| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER VII THE WEST BANK OF THE HUDSON The west bank is the poor

man's side of the Hudson, and such it has been ever since the first

white

settlers made their homes there. From Albany southward to Kingston, and

back to

the Catskills, it was settled by the Dutch and a handful of

impoverished

Huguenots, — farmers and farm laborers who took up small holdings,

which have

been held by their descendants for upward of two hundred years. It is a

country

with many school-houses but few churches, and more drug stores than

saloons.

The wise man rambling through it avoids the more modern hotels to stop

at the

old Dutch inns, where he will see gray-haired, smooth-shaven hotel

clerks, the

register on the bar, the floor clean from its morning scrubbing, a

dinner at

twelve o'clock with two kinds of meat, three kinds of vegetables, and

four

kinds of dessert, and after dinner can hear the venerable citizens,

standing

out on the porch, talk of things that happened during the Revolution,

with

occasional anecdotes about the French and Indian wars. The people of the west

bank are a slow-going folk. The telegraph and telephone wires pass

their doors,

but they are not generally used by the old citizens. Neither is the

railroad,

the construction of which is within the recollection of the children of

this

generation. They prefer the boats which go from one town to another at

intervals to accommodate the inhabitants, and count them good enough to

travel

by if any one wants a change from driving in a buggy. There is absence

of

poverty and little crime and few tramps. Tramps prefer the cast bank,

where the

fine country-places are. In the winter when the big ice-houses are

being filled

there is more of a turbulent element, but that causes little trouble,

and comes

from the east bank more than the west. Cutting ice along the west bank

is the

winter work for the farmers who care to piece out their income of the

summer.

The little graveyards are more frequent than the little villages. The

gravestones are close together under a few trees in the corner of a big

field,

the way that a brood of chickens cluster in the yard of a house. The

graveyards

contain the records of the family from the time its founders settled in

Ulster

County to escape religious persecution at their birthplace or factional

disturbances in Albany. Despite their comparative

poverty the people of the west bank have brought forth many strong and

brainful

men, and have made their share of history, — a fact vividly brought

home to the

mind of the wayfarer southward bound when he reaches the quaint and

beautiful

old hamlet of Leeds, four miles back from the town of Catskill and upon

the

right bank of the river of that name. The low plain on which Leeds

stands was

once the dwelling-place of a tribe of Algonquin Indians, whose sachems

in 1678

sold it, with the surrounding territory, for four miles in every

direction, to

Marten Van Bergen, justice of the peace and ruling elder in the Dutch

church at

Albany, and Sylvester Salisbury, captain in the British army and

commander of

his majesty's forces upon the Upper Hudson. Neither of these men lived

upon the

estate thus acquired, but their sons, when grown to manhood, took up

their

residence on their patrimony, and the houses which they built thereon

are still

standing, as sound in foundations, walls, and roof-beams as on the day,

now

nearing two centuries agone, when they were finished. At first the younger

Salisbury and Van Bergen dwelt in a wilderness, but in 1732 some eighty

persons

had settled on their lands, and thereafter the village had a slow but

steady

growth. The first care of these settlers, Hollanders and Germans from

the Lower

Palatinate, was to clear out and plant a few acres and to build houses

for

themselves and barns for their cattle. These needful tasks finished,

their

second care was to found a church, of which, in 1753, Dominie Johannes

Schuneman became pastor, ministering faithfully to his flock until his

death

forty years later. Very early in his ministry the dominie won the heart

and

hand of one of the daughters of rich Marten Van Bergen, and the house,

known as

the Parsonage, in which he dwelt with his bride still stands at the

farther

side of a fine old orchard in the outskirts of Leeds. Built of gray

sandstone,

and a story and a half high, a hall on the ground-floor gives access to

two

rooms on one side and to a larger room on the other. The study of the

dominie

was the southeastern room. Here he kept his scanty library, wrote his

sermons,

and received his neighbors when they came to him for friendly gossip or

for

advice. During the Revolution

Dominie Schuneman was an ardent supporter of the patriot cause. Not

content

with preaching from his pulpit the high duty of strenuous defence, lie

became a

member of the local Committee of Safety, and made his house a shelter

for the

soldiers who passed by on their way to the front, and a hospital when

they came

back sick with fever. The worthy man's enthusiasm aroused the wrath of

his Tory

neighbors, who would gladly have set the Mohawks upon him, but lie went

about

armed by day and slept at night with his gun by his side, and so

escaped harm.

