| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER IX THE CITY OF THE FRIENDS Time and change have

touched Philadelphia with gentle hand. The Friends are, in the great

essentials, still its dominant class, and this fact appears not only in

its

asylums, its hospitals, and its practical methods of helping men to

help

themselves, but in a prudence of thought and action that is ever

reluctant to

prefer the new to the old. Thus it is that no New World city harbors

more

numerous or more eloquent reminders of the past, or in ancient

buildings and

landmarks bound up with great names and great events offers to the

wayfarer a

richer or more varied store of historic associations. Not to the coming of Penn,

but to the issue of a dream cherished by Gustavus Adolphus, attaches

the oldest

authentic legend of Philadelphia. A score of years before the Quaker

leader was

born the heroic and generous Swede, moved thereto by the bigotry and

poverty of

the age in which he lived, conceived the idea of founding in America a

city

“where every man should have enough to eat and toleration to worship

God as he

chose.” Gustavus's life ended before his dream could be fulfilled, but

eleven

years later the girl Queen Christina and her chancellor despatched an

expedition in the dead king's name. This colony of “New Sweden,” as it

was

called, effected a lodging-place along the banks of the Schuylkill and

Delaware,

in that part of Philadelphia now known as Southwark. The narrow strip of ground

on which the Swedes made their homes is given over in these latter days

to ship

stores, junk-shops, and salty, tarry smells, while a long line of

ships, come

and to go, walls in the view of the river; but if one might be frisked

by the

mere magic of a wish back to the middle years of the seventeenth

century, he

would find instead the low huts of the Norseland pioneers dotting green

banks

on the edge of a gloomy, unbroken forest, with hemlocks and nut trees

nodding

atop. Here dwelt, in peace and plenty, and “great idleness,” if an old

chronicle is to be believed, the long forgotten Swansons, Keens,

Bensons,

Kocks, and Rambos, some of them mighty hunters when the deer came close

up to

the little settlement and nightly could be heard the cry of panthers or

bark of

wolves. At Passajungh was the humble white-nut dwelling of Commander

Sven

Schute, whom Christina called her “brave and fearless lieutenant,” and

at

“Manajungh on the Skorkihl” there was a stout fort of logs filled in

with sand

and stones. Descendants on the female side of these

first

settlers are still to be found in the city, but Philadelphia's only

relic in

stone and mortar of the men who were once lords of all the land on

which it was

built is Gloria Dei, better known as Old Swedes' Church. Each

successive

sovereign of Sweden, loyal to the favorite idea of Gustavus, kept

affectionate

watch over the tiny settlement on the Delaware, and when the colonists

begged

“that godly men might be sent to them to instruct their children, and

help

themselves to lead lives well pleasing to God,” two clergymen, Rudman

and

Bjork, were despatched by Charles XII. in answer to their prayer. These

missionaries reached the colony in June, 1697, and were received, as

the

ancient record states, “with astonishment and tears of joy.” Soon after

their

arrival Gloria Dei was built in a fervor of pious zeal, carpenters and

masons

giving their work, and the good pastor daily carrying the hod. When it

was

finished Swedes, Quakers, and Indians came to wonder at its grandeur,

and it

long remained the most important structure in the little hamlet.

