| 8

The Merchant

Service

(a) HISTORY AND

DEVELOPMENT OF STEAM NAVIGATION

FROM the early

experiments of Watt, Fitch, Miller, Symmington, Bell and Fulton, the

development of the steamship was but gradual, and the first attempts at

navigating anything but inland waters were not at all successful.

Not until 1819 was

the trans-Atlantic steam voyage accomplished, and that by the paddle-steamer

Savannah, which sailed from Savannah (Georgia) for St. Petersburg via Great

Britain. This was the first true ocean steamship. She was of 350 tons burthen,

and was built, sparred and fitted with steam machinery at Corlear's Hook, New

York. Hence under Captain Moses Rogers she sailed to Savannah, making the

voyage in seven days.

The ship was full

rigged, and not necessarily dependent upon her wrought iron paddles, which

could be taken aboard at will. Her engine, direct acting, low pressure, had a

forty-inch cylinder and a six-foot stroke of piston. Her fuel was pine wood,

which, of course, could only be replenished as convenience served. When she

sailed for Liverpool thousands waved her God-speed with the deepest misgivings

as to the result of this novel marriage of sail and steam.

Steaming and

sailing, the Savannah made port

in twenty-five days, having had recourse to the use of her canvas, exclusively,

for more than a third of the time. From Liverpool her prow was turned toward

the Baltic, and touching at Stockholm, Copenhagen and other ports, she ended

her voyage at St. Petersburg, afterwards returning to America, where her

engines and boilers were taken out, and she was converted into a sailing

packet.

The experiment was

again followed on a large scale in 1825 by the fitting out in America of the Enterprise, for a voyage to India. By

sailing or steaming alternately, as the weather and her fuel permitted, she

arrived in the Hoogley in forty-seven days.

Although the Savannah and the Enterprise succeeded through favourable

circumstances in making long voyages, they were essentially sailing ships, and

their steam power was merely an accessory. The Great

Western and the Sirius

in the year 1838 first really demonstrated that it was practical to navigate a

steamship without the unfurling of a yard of canvas; and the importance of the

traffic which was thus inaugurated on the Atlantic was a vital and immediate

factor in fostering its further development.

The Sirius, 178 feet in length by 251 feet

beam and 18f feet in depth, was dispatched from Queenstown for New York by the

British and American Steam Navigation Company on April 5, 1838, and arrived in

New York on April 21, having been something over sixteen days upon the passage,

during which she maintained an average speed of 81 knots per hour, on a

consumption of 24 tons of coal per day.

A few hours after

the arrival of the Sirius in New York Harbour there also arrived the Great Western, which left the Bristol

Channel three days later than the Sirius.

The arrival of

these two boats set the City of New York ablaze with excitement, some idea of

which can be gained from the account printed by the Evening Post (N.Y.) on the following day.

"The arrival

yesterday of the steam-packets Sirius

and Great Western caused in this

city that stir of eager curiosity and speculation which every new enterprise of

any magnitude awakens in this excitable community. The Battery was thronged

yesterday morning with thousands of persons of both sexes to look on the Sirius, which had crossed the Atlantic by

the power of steam, as she lay anchored near at hand, gracefully shaped,

painted black all over, the water around her covered with boats filled with

people passing and repassing, some conveying and some bringing back those who

desired to go aboard.

"When the Great Western at a later hour was seen

ploughing her way through the waters towards the city the crowd became more

numerous, and the whole bay to a great distance was dotted with boats, as if

everything that could be manned by oars had left its place at the wharves. It

would seem, in fact, a kind of triumphal entry.

"The

practicability of establishing a regular intercourse between Europe and America

is considered to be solved by the arrivals of these vessels, notwithstanding

the calculations of certain ingenious men, at the head of whom is a Dr. Lardner,

who have proved by figures that the thing is impossible, and declared that

ships would perforce be obliged to replenish their bunkers at either the Azores

or Newfoundland in order to be able to complete the voyage; stating further

that 'the whole project was chimerical in the extreme, and that one might as

well talk of making a voyage to the moon.' The only question which now remains

is whether the greater regularity and speed with which the passage is effected

in steam vessels will compensate for the additional cost, or whether, in fact,

on balancing all considerations, any additional cost will be incurred."

