| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

I TWO ATLANTIC ISLANDS It is only a short hour's

sail from Greenport on the mainland to the sea-girt domain

of Gardiner's

Island, set down, like a giant emerald on a woman's breast,

in the centre of

the wide bay that cuts deep into Long Island's eastern end,

yet the journey

carries one into another world, for Gardiner's Island was

the first founded of

the manors of colonial New York, and is the only one of them

that has remained

intact down to the present time. Not a foot of its soil has

ever been owned by

any save a Gardiner since it first passed from the

possession of the Indians in

1639, nor have time and the years served to impair its

quietude and seclusion.

It still lies completely undisturbed in the busy track of

commerce, a land

quite out of reach of those modern aids to restlessness, the

newspaper, the

mail-bag, the railroad, the telegraph, and the hotel, where

one is as

completely severed from the rush and clamor of the thing men

call civilization

as one would be in mid-ocean, while wood and field and

century-old manor-house

peering out from its cosy nook, each helps to heighten the

illusion of age and

distance which the island imparts to the visitor, and makes

potent and real the

pleasing fancy that chance has wafted him for the moment to

some placid feudal

stronghold of the past. A resolute, sturdy figure

seen through the murk and mist of two hundred and sixty

years is that of

doughty Lion Gardiner, the first English settler in the

province of New York

and first lord of the manor of Gardiner's Island. The name

of Lion well became

this hardy warrior, whose fighting days began in the time of

the first Charles,

when he went from England to Holland to serve as lieutenant

with the English

allies under Lord Vere. There he married a Dutch lady, Mary

Willemson, daughter

of a “deurcant” in the town of Waerden, and became, so he

tells us, “an

engineer and master of works of fortification in the legions

of the Prince of

Orange, in the Low Countries.” Gardiner might have lived

out his days in Holland, but being a friend of the Puritans

and of the

Parliament, he was engaged in 1635 by Lord Say and Seal,

with other nobles and

gentry, to go to the new plantation of Connecticut, under

John Winthrop, the

younger, and to build a fort at the mouth of the river. With

his wife he set

sail in the “Bachelor,” a barque of twenty-five tons burden,

and was three

months and ten days on the voyage from Gravesend to Boston,

where he was

induced to stay long enough to take charge of and complete

the military works

on Fort Hill, — those that Jocelyn described later on as

mounted with “loud

babbling guns.” Arrived at the mouth of

the Connecticut, Gardiner proceeded to construct, amid the

greatest difficulties,

and with only a few men to aid him, a strong fort of hewn

timber, — with ditch,

drawbridge, palisade, and rampart, — to which he gave the

name of Saybrook.

This was the first stronghold erected in New England outside

of Boston, and

there Gardiner dwelt as commander for four years, years of

ceaseless labor, of

constant anxiety, of ever-present danger, and of active

warfare with the

Pequots, — Gardiner himself was severely wounded in one

close encounter, — diversified

by efforts to strengthen the plantation and agriculture

carried on under the

enemy's fire. Most men at the end of

four years of this sort of hardship would have gladly sought

a more peaceful

pursuit in life's crowded places, — not so with Gardiner,

for, when his

engagement expired with the lords and gentlemen in whose

employ he had come to

America, he plunged still farther into the wilderness,

purchasing from the

Paumanoc Indians, for “ten coats of trading cloath,”