Moreover, his congregation were in full sympathy with his high-wrought

patriotism. They were slow-witted men and cautious, but during the

Revolution

their ardor glowed against Great Britain as two hundred years before

that of

their ancestors had glowed against Spain and Alva. One in six of the

men of

Catskill, as Leeds was then called, became soldiers. Some received

commissions

in the New York line; others enlisting as privates, walked with their

muskets

upon their shoulders to Fort George and Stillwater; others became

scouts upon

the Mohawk; and others, through fear of the Iroquois, patrolled the

roads along

the Kaaterskill and in the valley of the Kiskatom. Mention has been made of

the house built by Francis Salisbury in 1705. After his occupancy there

lived

in it a man whose life formed a subject for a romance such as Poe would

have

loved to write. Malevolent and arbitrary, he is said to have so

ill-used a

bound girl in his service that she fled from the old house, aided, it

was

supposed, by her lover, a young Dutch settler. Her master rode into the

mountains in search of her, and discovering her at nightfall, tied her

to the

tail of his horse and started furiously back to Leeds. The horse dashed

the

girl to pieces on the rocks, and her murderer was arrested and brought

to

trial. His family united political influence with great wealth, and

when he was

justly condemned to death they obtained a respite of the sentence. The

curious

decree of the magistrates was that he should be publicly hung in his

ninety-ninth year, and meanwhile he was condemned to wear about his

neck a

halter, that all might know him to be a murderer doomed to death. From

this

time forth the criminal lived in seclusion, rarely coming into the

village,

isolating himself from his fellows, but doggedly wearing his halter,

which on

certain occasions had to be shown in public. When King George ceased to

rule

his American colonies the new order of things seems to have swept into

oblivion

the strange decree of the colonial magistrates, and the hapless owner

of the

Salisbury House was left to die in his bed; but his singular story

affected the

neighborhood, as might be expected, with a belief that the house was

haunted,

and moving tales used to be told of a spectral horse and rider, with

the

shrieking figure of a girl flung from it. Leeds's aged people will tell

you

that in childhood they lived in terror of the spot where the Salisbury

House

stands, firmly believing that its ghostly occupant, with a halter about

his

shrivelled neck, could at any moment appear. In these days, however,

the old house wears a peaceful and sunny look, foreign to all that is

ghostly

and uncanny, yet pleasantly reminiscent of bygone folk and days.