The Great Western continued in the

trans-Atlantic trade for about six years, during which time she made 70 voyages

across the ocean, averaging 15½ days westward and 131 days eastward. The

quickest passage to New York was made in 12 days and 19 hours, and the quickest

passage to Liverpool in 12 days and 7 hours.

From this date and

from these beginnings were developed the trans-Atlantic steamship lines of the

present day.

Among other earlier

ships engaged in this trade were the Royal

William, the British Queen,

the President, the Liverpool and the Great Britain.

The Cunard Line was

established in 1840 with a fleet of four ships, the Britannia, the Acadia,

the Columbia and Caledonia, each with an average

horse-power of 440.

William Fairbairn,

of Manchester, England, built three small iron steamers in 1831, and afterwards

became associated with the Lairds, of Birkenhead, when the latter went largely

into this construction. Up to 1848 they had built more than 100 iron vessels.

But not till 1855

was a great ocean steamship, the Cunarder Persia,

built of this material on well-formulated and scientific principles. In France

and the United States iron had only been used for the structural framework.

The Persia was the turning point in a new

movement. She was 360 feet long, 45 feet in breadth and 35 feet in depth, with

a capacity of 1,200 tons greater than the largest of her sisters. In addition

to this great increase of strength, ships wholly constructed of iron or steel

are lighter than those of the same tonnage made of wood, and can carry larger

freights. As they can be enlarged beyond the dimensions that limit wooden

ships, they profit by the law that the larger the capacity, the less

proportionate space need be devoted to the stowage of fuel, their cargo room

being thus increased. This substitution of steel for iron was almost as great

an advance as that of iron for oak.

A still more

important invention was at this time fast establishing its supremacy. It had

long been seen that the paddle-wheel even at its best did not by any means

fulfil all requirements, and even during its best days the screw propeller had

come into partial use as an auxiliary. It had been observed, for instance, that

as the latter's blades work in the current following the ship, the tendency of

its action was to restore its static condition to the agitated fluid, taking

up and restoring usefully a large part of the energy which would, by reason of

friction, otherwise have been lost. The screw, too, through its complete

submersion, is more continuously efficient than the paddle-wheel, which is

only partially submerged at any time, and for some periods (as in a rolling

sea) perhaps not at all. The rapid and smooth rotation of the screw permits the

use of light, fast-running, quick-acting engines, economizes weight and space,

and increases cargo room. The economy of steam in a quick-running engine,

especially in one of the compound type, also means less expense of fuel, and a

saving in stowage and carriage.

The history of the

adoption of the screw propeller is full of romantic interest. The honours

already won by the Cunard were challenged about ten years later by an American

Company, the Collins' Line, which, however, unfortunately came to grief in the

course of a few years. The first really dangerous competitors of the Cunard

were the vessels of the Inman Line, a company which had experimentally adopted

the principle of the screw propeller, which was destined eventually to

supersede the paddle-wheel principle, upon which the Cunard Company had up to

that time relied. In fact, for some years later the Cunard Company still

continued to construct paddle-steamers, the Scotia,

which was one of the last and finest vessels of this class, reaching a capacity

of 3,870 tons. Not long after the building of the Scotia, however, the Cunard Company, spurred probably by the

competition of the Inman Line, wrung from the Government of the day permission

to fit their steamers with screw propellers for the carriage of the mails. The

first Cunarder of this new type was called the China, and it was her success,

with that of her sister boats, that finally established the superiority of the

screw.

The victory of this

principle (of the screw propeller) was one of the great turning-points in the

history of steam navigation, and from the day of its adoption by the Cunard the

progressive development of the steamship on modern lines may be dated.

Following the example of these two famous pioneer lines came the establishment

of the "P. & O." Company (at first known as the Peninsular

Company), in 1837; the Royal Mail, in 1839; the Pacific Steam Navigation

Company, in 1847; the "B. I.," in 1855; the Anchor Line, in 1856; the

German Nord Deutscher Lloyd, in

1858; the French Compagnie Transatlantique,

in 1861; the building of the Britannic

and the Germanic (of the

"White Star" line), in 1874; the establishment of the Orient Line (to

Australia), in 1877; and the first direct steamship service to New Zealand, in

1883.

