| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER

V. BEDRESHAYN

TO MINIEH. IT is

the

rule of the Nile to hurry up the river as fast as possible, leaving the

ruins

to be seen as the boat comes back with the current; but this, like many

another

canon, is by no means of universal application. The traveller who

starts late

in the season has, indeed, no other course open to him. He must press

on with

speed to the end of his journey, if he would get back again at low Nile

without

being irretrievably stuck on a sand-bank till the next inundation

floats him

off again. But for those who desire not only to see the monuments, but

to

follow, however superficially, the course of Egyptian history as it is

handed

down through Egyptian art, it is above all things necessary to start

early and

to see many things by the way. For the

history of ancient Egypt goes against the stream. The earliest

monuments lie

between Cairo and Siout, while the latest temples to the old gods are

chiefly

found in Nubia. Those travellers, therefore, who hurry blindly forward

with or

without a wind, now sailing, now tracking, now punting, passing this

place by

night, and that by day, and never resting till they have gained the

farthest

point of their journey, begin at the wrong end and see all their sights

in

precisely inverse order. Memphis and Sakkârah and the tombs

of Beni Hassan

should undoubtedly be visited on the way up. So should El Kâb

and Tell el

Amarna, and the oldest parts of Karnak and Luxor. It is not necessary

to delay

long at any of these places. They may be seen cursorily on the way up,

and be

more carefully studied on the way down; but they should be seen as they

come,

no matter at what trifling cost of present delay, and despite any

amount of

ignorant opposition. For in this way only is it possible to trace the

progression and retrogression of the arts from the pyramid-builders to

the

Cæsars; or to understand at the time, and on the spot, in

what order that vast

and august procession of dynasties swept across the stage of history. For

ourselves, as will presently be seen, it happened that we could carry

only a

part of this programme into effect; but that part, happily was the most

important. We never ceased to congratulate ourselves on having made

acquaintance with the pyramids of Ghîzeh and

Sakkârah before seeing the tombs

of the kings at Thebes; and I feel that it is impossible to

overestimate the

advantage of studying the sculptures of the tomb of Ti before

one’s taste is

brought into contact with the debased style of Denderah and Esneh. We

began the great book, in short, as it always should be begun – at its

first page; thereby

acquiring just that necessary insight without which many an

after-chapter must

have lost more than half its interest. If I

seem

to insist upon this point, it is because things contrary to custom need

a

certain amount of insistance, and are sure to be met by opposition. No

dragoman, for example, could be made to understand the importance of

historical

sequence in a matter of this kind; especially in the case of a contract

trip.

To him, Khufu, Rameses, and the Ptolemies are one. As for the

monuments, they

are all ancient Egyptian, and one is just as odd and unintelligible as

another.

He cannot quite understand why travellers come so far and spend so much

money

to look at them; but he sets it down to a habit of harmless curiousity

– by

which he profits. The

truth

is, however, that the mere sight-seeing of the Nile demands some little

reading

and organising, if only to be enjoyed. We cannot all be profoundly

learned; but

we can at least do our best to understand what we see – to

get rid of obstacles

– to put the right thing in the right place. For the land of

Egypt is, as I

have said, a great book – not very easy reading, perhaps,

under any

circumstances; but at all events quite difficult enough already without

the

added puzzlement of being read backwards. And now

our next point along the river, as well as our next link in the chain

of early

monuments, was Beni Hassan, with its famous rock-cut tombs of the twelfth

dynasty; and Beni Hassan was still more than a hundred and forty-five

miles

distant. We ought to have gone on again directly – to have

weighed anchor and

made a few miles that very evening on returning to the boats; but we

insisted

on a second day in the same place. This, too, with the favourable wind

still

blowing. It was against all rule and precedent. The captain shook his

head, the

dragoman remonstrated, in vain. “You

will

come to learn the value of a wind, when you have been longer on the

Nile,” said

the latter, with that air of melancholy resignation which he always

assumed

when not allowed to have his own way. He was an indolent good-tempered

man,

spoke English fairly well, and was perfectly manageable; but that air

of

resignation came to be aggravating in time. The M.