Manchonake, or the Isle of

Wight, now Gardiner's Island, sixteen miles distant by water

from the nearest

settlement of English at Saybrook. The Indians were

Gardiner's only neighbors in his new home, but, despite the

fact that he had

been the chief author of the plans which in 1637 resulted in

the defeat and

almost complete annihilation of the Pequots, he knew how to

foster and maintain

peaceful relations with the red men. Before going to his

island he won the good

will of Wyandance, later chief of the Montauks, and the

friendship between

them, which ended only with the Indian's death, furnishes

the material for one

of the noblest chapters in colonial history. Twice Gardiner foiled

conspiracies for a general onslaught on the English by means

of the warnings

which his firm friend gave him; another time he remained as

hostage with the

Indians while Wyandance went before the English magistrates,

who had demanded

that he should discover and give up certain murderers, while

on still another

occasion, when Ninignet, chief of the Narragansetts, seized

and carried off the

daughter of Wyandance, on the night of her wedding, Gardiner

succeeded in

ransoming and restoring her to the father. The sachem

rewarded this last act of

friendship by the gift to Gardiner of a large tract of land

on the north shore

of Long Island, and when he died left his son to the

guardianship of Lion and

his son David. Indeed, a singularly beneficent one was this

friendship between

the white man and the red. They acted in concert with entire

mutual trust,

keeping the Long Island tribes on peaceful terms with the

English by swift and

severe measures in case of wrong-doing, tempered with

diplomacy and with

justice to both sides. For thirteen years

Gardiner remained on the island which bears his name. Here

he exerted his good

influence unmolested by the savages about him, at the same

time developing his

territory and deriving an income from the off-shore

whale-fishery, which then

flourished about the eastern end of Long Island. In 1653,

leaving the island to

the care of the old soldiers whom he had brought from the

fort as farmers, he

took up his residence in East Hampton, where he had bought

much land and where

he died in 1663, at the age of sixty-four. No one knows the

place of his

sepulture, but in the older East Hampton Cemetery, among the

graves of many

Gardiners, may be seen two very ancient flat posts of “drift

cedar” sunk deep

in the soil and joined together by a rail of the same

material, about the

normal length of a man. Under this rude memorial, it has

been surmised, rests

the body of Lion Gardiner. When the time comes to rear a

monument to the ideal

First Settler here is the spot where it should be placed. When Lion Gardiner died

his island passed to his wife, who at her death left it to

their son David “in

tail” to his first male heir, and the first heirs male

following, forever.

David, in leaving it to his eldest son, reexpressed the

entail, and the estate

descended from father to son for more than a hundred and

fifty years until, in

1829, by the death of the eighth proprietor without issue,

it passed to his

younger brother, in the hands of whose descendants it has

ever since remained. Lion Gardiner's title to

the island derived from the Indians was confirmed by a grant

from the agent of

the Earl of Stirling, who held a royal patent for an immense

slice of

territory, in which the island was embraced, — a grant which

allowed Gardiner

to make and execute such laws as he pleased for church and

civil government on

his own land, if according to God and the king, “without

giving any account

thereof to any one whomsoever;” and David Gardiner, although

he duly and

formally acknowledged his submission to New York, received

from Governor

Nicholls a renewal of these privileges, the consideration

being five pounds in

hand and a yearly rental to the same amount. Each royal

governor who came out

to New York after Nicholls's day levied a charge of five

pounds for issuing a

new patent confirming the older ones, but in 1686 Governor

Dongan, for a

handsome sum paid down, gave David Gardiner a patent which

created the island a

lordship and manor, agreeing that the king would thenceforth

accept, in lieu of

all other tribute, one ewe lamb on the first of May in each

year. John Gardiner, third lord

of the island, aside from several memorable visits from

Captain Kidd, of which

more in another place, was much annoyed by pirates, and

occasionally fared

badly at their hands. Twice they ransacked his house,

carrying off his plate

and cattle, and once they beat him with swords and tied him

to a tree, while

they searched for the money which they believed he had

concealed somewhere

about the manor. Then for a long time Gardiner's Island was

a country without a

history, but in the first year of the Revolution it was

plundered by the

British of its droves of cattle and sheep, which went to

feed the troops of

General Gage encamped at Boston; a patriot committee seized

the rest of the

stock, paying for it in Continental money, and the officers

and men of the

royal fleet, which during the winter of 1781 lay at anchor

in the neighboring

bay, plundered and marauded so effectively that when the war

ended there

remained on the island hardly enough personal property to

pay arrears of taxes.