Indeed, in and

all about Leeds time and nature have touched things with a gentle hand,

and the

little village, embosomed by hills and dales, remains an almost perfect

relic

of a past fast becoming too traditional to seem our own. On the other

hand, the

riverside town four miles to the eastward, now called Catskill, but

known in

earlier years as the Strand or the Landing, seems to have forgotten its

plodding and quiet Dutch founders and has become a bustling and

thriving burg,

its only reminders of colonial times being a few olden houses, which

seem to

regard with stately, highbred indifference the activity of the noisy

town that

has grown up around them. None of these fine

specimens of early architecture has a history more romantically

interesting

than a house at the water's edge. It is built of graystone, with a fine

porch

and generous entrance and hallway, and its story begins before the

Revolution,

when Major John Dies, a British officer, married Miss Jane Goelet, and

at the

same time deserted and “fled” to Catskill, where he spent lavish sums

upon the

stone mansion still known as “Dies's Folly.” Tradition has it that in

spite of

his gay and reckless life he lived in constant fear of being arrested

as a

deserter, and at the first appearance of British troops betaking

himself to the

garret, would hide in a hollow of the chimney-stack, whose existence

was known

only to his wife, and to which she brought him food and drink in secret

until

the danger was over. When Madam Dies's father died he left his money in

such a

way that her husband could not squander it, and so after his death the

lady

lived in quiet comfort and much dignity of state, dying at a ripe old

age in

the last years of the last century. Wandering about the fine rooms of

the old

house, it is easy to people it with figures of the dashing major's

period; for

it, like many other famous dwellings in the neighborhood, has suffered

little

from change. The heavy rafters are untouched, walls and windows remain

as of

old, and the house itself, although near the town and the varying

elements of

the shore, seems set in a certain seclusion of its own, and gives a

tinge of

dignity to its surroundings. Yet for the sentimental

pilgrim lingering in Catskill there is a more winsome interest abiding

in a

house which stands on a hilly street about a mile from the village, and

which

was long the home of the most gifted and lovable of our early landscape

painters. It was in a golden, glowing October of the early 20's that

Thomas

Cole, journeying up the Hudson in search of motives for his brush, was

taken

captive by the beauty of the hills and coves of Catskill, and finding a

home

and, later, a wife in the village, lived and worked there until his

death. The

painter's house stands in a garden full of old-fashioned blossoms and

fragrance; its walls of yellow stone show in summer-time against a

gorgeous

garden of hollyhocks; the gateway is overhung with verdure; and below

the

ancient garden-beds are the pine woods reaching down, skirted by farm

lands to

the river. Near the entrance to the upper woods Cole built his first

studio,

where he worked upon the “Course of Empire” and other pictures

belonging to

that period; but nearer to the road stands his latest workshop, where

the busy

hand was arrested midway in his last effort, the “Cross and the World.” Cole, dying at the early

age of forty-seven, rests now in the village cemetery at Catskill, and

in the

old Wilt Wyck burial-ground at Kingston, the next halting-place in our

journey

southward, is the grave of John Vanderlyn, who in his time filled, like

Cole, a

large place in the world of art, and than whom no American painter of

the first

half of the century was the hero of a more brilliant and varied and,

one might

add, more troubled career. A native of Kingston and a protégé of Aaron

Burr,

Vanderlyn was the fellow-student in Rome of Washington Allston; at

Paris in

1808 he carried off the first honors of the Salon, and some of the

figure

pieces which he painted at this period remain the glory of our early

art.

However, his after-career in America, whence he returned in 1815, was a

long

disappointment both to Vanderlyn and his friends, for more tactful men

elbowed

him rudely in an overcrowded field, and neglect and poverty were the

constant

comrades of his last days. Singularly touching, when

it came, was Vanderlyn's end. One morning in September, 1852, he landed

from a

Hudson River steamboat in a feeble condition and set out to walk to

Kingston.

Fatigue quickly overcame him, and he was found sitting by the roadside

by a

friend, from whom he begged a shilling for the transportation of his

trunk,

adding that he was sick and penniless. He secured a small back room at

an inn

in the village, and the friend spoken of went quietly about among a few

of his

acquaintances with a subscription list for the ailing man's

maintenance. Funds

for the purpose were promptly pledged, but they were never needed. A

few

mornings after his arrival Vanderlyn was found dead in bed. Death,

merciful in

its summons to the veteran, had come to him while he slept. Love of his native village

seems to have been Vanderlyn's master passion, and there was reason for

it.

Kingston, with its leaf-embowered streets and its noble old-time air,

is one of

the most beautiful and restful towns along the Hudson. Founded in 1656

by a

band of steadfast and thrifty Hollanders, and called by turns Wilt

Wyck,

Æsopus, and Kingston, the village when Vanderlyn was born in 1776 had

already

taken on the dignity and charm of age. Much of its early history

centres about its

old Dutch church, in the shadow of which Vanderlyn is taking his rest,

and the

records of which, dating back to 1657, give piquant and amusing

glimpses of the

customs, manners, and condition of Kingston's first settlers. When the

church

wanted a bell, the pastor sent word that everybody who had had a child

baptized

at the church should bring a contribution. The congregation brought

offerings

of silver spoons, buttons, buckles, and ornaments of various kinds,

which were

sent to Holland and melted into the present bell that, now attached to

the

clock, strikes the hours from the church steeple. Travelling was a

serious

thing in those days. When Harmanus Meyer, the pastor in 1762, made a

trip to

Albany, fifty miles away, the congregation held a meeting before he

started;

the consistory prepared the form of prayers of the congregation “for

the

special protection of the pastor during his long and perilous journey

to

Albany,” and two elders accompanied him as far as Catskill to protect

him. It

now takes about an hour to go from Kingston to Albany by rail. The building, near the

