thee

myriads of festivals of

Rameses beloved of Amen, Ra-user-ma Sotep-en-Ra, as prince of every

place where

the sun-disk revolves. The beautiful living god, maker of beautiful

things for

[his] father Thoth Lord of Sesennu [residing] in Amenheri. He made

mighty and

beautiful monuments for ever facing the eastern horizon of heaven. The

meaning of which is that Thoth, addressing Rameses II, then living

and reigning, promises him a long life and many anniversaries of his

jubilee,12 in return for the works made in his

(Thoth’s) honour

at Abou Simbel and

elsewhere. NORTH WALL.

At the

upper end of this wall is depicted a life-sized female figure

wearing an elaborate blue head-dress surmounted by a disk and two

ostrich

feathers. She holds in her right hand the ankh, and in her left the

jackal-headed sceptre. This not being the sceptre of a goddess, and the

head-dress

resembling that of the Queen as represented on the façade of the temple of

Hathor, I conclude we have here a portrait of Nefertari corresponding

to the

portrait of Rameses on the opposite wall. Near her stands a table of

offerings,

on which, among other objects, are placed four vases of a rich blue

colour

traversed by bands of yellow. They perhaps represent the kind of glass

known as

the false murrhine.13 Each of these vases contains an

object like a

pine, the ground-colour of which is deep yellow, patterned over with

scale-like

subdivisions in vermilion. We took them to represent grains of maize

pyramidally piled. Lastly, a

pendant to that on the opposite wall, comes the sacred Bari.

It is, however, turned the reverse way, with its prow towards the east;

and it

rests upon an altar, in the centre of which are the cartouches of

Rameses II

and a small hieroglyphic inscription signifying: “Beloved by

Amen-Ra, King of

the gods resident in the Land of Kenus.”14 Beyond

this point, at the end nearest the north-east corner of the

chamber, the piled sand conceals whatever else the wall may contain in

the way

of decoration. EAST WALL.

If the

east wall is decorated like the others (which may be taken for

granted), its tableaux and inscriptions are hidden behind the sand

which here

rises to the ceiling. The doorway also occurs in this wall, occupying a

space 4

feet 3 1/2 inches in width on the inner side. One of the

most interesting incidents connected with the excavation of

this little adytum remains yet to be told. I have

described the female figure at the upper end of the north wall,

and how she holds in her right hand the ankh and in her left the

jackal-headed

sceptre. The hand that holds the ankh hangs by her side; the hand that

holds

the sceptre is half raised. Close under this upraised hand, at a height

of

between three and four feet from the actual level of the floor, there

were

visible upon the uncoloured surface of the original stucco several

lines of

free-hand writing. This writing was laid on, apparently, with the

brush, and

the ink, if ever it had been black, had now become brown. Five long

lines and

three shorter lines were uninjured. Below these were traces of other

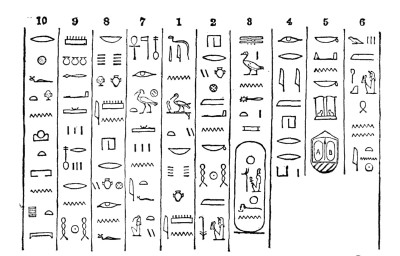

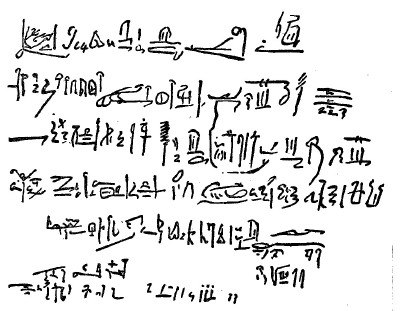

fragmentary lines, almost obliterated by the sand. We knew at once that this quaint faint writing must be in either the hieratic or demotic hand. We could distinguish, or thought we could distinguish, in its vague outlines of forms already familiar to us in the hieroglyphs – abstracts, as it were, of birds and snakes and boats. There could be no doubt, at all events, that the thing was curious; and we set it down in our own minds as the writing of either the architect or decorator of the place. Anxious to

make, if possible, an exact facsimile of this inscription,

the Writer copied it three times. The last and best of these copies is

here

reproduced in photolithography, with a translation from the pen of the

late Dr.