However, John Lyon Gardiner, seventh proprietor and an able

man of affairs,

held the estate together and restored its prosperity, and

ever since his death

its history has been one of peace and contentment. Time was

when the lords of

the island derived a considerable revenue from whaling and

the culture of

maize, but in later years the estate has been devoted to

farming, sheep-raising,

and stock-breeding, the sea being resorted to only for such

fish, clams, and

lobsters as may supply the daily needs of the inhabitants. Seen from the sea, the

island, seven miles long, from one to two wide, and

enclosing three thousand

good acres, has no doubt changed but little since the

long-gone day when Lion

Gardiner came from Saybrook fort to build his home there.

The nearest land is

three miles and a half distant, at Fireplace, so named

because in other times

strangers bound for the manor used to build a fire of

sea-weed on the sand, the

smoke of which being seen across the three-mile channel, a

skiff would be sent

over for the visitors. Shelter Island on the west, and the

north and south arms

of Long Island, help to convert Gardiner's Bay into a

spacious roadstead,

where, as I have said, a British fleet lay anchored during a

portion of the

Revolutionary War; but from the high bluffs which flank the

eastern end of the

island one gazes out over the open Atlantic until the

blending of sea and sky

blocks the range of vision. The landing-place is on

the sheltered southwest side of the island. Close at hand is

an ancient

windmill that supplies the inhabitants with flour, and a

little farther back

from the sea is the roomy manor-house, built in 1774 and

with moss-covered

dormer roof, behind which green, rolling downs stretch away

to the noble woods

which cover the northern and western parts of the island.

Very near the centre

of the island, its white headstones grouped about a giant

granite boulder,

stands the graveyard of the Gardiners, and the other half of

the estate is

given over to woods, orchards, and wide-reaching fields of

grain. Save the

keeper of the federal light-house at the northern end of the

island, all the

persons living thereon, some sixty in number, are servants

and tenants of the

proprietor, or members of his family, for the kindly,

patriarchal system

instituted by stout old Lion Gardiner has continued until

the present day, with

results that a king or sage might envy. Indeed, one finds

Gardiner's Island a

little principality where a good citizen rules without pomp,

guided only by the

dictates of justice and good sense, where crime and violence

are unknown, and

where diligence, order, and contentment hold benignant sway

from one year's end

to another. There is not even a watch-dog on the place, and

one is not

surprised to learn that the turbulent characters who now and

then drift thither

among the hired summer laborers promptly grow calm under the

softening

influence of the sweet and noble landscape, the grateful

ocean air, and the

time-haloed quietude that invest the daily routine of this

ocean retreat. Only restless wraiths from out

the past

now disturb the peace and quiet of Gardiner's Island. One of

these is the

uneasy memory of Captain Kidd, honest master mariner turned

pirate, of whom so

much that is misleading, so little that has a basis of

truth, has been

published. It was in the closing days of June, 1699, that

Kidd, returning from

the three years' cruise that had caused a price to be set on

his head, and

later led to his trial and execution in London, — sent out

to cruise against

pirates he had ended by adopting the trade of his victims, —

cast anchor in

Gardiner's Bay. When his sloop, which carried six guns, had

lain two days in

sight of the island, without making any sign, Lord John

Gardiner put off in a

boat to board her and inquire what she was. Captain Kidd,

whom he had never met

before, received Lord John politely, and in answer to his

inquiries said he was

going to Boston to see Lord Bellomont, then governor of the

provinces of New

York and Massachusetts, and one of the company which had

embarked Kidd on his

pirate-quest. Meanwhile he wished Gardiner to take two negro

boys and a negro

girl and keep them until he came or sent for them.

