| Web

and Book

design, |

Click

Here to return to |

[INTRODUCTION]

MY DEAR COWELL, Two years

ago, when we began (I for the first time) to read this Poem together, I wanted

you to translate it, as something that should interest a few who are worth

interesting. You, however, did not see the way clear then, and had Aristotle

pulling you by one Shoulder and Prakrit Vararuchi by the other, so as indeed to

have hindered you up to this time completing a Version of Hafiz’ best Odes

which you had then happily begun. So, continuing to like old Jámi more and

more, I must try my hand upon him; and here is my reduced Version of a small

Original. What Scholarship it has is yours, my Master in Persian and so much

beside; who are no further answerable for all than by well liking and wishing

publisht what you may scarce have Leisure to find due fault with. Had all the

Poem been like Parts, it would have been all translated, and in such Prose

lines as you measure Hafiz in, and such as any one should adopt who does not

feel himself so much of a Poet as him he translates and some he translates

for — before whom it is best to lay the raw material as genuine as may be, to

work up to their own better Fancies. But, unlike Hafiz’ best — (whose Sonnets are

sometimes as close packt as Shakespeare’s, which they resemble in more ways

than one) — Jámi, you know, like his Countrymen generally, is very diffuse in

what he tells and his way of telling it. The very structure of the Persian

Couplet — (here, like people on the Stage, I am repeating to you what you know,

with an Eye to the small Audience beyond) — so often ending with the same Word,

or Two Words, if but the foregoing Syllable secure a lawful Rhyme, so often

makes the Second Line but a slightly varied Repetition, or Modification of the

First, and gets slowly over Ground often hardly worth gaining. This iteration

is common indeed to the Hebrew Psalms and Proverbs — where, however, the Value of

the Repetition is different. In your Hafiz also, not Two only, but Eight or

Ten Lines perhaps are tied to the same Close of Two — or Three — words; a verbal

Ingenuity as much valued in the East as better Thought. And how many of all the

Odes called his, more and fewer in various Copies, do you yourself care to deal

with! — And in the better ones how often some lines, as I think for this reason,

unworthy of the Rest — interpolated perhaps from the Mouths of his many Devotees,

Mystical and Sensual — or crept into Manuscripts of which he never arranged or

corrected one from the First? This,

together with the confined Action of Persian Grammar, whose organic simplicity

seems to me its difficulty when applied, makes the Line by Line Translation of

a Poem not line by line precious tedious in proportion to its length.

Especially — (what the Sonnet does not feel) — in the Narrative; which I found

when once eased in its Collar, and yet missing somewhat of rhythmical Amble,

somehow, and not without resistance on my part, swerved into that “easy road”

of Verse — easiest as unbeset with any exigencies of Rhyme. Those little Stories,

too, which you thought untractable, but which have their Use as well as Humour

by way of quaint Interlude Music between the little Acts, felt ill at ease in

solemn Lowth Isaiah Prose, and had learn’d their tune, you know, before even

Hiawatha came to teach people to quarrel about it. Till, one part drawing on

another, the Whole grew to the present form. As for the

much bodily omitted — it may be readily guessed that an Asiatic of the 15th

Century might say much on such a subject that an Englishman of the 19th would

not care to read. Not that our Jámi is ever licentious like his Contemporary

Chaucer, nor like Chaucer’s Posterity in Times that called themselves more

Civil. But better Men will not now endure a simplicity of Speech that Worse men

abuse. Then the many more, and foolisher, Stories — preliminary Te Deums to Allah

and Allah’s-shadow Shah — very much about Alef Noses, Eyebrows like inverted

Núns, drunken Narcissus Eyes — and that eternal Moon Face which never wanes from

Persia — of all which there is surely enough in this Glimpse of the Original. No

doubt some Oriental character escapes — the Story sometimes becomes too Skin

and Bone without due interval of even Stupid and Bad. Of the two Evils? — At

least what I have chosen is least in point of bulk; scarcely in proportion

with the length of its Apology which, as usual, probably discharges one’s own

Conscience at too great a Price; people at once turning against you the Arms

they might have wanted had you not laid them down. However it may be with this,

I am sure a complete Translation — even in Prose — would not have been a readable

one — which, after all, is a useful property of most Books, even of Poetry. In studying

the Original, you know, one gets contentedly carried over barren Ground in a

new Land of Language — excited by chasing any new Game that will but show Sport;

the most worthless to win asking perhaps all the sharper Energy to pursue, and

so far yielding all the more Satisfaction when run down. Especially, cheer’d on

as I was by such a Huntsman as poor Dog of a Persian Scholar never hunted with

before; and moreover — but that was rather in the Spanish Sierras — by the Presence