Birch. We all know how difficult it is to copy correctly in a language

of which

one is ignorant; and the tiniest curve or dot omitted is fatal to the

sense of

these ancient characters. In the present instance, notwithstanding the

care

with which the transcript was made, there must still have been errors;

for it

has been found undecipherable in places; and in these places there

occur

inevitable lacunæ. Enough, however, remains to show that the lines were written, not as we had supposed by the artist, but by a distinguished visitor, whose name unfortunately is illegible. This visitor was a son of the Prince of Kush, or as it is literally written, the Royal Son of Kush; that being the official title of the Governor of Ethiopia.19 As there were certainly eight governors of Ethiopia during the reign of Rameses II (and perhaps more, whose names have not reached us), it is impossible even to hazard a guess at the parentage of our visitor. We gather, however, that he was sent hither to construct a road; also that he built transport boats; and that he exercised priestly functions in that part of the temple which was inaccessible to all but dignitaries of the sacerdotal order.

HIERATIC INSCRIPTION,

Site,

inscriptions, and decorations taken into account, there yet

remains this question to be answered:– What was

the nature and character of the monument just described? It

adjoined a pylon, and, as we have seen, consisted of a vaulted

pronaos in crude brick, and an adytum excavated in the rock. On the

walls of

this adytum are depicted various gods with their attributes, votive

offerings,

and portraits of the king performing acts of adoration. The Bari, or

ark, is

also represented upon the north and south walls of the adytum. These

are

unquestionably the ordinary features of a temple, or chapel. On the

other hand, there must be noted certain objections to these premises.

It seemed to us that the pylon was built first, and that the south

boundary

wall of the pronaos, being a subsequent erection, was supported against

the

slope of the pylon as far as where the spring of the vaulting began.

Besides

which, the pylon would have been a disproportionately large adjunct to

a little

monument the entire length of which, from the doorway of the pronaos to

the

west wall of the adytum, was less than 47 feet. We therefore concluded

that the

pylon belonged to the large temple, and was erected at the side,

instead of in

front of the façade, on account of the very narrow space between

the mountain

and the river.20 The pylon

at Kom Ombo is, probably for the same reason, placed at the

side of the temple and on a lower level. To those who might object that

a brick

pylon would hardly be attached to a temple of the first class, I would

observe

that the remains of a similar pylon are still to be seen at the top of

what was

once the landing-place leading to the great temple at Wady Halfeh. It

may,

therefore, be assumed that this little monument, although connected

with the

pylon by means of a doorway and staircase, was an excrescence of later

date. Being an

excrescence, however, was it, in the strict sense of the word,

a temple? Even this

seems to be doubtful. In the adytum there is no trace of any

altar – no fragment of stone dais or sculptured image – no

granite shrine, as

at Philæ – no sacred recess, as at Denderah. The standard

of Horus Aroëris,

engraven on page 340, occupies the centre place upon the wall facing

the

entrance, and occupies it, not as a tutelary divinity, but as a

decorative

device to separate the two large subjects already described. Again, the gods

represented in these subjects are Ra and Amen-Ra, the tutelary gods of

the great temple; but if we turn to the dedicatory inscription on page 344

we find

that Thoth, whose image never occurs at all upon the walls21 (unless

as one of the little gods in the cornice), is really the presiding

deity of the

place. It is he who welcomes Rameses and his offerings; who

acknowledges the

“glory” given to him by his beloved son; and who, in return

for the great and

good monuments erected in his honour, promises the king that he shall

be given

an “everlasting sovereignty over the Two Countries.” Now Thoth

was, par excellence,

the god of Letters. He is styled the Lord of Divine Words; the Lord of

the

Sacred Writings; the Spouse of Truth. He personifies the Divine

Intelligence.