B.’s being of the same mind, however, we had our second day,

and spent it at

Memphis. We ought to have crossed over to Turra, and have seen the

great

quarries from which the casing-stones of the pyramids came, and all the

finer

limestone with which the temples and palaces of Memphis were built. But

the

whole mountain-side seemed as if glowing at a white heat on the

opposite side

of the river, and we said we would put off Turra till our return. So we

went

our own way; and Alfred shot pigeons; and the writer sketched

Mitrâhîneh, and

the palms, and the sacred lake of Mena; and the rest grubbed among the

mounds

for treasure, finding many curious fragments of glass and pottery, and

part of

an engraved bronze Apis; and we had a green, tranquil, lovely day,

barren of

incident, but very pleasant to remember. The good

wind continued to blow all that night; but fell at sunrise, precisely

when we

were about to start. The river now stretched away before us, smooth as

glass,

and there was nothing for it, said Reïs Hassan, but tracking.

We had heard of

tracking often enough since coming to Egypt, but without having any

definite

idea of the process. Coming on deck, however, before breakfast, we

found nine

of our poor fellows harnessed to a rope like barge-horses, towing the

huge boat

against the current. Seven of the M. B.’s crew, similarly

harnessed, followed

at a few yards’ distance. The two ropes met and crossed and

dipped into the

water together. Already our last night’s mooring-place was

out of sight, and

the pyramid of Ouenephes stood up amid its lesser brethren on the edge

of the

desert, as if bidding us goodbye. But the sight of the trackers jarred,

somehow, with the placid beauty of the picture. We got used to it, as

one gets

used to everything, in time; but it looked like slaves’ work,

and shocked our

English notions disagreeably. That

morning, still tracking, we pass the pyramids of Dahshûr. A

dilapidated brick

pyramid standing in the midst of them looks like an aiguille of black

rock

thrusting itself up through the limestone bed of the desert. Palms line

the

bank and intercept the view; but we catch flitting glimpses here and

there,

looking out especially for that dome-like pyramid which we observed the

other

day from Sakkârah. Seen in the full sunlight, it looks larger

and whiter, and

more than ever like the roof of the old Palais de Justice far away in

Paris. Thus the

morning passes. We sit on deck writing letters; reading; watching the

sunny

river-side pictures that glide by at a foot’s pace and are so

long in sight.

Palm-groves, sand-banks, patches of fuzzy-headed dura1

and fields of

some yellow-flowering herb, succeed each other. A boy plods along the

bank,

leading a camel. They go slowly; but they soon leave us behind. A

native boat

meets us, floating down side-wise with the current. A girl comes to the

water’s

edge with a great empty jar on her head, and waits to fill it till the

trackers

have gone by. The pigeon-towers of a mud-village peep above a clump of

lebbek

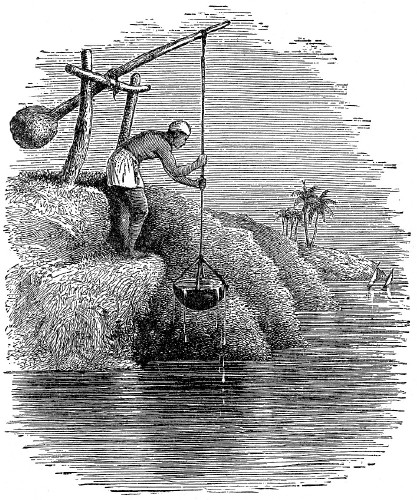

trees, a quarter of a smile inland. Here a solitary brown man, with

only a felt

skull-cap on his head and a slip of scanty tunic fastened about his

loins,

works a shâdûf,2

stooping and rising,

stooping and rising, with the

regularity of a pendulum. It is the same machine which we shall see by

and by

depicted in the tombs at Thebes; and the man is so evidently an ancient

Egyptian, that we find ourselves wondering how he escaped being

mummified four

or five thousand years ago.  THE SHADUF. By and

by,

a little breeze springs up. The men drop the rope and jump on board

– the big

sail is set – the breeze freshens – and away we go

again, as merrily as the day

we left Cairo. Towards sunset we see a strange object, like a giant

obelisk

broken off half-way, standing up on the western bank against an

orange-gold

sky. This is the pyramid of Meydûm, commonly called the false pyramid. It looks

quite near the bank; but this is an effect of powerful light and

shadow, for it

lies back at least four miles from the river. That night, having sailed

on till

past nine o’clock, we moor about a mile from Beni

Suêf, and learn with some

surprise that a man must be despatched to the governor of the town for

guards.