centre of the town, in which the congregation at present worship is the

fourth

that has stood on the same spot. One of its predecessors was burned by

the

British in 1777, and this fact calls to mind the part played by

Kingston during

the Revolution. There the convention sat which framed the first

constitution of

the State of New York; there the new commonwealth was organized in the

summer

of 1777, and there the first Legislature was in session when Forts

Clinton and

Montgomery fell. When news of that event and the coming of a squadron

under Sir

James Wallace with several thousand soldiers under General Vaughan

reached

Kingston, the members of the Legislature fled. They supposed that the

then

capital of the State would feel most cruelly the strong arm of the

enemy; and

so it did. The British frigates anchored above Kingston Point, and

large

detachments of soldiers marching upon the town, laid nearly every house

in

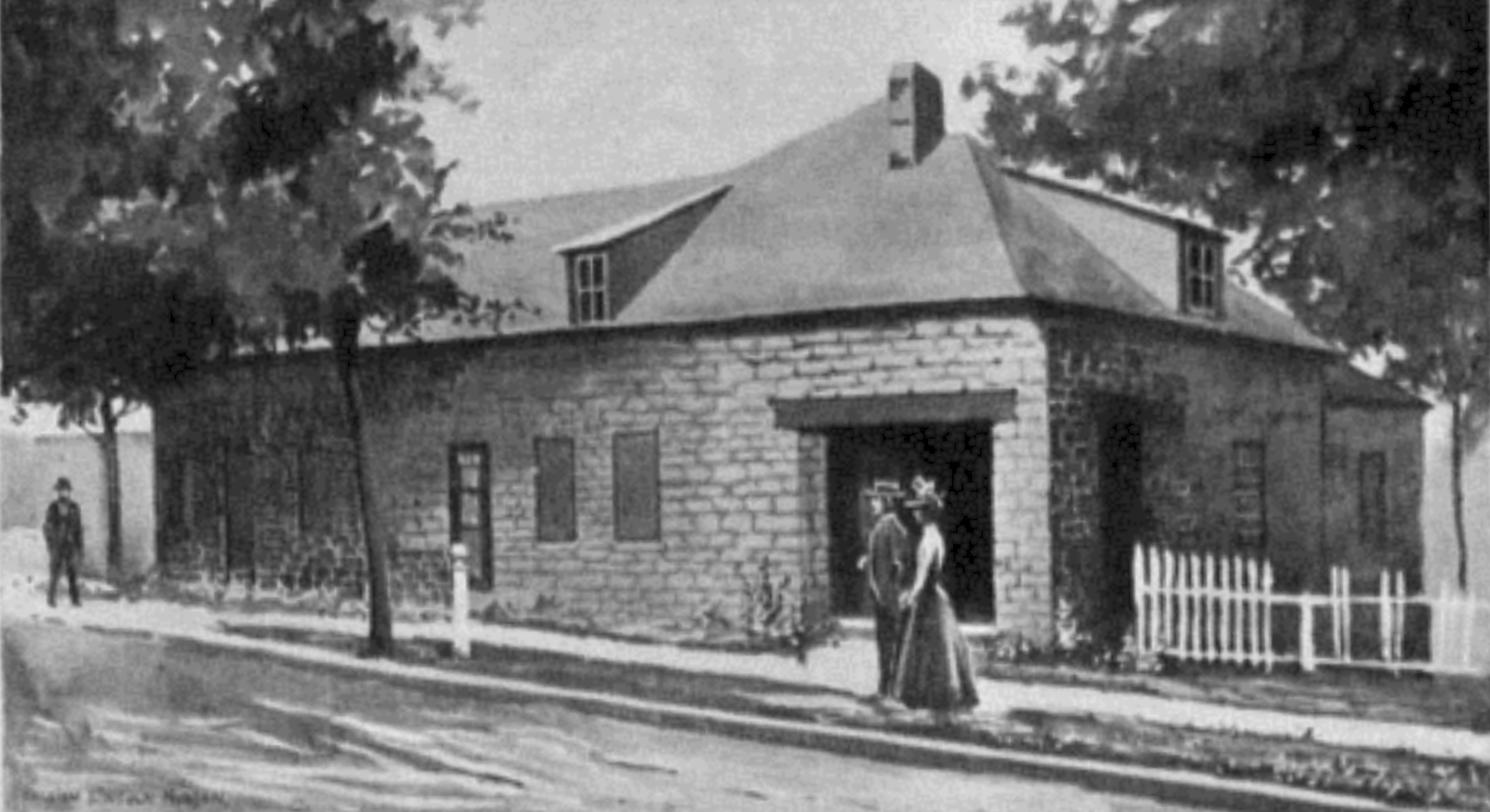

ashes. One of the few buildings

which escaped in part the torch of the British and Tory was the old

Senate

House, now the property of the State. Built in 1676, the Senate House

was

already an old building when the Revolution came. Within its walls John

Jay

drew the draft of the constitution of the State and the Senate for a

time held

its sessions. Partly burned by the troops of General Vaughan, it was

rebuilt

soon afterwards, and occupied for years by men whose names are still

remembered

beyond the confines of their own town. Later still it passed into the

possession of the State, and, carefully restored, now stands as it did

in

former days. Its first owner, Wessel Ten Braeck, was a man of wealth

and

standing, and the house in his time was doubtless considered a building

of the

most aristocratic proportions, being seventy feet long, and having

ceilings two

feet higher than those in most houses of the period. Inside of the old

building, few changes have been made by the restorer, and there is a

delightful

air of antiquity about the rooms. Besides the Senate House, Kingston holds

other interesting relics of the Revolution, and all the way south to

West

Point, by way of Newburgh, New Windsor, and Cornwall, one comes at

every turn