He is the patron of art and science; and he is credited with the

invention of

the alphabet. In one of the most interesting of Champollion’s

letters from

Thebes,22 he relates how, in the fragmentary ruins of the

western

extremity of the Ramesseum, he found a doorway adorned with the figures

of

Thoth and Safek; Thoth as the god of Literature, and Safek inscribed

with the

title of Lady President of the Hall of Books. At Denderah, there is a

chamber

especially set apart for the sacred writings, and its walls are

sculptured all

over with a catalogue raisonnée of the manuscript treasures of

the Temple. At

Edfu, a kind of closet built up between two pillars of the Hall of

Assembly was

reserved for the same purpose. Every Temple, in short, had its library;

and as

the Egyptian books – being written on papyrus or leather, rolled

up, and stored

in coffers – occupied but little space, the rooms appropriated to

this purpose

were generally small. It was Dr.

Birch’s opinion that our little monument may have been the

library of the Great Temple of Abou Simbel. This being the case, the

absence of

an altar, and the presence of Ra and Amen-Ra in the two principal

tableaux, are

sufficiently accounted for. The tutelary deity of the Great Temple and

the

patron deity of Rameses II would naturally occupy, in this subsidiary

structure, the same places that they occupy in the principal one; while

the

library, though in one sense the domain of Thoth, is still under the

protection

of the gods of the Temple to which it is an adjunct. I do not

believe we once asked ourselves how it came to pass that the

place had remained hidden all these ages long; yet its very freshness

proved

how early it must have been abandoned. If it had been open in the time

of the

successors of Rameses II, they would probably, as elsewhere, have

interpolated

inscriptions and cartouches, or have substituted their own cartouches

for those

of the founder. If it had been open in the time of the Ptolemies and

Cæsars,

travelling Greeks and learned Romans, and strangers from Byzantium and

the

cities of Asia Minor, would have cut their names on the door-jambs and

scribbled ex-votos on the walls. If it had been open in the days of

Nubian

Christianity, the sculptures would have been coated with mud, and

washed with

lime, and daubed with pious caricatures of St. George and the Holy

Family. But

we found it intact – as perfectly preserved as a tomb that had

lain hidden

under the rocky bed of the desert. For these reasons I am inclined to

think

that it became inaccessible shortly after it was completed. There can

be little

doubt that a wave of earthquake passed, during the reign of Rameses II,

along

the left bank of the Nile, beginning possibly above Wady Halfeh, and

extending

at least as far north as Gerf Hossayn. Such a shock might have wrecked

the temple at Wady Halfeh, as it dislocated the pylon of Wady Sabooah, and

shook

the built-out porticoes of Derr and Gerf Hossayn; which last four temples, as

they do not, I believe, show signs of having been added to by later

Pharaohs,

may be supposed to have been abandoned in consequence of the ruin which

had

befallen them. Here, at all events, it shook the mountain of the great temple,

cracked one of the Osiride columns of the First Hall,23 shattered

one of the four great Colossi, more or less injured the other three,

flung down

the great brick pylon, reduced the pronaos of the library to a heap of

ruin,

and not only brought down part of the ceiling of the excavated adytum,

but rent

open a vertical fissure in the rock, some 20 or 25 feet in length. With so

much irreparable damage done to the great temple, and with so

much that was reparable calling for immediate attention, it is no

wonder that

these brick buildings were left to their fate. The priests would have

rescued

the sacred books from among the ruins, and then the place would have

been

abandoned. So much by

way of conjecture. As hypothesis, a sufficient reason is

perhaps suggested for the wonderful state of preservation in which the

little

chamber had been handed down to the present time. A rational

explanation is

also offered for the absence of later cartouches, of Greek and Latin

ex-votos,

of Christian emblems, and of subsequent mutilation of every kind. For,

save

that one contemporary visitor – the son of the Royal Son of Kush

– the place

contained, when we opened it, no record of any passing traveller, no

defacing

autograph of tourist, archæologist, or scientific explorer.