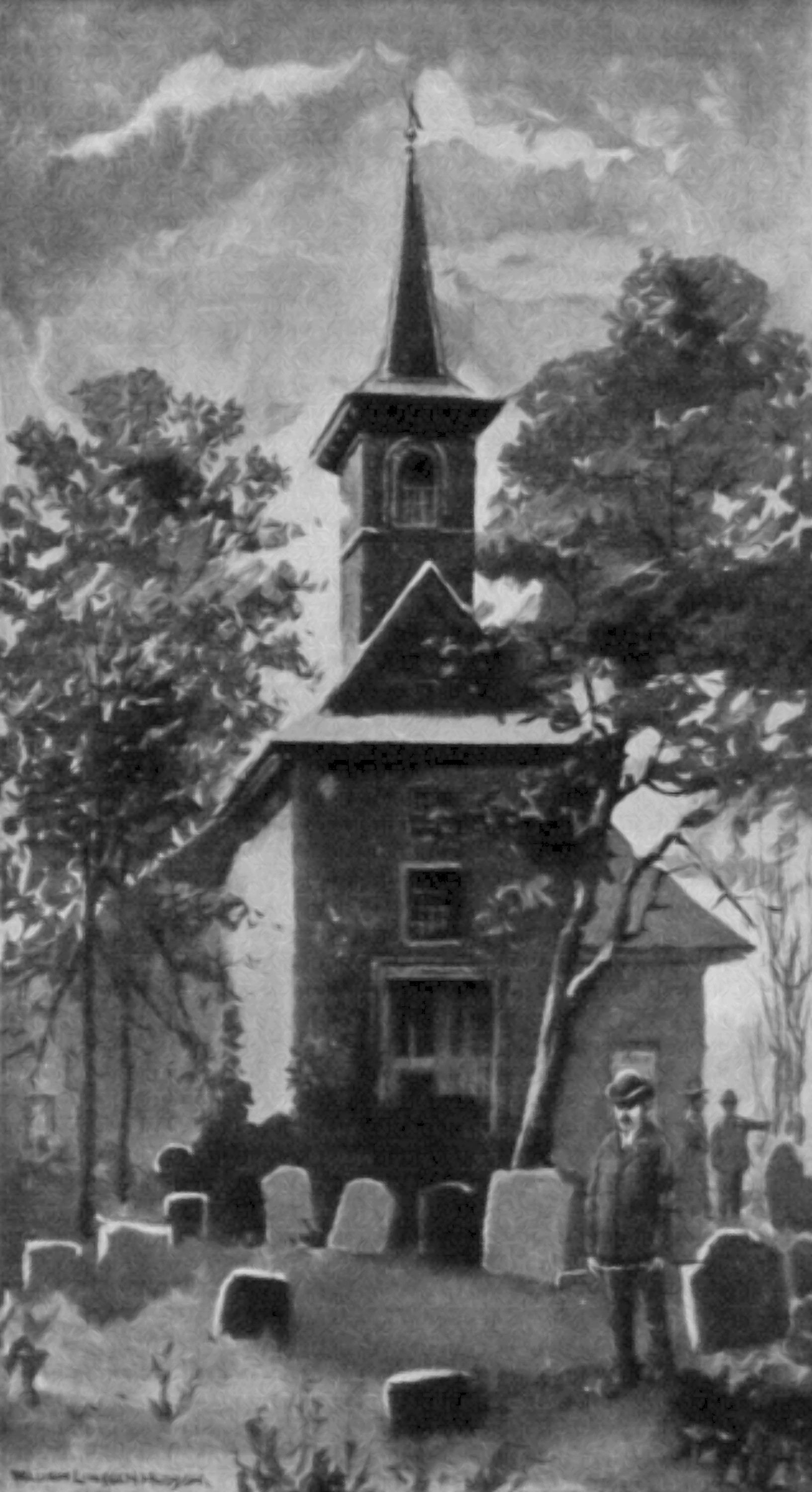

Old Swedes' Church,

Philadelphia Old Swedes' holds its

original site in Southwark, banked in by the sunken graves of its early

worshippers. The main body of the building is unaltered to the present

day. The

carvings inside, the bell, and the communion service were sent out from

the

motherland, given by the king “to his faithful subjects in the far

western wilderness;”

and from Sweden came also the chubby gilt cherubs in the choir which

still

sustain the open Bible, with the speaking inscription, “The people who

sat in

darkness have seen a great light.” Tablets in the chancel record the

sacrifices

and sufferings of the early pastors of the church who sleep within its

walls.

The last of these was Nicholas Collin, whose period of zealous service

covered

the better part of fifty years, and who with his devoted wife Hannah is

buried

just below the little altar. Another familiar face in Gloria Dei in the

opening

years of the century was that of Collin's friend, Alexander Wilson,

then the

half-starved, ill-paid master of a little school at nearby Kingsessing.