Not that anything ever happened to anybody at Beni Suêf, says

Talhamy; but that

the place is supposed not to have a first-rate reputation. If we have

guards,

we at all events make the governor responsible for our safety and the

safety of

our possessions. So the guards are sent for; and being posted on the

bank,

snore loudly all night long, just outside our windows. Meanwhile

the wind shifts round to the south, and next morning it blows full in

our

faces. The men, however, track up to Beni Suêf to a point

where the buildings

come down to the water’s edge and the towing-path ceases; and

there we lay-to

for awhile among a fleet of filthy native boats, close to the

landing-place. The

approach to Beni Suêf is rather pretty. The khedive has an

Italian-looking

villa here, which peeps up white and dazzling from the midst of a

thickly-wooded park. The town lies back a little from the river. A few

coffee-houses and a kind of promenade face the landing-place; and a

mosque

built to the verge of the bank stands out picturesquely against the

bend of the

river. And now

it

is our object to turn that corner, so as to get into a better position

for

starting when the wind drops. The current here runs deep and strong, so

that we

have both wind and water dead against us. Half our men clamber round

the corner

like cats, carrying the rope with them; the rest keep the dahabeeyah

off the

bank with punting poles. The rope strains – a pole breaks

– we struggle forward

a few feet, and can get no farther. Then the men rest awhile; try

again; and

are again defeated. So the fight goes on. The promenade and the windows

of the

mosque become gradually crowded with lookers-on. Some three or four

cloaked and

bearded men have chairs brought, and sit gravely smoking their

chibouques on

the bank above, enjoying the entertainment. Meanwhile the

water-carriers come

and go, filling their goat-skins at the landing-place; donkeys and

camels are

brought down to drink; girls in dark blue gowns and coarse black veils

come

with huge water-jars laid sidewise upon their heads, and, having filled

and

replaced them upright, walk away with stately steps, as if each

ponderous

vessel were a crown. So the

day

passes. Driven back again and again, but still resolute, our sailors,

by dint

of sheer doggedness, get us round the bad corner at last. The Bagstones

follows

suit a little later; and we both moor about a quarter of a mile above

the town.

Then follows a night of adventures. Again our guards sleep profoundly;

but the

bad characters of Beni Suêf are very wide awake. One

gentleman, actuated no

doubt by the friendliest motives, pays a midnight visit to the

Bagstones; but

being detected, chased, and fired at, escapes by jumping overboard. Our

turn

comes about two hours later, when the writer, happening to be awake,

hears a

man swim softly round the Philæ. To strike a light and

frighten everybody into

sudden activity is the work of a moment. The whole boat is instantly in

an

uproar. Lanterns are lighted on deck; a patrol of sailors is set;

Talhamy loads

his gun; and the thief slips away in the dark, like a fish. The

guards, of course, slept sweetly through it all. Honest fellows! They

were paid

a shilling a night to do it, and they had nothing on their minds. Having

lodged a formal complaint next morning against the inhabitants of the

town, we

received a visit from a sallow personage clad in a long black robe and

a

voluminous white turban. This was the chief of the guards. He smoked a

great

many pipes; drank numerous cups of coffee; listened to all we had to

say;

looked wise; and finally suggested that the number of our guards should

be

doubled. I

ventured

to object that if they slept unanimously, forty would not be of much

more use

than four. Whereupon he rose, drew himself to his full height, touched

his

beard, and said with a magnificent melodramatic air:–

“If they sleep, they

shall be bastinadoed till they die!” And now

our good luck seemed to have deserted us. For three days and nights the

adverse

wind continued to blow with such force that the men could not even

track

against it. Moored under that dreary bank, we saw our ten

days’ start melting

away, and could only make the best of our misfortunes. Happily the long

island

close by, and the banks on both sides of the river, were populous with

sand-grouse;

so Alfred went out daily with his faithful George and his unerring gun,

and

brought home game in abundance, while we took long walks, sketched

boats and

camels, and chaffered with native women for silver torques and

bracelets. These

torques (in Arabic Tók)

are tubular but massive, penannular, about as

thick as one’s little finger, and finished with a hook at one

end and a twisted

loop at the other. The girls would sometimes put their veils aside and

make a

show of bargaining; but more frequently, after standing for a moment

with great

wondering black velvety eyes staring shyly into ours, they would take

fright

like a troop of startled deer, and vanish with shrill cries, half of

laughter,

half of terror. At Beni

Suêf we encountered our first sand-storm. It came down the

river about noon,

showing like a yellow fog on the horizon, and rolling rapidly before

the wind.

It tore the river into angry waves, and blotted out the landscape as it

came.

The distant hills disappeared first; then the palms beyond the island;

then the

boats close by. Another second, and the air was full of sand. The whole

surface

of the plain seemed in motion. The banks rippled. The yellow dust

poured down

through every rift and cleft in hundreds of tiny cataracts. But it was

a sight not

to be looked upon with impunity. Hair, eyes, mouth, ears, were

instantly

filled, and we were driven to take refuge in the saloon. Here, although

every

window and door had been shut before the storm came, the sand found its

way in

clouds. Books, papers, carpets, were covered with it; and it settled

again as

fast as it was cleared away. This lasted just one hour, and was

followed by a

burst of heavy rain; after which the sky cleared and we had a lovely

afternoon.