Neither Belzoni nor

Champollion had found it out. Even Lepsius had passed it by. It happens

sometimes that hidden things, which in themselves are easy to

find, escape detection because no one thinks of looking for them. But

such was

not the case in this present instance. Search had been made here again

and

again; and even quite recently. It seems

that when the Khedive24 entertains distinguished

guests and sends them in gorgeous dahabeeyahs up the Nile, he grants

them a

virgin mound, or so many square feet of a famous necropolis; lets them

dig as

deep as they please; and allows them to keep whatever they may find.

Sometimes

he sends out scouts to beat the ground; and then a tomb is found and

left

unopened, and the illustrious visitor is allowed to discover it. When

the

scouts are unlucky, it may even sometimes happen that an old tomb is

re-stocked; carefully closed up; and then, with all the charm of

unpremeditation, re-opened a day or two after. Now Sheykh

Rashwan Ebn Hassan el Kashef told us that in 1869, when the

Empress of the French was at Abou Simbel, and again when the Prince and

Princess of Wales came up in 1872, after the Prince’s illness, he

received

strict orders to find some hitherto undiscovered tomb,25 in

order

that the Khedive’s guests might have the satisfaction of opening

it. But, he

added, although he left no likely place untried among the rocks and

valleys on

both sides of the river, he could find nothing. To have unearthed such

a Birbeh

as this, would have done him good service with the Government, and have

ensured

him a splendid bakhshîsh from Prince or Empress. As it was, he

was reprimanded

for want of diligence, and he believed himself to have been out of

favour ever

since. I may here

mention – in order to have done with this subject – that

besides being buried outside to a depth of about eight feet, the adytum

had

been partially filled inside by a gradual infiltration of sand from

above. This

can only have accumulated at the time when the old sand-drift was at

its

highest. That drift, sweeping in one unbroken line across the front of

the great temple, must at one time have risen here to a height of twenty

feet above

the present level. From thence the sand had found its way down the

perpendicular fissure already mentioned. In the corner behind the door,

the

sand-pile rose to the ceiling, in shape just like the deposit at the

bottom of

an hour-glass. I am informed by the Painter that when the top of the

doorway

was found and an opening first effected, the sand poured out from within, like water

escaping from an

opened sluice. Here,

then, is positive proof (if proof were needed) that we were first

to enter the place, at all events since the time when the great

sand-drift rose

as high as the top of the fissure. The

Painter wrote his name and ours, with the date (February 16th,

1874), on a space of blank wall over the inside of the doorway; and

this was

the only occasion upon which any of us left our names upon an Egyptian

monument. On arriving at Korosko, where there is a post-office, he also

despatched a letter to the “Times,” briefly recording the

facts here related.

That letter, which appeared on the 18th of March following, is

reprinted in the

Appendix at the end of this book. I am told that our names are partially effaced, and that the wall-paintings which we had the happiness of admiring in all their beauty and freshness, are already much injured. Such is the fate of every Egyptian monument, great or small. The tourist carves it all over with names and dates, and in some instances with caricatures. The student of Egyptology, by taking wet paper “squeezes,” sponges away every vestige of the original colour. The “collector” buys and carries off everything of value that he can get; and the Arab steals for him. The work of destruction, meanwhile, goes on apace. There is no one to prevent it; there is no one to discourage it. Every day, more insciptions are mutilated – more tombs are rifled – more paintings and sculptures are defaced. The Louvre contains a full-length portrait of Seti I, cut out bodily from the walls of his sepulchre in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. The Museums of Berlin, of Turin, of Florence, are rich in spoils which tell their own lamentable tale. When science leads the way, is it wonderful that ignorance should follow? _______________________1 The

enclosure-wall of the great temple of Tanis is 80 feet thick. See "Tanis," Part I, by W. M. F.