The

great ornithologist is buried in the graveyard of the church in which

he asked

that he should be laid to rest, as it was “a silent, shady place, where

the

birds would be apt to come and sing over his grave.” When Old Swedes' was built

the only house nearby was that of Swan Swanson, from whose three sons

Penn,

when he came, bought the land to lay out his town of Philadelphia. That

was in

1682. A small band of pioneers had preceded the Proprietor, and he was

followed

by three-and-twenty ships, filled with Quakers of all classes. The

city,

speedily laid out by Thomas Holme, extended from river to river, and

appeared

magnificent — on paper; but, truth to tell, most of the new-comers

following

the example of the Swedes, who gave them kindly welcome, built their

homes in

the corner by the Delaware; and for nearly a hundred years the town

consisted

of but three or four streets, running parallel with that stream. Back

of these

streets lay a gloomy forest, drained by creeks, which cut the town into

three

or four parts before emptying into the Delaware. As late as the opening

year of

the Revolution Philadelphia extended only from Christian to Callowhill

Streets,

north and south, and until well on in the present century Frankford,

Roxborough, and Germantown were reckoned distant hamlets, being seldom

visited

by the people of the town. On a “pleasant hill”

overlooking the river, and with a noble sweep of forest land between,

the

Proprietor reserved a lot for himself, on which he had built the house,

which

he gave to his daughter Lætitia. The brick and other material for this

house

were brought from England, and within its walls Penn passed most of the

busy

and fruitful days of his first visit, preferring it to the costly and

imposing

pile he had reared at Pennsbury. The searcher after the site of the

Lætitia

House finds it in Lætitia Court, between Chestnut and Market, Second

and Front

Streets, — a narrow, dirty alley, cut off from the sunlight by the

backs of the

great importing houses which now cover the wooded glades where, in the

Proprietor's time, deer ranged at will. Elsewhere in Philadelphia there

are few

traces of the reign of the Penns. One of the few is what is known as

Lansdowne,

now included in Fairmount Park, which was once owned and occupied by

John Penn,

governor of the colony in its last days of submission to the British

crown. The Lætitia House was the

first brick building erected in Philadelphia. Most of the dwellings

built

during the earlier years of the Quaker occupancy, some of which are

still

standing within the precincts of the “old town,” were of black and red

English

brick, or of mortar mixed with broken stone and mica. They were, as a

rule,

small, hipped-roofed, two-storied structures, inferior in every way to

those

now occupied by people of moderate incomes. Gradually, however, as time

went

on, the more shrewd or fortunate among the Quakers acquired large

means, while

the steady growth of the town attracted to it a number of men, not

followers of

Penn, who brought with them or soon became possessed of much solid

wealth. From

these changed conditions resulted a division into two classes of the

social

life of the town, and the building of many splendid houses, the

grandeur of

which is reflected in more than one diary and chronicle of the period.

Among

these were the Wharton House, in Southwark; Wilton, the estate of

Joseph

Turner, in the Neck; Woodlands, Governor Hamilton's great house at

Blockley

Hill; the Carpenter mansion, which stood at Seventh and Chestnut

Streets,

surrounded by magnificent grounds; the spacious home of Isaac Norris on

Third

Street; the Pemberton countryseat, on the present site of the Naval

Asylum;

and, chief of all, Stenton, on the cityward site of Germantown. Stenton, “a palace in its

day,” according to old Watson, was built in 1731 by James II. Logan, a

keen-witted Scotchman turned Quaker, who, as agent of the Proprietor,

stood

between Penn and his debts on one hand and an impatient, grasping

colonial

Assembly on the other, serving both with fidelity and to good purpose.

He was

generous as well as shrewd, and at his death left the residue of a

large estate

to the public, including the splendid bequest of the Loganian Library,

a

literary treasure-house at any time, but invaluable a century and a

half ago,

when books were luxuries only for the wealthy. Logan was also the

trusted

friend of the Indians, who came in large deputations to visit him, and

pitched

their wigwams on the great lawn at Stenton. Logan, the famous Mingo

chief, was

the namesake of the good Quaker, and, in youth, was often numbered

among the

latter's savage guests. Stenton, in its builder's

time, was the seat of a sober but large hospitality, and the centre of

the

social life of the Quakers. Here gathered the grave, mild-mannered men

and the

quiet, sweet-faced women, who look down upon us from old family

portraits, and whose

rare and admirable traits included a perfect simplicity and that repose

which

can belong only to people who have never doubted their own social

position.