From this time forth, we saw no more rain in Egypt. At

length,

on the morning of the fourth day after our first appearance at Beni

Suêf and

the seventh since leaving Cairo, the wind veered round again to the

north, and

we once more got under way. It was delightful to see the big sail again

towering up overhead, and to hear the swish of the water under the

cabin

windows; but we were still one hundred and nine miles from Rhoda, and

we knew

that nothing but an extraordinary run of luck could possibly get us

there by

the twenty-third of the month, with time to see Beni Hassan on the way.

Meanwhile, however, we make fair progress, mooring at sunset when the

wind

falls, about three miles north of Bibbeh. Next day, by help of the same

light

breeze which again springs up a little after dawn, we go at a good pace

between

flat banks fringed here and there with palms, and studded with villages

more or

less picturesque. There is not much to see, and yet one never wants for

amusement. Now we pass an island of sand-bank covered with snow-white

paddy-birds, which rise tumultuously at our approach. Next comes Bibbeh

perched

high along the edge of the precipitous bank, its odd-looking Coptic convent

roofed all over with little mud domes, like a cluster of earth-bubbles.

By and

by we pass a deserted sugar-factory, with shattered windows and a huge,

gaunt,

blackened chimney, worth of Birmingham or Sheffield. And now we catch a

glimpse

of the railway, and hear the last scream of a departing engine. At

night, we

moor within sight of the factory chimneys and hydraulic tubes of

Magagha, and

next day get on nearly to Golosanèh, which is the last

station-town before

Minieh. It is

now

only too clear that we must give up all thought of pushing on to Beni

Hassan

before the rest of the party shall come on board. We have reached the

evening

of our ninth day; we are still forty-eight miles from Rhoda; and

another

adverse wind might again delay us indefinitely on the way. All risks

taken into

account, we decide to put off our meeting till the twenty-fourth, and

transfer

the appointment to Minieh; thus giving ourselves time to track all the

way in

case of need. So an Arabic telegram is concocted, and our fleetest

runner

starts off with it to Golosanèh before the office closes for

the night. The

breeze, however, does not fail, but comes back next morning with the

dawn.

Having passed Golosanèh, we come to a wide reach in the

river, at which point

we are honoured by a visit from a Moslem santon of peculiar sanctity,

named

“Holy Sheik Cotton.” Now Holy Sheik Cotton, who

is a well-fed, healthy-looking

young man of about thirty, makes his first appearance swimming, with

his

garments twisted into a huge turban on the top of his head, and only

his chin

above water. Having made his toilet in the small boat, he presents

himself on

deck, and receives an enthusiastic welcome. Reïs Hassan hugs

him – the pilot

kisses him – the sailors come up one by one, bringing little

tributes of

tobacco and piastres which he accepts with the air of a Pope receiving

Peter’s pence. All dripping as he is, and smiling like an affable Triton, he

next

proceeds to touch the tiller, the ropes, and the ends of the yards,

“in order,”

says Talhamy, “to make them holy;” and then, with

some kind of final charm or

muttered incantation, he plunges into the river again, and swims off to

repeat

the same performance on board the Bagstones. From

this

moment the prosperity of our voyage is assured. The captain goes about

with a

smile on his stern face, and the crew look as happy as if we had given

them a

guinea. For nothing can go wrong with a dahabeeyah that has been

“made holy” by

Holy Sheik Cotton. We are certain now to have favourable winds

– to pass the

Cataract without accident – to come back in health and

safety, as we set out.