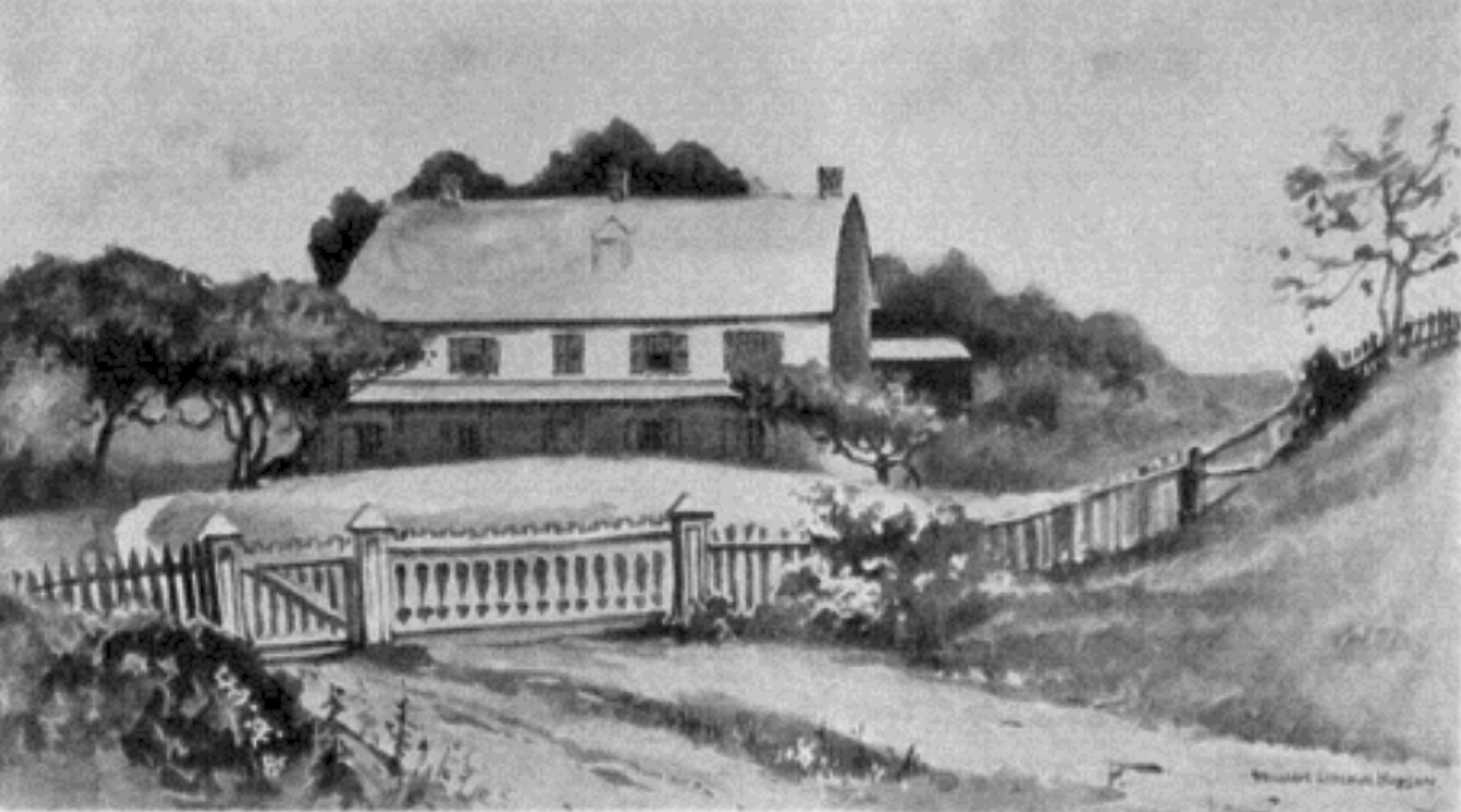

Manor

House, Gardiner's Island,

New York The next day Kidd demanded

from Lord John a tribute of six sheep and a barrel of cider,

which was

cheerfully rendered. The captain, however, gave Gardiner two

pieces of costly

Bengal muslin for his wife, handed Gardiner's men four

pieces of gold for their

trouble, and offered to pay for the cider. Some of Kidd's

crew also presented

the island men with muslin for neckcloths. After this

exchange of civilities

the rover fired a salute of four guns and stood for Block

Island, some twenty

miles away. Three days later Kidd came back to the manor

island, and, sending

one of his followers to fetch Gardiner, commanded the latter

to take and keep

for him or order a chest and a box of gold, a bundle of

quilts, and four bales

of goods. The chests were buried in a swamp near the

manor-house, and Kidd,

with a timely touch of ferocity, told Lord John that if he

called for the

treasure and it were missing he would take his or his son's

head. Before

departing, however, the pirate leader presented his host

with a bag of sugar.