The year 1888 and

the next following decade saw the introduction of the "twin-screw"

principle in the construction of the famous City

of New York and City of Paris

(Inman Line); the Majestic and

the Teutonic (White Star Line); the Lucania

and Campania (Cunard); and the Celtic (White Star), the last-mentioned in

1903. The most recent development of steam navigation has been the introduction

of engines on the turbine principle, but this new principle at the time of

writing (January, 1903) can hardly be said to be yet established, as it is only

within the present year that turbine steamers have been introduced (into the

cross-channel service).

It is impossible

(even in the merest sketch of steamboat development) to conclude without making

some reference to what is generally known as the "American Shipping

Combine," or "Trust," of 1902 — a gigantic enterprise, the

ultimate effect of which upon the shipping trade generally cannot at present be

foreseen. The facts, however, are that this new "mammoth" Company has

started with a gross capital of £24,000,000, and has bought up the "White

Star," the Leyland, tho Dominion and the British and North Atlantic

Companies; and that the British Government, in return, has subsidised the

Cunard.

Briefly summarising

various stages in the evolution of the ocean liner since the days of the

Savannah, we find that the factors of its progress have been developed in the

following order: —

(1) Substitution of

the steam-engine for canvas, as the main motive-power.

(2) The

substitution of iron for wood in the construction of the hull, and later that

of steel for iron, and the consequent development, to the best advantage, of

the long, sharp, yacht-like lines which have given increased room, size and

speed.

(3) The adoption of

the screw propeller as a means of propulsion in place of the less effective and

more cumbersome paddle-wheel.

(4) The adoption of

the compound triple and quadruple engine, with surface condenser, which makes

it possible to utilise the steam more than once before its final discharge into

the condenser, an enormous economy of fuel and a greater speed and space for

the accommodation of passengers and freight being thus secured.

It has hitherto

been found that each decade has been distinguished by some radical improvement

in steamer construction from the decade which preceded it. The accompanying

table shows this progress (approximately), and at the same time exhibits the

most important approximate rises in boiler pressure, and the approximate

improvement in engine power.

Decade

|

Development in

construction

|

Approximate

boiler pressure

|

Approximate

lb. of coal

per h.p.

|

|

1845-'55

|

Iron in place of wood

|

10 to 20

|

4.5 to 3.5

|

|

1855-'65

|

Screw in place of paddle-wheel

|

20 to 35

|

3.5 to 2.9

|

|

1865-'75

|

Compound in place of simple engines

|

35 to 60

|

2.9 to 2.2

|

|

1875-'85

|

Steel in place of iron, and triple expansion engines

|

60 to 125

|

2.2 to 1.9

|

|

'85-1900

|

Twin screws, quadruple expansion and forced draught

|

125 to 200

|

1.9 to 1.3

|

It is interesting to note the vast stores of food that

are used on an Atlantic liner. During a single trans-Atlantic trip on an

average liner there were used — Fresh beef, 15,000 lbs.; fresh mutton, 2,500

lbs.; fowls, 650 head; game, 350 head; cabbages, 250 head; turnips, 160

bunches; leeks, 60 bunches; onions, 4,480 lbs.; potatoes, 17,920 lbs.; parsley,

50 bushels; tomatoes, 200 lbs.; rhubarb, 130 bunches; asparagus, 30 tins; green

corn, 80 tins; peas, 140 tins; tomatoes, 70 tins; canned meats, 60 tins; flour,

30 barrels; sugar, 1,600 lbs.; coffee, 350 lbs.; tea, 136 lbs.; as well as 16

tons of ice, 5,000 eggs, 2,000 lbs. of butter, 400 quarts of ice cream, 20

barrels of oysters in the shell, 700 gallons of milk, 5,000 lbs. of fish, a

large quantity of fruit, and many other things. Of the wines, liquors, etc. —

champagne, 200 pints; claret, 220 pints; whiskey, 170 bottles; liquors, 14

bottles; beer and porter, 240 dozen bottles; mineral waters, 350 dozen bottles;

cigars, 1,100; cigarettes, 160 packages; tobacco, 100 lbs.; water, 140 tons.