But what, it may be asked, has Holy Sheik Cotton done to make his

blessing so

efficacious? He gets money in plenty; he fasts no oftener than other

Mohammedans; he has two wives; he never does a stroke of work; and he

looks the

picture of sleek prosperity. Yet he is a saint of the first water; and

when he dies,

miracles will be performed at his tomb, and his eldest son will succeed

him in

the business. We had

the

pleasure of becoming acquainted with a good many saints in the course

of our

Eastern travels; but I do not know that we ever found they had done

anything to

merit the position. One very horrible old man named Sheik Saleem has,

it is

true, been sitting on a dirt heap near Farshût, unclothed,

unwashed, unshaven,

for the last half-century or more, never even lifting his hand to his

mouth to

feed himself; but Sheik Cotton had gone to no such pious lengths, and

was not

even dirty. We are

by

this time drawing towards a range of yellow cliffs that have long been

visible

on the horizon, and which figure in the maps as Gebel et

Tâyr. The Arabian

desert has been closing up on the eastern bank for some time past, and

now

rolls on in undulating drifts to the water’s edge. Yellow

boulders crop out

here and there above the mounded sand, which looks as if it might cover

many a

forgotten temple. Presently the clay bank is gone, and a low barrier of

limestone rock, black and shiny next the water-line, has taken its

place. And

now, a long way ahead, where the river bends and the level cliffs lead

on into

the far distance, a little brown speck is pointed out as the Convent of

the

Pulley. Perched on the brink of the precipice, it looks no bigger than

an

ant-heap. We had heard much of the fine view to be seen from the

platform on

which this Convent is built, and it had originally entered into our

programme

as a place to be visited on the way. But Minieh has to be gained now at

all

costs; so this project has to be abandoned with a sigh. And now

the rocky barrier rises higher, quarried here and there in dazzling

gaps of

snow-white cuttings. And now the convent shows clearer; and the cliffs

become

loftier; and the bend in the river is reached; and a long perspective

of

flat-topped precipice stretches away into the dim distance. It is a

day of saints and swimmers. As the dahabeeyah approaches, a brown poll

is seen

bobbing up and down in the water a few hundred yards ahead. Then one,

two,

three bronze figures dash down a steep ravine below the convent walls,

and

plunge into the river – a shrill chorus of voices, growing

momentarily more

audible, is borne upon the wind – and in a few minutes the

boat is beset by a

shoal of mendicant monks vociferating with all their might “Ana

Christian ya

Hawadji! – Ana Christian ya Hawadji!”

(I am a Christian, oh traveller!) As

these are only Coptic monks and not Moslem santons, the sailors, half

in rough

play, half in earnest, drive them off with punting poles; and only one

shivering, streaming object, wrapped in a borrowed blanket, is allowed

to come

on board. He is a fine shapely man, aged about forty, with splendid

eyes and

teeth, a well-formed head, a skin the colour of a copper beech-leaf,

and a face

expressive of such ignorance, timidity, and half-savage watchfulness as

makes

one’s heart ache. And this

is a Copt; a descendant of the true Egyptian stock; one of those whose

remote

ancestors exchanged the worship of the old gods for Christianity under

the rule

of Theodosius some fifteen hundred years ago, and whose blood is

supposed to be

purer of Mohammedan intermixture than any in Egypt. Remembering these

things,

it is impossible to look at him without a feeling of profound interest.

It may

be only fancy, yet I think I see in him a different type to that of the

Arab –

a something, however slight, which recalls the sculptured figures in

the tomb

of Ti. But

while

we are thinking about his magnificent pedigree, our poor

Copt’s teeth are

chattering piteously. So we give him a shilling or two for the sake of

all he

represents in the history of the world; and with these, and the

donation of an

empty bottle, he swims away contented, crying again and

again:– “Ketther-kháyrak

Sitt´t! Ketther-kháyrak keteer!”

(“Thank you, ladies! thank you much!”) And now

the convent with its clustered domes is passed and left behind. The

rock here

is of the same rich tawny hue as at Turra, and the horizontal strata of

which

it is composed have evidently been deposited by water. That the Nile

must at

some remote time have flowed here in an immensely higher level seems

also

probable; for the whole face of the range is honeycombed and water-worn

for

miles in succession. Seeing how these fantastic forms –

arched, and clustered,

and pendent – resemble the recessed ornamentation of

Saracenic buildings, I

could not help wondering whether some early Arab architect might not

once upon

a time have taken a hint from some such rocks as these. Thus the

day wanes, and the level cliffs keep with us all the way –

now breaking into

little lateral valleys and culs-de-sac

in which nestle clusters of tiny

huts and green patches of lupin; now plunging sheer down into the

river; now

receding inland and leaving space for a belt of cultivated soil and a

fringe of

feathery palms. By and by comes the sunset, when every cast shadow in

the

recesses of the cliffs turns to pure violet; and the face of the rock

glows

with a ruddier gold; and the palms on the western bank stand up in

solid bronze

against a crimson horizon. Then the sun dips, and instantly the whole

range of

cliffs turns to a dead, greenish grey, while the sky above and behind

them is

as suddenly suffused with pink. When this effect has lasted for

something like

eight minutes, a vast arch of deep blue shade, about as large in

diameter as a

rainbow, creeps slowly up the eastern horizon, and remains distinctly

visible

as long as the pink flush against which it is defined yet lingers in

the sky.