It was on this occasion, also, that Kidd requested Mrs.

Gardiner to roast a pig

for him, and was so pleased with the result that he gave her

a piece of cloth

of gold, a fragment of which is still preserved at the

manor. Then Kidd set sail for

Boston. A week or so later he was arrested in that city, and

Lord John, ordered

by the authorities to render up the goods in his charge,

made haste to obey

their command. In the treasure which Gardiner in due time

turned over to Lord

Bellomont there were bags of coined gold and silver, a bag

of silver rings and

unpolished gems, agates, amethysts, bags containing silver

buttons and lamps,

broken silver, gold bars and silver bars, and sixty-nine

precious stones “by

tale.” However, the only profit derived by Lord John —

history, let it be said

in passing, tells us that “he had so much ability in affairs

that, although he

married four times and spent a great deal of money, he gave

handsome dowries to

his daughters and left a large estate at his death” — from

his relations with

Kidd was accidental. On coming home from Boston, whither he

had gone to deliver

the treasure to Lord Bellomont, he unpacked his portmanteau,

in which some of

the smaller packages had been stowed, and as he did so there

rolled out upon

the floor a diamond that had got astray from the “precious

stones by tale.” He

would have sent it after the rest, but his wife interposed;

she thought he had

been at pains enough, and on her own responsibility kept the

diamond. Yet even

this slight guerdon slipped away, after the manner of all

magic or underhand

wealth. Mrs. Gardiner gave it to her daughter, and Lord John

at that time kept

a chaplain, one Thomas Green, of Boston, in whom his

daughter became

interested. Lord John kept the

chaplain; the chaplain ran away with and married the

daughter; and the daughter

kept the diamond. From this union of maid

and parson sprang the famous Gardiner-Gard of Boston, the

first of whom married

a daughter of the artist Copley, sister of Baron Lyndhurst,

Lord Chancellor of

England. Other family connections of the Gardiners have

historic interest. A

son of one of the proprietors married the daughter of Sir

Richard Saltonstall;

a daughter of another was the great-grandmother of George

Bancroft; and the

widow of a third found a second husband in General Israel

Putnam, and died at

his head-quarters in the Hudson Highlands during the

Revolution. It should be

said here, too, that Mary, the daughter of Lion, married

Jeremiah, the ancestor

of Roscoe Conkling, while in 1844 Miss Juliana Gardiner

became the second wife

of President Tyler, — thus firmly has the family tree of the

Saybrook captain

taken root in New World soil. When Captain William Kidd

during the eventful voyage that proved his last took his

leave of Lord John

Gardiner's sea-girt domain he headed his course for Block

Island, twenty miles

to the eastward. We followed in his trail one cloud-free,

wind-swept summer

morning, and an hour or so after leaving Gardiner's Bay

there arose from the

sea ahead of us of what seemed like a dark, purple cloud

thrust athwart the

southern horizon line. Then, as the trim sloop yacht kept on

its way, the cloud

changed in hue to a brilliant green, flecked here and there

with brown, and its

misty prominences multiplying into a hundred conical little

hills, their smooth

flanks covered with stone-walled farms, strewn with white

homesteads and

animated with flocks of sheep, cattle, and fowl, Block

Island sprang smiling

from the waves to greet us. We landed at a granite

breakwater, which provides the only haven of the island, and

before a week had

ended had explored it from end to end. Its territory extends

ten miles from

east to west, and six miles from north to south in its

widest place, having

nearly the shape of a pear. Thickly wooded in the old Indian

days, the land is

now barren of anything in the shape of trees, save a few

pinched and starveling

poplars set out around some of the dwellings as a protection

from the winds.