“The men and women who met at Stenton,” writes one of Logan's

descendants,

“talked no scandal and spoke not of money.” Logan's home was the resort

of the

colonial governors, not only of Pennsylvania but other of the

provinces; and

among his frequent guests were William Allen, Isaac Norris, the three

Pembertons, and that Nicholas Waln who, educated for the bar, after

long

practice in the courts, so took to heart the moral short-comings of his

fellow-lawyers that he fell into a dangerous illness. He rose from his

bed a

changed man, went into the meeting and became a weighty and powerful

preacher. However, not all of the

guests at Stenton were as serious-minded as Waln. The men could laugh

and jest

on occasion; and their wives and daughters were pretty sure to display

a

woman's love of finery, setting off their beauty by white satin

petticoats,

worked in flowers, pearl satin gowns, gold chains, and seals engraven

with

their arms. Nor are lacking stray hints of love and courtship which

lend a

winsome interest to the old house, for pretty Hannah Logan's lover,

returning

with her from a summer day's fishing in the Wissahickon, writes in his

diary

that when they “came home there was so large a company for tea, that

Hannah and

I were set at a side table, and there we supped — on nectar and

ambrosia.”

Another of Stenton's daughters was Deborah Logan, a fair and gracious

woman in

youth and old age, who in the “Penn and Logan Correspondence,” compiled

by her

and by her given to the world, has given us a faithful and winning

picture of

the age in which she lived, an age marked by a lack of self-assertion

and an

inborn hatred of brag, whose influence abides in the Philadelphia of

to-day. Different in religion,

tastes, and habits from the Friends were the men of wealth and their

families

who constituted a not inconsiderable portion of Philadelphia's polite

society

during its first century of existence. These were the merchants and

ship-owners, who, though not followers of Penn, had been attracted to

his town

by its successful growth, and who, opening a trade to the West Indies

and

England, from small ventures quickly amassed colossal fortunes. The

wives and

daughters of these merchant princes, most of whom could show ancestral

bearings, followed afar off the reports of English fashions. They rode

on

horseback or went in sedan-chairs to pay visits; their kitchens swarmed

with

slaves and white redemptionists; they dined and danced, and — gambled;

and they

worshipped of a Sunday in a church dedicated to the Anglican creed. The parish of Christ

Church was thirty-two years old when the present building was commenced

in

1727. William of Orange was an active promoter of the parish, and the

service

of plate now in use in the church was a gift from Anne. Designed by the

architect of Independence Hall, Christ Church presents many points of

similarity to that historic structure, and is likewise closely

identified with

the struggle for independence. Here worshipped General and Lady

Washington,

Samuel and John Adams, Patrick Henry, James Madison, John Hancock, and

Richard

Henry Lee. Under its roof the Episcopal Church in America was

organized, in

1785, and within its walls is now housed a rare and interesting

collection of

ancient volumes, furniture, pictures, and tablets, each of interest to

the

student and lover of the past. One of the first rectors

of Christ Church was a Rev. Mr. Coombe. He was a Loyalist, and during

the early

days of the Revolution returned to England, where lie finally became

chaplain

to George III. It is probably from him or one of his family that an

alley, a

short distance above Christ Church, and running eastward, takes its

name. Here

it was that the namesake and heir of William Penn, when he came over to

play

the prince in the colony, once got into a brawl. He was spending an

evening in

Enoch Story's inn, when he fell to quarrelling with some of his

fellow-citizens

who were acting as the watch. The sober Friends, who had little

patience with

princely debauchees, arrested the young fellow for this affray,

whereupon he

incontinently forsook the Society for the Church of England, in which

faith the

descendants of Penn have ever since remained. Coombe's Alley, in the

younger Penn's time, was a prosperous quarter, and it still bears

traces of

better days. In 1795 it had a very large population for such narrow

limits, — boasting

its half-dozen boarding-houses, its merchants and laborers, its

soldiers and

mariners, its bakers and hucksters. Nor was it without its cares and

troubles;

for during the famous epidemic of 1793 thirty-two people died in the

course of

a year in this one small street. The old houses still standing in it

are built

of the red and black bricks so plentiful in the city's youth. In most

cases

curious wooden projections, like unfinished roofs, divide the first

story from

the second, making the latter look as though they had been an

after-thought. The chimes of Christ

Church, which on July 4, 1776, proclaimed the tidings of independence,

were

paid for by the proceeds of a lottery conducted by Benjamin Franklin.