on moving reminders of the great struggle waged nowhere more fiercely

than on

the west bank of the Hudson. As the steamboat approaches the wharf at

Newburgh,

over the broad expanse of the bay of the same name one descries near

the

southern end of the city a low broad-roofed house, built of stone, with

a

flagstaff near, and the grounds around garnished with cannon. That is

the

famous house built by Colonel Hasbrouck in 1750 and occupied as

head-quarters

by Washington during one of the most interesting periods of the war and

at its

close. Then the camp was graced by the presence of Mrs. Washington a

greater

part of the time and the wives of several of the officers, and until a

time

remembered by men not yet old the remains of the borders around the

beds of a

little garden cultivated by Mrs. Washington for amusement might have

been seen

in front of the mansion, which, now the property of the State, is

preserved in

the form it bore when Washington left it.

Old Senate House,

Kingston, New York Interest in the building

centres, perhaps, in the room, with seven doors and one window, used by

the

owner for a parlor and by the commander-in-chief for a dining-room, and

in

which at different times most of the chief officers of the Continental

army,

native and foreign, and many eminent civilians were entertained by

Washington. Half

a century after the Revolution a counterfeit of that room was produced

in

Paris. Lafayette, a short time before his death, was invited, with the

American

minister and several of the latter's countrymen, to a banquet given by

the old

Count de Marbois, secretary to the first French legation in this

country during

the Revolution. At the hour for the repast the company were led to a

room which

contrasted strangely in appearance with the splendors of the mansion

they were

in, — low-boarded, with large projecting beams overhead; a huge

fireplace, with

a broad-throated chimney; a single small uncurtained window, and

numerous small

doors, the whole having the appearance of a Dutch or Belgian kitchen.

Upon a

long rough table was spread a frugal meal, with wine and decanters and

bottles

and glasses and silver goblets, such as indicated the habits of other

times.