In the

refrigerating rooms are stored several hundred tons of ice, all of it in such a

way that it may be obtained at a moment's notice, and yet so closely packed

that there is no space lost.

There is seldom a

scarcity of drinking-water on board passenger steamships. There are large tanks

of a capacity of five hundred or six hundred tons on nearly all the large

steamships, and all carry a condenser, which makes it possible to have fresh

water directly from the ocean. Salt water, however, is only used for the baths

as a rule.

The amount of food

that can be cooked in the various galleys is enormous, the cooks, of whom there

is a host, often preparing three or more meals a day for 1,000 to 2,000 people,

on the largest of the passenger ships.

(b) MERCHANT

VESSELS LAUNCHED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

DURING RECENT YEARS*

|

Year

|

|

|

STEAM

|

SAIL

|

TOTAL

|

|

NO.

|

Gross

Tonnage

|

NO.

|

Gross

Tonnage

|

NO.

|

Gross

Tonnage

|

|

1888

|

458

|

757,081

|

81

|

80,959

|

539

|

838,040

|

|

1889

|

595

|

1,083,793

|

95

|

125,568

|

690

|

1,209,361

|

|

1890

|

651

|

1,061,619

|

92

|

133,086

|

743

|

1,194,705

|

|

1891

|

641

|

878,353

|

181

|

252,463

|

822

|

1,130,816

|

|

1892

|

512

|

841,356

|

169

|

268,594

|

681

|

1,109,950

|

|

1893

|

438

|

718,277

|

98

|

118,106

|

536

|

836,383

|

|

1894

|

549

|

964,926

|

65

|

81,582

|

614

|

1,046,508

|

|

1895

|

526

|

904,991

|

53

|

45,976

|

579

|

950,967

|

|

1896

|

628

|

1,113,831

|

68

|

45,920

|

696

|

1,159,751

|

|

1897

|

545

|

924,382

|

46

|

28,104

|

591

|

952,486

|

|

1898

|

744

|

1,363,318

|

17

|

4,252

|

761

|

1,367,570

|

|

1899

|

714

|

1,414,774

|

12

|

2,017

|

726

|

1,416,791

|

|

1900

|

664

|

1,432,600

|

28

|

9,871

|

692

|

1,442,471

|

|

1901

|

591

|

1,501,078

|

48

|

23,661

|

639

|

1,524,739

|

[*By kind

permission, from Lloyd's Calendar.]

* Since writing the above a yet more gigantic cargo

steamer has been built in America, viz. the S.S. Minnesota, whose carrying capacity is just about double

even that of the Cedric and the Celtic.

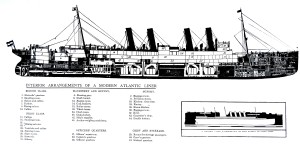

[CLICK ON THE IMAGE ABOVE TO SEE A FULL RENDERING OF THE

INTERIOR ARRANGEMENTS OF A MODERN STEAMSHIP CHART]

(c) THE LARGEST

STEAMSHIPS AFLOAT

Name

|

Line

|

Gross Tonnage

|

Length

|

Beam

|

Cedric *

Celtic *

Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Oceanic

Deutschland

Kron Prinz Wilhelm

Kaiser Wilhelm

der Grosse

Saxonia

Ivernia

Minneapolis

Minnehaha

Minnetonka

Pennsylvania

Campania

Lucania

Walmer Castle

Rijndam

Potsdam

Athenic

Noordam

Kaiser Frederick

Blucher

Moltke

Carpathia

Kroonland

Finland

Haverford

Merion

St. Paul

St. Louis

New England

Korea

Siberia

La Savoie

La Lorraine

Tunisian

Bavarian

Briton

Mongolia

Moldavia

Majestic

Teutonic

Kildonan Castle

Orontes

|

White Star

White Star

N.D.L.

White Star .

Hamb. Am.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

Cunard

Cunard

Atl. Trnspt.

Atl, Trnspt.

Atl, Trnspt.

Hamb. Am.

Cunard

Cunard

Union-Castle

Holland Am.

Holland Am.

White Star

Holland Am.

N.D.L.

Hamb. Am.

Hamb. Am.

Cunard

Red Star

Red Star

American

American

American

American

Dominion

Hamb. Am.