of a Lady in the Field, silently brightening about us like Aurora’s Self, or

chiming in with musical Encouragement that all we started and ran down must be

Royal Game! Ah, happy

Days! When shall we Three meet again — when dip in that unreturning Tide of Time

and Circumstance! In those Meadows far from the World, it seemed, as Salámán’s

Island — before an Iron Railway broke the Heart of that Happy Valley whose Gossip

was the Millwheel, and Visitors the Summer Airs that momentarily ruffled the

sleepy Stream that turned it as they chased one another over to lose themselves

in Whispers in the Copse beyond. Or returning — I suppose you remember whose

Lines they are When Winter

Skies were ting’d with Crimson still

Where Thornbush nestles on the quiet hill, And the live Amber round the setting Sun, Lighting the Labourer home whose Work is done, Burn’d like a Golden Angel — ground above The solitary Home of Peace and Love at such an hour drawing home together for a fireside Night of it with Aeschylus or Calderon in the Cottage, whose walls, modest almost as those of the Poor who cluster’d — and with good reason — round, make to my Eyes the Tower’d Crown of Oxford hanging in the Horizon, and with all Honour won, but a dingy Vapour in Comparison. And now, should they beckon from the terrible Ganges, and this little Book begun as a happy Record of past, and pledge perhaps of Future, Fellowship in Study, darken already with the shadow of everlasting Farewell! But

to turn

from you Two to a Public — nearly as numerous — (with

whom, by the way, this

Letter may die without a name that you know very well how to

supply), — here is

the best I could make of Jámi’s

Poem — “Ouvrage de peu d’

étendue,” says the

Biographie Universelle, and, whatever that means, here

collaps’d into a

nutshell Epic indeed; whose Story however, if nothing else, may

interest some

Scholars as one of Persian Mysticism — perhaps the grand

Mystery of all Religions — an

Allegory fairly devised and carried out — dramatically

culminating as it goes on;

and told as to this day the East loves to tell her Story, illustrated

by Fables

and Tales, so often (as we read in the latest Travels) at the expense

of the

poor Arab of the Desert. The

Proper

Names — and some other Words peculiar to the East — are

printed as near as may be

to their native shape and

sound — ”Sulayman” for Solomon,

“Yúsuf” for Joseph,

etc., as being not only more musical, but retaining their Oriental

flavour

unalloyed with European Association. The accented Vowels are to be

pronounced long,

as in

Italian — Salámán — Absál — Shirin,

etc. The Original

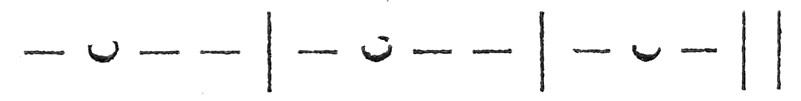

is in rhymed Couplets of this measure: —

which those who

like Monkish Latin may remember in: — “Dum Salámán

verba Regis cogitat,

Pectus intrá de profundis aestuat.” or in English — by

way of asking, “your Clemency for us and for our Tragedy” — “Of Salámán

and of Absál hear the Song;

Little wants Man here below, nor little long.” LIFE OF JÁMI. [I hope the

following disproportionate Notice of Jámi’s Life will be amusing enough to

excuse its length. I found most of it at the last moment in Rosenzweig’s

“Biographische Notizen” of Jámi, from whose own, and Commentator’s, Works it

purports to be gathered.] NÚRUDDÍN

ABDURRAHMAN, Son of Maulána Nizamuddin1

Ahmed, and descended on the

Mother’s side from One of the Four great

“FATHERS” of Islamism, was born A.H.

817, A.D. 1414, in Jam, a little Town of Khorasan, whither (according

to the

Heft Aklím — ”Seven Climates”)

his Grandfather had migrated from Desht of

Ispahan, and from which the Poet ultimately took his Takhalus, or

Poetic name,

JÁMI. This word also signifies “A Cup;”

wherefore, he says, “Born in Jam, and

dipt in the “Jam” of Holy Lore, for a double reason

I must be called JÁMI in

the Book of Song.” He was celebrated afterwards in other

Oriental Titles — “Lord

of Poets” — “Elephant of Wisdom,”