The

printer-patriot takes his rest under a flat marble slab in the crowded

burial-ground at the corner of Fifth and Arch Streets, but his life and

works

are still vital influences in the city of his adoption. In truth, his

advent

into the town at the age of seventeen marks the date of the birth of

the

intellectual life of Philadelphia. Blending shrewd common sense with

keen, fine

humor, and a capacity for winning and holding friends, the young

printer, in a

space of time signally brief, gained recognition as a leader in the

town. Its

old respectabilities eyed him askance, but following where he led, made

him

clerk of Assembly, postmaster, and agent to England, or looked on with

grudging

assent as, out of the unlikely material of his fellow-workmen, he

established

his Junto, or philosophic club, and founded the first subscription

library in

the country, the first fire and military companies in the colony, and

the first

academy in the town, just as, in after-years, they held aloof while he,

with

two or three other Philadelphia radicals, united with Southerners and

New

Englanders in signing the papers which gave freedom to the country and

immortality to its makers. Though every effort for

the improvement of colonial Philadelphia can be traced to Franklin, one

comes

closest to him, perhaps, in the old library which grew out of his Junto

club,

and which, guarded by an effigy of its founder, long stood close beside

the

State-House, just out of Chestnut Street, but has now been removed to

Park

Avenue and Locust Street. Inside are dusky recesses filled with dusty

time-worn

folios, and from one of the galleries the great Minerva which presided

over the

deliberations of the Continental Congress looks down upon a desk and

clock once

owned and used by William Penn. The noise and hurry of the modern world

never

reach this cloistered recess, crowded with the shades of scholars dead

generations ago, and an hour spent therein is a page from the past that

will

linger long in the memory. A quaint hipped-roofed

house standing on Front Street, a few doors above Dock, recalls another

significant incident in the life of Franklin. To this house, erstwhile

occupied

by one generation after another of Quakers, he was conducted upon his

return

from England, just before the opening of the Revolution. Philadelphia

had for

some time presented the spectacle of an exceptionally temperate and

prudent

community slowly rousing to temperate, prudent resistance to injustice.

The

Friends, prompted by motives for which we can scarcely blame them, were

opposed

to armed rebellion; so were the great merchants, to whom a war with

England

threatened financial ruin. Facing the other way were a numerous body of

citizens eager for the moment of conflict. Loyalist and patriot alike

waited

anxiously for Franklin and his first words of counsel. The Friends in a

body

met him as he landed, and without a word, in solemn procession,

escorted him to

the Front Street house. Entering, they all seated themselves, still

silent,

waiting for the Spirit of God first to speak through some of them,

when, as we

are told, Franklin stood up and cried out with power, “To arms, my

friends, to

arms!” That his warning fell on reluctant if unheeding ears is known to

all.

The sudden influx of the leaders of the Revolution, in the stormy days

that

followed, pushed the Quaker class and the Tory families for the moment

to the

wall; and during the most glorious period of the city's history her old

rulers,

with few exceptions, yielded their places to strangers. Still another reminder of

the Philadelphia that Franklin knew is the house of his longtime

friend, John

Bartram, which yet stands near the Schuylkill, on the Gray's Ferry

Road. The

former home of the Quaker botanist is of graystone, hewn from the solid

rock

and put in place in 1734 by Bartram's own hands; for among his other

accomplishments he reckoned that of practical stonemason. A dense mat

of ivy,

out of which peep two windows, cover its northern end. The south end,

nearly

free from vines, is also pierced with two large windows, the sills

thereof

curiously carved in stone-work. Between these two windows, upper and

lower, a

smooth, square block of stone has been carved with this inscription: 'Tis God alone,

Almighty

Lord, The Holy One by me

adored.