Ponds are everywhere, several of considerable size, and a

host of smaller ones

lying in the hollows between the hills, and in many

instances white with pond

lilies, remarkable for their size and beauty. These ponds

are set between

knolls, and every knoll is capped with a small, one-story

farm-house, with

stone chimney and sharp roof sloping to the ground, its

shingled walls thickly

coated with whitewash, the only wash that, I am told, will

stand the intensely

vaporous air of the island. Some of these dwellings are

older than the century,

and the island's solitary windmill was built of lumber grown

two hundred years

ago. From the hills inside the wind-stained sails of this

mill, the spires of

two tiny churches, and the white towers of five

school-houses stand out against

the sky line. On the southeast side of

the island, rising one hundred and twenty feet from the

water, stands Mohegan

Bluff, on which a light-house was built some twenty years

ago. Within the great

lantern, which rises two hundred and four feet from the sea,

four or five

people can stand together, its light on a clear night being

visible for

twenty-one nautical miles; and those who are fond of figures

will, perhaps, be

interested in the keeper's statement, made with every

evidence of pride, that

it takes twelve hundred gallons of oil annually to feed the

hungry wick. To

further aid the storm-beset mariner, a mighty foghorn,

operated by a

steam-engine of five- or six-horse power, has been set up

near the light-house,

and there are also three life-saving stations on the island,

all of which,

unhappily, find plenty of work to do in the winter months,

as the south shore

is rocky and dangerous; the island lies in the track of all

east and west-bound

vessels, and the wind forever howls and whistles across it

with formidable

volume and force. In the summer this is pleasant enough, but

in winter death

often follows in the wind's wake, and only the silent rocks,

worn and scarred

with the débris of wrecked vessels, know how many poor

sailors have perished on

this perilous coast. Block Island — the Indian

name was Manisees, meaning Little God's Island — antedates

Plymouth Rock in

point of history by nearly a century, it having been first

brought to Old World

notice in 1524 by Verrazani, a French navigator. The present

name, however, is

derived from the Dutch explorer Adrian Block, who visited

the island some

ninety years later, and whose sailors were, doubtless, the

first white men to

land on its shores. The Narragansett, Pequot, and Mohegan

Indians lived here at

different times, and were constantly involved in broils

about the ownership of

the island, which for the murder, in 1636, of one Captain

John Oldham, a Boston

trader, was subjugated by the colony of Massachusetts. Some

years later it was

transferred to John Endicott and three associates, who in

turn sold it to

sixteen individuals for four hundred pounds. This party soon

settled in their

newly-acquired territory, and their descendants now form a

large portion of the

inhabitants of the island. Nicholas Ball, who died some

years ago, and who for

more than a generation was the most influential man on the

island, was a direct

descendant in the sixth generation from one of these

original settlers. Once settled, the island

throve apace, and during the wars between France and England

its fertile farms

and fat herds and flocks furnished tempting and convenient

prey for marauders

and pirates, who repeatedly descended on its shores and

carried off or

destroyed everything on which they could lay their hands.

Although protection

was asked of the General Assembly of Rhode Island by the

inhabitants it was

never given them. The General Assembly, if the truth was

known, probably had

all it could do to protect itself, and its wards had to

defend themselves as

best they could. However, the town records of this little

forsaken,

war-pillaged island show a strong love of freedom and of

democratic

institutions, and when the Revolutionary War came on its

inhabitants gave

splendid proof of the sturdy stuff that was in them, placing

their lives and

property and honor upon the altar of their country as freely

as the people of

the colonies, but faring worst of all. At first they were

thoroughly sacked by

their mother colony, and then left to the tender mercies of

hostile British

ships, while to make their plight still worse, they were

forbidden by an

enactment to visit the mainland, unless they intended to

settle there, and it

seemed that every man's hand was against them. But with

peace came independence

and prosperity in its train, and in these latter days the

island's most

dangerous visitor is the vagrom summer tourist. Farming and fishing were

long the only, and still remain the chief, vocations of the

inhabitants of the

island. Bluefish, codfish, swordfish, sharks, whales, and

many other kinds of

fish are caught here in their season, and the annual value

of the island

fisheries is something like one hundred thousand dollars.