Finally the flush fades out; the blue becomes uniform; the stars begin

to show;

and only a broad glow in the west marks which way the sun went down.

About a

quarter of an hour later comes the after-glow, when for a few minutes

the sky

is filled with a soft, magical light, and the twilight gloom lies warm

upon the

landscape. When this goes, it is night; but still one long beam of

light

streams up in the tracks of the sun, and remains visible for more than

two

hours after the darkness has closed in. Such is

the sunset we see this evening as we approach Minieh; and such is the

sunset we

are destined to see with scarcely a shade of difference at the same

hour and

under precisely the same conditions for many a month to come. It is

very

beautiful, very tranquil, full of wonderful light and most subtle

gradations of

tone, and attended by certain phenomena of which I shall have more to

say

presently; but it lacks the variety and gorgeousness of our northern

skies.

Nor, given the dry atmosphere of Egypt, can it be otherwise. Those who

go up

the Nile expecting, as I did, to see magnificent Turneresque pageants

of

purple, and flame-colour, and gold, will be disappointed as I was. For

your

Turneresque pageant cannot be achieved without such accessories of

cloud and

vapour as in Nubia are wholly unknown, and in Egypt are of the rarest

occurence. Once, and only once, in the course of an unusually

protracted

sojourn on the river, had we the good fortune to witness a grand

display of the

kind; and then we had been nearly three months in the dahabeeyah. Meanwhile,

however, we never weary of these stainless skies, but find in them,

evening

after evening, fresh depths of beauty and repose. As for that strange

transfer

of colour from the mountains to the sky, we had repeatedly observed it

while

travelling in the Dolomites the year before, and had always found it

take

place, as now, at the moment of the sun’s first

disappearance. But what of this

mighty after-shadow, climbing half the heavens and bringing night with

it? Can

it be the rising shadow of the world projected on the one horizon as

the sun

sinks on the other? I leave the problem for wiser travellers to solve.

We have

not science enough amongst us to account for it. That

same

evening, just as the twilight came on, we saw another wonder

– the new moon on

the first night of her first quarter; a perfect orb, dusky, distinct,

and

outlined all round with a thread of light no thicker than a hair.

Nothing could

be more brilliant than this tiny rim of flashing silver; while every

detail of

the softly glowing globe within its compass was clearly visible. Tycho

with its

vast crater showed like a volcano on a raised map; and near the edge of

the

moon’s surface, where the light and shadow met, keen sparkles

of

mountain-summits catching the light and relieved against the dusk, were

to be

seen by the naked eye. Two or three evenings later, however, when the

silver

ring was changed to a broad crescent, the unilluminated part was as it

were

extinguished, and could no longer be discerned even by help of a glass.

The wind

having failed as usual at sunset, the crew set to work with a will and

punted

the rest of the way, so bringing us to Minieh about nine that night.

Next

morning we found ourselves moored close under the khedive’s

summer palace – so

close that one could have tossed a pebble against the lattice windows

of his

Highness’s hareem. A fat gate-keeper sat outside in the sun,

smoking his

morning chibouque and gossiping with the passers-by. A narrow promenade

scantily planted with sycamore figs ran between the palace and the

river. A

steamer or two, and a crowd of native boats, lay moored under the bank;

and

yonder, at the farther end of the promenade, a minaret and a cluster of

whitewashed houses showed which way one must turn in going to the town.