“Do you know where we are now?” Marbois asked the marquis and the

American

guests. They paused for a moment, when Lafayette exclaimed, “Ah! the

seven doors

and one window, and the silver camp goblets, such as the marshals of

France

used in my youth. We are at Washington's head-quarters on the Hudson,

fifty

years ago!” The room thus vividly

recalled by Lafayette has, as I have stated, seven doors. The one on

the

northeast gives access to the former bedroom of Washington; a small

room

adjoining was his office, and is historic, because at a little desk

here, in

May, 1782, he wrote the letter declining the crown some of his field

officers

had planned to confer upon him, the masterly address to his disaffected

officers, and finally the pæan of joy and thanksgiving that announced

to the

army the return of peace. On the west is a door opening into a

moderate-sized

hall, in which is a stairway leading to the chambers above, and an

outer door

opening on the grounds on the west. On the south and southwest are

doors giving

access to the apartments occupied by the Hasbrouck family, and which

were in no

way connected with Washington's occupancy. The parlor in which Madam

Washington

received her guests was the northwest room, adjoining the office, and

opening

into the hall before mentioned. Following the acquisition

of the headquarters by the State in 1849, citizens of Newburgh and its

vicinity

began forming here a museum of Revolutionary relics, which in the

process of

time has become one of the most interesting collections of its kind in

existence. The old arm-chair of Washington has resumed its former post

in his

bedroom; portraits of General and Madam Washington and of Lafayette

hang on the

walls of the former office; the watch with which Madam Washington timed

the

coming of her guests is one of the trophies of the dining-room; so also

is the

battered copper tea-kettle in the fireplace, which once formed a part

of the

camp equipage of Lafayette; Aaron Burr's sword hangs in its iron

scabbard in

the southeast room; while a collection of several hundred letters and

private

papers reveals to the student the whole minutiæ of the Revolution and

acquaints

him with the secret thoughts and purposes of its leaders. The printed catalogue of

the collection enumerates upward of eight hundred articles. To the

lover of

Washington the most impressive of these are the letters and papers

dealing with

what is known as the Gates conspiracy, in the suppression of which the

patriot

commander gave shining proof of his almost perfect mastery of men. When

the

Continental army was about to be disbanded in the spring of 1783 Gates

and a

few other officers had inflammatory appeals distributed among the

troops urging

them to demand their pay and get it or overthrow the government. They

had fixed

a date for a convention of the disaffected elements, and the danger was

serious. The convention was largely

attended, and Gates was chosen as its chairman. Before the proceedings

had gone

far Washington entered, unattended and unannounced, his face wearing a

sad and

troubled look. He began a short speech, admitting the justice of their

claims,

and expressing deep sympathy for their sufferings, but appealed to them

not to

desert their country's cause after covering themselves with scars in

its

defence; and, above all, not to become the dupes of British intrigues,

as the

appeals that had aroused them had doubtless been the work of crafty

emissaries

of England, “eager to disgrace the army they had not been able to

vanquish.” He

assured them that Congress would do them justice, and took from his

pocket a

letter to sustain this assurance, which he attempted to read, but could

not

without putting on his glasses. Slowly raising them, he said, with

quiet

pathos, “My brothers, I have grown gray in your service, and now I find

myself

becoming blind.” At the conclusion he walked slowly out, but there was

no more

of the meeting. Those who remained did so only to pass a resolution

professing

implicit faith in Congress and loyalty to their country. A few weeks after this

incident just related, on April 19, 1783, came the last event of

importance in

the history of the patriot camp at Newburgh, — the publishing of the

proclamation of Congress announcing the cessation of hostilities.