John

Bartram, 1770. Dormer-windows jut out

from the roof of the old house, and between its two projecting wings

runs a

wooden porch, supported by a massive stone pillar, the front covered by

an aged

but still lusty Virginia creeper. Time has worked small change in the

ancient

structure. The great fireplace in its central room has been filled up,

and the

old Franklin stove, a present, mayhap, from Benjamin himself, has been

removed

from the sitting-room, but beyond this everything stands as it did in

its first

owner's time. Back of the sitting-room, in the wing looking towards the

south,

is an airy apartment that once did duty as a conservatory. Beside this

room is

the botanist's study, with windows facing the south and east. It was

here in

later years that Alexander Wilson wrote the opening pages of his great

work on

ornithology, under the patronage and aided by the suggestions of

William

Bartram, the successor of his father John, and himself a naturalist of

learning

and repute. Against the front of the

house grows a Jerusalem “Christ's-thorn,” and on one side of it a

gnarled and

tangled yew-tree, both planted by the elder Bartram's hands. Thence the

famous

botanic garden, the first one on this continent, which the good Quaker

constructed untaught, planting it with trees and shrubs gathered by

himself in

countless journeys through the wilderness, slopes gently downward to

the banks

of the Schuylkill. When Charles Kingsley visited Philadelphia, some

years ago,

his first request was to be taken to this old garden, which has now

become a

grove of trees, rare and various, of native and foreign growth, —

deciduous trees

and evergreens of many varieties, blossoming shrubs, white and red

cedars,

spruce, pines, and firs, thick with shade and spicy with odor. At the

garden's

lower edge and close to the river once stood a cider-mill, of which all

that

remains is a great embedded rock, hewn flat, with a circular groove in

it, in

which a stone dragged by horses revolved, crushing the apples to pulp.

A

channel cut through the rock leading from the groove served to convey

the juice

from the mill. It was a piece of Bartram's own handiwork, another

example of

the combining of the practical and ideal in his sturdy nature. Not far

from

this old cider-mill stands a stone marking the grave of one of

Bartram's

servants, an aged black, one time a slave, for even the Quakers held

slaves in

colony times. At the time of the old negro's death, however, he was a

freeman,

and had been for years, for Bartram was one of the earliest

emancipators of

slaves in America. All that Bartram, whom

Linnæus pronounced “the greatest of living botanists,” was enabled to

achieve

he owed, in the main, to his own efforts. His life was of the simplest

character; and to the last he retained the habits and customs of the

plain

farmer folk, of whom he accounted himself one. Touching also in its

modesty and

simplicity is his own account of how he became a botanist. “One day,”

he wrote

in his later years, “I was busy in holding my plough, and being aweary

I sat me

beneath the shade of a tree to rest myself. I cast mine eyes upon a

daisy. I

plucked the pretty flower, and viewing it with more closeness than

common

farmers are wont to bestow upon a weed, I observed therein many curious

and

distinct parts, each perfect in itself, and each in its way tending to

enhance

the beauty of the flower. ‘What a shame,’ said something within my

mind, ‘that

thou hast spent so many years in the ruthless destroying of that which

the Lord

in His infinite goodness hath made so perfect in its humble place

without thy

trying to understand one of the simplest leaves!’ This thought awakened

my

curiosity, for these are not the thoughts to which I had been

accustomed. I

returned to my plough once more; but this new desire for inquiry into

the

perfections the Lord hath granted to all about us did not quit my mind;

nor

hath it since.” The path upon which he

thus set forth made the Quaker farmer the peer and fellow of the

greatest

naturalists of his time, and in his later days royal botanist for the

provinces. Bartram lived to the age of eighty, hale and strong to the

last, his

only trouble being his dread that the ravages of the Revolution might

reach his

peaceful garden. His fear was groundless, for all alike reverenced and

loved

the gentle old man. His death occurred on the morrow of the battle of

Brandywine. Philadelphia, in 1774, had

grown to be a thriving, well-conditioned, prosperous city of thirty

thousand

inhabitants, the largest in the colonies, and, thanks to the genius of

Franklin, paved, lighted, and ordered in a way almost unknown in any

other town

of that period. It was, also, as nearly as possible, the central point

of the

colonies. Thus both its position and its condition drew to it the

strangers

from the North and the South, who began to appear in the streets and

public

places in the late summer of 1774. Few of these strangers were

commonplace;

most of them gave evidence of distinction, and all were prompt in

setting about

the work that had brought them from their widely-scattered homes. The members of the first