Petrie;

published by the Committee of the Egypt Exploration Fund, 1885. [Note

to second edition.] 2 It was

long believed that the Egyptians were ignorant of the principle of the

arch.

This, however, was not the case. There are brick arches of the time of

Rameses

II behind the Ramesseum at Thebes, and elsewhere. Still, arches are

rare in

Egypt. We filled in and covered the arch again, and the greater part of

the

staircase, in order to preserve the former. 3 Commonly

known as Belzoni’s Tomb. 4 I write of

these walls, for convenience, as north, south, east, and west, as one is so

accustomed to

regard the position of buildings parallel with the river; but the

present

monument, as it is turned slightly southward round the angle of the

rock,

really stands southeast by east, instead of east and west like the large temple. 5 Horus

Aroëris. – “Celui-ci, qui semble avoir

été frère d’Osiris, porte une tête

d’épervier coiffée du pschent. Il est presque

complètement identifié avec le

soleil dans la plupart des lieux où il était

adoré, et il en est de même très

souvent pour Horus, fils d’Isis.” – "Notice

Sommaire des Monuments du Louvre," 1873. De Rougé. In

the present

instance, this god seems to have been identified with Ra. 6 “Le

sceptre à tête de lévrier, nommé à

tort sceptre à tête de coucoupha, était

porté par les dieux.” – "Dic. d’Arch.

Egyptienne:" P. Pierret; Paris, 1875. 7 Amen of

the blue complexion is the most ancient type of this god. He here

represents

divine royalty, in which character his title is: “Lord of the

Heaven, of the

Earth, of the Waters, and of the Mountains.” “Dans ce

rôle de roi du monde,

Amon a les chairs peintes en bleu pour indiquer sa nature

céleste; et lorsqu’il

porte le titre de Seigneur des Trônes, il est

représenté assis, la couronne en

tête: d’ordinaire il est debout.” – "Étude

des Monuments de Karnak." De Rougé. "Mélanges

d’Archeologie," vol. i. 1873. There were

almost as many varieties of Amen in Egypt as there are

varieties of the Madonna in Italy or Spain. There was an Amen of

Thebes, an

Amen of Elephantine, an Amen of Coptos, an Amen of Chemmis (Panopolis),

an Amen

of the Resurrection, Amen of the Dew, Amen of the Sun (Amen-Ra), Amen

Self-created, etc. etc. Amen and Khem were doubtless identical. It is

an

interesting fact that our English words, chemical, chemist, chemistry,

etc.,

which the dictionaries derive from the Arabic al-kimia,

may be traced back a step farther to the Panopolitan name of this most

ancient god of the Egyptians, Khem (Gr. Pan; Latin, Priapus), the deity of

plants and

herbs and of the creative principle. A cultivated Egyptian would,

doubtless,

have regarded all these Amens as merely local or symbolical types of a

single

deity. 8 The

material of this blue helmet, so frequently depicted on the monuments, may have been the Homeric

Kuanos, about

which so much doubt and conjecture have gathered, and which Mr.

Gladstone

supposes to have been a metal. – (See "Juventus

Mundi," chap. xv. p. 532.) A paragraph in The Academy (June 8, 1876)

gives the following particulars

of certain perforated lamps of a “blue metallic substance,”

discovered at

Hissarlik by Dr. Schliemann, and there found lying under the copper

shields to

which they had probably been attached. “An analytical examination

by Landerer (Berg.