Washington

had been in receipt of news of peace for some days, but hesitated to

publish it

to the army lest the troops who had enlisted for the war should

consider their

engagement filled and demand a discharge. But on the 18th, unable

longer to

conceal the good news, he issued his orders, directing that the

proclamation of

Congress should be published on the 19th, in the presence of the

several

brigades. By a happy coincidence it was the anniversary of the battle

of

Lexington, fought eight years before. When the day arrived, it was

ushered in

by salvoes of artillery, and at noon the nine brigades of the army,

drawn up on

dress parade, received from the lips of their commander-in-chief the

news of

the war's termination. This gathering, however, was but the precursor

of a

grand jubilee in honor of peace, which occurred some days later, and

which was

celebrated by the entire army at Newburgh, Fishkill, West Point, and at

all the

scattered outposts farther down the river. Early in June the army was

removed

to West Point, and there, and not at Newburgh, Washington's Farewell

Address

was read and the war-worn ranks formally disbanded. Cornwall, four miles below

Newburgh, is a growth of the present century, but New Windsor, lying

between

them, was long the head-quarters of Generals Knox and Greene, and

Cornwall

itself borrows a lively interest for the wanderer from the fact that it

is closely

associated with the closing years of Nathaniel Parker Willis. The house

to which

he gave the name of Idlewild stands a little way from the village, and

is still

green to the memory of the poet. Since Willis's death the place has

passed in

turn into various hands, until now it is the home of a wealthy New York

business man. Here and there in the

grounds remains a suggestion of the times of Willis. The pine drive

leading to

the house, along which the greatest literary lights of the

Knickerbocker period

passed during its palmy days, still remains intact, the dense growth of

the

trees only making the road the more picturesque, and the brook by which

Willis

often sat still runs on through the grounds as of yore, but in the

house

everything is remodelled and modernized. The room from whose windows

Willis was

wont to look over the Hudson, and where he did most of his charming

writing, is

now a bedchamber modern in its every appointment and suggesting its age

only by

the high ceiling and curious mantel. Cornwall has other

literary memories than those associated with Willis. Only a few city

blocks

from Idlewild is the house in which Edward Payson Roe lived and wrote

his books

and passed away, and the novelist's grave is in the little Presbyterian

cemetery of the village, close to the bank of the Hudson, — a spot of

exceeding

beauty and just the niche in a noble country where a lover of nature

should

take his rest. Everything about the plot proves that the place is not

forgotten. A large block of granite marks the burial-place of the

romancer,

while on it his name is carved twice, the first, “Edward Payson Roe,”

as a

family record, while the second, “E. P. Roe,” at the base of the stone,

indicates the public man. Journeying southward from

Cornwall, as the boat nears West Point one descries, in a house set on

a rocky

promontory jutting out from the bank of the river, another of the

literary

landmarks of the Hudson. In this house, a low, straggling structure

with tiny

windows and tinier panes of glass, which tell, even at a distance, of

colonial

times, Susan Warner lived and did her literary work, work which for the

time

being made her name a household word throughout the length and breadth

of the

land. Few women were more popular in her time, and yet to-day the

author of

“The Wide, Wide World” is almost forgotten. I thought of this as I

stood beside

her grave. It is in the military cemetery, close by the Cadet's

monument, where

she was buried in the spot she herself selected. The grave is kept

abloom by

the sister of the authoress, Anna Warner, herself a writer. A close

affection

existed between the Warner sisters, and it is the fragrance of this,

and almost

only this, that indicates to the visitor at the West Point grave that

the

author of some of the best-known novels ever written has not entirely

passed

from memory. Yet in and about West

Point there are not wanting a hundred proofs that the dead are not

forgotten.

Crowning the summit of Mount Independence, nature's guardian of our

national

military school, are the gray ruins of Fort Putnam, built under the

direction

of Kosciusko, and during the Revolution the most important of the

military

works along the Hudson. On the extremity of the promontory of West

Point are

the ruins of Fort Clinton, now sheltering a monument to the memory of

Kosciusko; and plainly visible a little way to the northward is the

former site

of Fort Montgomery, and on a plateau directly across the river stands

the

Beverley Robinson House, in which Benedict Arnold planned the betrayal

of his

country. Forts Clinton and

Montgomery and the intervening ground were the theatre of one of the

most

fiercely contested conflicts of the Revolution. The forts were built to

defend

the entrance to the Highlands against fleets of the enemy that might

ascend the

river, for it was known from the beginning that it was the purpose of

the

British to get possession, if possible, of the valley of the Hudson,

and so

separate New England from the other colonies. In addition to these

forts, a

boom and chain were stretched across the river from Fort Montgomery to

Anthony's Nose to obstruct navigation. On the 7th of October, 1777, the

British

general Clinton swept around the towering Donderberg with a part of his

army

and fell upon the forts, where George and James Clinton commanded the

little

garrisons. It was not an easy task

for the enemy to approach the forts through the rugged mountain passes.

They

had divided, one party, accompanied by Clinton, making their way

towards

evening between Lake Sinnipink, in the rear of the lower fort, and the

river.

There they encountered abatis covering a detachment of Americans, and a

severe

fight ensued, after which both divisions pressed towards the forts and

closely

invested them, being supported by a heavy cannonade from the British

flotilla.