&c., but often liked to call himself “The

Ancient of Herat,” where he mainly resided. When Five

Years old he received the name of Núruddín — the “Light of Faith,” and even so

early began to show the Metal, and take the Stamp that distinguished him

through Life. In 1419, a famous Sheikh, Khwájah Mehmed Parsa, then in the last

year of his Life, was being carried through Jam. “I was not then Five Years

old,” says Jámi, “and my Father, who with his Friends went forth to salute him,

had me carried on the Shoulders of one of the Family and set down before the

Litter of the Sheikh, who gave a Nosegay into my hand. Sixty years have passed,

and methinks I now see before me the bright Image of the Holy Man, and feel the

Blessing of his Aspect, from which I date my after Devotion to that Brotherhood

in which I hope to be enrolled.” So again,

when Maulána Fakhruddín Loristani had alighted at his Mother’s house — “I was

then so little that he set me upon his Knee, and with his Fingers drawing the

Letters of ‘ALI’ and ‘OMAR’ in the Air, laughed delightedly to hear me spell

them. He also by his Goodness sowed in my Heart the Seed of his Devotion,

which has grown to Increase within me — in which I hope to live, and in which to

die. Oh God! Dervish let me live, and Dervish die; and in the Company of the

Dervish do Thou quicken me to Life again!” Jámi first

went to a School at Herát; and afterward to one founded by the Great Timúr at

Samarcand. There he not only outstript his Fellows in the very Encyclopædic

Studies of Persian Education, but even puzzled the Doctors in Logic, Astronomy,

and Theology; who, however, with unresenting Gravity welcomed him — “Lo! a new

Light added to our Galaxy!” — In the wider Field of Samarcand he might have

liked to remain; but Destiny liked otherwise, and a Dream recalled him to

Herat. A Vision of the Great Safi Master there, Mehmed Saaduddín Kaschgari, of

the Nakhsbend Order of Dervishes, appeared to him in his Sleep, and bade him

return to One who would satisfy all Desire. Jámi went back to Herat; he saw the

Sheikh discoursing with his Disciples by the Door of the Great Mosque; day

after day passed by without daring to present himself; but the Master’s Eye was

upon him; day by day draws him nearer and nearer — till at last the Sheikh

announces to those about him — “Lo! this Day have I taken a Falcon in my Snare!” Under him

Jámi began his Súfí Noviciate, with such Devotion, and under such Fascination

from the Master, that going, he tells us, but for one Summer Day’s Holiday into

the Country, one single Line was enough to “lure the Tassel-gentle back again;” “Lo! here am I, and Thou look’st on the Rose!” By and bye

he withdraws, by course of Súfí Instruction, into Solitude so long and profound,

that on his Return to Men he has almost lost the Power of Converse with them.

At last, when duly taught, and duly authorized to teach as Súfí Doctor, he yet

will not, though solicited by those who had seen such a Vision of Him as had

drawn Himself to Herat; and not till the Evening of his Life is he to be seen

with White hairs taking that place by the Mosque which his departed Master had

been used to occupy before. Meanwhile he

had become Poet, which no doubt winged his Reputation and Doctrine far and wide

through Nations to whom Poetry is a vital Element of the Air they breathe. “A

Thousand times,” he says, “I have repented of such Employment; but I could no

more shirk it than one can shirk what the Pen of Fate has written on his

Forehead” — “As Poet I have resounded through the World; Heaven filled itself

with my Song, and the Bride of Time adorned her Ears and Neck with the Pearls

of my Verse, whose coming Caravan the Persian Hafíz and Saadi came forth gladly

to salute, and the Indian Khosrú and Hasan hailed as a Wonder of the World.”

“The Kings of India and Rúm greet me by Letter: the Lords of Irak and Tabríz

load me with Gifts; and what shall I say of those of Khorasan, who drown me in

an Ocean of Munificence?” This,

though

Oriental, is scarcely Bombast. Jámi was honoured by Princes

at home and abroad,

and at the very time they were cutting one another’s Throats;

by his own Sultan

Abou Said; by Hasan Beg of Mesopotamia — “Lord of

Tabríz” — by whom Abou Said was

defeated, dethroned, and slain; by Mahomet II. of

Turkey — “King of

Rúm” — who in

his turn defeated Hasan; and lastly by Husein Mirza Baikara, who

extinguished

the Prince whom Hasan had set up in Abou's Place at Herat. Such is the

House

that Jack builds in Persia. As Hasan

Beg, however — the USUNCASSAN of old European Annals — is singularly connected with

the present Poem, and with probably the most important event in Jámi's Life, I

will briefly follow the Steps that led to that as well as other Princely

Intercourse. In A.H. 877,

A.D. 1472, Jámi set off on his Pilgrimage to Mecca. He, and, on his Account,

the Caravan he went with, were honourably and safely escorted through the

intervening Countries by order of their several Potentates as far as Bagdad.