colonial Congress having found, on reaching Philadelphia, that the

State-House

was already occupied by the Provincial Assembly, determined to hold

their

meetings in the hall, on Chestnut Street above Third, built by the

Honorable

Society of Carpenters, and still used by them. Accordingly, on the

morning of

September 5 they assembled at the City Tavern, where most of them were

quartered, and went thence together to this little hall. We are told

that the

Quakers watched the little procession gloomily, but it was made up of

men who

have assumed for us heroic proportions. There were John and Samuel

Adams, of

Massachusetts, the latter with stern, set face of the Puritan type; the

venerable Stephen Hopkins, of Rhode Island; Roger Sherman, of

Connecticut, tall

and grave; John Jay, of New York, with birth and breeding written in

his clean-cut

features; Thomas McKean, of Pennsylvania, an Anak among patriots, and

lank

Cæsar Rodney, of Delaware. There, too, were Christopher Gadsden and the

two

Rutledges, from South Carolina, while Peyton Randolph, full of years

and

honors, headed a delegation from Virginia which included Patrick Henry,

Richard

Henry Lee, and another better known than any of them, with his

soldier's fame

won on hard-fought fields, — George Washington, of Mount Vernon. What

the

grave, silent Virginia colonel had done was known to every onlooker.

What he

was yet to do no one dreamed, but we may easily believe that the people

who lined

the streets that sunny September morning felt dumbly what Henry said

for those

who met him in the Congress, “Washington is unquestionably the greatest

of them

all.” The work done in the

assembly-room of the hall of the Carpenters in the autumn days of 1774

cleared

the way for the call to arms. When the Congress met again, in May of

the

following year, it held its deliberations in the State-House, and

thenceforward

the history of the country takes this long, old-fashioned structure of

red

brick, with its white marble facings and thick window-sashes, as its

central

point of interest. In the little square before it gathered excited

groups of

patriots and Loyalists on the memorable days and still more memorable

nights

when within its walls, behind closed doors, the delegates of thirteen

colonies

were debating a resolution to declare them independent. On July 2,

1776, the

resolution was passed. “A greater question,” says Adams, “perhaps never

was

decided among men.” The Declaration was signed

by John Hancock and Charles Thomson, president and secretary of the

Congress,

on the Fourth of July, this act taking place in the east room of the

State-House on the lower floor, where during the next four weeks the

other

members of the Congress also affixed their signatures. The Declaration

had been

written by Thomas Jefferson in his lodging-house, which stood until

recently at

the southwest corner of Market and Seventh Streets. It was made public

on the

morrow of the Fourth, but was not officially given to the people until

noonday

on the 8th of July, when it was read to a great crowd in the

State-House yard.

The stage on which the reader stood was a rough platform, built some

years

before by David Rittenhouse, the astronomer, as an observatory from

which to

note certain important movements of the planets. The use to which its

builder had put it had resulted in the first determination of the

dimensions of

the solar system; and now serving a not less noble purpose, it heralded

a

platform of human rights broad enough for the whole world to stand

upon. Cheers

rent the welkin when the reading of the Declaration was finished;

bonfires were

lighted; the chimes of Christ Church rang until nightfall, and the old

bell in

the State-House tower gave a new and noisy meaning to the words

inscribed on

its side a quarter of a century before, — “Proclaim liberty throughout

the land

and to all the inhabitants thereof.” Thus the Republic was born.

The story of the days of storm and stress that followed has been

written again

and again, and ever finds new chroniclers; but over one act of the

great

Congress that adopted the Declaration the pen must always linger with

affectionate touch. On June 14, 1777, it was resolved by the Congress

“that the

flag of the United States be thirteen stripes alternately red and

white, and

that the union be thirteen white stars, in a blue field, representing a

new

constellation.” The first flag was modelled under the personal

supervision of

Washington, who was then in Philadelphia, and a committee from the

Congress.

They called upon Mrs. Elizabeth Ross, who conducted an upholstery shop

in the

little house yet standing at 239 Arch Street; and from a rough draft

which

Washington had made she prepared the first flag. The general's design

contained

stars of six points, but Mrs. Ross thought that five points would make

them

more symmetrical. She completed the flag in twenty-four hours, and at

Fort

Schuyler, New York, a few weeks later, it received its baptism of fire.