The battle raged until nightfall, but finally overwhelming numbers

caused the

Americans to abandon their works and flee to the mountains. The

conflict ended

in the breaking of the boom and chain, and the passage up the river of

a

British squadron with marauding troops, who laid in ashes many a fair

homestead

belonging to patriots as far north as Livingston's manor, on the lower

verge of

Columbia County. Twelve miles south of West

Point the steamboat comes abreast of another stirring Revolutionary

landmark, a

rocky height advancing far into the river and known as Stony Point. Its

capture

on the 16th of July, 1779, was one of the most brilliant incidents in

the

brilliant career of “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Following the loss of Forts

Montgomery

and Clinton, Washington had projected two works, at Stony Point and

Verplanck's

Point, as outworks of the mountain passes above. A small but strong

fort had

been erected at Verplanck's Point and garrisoned by seventy men, and a

more

important work was in progress at Stony Point when the British, under

Clinton,

advanced up the Hudson; the men in the unfinished fort abandoned it on

the

approach of the enemy, and the latter took possession. The garrison on

the

eastern bank at the same time surrendered to General Vaughan. Sir Henry

stationed garrisons in both posts and completed the fortifications at

Stony Point. The chances for success in

a night assault upon the Point were talked over at the headquarters of

Washington at West Point. General Wayne was then in command of troops

in that

vicinity. “Can you take the fort by assault?” Washington asked Wayne.

“I'll storm

hell, general, if you'll plan it!” was the prompt reply. Washington

smiled, and

bade him attempt the recapture of the Point, which the British had

garrisoned

with six hundred men and crowned with strong works, furnished with

heavy

ordnance, commanding the morass and causeway that connected the Point

with the

mainland. On the night of July 15,

1779, a negro of the neighborhood guided Wayne and his men to the

Point, and by

giving the countersign to the sentinel they were enabled to cross the

causeway

without alarm. At the foot of the promontory the troops were divided

into two

columns, for simultaneous attacks on opposite sides of the works. The

Americans

were close upon the outworks before they were discovered; there was

then severe

skirmishing at the pickets. The Americans used only

the bayonet, the others discharged their muskets. The reports roused

the

garrison, and Stony Point was instantly in an uproar. Notwithstanding a

tremendous fire of grape-shot and musketry on the assailants, the two

columns forced

their way with the bayonet. Colonel Fleury entered the fort and struck

the

British flag. Major Posey sprang to the ramparts and shouted, “The fort

is our

own!” Wayne had received a contusion on the head from a musket-ball,

and

believing it was a death-wound, begged his aides to carry him into the

fort

that he might die at the head of his column, but he soon recovered his

self-possession. The two columns arrived nearly at the same time, met

at the

centre of the works, and the garrison surrendered at discretion. The

American

loss was less than a hundred killed and wounded, while of the British

more than

six times that number were slain and taken prisoners. With Stony Point left

astern, the boat enters the broad expanse of Haverstraw Bay, and

touches at the

town of the same name, whence a road passes among the hills to the

village of

Tappan, near which André was tried and executed, and which we had

planned to

make the last halt in our journey down the west bank of the Hudson. It

was the

second day after his ill-timed meeting with Arnold at Haverstraw, to

arrange for

the surrender of West Point, that André, hurrying southward to New

York, was

arrested near Tarrytown, and without delay conveyed to Tappan, the

head-quarters of the American army. Here, Arnold having meanwhile fled

to the

British camp, André was tried, condemned as a spy, and two days later

put to

death. The old graystone Dutch farm-house then used as a prison, in

which he

passed the last days of his short life, still stands in the outskirts

of Tappan,

and has lately been restored to its original form. The room in which

André

spent his waking hours and was visited by Alexander Hamilton and others

is in

the front of the house. Back of it is a smaller apartment in which he

slept,

and which has a window looking out to the west, where, tradition has

it, he saw

them rear the scaffold for his execution. From the house a gentle slope

carries

one up the hill, where André was hanged at mid-day of October 2, 1780,

“reconciled to death, but detesting its mode,” and begging those

present “to

bear witness that he met his death like a brave man.” His body was

buried at

the foot of the gallows, where it lay until 1821, when, by order of the

Duke of

York, the British consul at New York caused it to be disinterred and

sent to

England for final burial near a mural monument which George III. had

erected to

his memory in Westminster Abbey. Americans, generous always

in their sympathy for the unfortunate, have never forgotten André's

dying

request. He should have been left to sleep undisturbed in the spot

where kindly

nature had already claimed him for her own. END OF VOL. I. |