There Jámi fell into trouble by the Treachery of a Follower he had reproved,

and who (born 400 Years too soon) misquoted Jámi’s Verse into disparagement of

ALT, the Darling Imam of Persia. This getting wind at Bagdad, the thing was

brought to solemn Tribunal, at which Hasan Beg's two Sons assisted. Jámi came

victoriously off; his Accuser pilloried with a dockt Beard in Bagdad Market-

place: but the Poet was so ill pleased with the stupidity of those who believed

the Report, that, standing in Verse upon the Tigris' side, he calls for a Cup

of Wine to seal up Lips of whose Utterance the Men of Bagdad were unworthy. After 4

months' stay there, during which he visits at Helleh the Tomb of Ali's Son,

Husein, who had fallen at Kerbela, he sets forth again — to Najaf, where he says

his Camel sprang forward at sight of Ali’s own Tomb — crosses the Desert in 22

days, meditating on the Prophet’s Glory, to Medina; and so at last to MECCA,

where, as he sang in a Ghazal, he went through all Mahommedan Ceremony with a

Mystical Understanding of his Own. He then

turns Homeward: is entertained for 45 days at Damascus, which he leaves the

very Day before the Turkish Mahomet’s Envoys come with 5000 Ducats to carry him

to Constantinople. Arriving at Amida, the Capital of Mesopotamia (Diyak

bakar), he finds War broken out in full Flame between that Mahomet and Hasan

Beg, King of the Country, who has Jámi honourably escorted through the

dangerous Roads to Tabríz; there receives him in Diván, “frequent and full” of

Sage and Noble (Hasan being a great Admirer of Learning), and would fain have

him abide at Court awhile. Jámi, however, is intent on Home, and once more

seeing his aged Mother — for he is turned of Sixty! — and at last touches Herát in

the Month of Schaaban, 1473, after the Average Year’s absence. This is the

HASAN, “in Name and Nature Handsome” (and so described by some Venetian

Ambassadors of the Time), of whose protection Jámi speaks in the Preliminary

Vision of this Poem, which he dedicates to Hasan’s Son, Yacúb Beg: who, after

the due murder of an Elder Brother, succeeded to the Throne; till all the

Dynasties of “Black and White Sheep” together were swept away a few years after

by Ismael, Founder of the Sofí Dynasty in Persia. Arrived at

home, Jámi finds Husein Mirza Baikara, last of the Timúridae, fast seated

there; having probably slain ere Jámi went the Prince whom Hasan had set up;

but the date of a Year or Two may well wander in the Bloody Jungle of Persian

History. Husein, however, receives Jámi with open Arms; Nisamuddín Ali Schír,

his Vizir, a Poet too, had hailed in Verse the Poet’s Advent from Damascus as

“The Moon rising in the West;” and they both continued affectionately to

honour him as long as he lived. Jámi

sickened of his mortal Illness on the 13th of Moharrem, 1492 — a Sunday. His

Pulse began to fail on the following Friday, about the Hour of Morning Prayer,

and stopped at the very moment when the Muezzin began to call to Evening. He

had lived Eighty-one years. Sultan Husein undertook the Burial of one whose

Glory it was to have lived and died in Dervish Poverty; the Dignities of the

Kingdom followed him to the Grave; where 20 days afterward was recited in

presence of the Sultan and his Court an Eulogy composed by the Vizír, who also

laid the first Stone of a Monument to his Friend’s Memory — the first Stone of “Tarbet’i

Jámi,” in the Street of Mesched, a principal

Thoro’fare of the City of Herát.

For, says Rosenzweig, it must be kept in mind that Jámi was

reverenced not only

as a Poet and Philosopher, but as a Saint also; who not only might work

a

Miracle himself, but leave the Power lingering about his Tomb. It was

known

that once in his Life, an Arab, who had falsely accused him of selling

a Came!