Hüttenm. Zeitung, xxxix. 430) has

shown them to be sulphide of copper. The art of colouring the metal was

known

to the coppersmiths of Corinth, who plunged the heated copper into the

fountain

of Peirene. It appears not impossible that this was a sulphur spring,

and that

the blue colour may have been given to the metal by plunging it in a

heated

state into the water and converting the surface into copper

sulphide.” It is to

be observed that the Pharaohs are almost always represented

wearing this blue helmet in the battle-pieces, and that it is

frequently

studded with gold rings. It must therefore have been of metal. If not

of

sulphuretted copper, it may have been made of steel, which, in the

well-known

instance of the butcher’s sharpener, as well as in

representations of certain

weapons, is always painted blue upon the monuments. 9 “This eye,

called uta, was

extensively used

by the Egyptians both as an ornament and amulet during life, and as a

Sepulchral amulet. They are found in the form of right eyes and left

eyes, and

they symbolise the eyes of Horus, as he looks to the north and south horizons

in his

passage from east to west, i.e.

from

sunrise to sunset.” M.

Grebaut, in his translation of a hymn to Amen-Ra, observes: “Le

soleil marchant d’Orient en Occident éclaire de ses deux

yeux les deux régions

du Nord et du Midi.” – "Révue

Arch."

vol. xxv. 1873; p. 387. 10 Sesennu – Eshmoon

or Hermopolis. 11 Amenheri – Gebel

Addeh. 12 These

jubilees, or festivals of thirty years, were religious jubilees in

celebration

of each thirtieth

anniversary of

the accession of the reigning Pharaoh. 13 There are,

in the British Museum, some bottles and vases of this description,

dating from

the eighteenth dynasty; see Case E, Second

Egyptian Room. They are of dark blue translucent glass,

veined with

waving lines of opaque white and yellow. 14 Kenus – Nubia. 15 i.e. Ammon Ra, the sun god,

in

conjunction or identification with Har-em-aχu, of

Horus-on-the-Horizon, another solar deity. 16 The

primæval god. 17 Inner

place, or sanctuary. 18 Ethiopia. 19 Governors

of Ethiopia bore this title, even though they did not themselves belong

to the

family of the Pharaoh. It is a

curious fact that one of the Governors of Ethiopia during the

reign of Rameses II was called Mes, or Messou, signifying son, or child

– which

is in fact Moses. Now

the Moses

of the Bible was adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter, “became to

her as a son,” was

instructed in the wisdom of the Egyptians, and married a Kushite woman,

black

but comely. It would perhaps be too much to speculate on the

possibility of his

having held the office of Governor, or Royal Son of Kush. 20 At about

an equal distance to the north of the great temple, on the verge of the

bank,

is a shapeless block of brick ruin, which might possibly, if

investigated, turn

out to be the remains of a second pylon corresponding to this which we

partially uncovered to the south. 21 He may,

however, be represented on the north wall, where it is covered by the

sand-heap. 22 Letter

XIV. p. 235. "Nouvelle Ed.,"

Paris,

1868. 23 That this

shock of earthquake occurred during the lifetime of Rameses II seems to

be

proven by the fact that, where the Osiride column is cracked across, a

wall has

been built up to support the two last pillars to the left at the upper

end of

the great hall, on which wall is a large stela covered with an

elaborate

hieroglyphic inscription, dating from the thirty-fifth year, and the 13th day

of the

month of Tybi, of the reign of

Rameses II.

The right arm of the external colossus, to the right of the great

doorway, has

also been suported by the introduction of an arm to his throne, built

up of

square blocks; this being the only arm to any of the thrones. Miss

Martineau

detected a restoration of part of the lower jaw of the northernmost

colossus,

and also a part of the dress of one of the Osiride statues in the great

hall. I

have in my possession a photograph taken at a time when the sand was

several

feet lower than at present, which shows that the right leg of the

northernmost

colossus is also a restoration on a gigantic scale, being built up,

like the

throne-arm, in great blocks, and finished, most probably, afterwards. 24 This

refers to the Ex-Khedive, Ismail Pasha, who ruled Egypt at the time

when this

book was written and published. [Note to second edition.] 25 There are tombs in some of the ravines behind the temples, which, however, we did not see. |

||||||||||||