Hamb. Am.

Cie. Gen.

Trans. Atl.

Cie. Gen.

Trans. Atl.

Allan

Allan

Union-Castle

P. and O.

P. and O.

White Star

White Star

Union-Castle

Orient

|

21,000

20,880

19,500

17,274

15,500

15,000

14,000

13,963

13,800

13,402

13,402

13,400

13,333

13,000

12,950

12,570

12,500

12,500

12,500

12,500

12,480

12,372

12,372

12,000

12,000

12,000

11,635

11,635

11,629

11,629

11,406

11,300

11,300

11,200

11,200

10,576

10,576

10,248

10,000

10,000

9,965

9,965

9,664

9,000

|

700

700

706.5

705.5

686

633.5

649

600

600

600.7

600.7

600

559.4

625

625

565

565

520

565

581

580

580

530

530

535

535

550

563

563

500.6

500

530

582

582

515

|

75

75

68

67

66

64

64

65

65

65

62

65

64

62

62

62

63

60

60

59

59

63

63

59

60

60

59

59

60

57

57

59

|

(d)

TONNAGE OF THE LARGEST STEAMSHIP COMPANIES.

Numerical Order

|

Name of Company

|

No.

of

Ships

|

Tons

|

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

|

Hamburg American

Nord Deutscher Lloyd

Elder, Dempster and Company

British India S. N. Company

Peninsular and Oriental Company

Messageries Maritimes

F. Leyland and Company

Union-Castle Line

Nippon Yusen Kaisha

White Star Line

General S. N. Co. of Italy

Wilson Line

Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

Austrian Lloyd

American Line

Ocean Steamship Company

Clan Line

Hansa Line

Allan Line

Lamport and Holt

Harrison Line

Anchor Line

Maclay and Maclntyre

Cunard Line

Atlantic Transport Company

Dominion Line

Johnston Line

R. Ropner

Cia Transatlantica

Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

J. Westoll

Bucknall Brothers

Chargeurs Réunis

|

202

111

120

120

58

62

55

41

69

25

102

89

59

68

25

41

46

57

36

47

31

41

51

26

17

13

24

36

23

28

38

23

26

|

541,085

454,936

382,560

378,770

313,343

246,277

242,781

222,613

218,361

212,403

205,104

189,818

183,243

169,436

167,105

165,143

164,487

157,037

152,367

149,712

146,625

132,540

126,917

126,332

123,000

105,430

100,460

100,426

88,453

88,205

88,306

83,207

81,149

|

(e)

THE MERCHANT FLEETS OF THE CHIEF MARITIME POWERS

|

Country

|

Number

|

Tons

|

|

A. STEAMERS.

United Kingdom

Colonies

United States

Aust.-Hungarian

Belgian

Danish

Dutch

French

German

Italian

Japanese

Norwegian

Russian

Spanish

Swedish

B. SAILING

VESSELS.

United Kingdom

Colonies

United States

Danish

Dutch

French

German

Italian

Japanese

Norwegian

Russian

Spanish

Swedish

|

7,161

946

1,036

237

118

365

307

679

1,293

339

503

859

529

466

703

1,773

989

2,250

414

116

568

493

874

882

1,462

761

163

780

|

12,053,395

685,786

1,704,156

462,366

164,791

410,468

515,530

1,068,036

2,407,410

657,981

524,125

810,335

533,029

734,557

451,020

1,602,767

366,259

1,393,188

97,726

62,579

338,847

488,372

459,557

120,539

816,885

256,224

51,791

225,199

|

(f) PRINCIPAL

PASSENGER ROUTES FROM BRITISH PORTS

AMERICA. —

Halifax, Montreal and Quebec, via Liverpool; 8 to 10 days; £10 upwards.

New York. —

Via Liverpool; 7 to 10 days; via White Star and Cunard Lines; £12 upwards.

Via

Southampton; Nord Deutscher Lloyd, Hamburg-American and American Lines; £12

upwards; 7 to 10 days.

Via the

Thames; Atlantic Transport Line; 8 to 10 days; £10 upwards.

Boston. —

Via Liverpool; Cunard and Dominion Lines; 8 to 10 days; £10 upwards.