he knew to be mortally unsound, had very shortly after died, as

Jámi had

predicted, and on the very selfsame spot where the Camel fell. And that

Libellous Rogue at Bagdad — he, putting his hand into his

Horse’s Nose-bag to see

if “das Thier” has finisht his Corn, had his

Fore-finger bitten off by the

same — “von demselben der Zeigefinger

abgebissen” — of which

“Verstümmlung” he soon

died — I suppose, as he ought, of Lock jaw. The

Persians, who are adepts at much elegant Ingenuity, are fond of commemorating

Events by some analogous Word or

Sentence whose Letters, cabalistically corresponding to certain Numbers,

compose the Date required. In Jámi’s case they have hit upon the word “KAS,” A

Cup, whose signification brings his own name to Memory, and whose relative

Letters make up his 81 years. They have Taríks also for remembering the Year of

his Death: Rosenzweig gives some; but Ouseley the prettiest, if it will hold — Dúd az Khorásán bar ámed — No Biographer, says Rosenzweig cautiously, records of Jámi that he had more than one Wife (Grand-daughter of his Master Sheikh) and Four Sons; which, however, are Five too many for the Doctrine of this Poem. Of the Sons, Three died Infant; and the Fourth (born to him in very old Age), and for whom he wrote some Elementary Tracts, and the more famous “Beharistan” lived but a few years, and was remembered by his Father in the Preface to his Chiradnameh Iskander — a book of Morals, which perhaps had also been begun for the Boy’s Instruction. Of

Jámi’s

wonderful Fruitfulness — “bewunderungswerther

Fruchtbarkeit” — as Writer,

Rosenzweig names Forty-four offsprings — the Letters of the

word “Jám” completing

by the aforesaid process that very Number. But Shír

Khán Lúdi in his “Memoirs

of the Poets,” says Ouseley, counts him Author of Ninety-nine

Volumes of

Grammar, Poetry, and Theology, which “continue to be

universally admired in

all parts of the Eastern World, Irán, Turán, and

Hindustán” — copied some of them

into precious Manuscript, illuminated with Gold and Painting, by the

greatest

Penmen and Artists of the Time; one such — the

“Beharistan” — said to have cost

Thousands of Pounds — autographed as one most precious

treasure of their

Libraries by two Sovereign Descendants of TIMÚR

upon the Throne of Hindustán;

and now reposited away from “the Drums and

Tramplings” of Oriental Conquest in

the tranquil Seclusion of an English Library. Of these

Ninety-nine, or Forty-four Volumes few are known, and none except the Present

and one other Poem ever printed, in England, where the knowledge of Persian

might have been politically useful. The Poet’s name with us is almost solely

associated with “YÚSUF AND ZULAIKHA,” which, with the other two I have

mentioned, count Three of the Brother Stars of that Constellation into which

Jámi, or his Admirers, have clustered his Seven best Mystical Poems under the

name of “HEFT AURANG” — those “SEVEN THRONES” to which we of the West and North

give our characteristic Name of “Great Bear” and “Charles’s Wain.” He must have

enjoyed great Favour and Protection from his Princes at home, or he would

hardly have ventured to write so freely as in this Poem he does of Doctrine

which exposed the Súfí to vulgar abhorrence and Danger. Hafiz and others are

apologized for as having been obliged to veil a Divinity beyond what “THE

PROPHET” dreamt of under the Figure of Mortal Cup and Cup-bearer. Jámi speaks

in Allegory too, by way of making a palpable grasp at the Skirt of the

Ineffable; but he also dares, in the very thick of Mahommedanism, to talk of

REASON as sole Fountain of Prophecy; and to pant for what would seem so

Pantheistic an Identification with the Deity as shall blind him to any

distinction between Good and Evil.2 I must not

forget one pretty passage of Jámi’s Life. He had a nephew, one Maulána

Abdullah, who was ambitious of following his Uncle’s Footsteps in Poetry. Jámi

first dissuaded him; then, by way of trial whether he had a Talent as well as a

Taste, bid him imitate Firdusi’s Satire on Shah Mahmúd. The Nephew did so well,

that Jámi then encouraged him to proceed; himself wrote the first Couplet of

his First (and most noted) Poem — Laila & Majnun. This Book of which the Pen has now laid the Foundation,

May the diploma of Acceptance one day befall it, —

1

Such final “uddins” signify “OF THE

FAITH.” “MAULÁNA” may be taken

as “MASTER” in Learning, Law, etc. 2

“Je me souviens d’un Prédicateur

à

Ispahan qui, prêchant un jour dans une Place publique, parla

furieusement

contre ces Soufys, disant qu’ ils étoient des

Athées à bruler; qu ‘il

s’étonnoit qu ‘on les laissât

vivre; et que de tuer un Soufy étoit une Action

plus agréable à Dieu que de conserver la

Vie à dix Hommes de Bien. Cinq ou Six

Soufys qui étoient parmi les Auditeurs se

jettèrent sur lui après le Sermon et

le battirent terriblement; et comme je m’efforçois

de les empêcher ils me

disoient — ‘Un homme qui prêche le Meurtre

doit-il se plaindre d’être

battu?’” — CHARDIN. |