“Betsy”

Ross was appointed by Congress to be the manufacturer of the government

flags,

and she followed this occupation for many years, being succeeded by her

children. In September, 1777, the

British entered Philadelphia, and it was not reoccupied by the patriot

army

till 1779. Meantime in its northern suburbs was fought the desperate

and

luckless battle of Germantown. About many of the old houses of that

village

hang pulse-moving legends of the one eventful day in its history. Chief

among

these is the Chew House, built in 1763, about which the fight raged

furiously

for hours. This house was held by Colonel Musgrave and six companies so

long

that a gallant lad, the Chevalier de Manduit, with Colonel Laurens,

crept up to

fire it with a wisp of straw. They escaped under a shower of balls,

while a

young man who had followed them fell dead at the first shot. Another old house at the

corner of Main Street and West Walnut Lane was used as a hospital and

amputating-room, while the Wistar House, built in 1744, was occupied by

some of

the British officers, one of whom was General Agnew, “a cheerful and

heart-some

young man,” according to tradition. As he passed out to join his

command he

encountered the old servant Justinia at work in the garden, and bade

her hide

in the cellar until the fighting was at an end. But Justinia refused to

obey,

and had not finished hoeing her cabbages when Agnew was carried in

wounded unto

death, a decoration which he wore on his breast having offered a mark

for a

patriot rifleman. A quaint room of the Wistar House, now filled with

relics of

early times, is the one in which the heartsome young officer breathed

out his

life. His blood still stains the floor. Yet another reminder of

the Revolution is to be encountered in a stroll about Germantown, for

in the

yard of St. Michael's Lutheran Church sleeps one who played a useful if

humble

part in the struggle. Chris. Ludwick was a Dutch baker of Germantown,

who had

saved a comfortable fortune before the commencement of the seven years'

war.

Half of this property he offered to the service of his country,

swearing at the

same time never to shave until her freedom was accomplished. Washington

gave

him charge of the ovens of the army, and Baker-General Ludwick, with

his great

grizzled beard and big voice, was a familiar and not unheroic figure in

the

camp. He died an old man of eighty, in 1801, leaving his entire fortune

for the

education of the poor. After the Revolution came

the making of the Constitution and the setting afoot of the Union, with

Philadelphia as the national capital. The city's condition during the

years in

which it was controlled by Washington's simple high-bred court is known

to

every reader of history. In the great house once occupied by Richard

Penn,

afterwards owned by Robert Morris, and gone long since from the south

side of

Market Street, Washington had his home from 1791 to 1797. It was deemed

the

fittest dwelling in the city for the President of the new nation, and

must have

well deserved to be called a mansion. There are many pleasing pictures

of the

life led there by Washington and his family, but none half so winsome

and

delightful as that of a girl friend of Nelly Custis, who spent a night

in the

President's house. “When ten o'clock came,” she tells us, “Mrs.

Washington

retired, and her granddaughter accompanied her, and read a chapter and

psalm

from the old family Bible. All then knelt together in prayer, and when

Mrs.

Washington's maid had prepared her for bed Nelly sang a soothing hymn,

and,

leaning over her, received from her some words of counsel and her kiss

and

blessing.” One other picture, and the

last, of the Philadelphia of a century ago. The time was March 4, 1797,

and a

vast crowd had assembled in the State-House to witness the inauguration

of John

Adams as Washington's successor. Few in the throng, however, gave heed

to the

entrance of the new chief executive. Instead, every eye was bent upon

Washington, for the people knew it was to be the last public appearance

of their

idol. “He wore,” writes an eye-witness, “a full suit of black velvet,

his hair

powdered and in a bag, diamond knee-buckles, and a light sword with

gray

scabbard.” Beside him was the new Vice-President, Jefferson, awkward

and

ungainly; and nearby was the boyish Madison and the burly Knox. When

Adams had

read his inaugural and left the room the crowd cheered, but did not

move.

Jefferson, after some courteous parley, took precedence of Washington,

and went

out. Still the people remained motionless, watching the noble figure in

black;

nor did any one stir until Washington descended from the platform and

left the

hall to follow and pay his respects to the new President. Then they and

all the

crowd in the streets moved after him, but in silence. Upon the

threshold of the

President's lodgings he turned and faced this multitude of nameless

friends.

“No man ever saw him so moved.” The tears rolled unchecked down his

cheeks.

Then he bowed slowly and low and went within. After he had gone a

smothered

sound, not unlike a sob, went up from the crowd, for they knew that

their hero

had passed away to be seen of them no more. |