San

Francisco and Vancouver. — Via Montreal, New York and Boston, thence overland;

12 to 15 days; £26 upwards.

Philadelphia.

— From Liverpool, via Queenstown; 12 days; £7 7s.

New Orleans.

— Via Liverpool; 16 to 18 days; £16.

West Indies.

— Via Southampton or Bristol; 12 to 15 days; about £25.

Brazil and

River Plate. — Via Southampton; £22 to £35.

AUSTRALASIA.

— Melbourne, Sydney, Auckland — London or Southampton, via Suez Canal; about 6

weeks; £70.

From

Liverpool, via Cape, from £14 upwards.

BELGIUM. —

Ostend, from London direct; G.S.N. Co., 10 hours; 7s. 6d.

Antwerp. —

Via Hull or Harwich; 12 to 15 hours; £1 upwards.

Via Ostend;

8f hours; £1 18s.

CHINA. —

Shanghai, via Colombo, Straits and Hong Kong; about 6 weeks from Liverpool or

London; £70 upwards.

EGYPT. —

Cairo, via Alexandria or Port Said, from Liverpool or London; 8 to 12 days; £20

to £28.

FRANCE. —

Bordeaux, from Liverpool or London; 3 to 4 days; about £5.

Havre, via

Southampton, 9 hours.

Cherbourg,

via Southampton, 10 hours.

St. Malo,

via Southampton, 10 hours.

Dieppe, via

Newhaven, 3¼ hours.

Boulogne,

via Folkestone, 1½ to 1¾ hour.

— from London direct; 10 hours; 10s.; Bennett

SS. Co.

Calais, via

Dover, 1 to 4 hour.

Marseilles,

via Liverpool or London, 5 to 7 days; £10 upwards.

GERMANY. —

Hamburg, via Harwich, £1 17s. 6d. Bremen, from London; £1 15s.

GREECE. —

Athens, via Brindisi (Italy) or Marseilles; fares from London, £15 upwards.

HOLLAND. —

Amsterdam and Rotterdam, via Hook of Holland, from Harwich; 11 hours; £1 9s.

upwards.

Via

Flushing; 13 hours; £1 10s. upwards.

INDIA. —

Bombay, Calcutta and Colombo, from London or Liverpool; about 3 weeks; £50

upwards.

ITALY. —

Genoa, from Southampton; 5 to 7 days; £10 upwards.

Naples; 6 to

7 days; £12 upwards.

JAPAN. —

From London or Liverpool; 6 to 7 weeks; £60.

PALESTINE. —

Jerusalem, via Alexandria; 9 to 10 days; about £25.

RUSSIA. —

Odessa, steamer from Hull; about 14 days; about £12.

St.

Petersburg, via Hull; about 7 days; £5 5s.

SCANDINAVIA.

— Bergen, Christiania, Copenhagen, from Newcastle, London or Hull; l½ to 3

days; £3 to £6.

Gothenburg,

Stockholm, from London, Leith and Hull; £3 upwards.

SPAIN. —

Gibraltar, via London or Liverpool; 4 to 6 days; £8 to £10.

TURKEY. —

Constantinople, from Liverpool; 10 to 12 days.

Via

Marseilles, 6 to 7 days.

(g) OCEAN RECORDS

Liverpool and Queenstown to America (New York).

|

Year

|

Days

|

Hours

|

Mins

|

Name of Vessel

|

1819

1838

1851

1856

1862

1866

1873

1875

1876

1877

1877

1879

1880

1881

1882

1883

1884

1885

1887

1888

1889

1891

1892

1893

1894

|

22

18

10

10

10

9

9

9

8

8

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

7

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

|

11

10

6

2

19

13

1

17

2

20

18

15

13

11

10

8

3

23

21

18

14

9

6

5

4

1

23

22

21

20

19

19

18

16

14

13

12

9

7

|

15

15

25

42

45

47

48

9

50

48

11

37

53

30

50

4

37

18

51

8

31

42

55

7

50

20

39

18

5

8

31

24

23

47

29

23

|

Savannah (Savannah to Liverpool)

Sirius (Liverpool to New York)

Great Western (Liverpool to New York)

Africa (London to New York)

Asia (Liverpool to New York)

Pacific (Liverpool to New York)