It

chanced

to be market-day; so we saw Minieh under its best aspect, than which

nothing

could well be more squalid, dreary, and depressing. It was like a town

dropped

unexpectedly into the midst of a ploughed field; the streets being mere

trodden

lanes of mud dust, and the houses a succession of windowless mud

prisons with

their backs to the thoroughfare. The Bazaar, which consists of two or

three

lanes a little wider than the rest, is roofed over here and there with

rotting

palm-rafters and bits of tattered matting; while the market is held in

a space

of waste ground outside the town. The former, with its little

cupboard-like

shops in which the merchants sit cross-legged like shabby old idols in

shabby

old shrines – the ill-furnished shelves – the

familiar Manchester goods – the

gaudy native stuffs – the old red saddles and faded rugs

hanging up for sale –

the smart Greek stores where Bass’s ale, claret,

curaçoa, Cyprus, Vermouth,

cheese, pickles, sardines, Worcester sauce, blacking, biscuits,

preserved

meats, candles, cigars, matches, sugar, salt, stationery, fireworks,

jams, and

patent medicines can all be bought at one fell swoop – the

native cook’s shop

exhaling savoury perfumes of Kebabs and lentil soup, and presided over

by an

Abyssinian Soyer blacker than the blackest historical personage ever

was

painted – the surging, elbowing, clamorous crowd –

the donkeys, the camels, the

street-cries, the chatter, the dust, the flies, the fleas, and the

dogs, all

put us in mind of the poorer quarters of Cairo. In the market, it is

even

worse. Here are hundreds of country folk sitting on the ground behind

their

baskets of fruits and vegetables. Some have eggs, butter, and

buffalo-cream for

sale, while others sell sugar-canes, limes, cabbages, tobacco, barley,

dried

lentils, split beans, maize, wheat, and dura. The women go to and fro

with

bouquets of live poultry. The chickens scream; the sellers rave; the

buyers

bargain at the top of their voices; the dust flies in clouds; the sun

pours

down floods of light and heat; you can scarcely hear yourself speak;

and the

crowd is as dense as that other crowd which at this very moment, on

this very

Christmas Eve, is circulating among the alleys of Leadenhall Market. The

things

were very cheap. A hundred eggs cost about fourteen-pence in English

money;

chickens sold for fivepence each; pigeons from twopence to

twopence-halfpenny;

and fine live geese for two shillings a head. The turkeys, however,

which were

large and excellent, were priced as high as three-and-sixpence; being

about

half as much as one pays in Middle and Upper Egypt for a lamb. A good

sheep may

be bought for sixteen shillings or a pound. The M. B.’s, who

had no dragoman

and did their own marketing, were very busy here, laying in store of

fresh

provision, bargaining fluently in Arabic, and escorted by a bodyguard

of

sailors. A

solitary

dôm palm, the northernmost of its race and the first specimen

one meets with on

the Nile, grows in a garden adjoining this market-place; but we could

scarcely

see it for the blinding dust. Now a dôm palm is just the sort

of tree that De

Wint should have painted – odd, angular, with long forked

stems, each of which

terminates in a shock-headed crown of stiff finger-like fronds shading

heavy

clusters of big shiny nuts about the size of Jerusalem artichokes. It

is, I

suppose, the only nut in the world of which one throws away the kernel

and eats

the shell; but the kernel is as hard as marble, while the shell is

fibrous, and

tastes like stale ginger-bread. The dôm palm must bifurcate,

for bifurcation is

the law of its being; but I could never discover whether there was any

fixed

limit to the number of stems into which it might subdivide. At the same

time, I

do not remember to have seen any with less than two heads or more than

six. Coming

back through the town, we were accosted by a withered one-eyed hag like

a

re-animated mummy, who offered to tell us our fortunes. Before her lay

a dirty

rag of handkerchief full of shells, pebbles, and chips of broken glass

and

pottery. Squatting toad-like under a sunny bit of wall, the lower part

of her

face closely veiled, her skinny arms covered with blue and green glass

bracelets and her fingers with misshapen silver rings, she hung over

these

treasures; shook, mixed, and interrogated them with all the fervour of

divination; and delivered a string of the prophecies usually

forthcoming on

these occasions. “You

have

a friend far away, and your friend is thinking of you. There is good

fortune in

store for you; and money is coming to you; and pleasant news on the

way. You

will soon receive letters in which there will be something to vex you,

but more

to make you glad. Within thirty days you will unexpectedly meet one

whom you

dearly love,” etc. etc. etc. It was

just the old familiar story retold in Arabic, without even such

variations as

might have been expected from the lips of an old fellâha born

and bred in a

provincial town of Middle Egypt. It may

be

that opthalmia especially prevailed in this part of the country, or

that being

brought unexpectedly into the midst of a large crowd, one observed the

people

more narrowly, but I certainly never saw so many one-eyed human beings

as that

morning at Minieh. There must have been present in the streets and

market-place

from ten to twelve thousand natives of all ages, and I believe it is

not

exaggeration to say that at least every twentieth person, down to

little

toddling children of three and four years of age, was blind of an eye.