Baltic (Liverpool to New York)

Persia (Liverpool to New York)

Scotia (Liverpool to New York)

Scotia (Queenstown to

New York)

Baltic

City of Richmond

City of Berlin

Britannic

Germanic

Britannic

Arizona (New York to Queenstown)

Arizona (Queenstown to New York)

Servia

City of Rome

Alaska

America

Oregon

Umbria

Etruria

Umbria

Etruria

City of New York

City of Paris

Majestic

City of New York

City of Paris

Teutonic

Majestic

Teutonic

City of Paris

Campania

Lucania

Campania

Lucania

|

Note. — These and

the subsequent lists of "Ocean Records" are reprinted from the

"Daily Mail Year Book" by kind permission.

Southampton

to New York.

| Year |

Name of Vessel |

Company |

Time |

East

or West |

| D. |

H. |

M. |

1881

1883

1882

1884

1885

1886

1887

1889

1889

1893

1893

1893

1894

1896

1897

1897

1897

1900

1900

1902 |

Elbe

Werra

Werra

Eider

Eider

Aller

Aller

Augusta Victoria

Fürst Bismarck.

Fürst Bismarck.

Fürst Bismarck

Paris

New York

St. Paul

St. Louis

Kaiser Wm. der Grosse

Kaiser Wm. der Grosse

Kaiser Wm. der Grosse (To Cherbourg)

Deutschland (To

Plymouth)

Kronprinz Wm. (To Plymouth) |

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

Hamb. Am.

Hamb. Am.

Hamb. Am.

Hamb. Am.

American

American

American

American

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

N.D.L.

Hamb. Am.

N.D.L. |

8

7

7

7

7

7

7

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

5

5

5

5

5 |

0

21

20

18

17

10

8

18

13

11

10

9

7

0

10

22

17

16

7

8 |

0

15

10

44

55

37

14

31

41

35

8

38

18 |

W

W

E

W

W

W

W

W

W

E

E

W

W

W

E

W

E

E

E

E |

| Company |

Service |

Distance |

Time

of

Fastest

Passage |

| D. |

H. |

P. & O.

Orient

Mess. Mar.

Bibby

P. & O.

N. D. Lloyd

City Line

Orient

Aberdeen Line

P. & O.

N. D. Lloyd

Mess. Mar.

N. D. Lloyd

P. & O.

Mess. Mar . |

England

and India, Ceylon, Burma, etc.

Tilbury & Bombay

Tilbury & Colombo

Marseilles & Bombay

Liverpool & Rangoon

Tilbury & Calcutta

Southampton & Colombo

London & Calcutta .

England and Australasia

Tilbury & Sydney

Dover & Sydney

Tilbury & Sydney

Southampton & Sydney

Marseilles & Sydney

England

and China

(Terminal Port, Hong Kong)

Southampton & Hong Kong

Tilbury & Hong Kong, via Marseilles

Marseilles &Hong Kong |

6,570

7,093

4,559

8,162

8,259

7,068

8,259

12,558

12,341

12,555

12,563

10,491

10,178

10,112

8,611 |

22

24

14

23

33

25

26

43

93

43

46

33

35

38

34 |

12

0

23

20

0

0

0

0

10

12

0

0

0

0

0

|

Other

Records (continued)

| Company |

Service |

Distance |

Time of Fastest Passage |

| D. |

H. |

M. |

Trent

Port Morant

Labrador

Parisian

La Savoie

Minneapolis

New England

Tunisian

Scot

Carisbrook Castle

Buluwayo

Medic |

England and the West Indies

Barbados & Plymouth

Bristol & Kingston

Europe and America

Moville & Belle Isle

Moville & Rimouski

Havre & New York

Dover & Sandy Hook

Queenstown & Boston

Rimouski & Moville

England and South Africa

Southampton to Cape Town E. 14

Southampton to Cape Town W. 14

Dartmouth & Durban E. 23

Liverpool & Cape Town |

3,513

*20.59

3,265

2,636

5,981

5,981

6,584

6,100 |

15

11

6

5

8

6

6

14

14

23

19 |

40

12

0

2

2

12

6

11

11

2

14 |

31

42

40

0

13

26

50 |

*

Average knots throughout voyage.

|