Not

being a particularly well-favoured race, this defect added the last

touch of

repulsiveness to faces already sullen, ignorant, and unfriendly. A more

unprepossessing population I would never wish to see – the

men half stealthy,

half insolent; the women bold and fierce; the children filthy, sickly,

stunted,

and stolid. Nothing in provincial Egypt is so painful to witness as the

neglected condition of very young children. Those belonging to even the

better

class are for the most part shabbily clothed and of more than doubtful

cleanliness; while the offspring of the very poor are simply encrusted

with

dirt and sores, and swarming with vermin. It is at first hard to

believe that

the parents of these unfortunate babies err, not from cruelty, but

through

sheer ignorance and superstition. Yet so it is; and the time when these

people

can be brought to comprehend the most elementary principles of sanitary

reform

is yet far distant. To wash young children is injurious to health;

therefore

the mothers suffer them to fall into a state of personal uncleanliness

which is

alone enough to engender disease. To brush away the flies that beset

their eyes

is impious; hence opthalmia and various kinds of blindness. I have seen

infants

lying in their mothers’ arms with six or eight flies in each

eye. I have seen

the little helpless hands put down reprovingly, if they approached the

seat of

annoyance. I have seen children of four and five years old with a large

fleshy

lump growing out where the pupil had been destroyed. Taking these

things into

account, the wonder is, after all, not that three children should die

in Egypt

out of every five – not that each twentieth person in certain

districts should

be blind, or partially blind; but that so many as forty per cent of the

whole

infant population should actually live to grow up, and that ninety-five

per

cent should enjoy the blessing of sight. For my own part, I had not

been many

weeks on the Nile before I began systematically to avoid going about

the native

towns whenever it was practicable to do so. That I may so have lost an

opportunity of now and then seeing more of the street-life of the

people is

very probable; but such outside glimpses are of little real value, and

I at all

events escaped the sight of much poverty, sickness, and squalor. The

condition

of the inhabitants is not worse, perhaps, in an Egyptian Beled3

than

in many an Irish village; but the condition of the children is so

distressing

that one would willingly go any number of miles out of the way rather

than

witness their suffering without the power to alleviate it.4

If the

population in and about Minieh are personally unattractive, their

appearance at

all events matches their reputation, which is as bad as that of their

neighbors. Of the manners and customs of Beni Suêf we had

already some

experience; while public opinion charges Minieh, Rhoda, and most of the

towns

and villages north of Siût, with the like marauding

propensities. As for the

villages at the foot of Beni Hassan, they have been mere dens of

thieves for

many generations; and though razed to the ground some years ago by way

of

punishment, are now rebuilt, and in as bad odour as ever. It is

necessary,

therefore, in all this part of the river, not only to hire guards at

night,

but, when the boat is moored, to keep a sharp look-out against thieves

by day.

In Upper Egypt it is very different. There the natives are

good-looking,

good-natured, gentle, and kindly; and though clever enough at

manufacturing and

selling modern antiquities, are not otherwise dishonest. That same evening – (it was Christmas Eve) – nearly two hours earlier than their train was supposed to be due, the rest of our party arrived at Minieh. ________________________1 Sorghum

vulgare. 2 The shâdûf

has been so well described by the Rev. F. B. Zincke, that I cannot do

better

than quote him verbatim:– “Mechanically, the shadoof is an application of the

lever. In no machine which the wit of man, aided by the accumulation of

science, has since invented, is the result produced so great in

proportion to

the degree of power employed. The lever of the shadoof is a long stout

pole poised

on a prop. The pole is at right angles to the river. A large lump of

clay from

the spot is appended to the inland end. To the river end is suspended a

goat-skin bucket. This is the whole apparatus. The man who is working

it stands

on the edge of the river. Before him is a hole full of water fed from

the

passing stream. When working the machine, he takes hold of the cord by

which

the empty bucket is suspended, and bending down, by the mere weight of

his

shoulders dips it in the water. His effort to rise gives the bucket

full of

water an upward cant, which, with the aid of the equipoising lump of

clay at

the other end of the pole, lifts it to a trough into which, as it tilts

on one

side, it empties its contents. What he has done has raised the water

six or seven

feet above the level of the river. But if the river has subsided twelve

or

fourteen feet, it will require another shadoof to be worked in the

trough into

which the water of the first has been brought. If the river has sunk

still

more, a third will be required before it can be lifted to the top of

the bank,

so as to enable it to flow off to the fields that require

irrigation.” – "Egypt

of the Pharoahs and the Khedive,"

p. 445 et seq.

3 Beled

–

village. 4 Miss Whately, whose evidence on this subject is peculiarly valuable, states that the majority of native children die off at, or under, two years of age ("Among the Huts," p. 29); while M. About, who enjoyed unusual opportunities of inquiring into facts connected with the population and resources of the country, says that the nation loses three children out of every five. “L’ignorance publique, l’oubli des premiers éléments d’hygiène, la mauvaise alimentation, l’absence presque totale des soins médicaux, tarissent la nation dans sa source. Un peuple qui perd régulièrement trois enfants sur cinq ne saurait croître sans miracle.” – "Le Fellah," p. 165. |