The typical Block

Island fishing-boat, which was originated by the islanders

more than two

hundred years ago and is known in local parlance as a

double-ender, is a very

queer craft, — a huge canoe, wide open like a caravel, with

sides fabricated of

long strips of sheeting, overlapping each other like

clapboards on a house,

sharp at both ends, so that a landsman is never quite sure

which is stern and which

bow, and with a tall mast stepped almost in the middle of

the keel. It is never

larger than a medium-sized sloop yacht; yet with one great

square-sail a crew

of rugged Block Islanders do not hesitate to drive one of

these odd craft in

the thickest weather to Newfoundland, or across the ocean

for that matter. In the hands of other

mariners, however, the double-ender is a most refractory,

disobedient, and

insurrectionary craft, likely to spill them without warning,

after the manner

of a bucking broncho, or to go ashore in spite of tiller and

sail, and in

defiance of all well-grounded principles of navigation. A

genuine islander can

do pretty nearly what he pleases with it, sail into the very

eye of the wind

without winking, cruise right over sand spits and bars not

too far out of

water, so light is the boat's draught; and there is a

trustworthy tradition

that once an islander, alone in his open boat, with only his

dinner-pail full

of provision, was blown out to sea in a storm, and a few

days later drove tranquilly

into Havana. He devoted a week to sight-seeing in the Cuban

city, then

provisioned his craft anew, and set sail for the American

republic — at large.

Unfortunately, in the hurricane he had lost his compass

overboard, and most of

his other implements useful in seafaring, and had no money

to purchase new

ones. A sympathetic Spaniard in Havana was anxious to know

how on earth he

expected he would ever be able to get back to America and

Block Island with no

compass, only a part of his rudder and sail, and with

various other things

lacking that are generally thought to be indispensable in

navigation. “Oh,” was

the matter-of-fact reply of the undaunted skipper, “I am

just a-going to steer

nor'nor'west, and with fair weather and time, barring

accidents, I reckon I can

hit the broadside of the United States somewheres.” In about

three weeks he did

hit it, and no one wondered at the exploit who was

acquainted with the sturdy,

sea-going capabilities of the double-ender and Block Island

skipper. When the viking boat,

shown afterwards at the World's Fair, visited the harbor of

New London in the

summer of 1893, a Block Island skipper who chanced to be in

the Connecticut

town at that time was surprised and greatly pleased with the

appearance of the

northman. As a matter of fact, barring out her dragon-head

prow, she was very

like a Block Island double-ender, and local wiseacres affirm

that the model of

the old-time viking boat was familiar to the forefathers of

the men who settled

Block Island; that they bequeathed it to their descendants,

and that some of

the latter having brought the substantial features of it as

a part of their

nautical knowledge across the Atlantic, have preserved and

perpetuated them in

the New World in the double-end craft centuries after the

original model was

discarded and forgotten by the hardy vikings. Whether the

ground on which this

theory is founded is tenable or not, it is certain that for

practical work in

rough seas on a savage and treacherous coast there is no

more serviceable craft

than the Block Island double-ender, and none other so simply

and cheaply

constructed. The visitor to Block

Island is pretty sure to linger longest at the Centre, a

hamlet lying somewhat

over a mile west of the harbor, and made up of a town-hall,

a church, half a

dozen stores, and a number of houses, set behind stone walls

and amid green

fields. One has only to pass a week of summer days here and

nearly the whole

life of the island will pass in review before him, for all

the trade of the

west and south sides centres at this point. Sunburned

farmers drive up in

vehicles of antique pattern laden with corn and barley, or

patient sheep, or

carcasses of beeves and hogs, or bundles of geese, ducks,

and turkeys, for

which the island is noted. Next comes a florid dame,

chirruping to her

slow-moving steed, her stout person flanked by pots of

butter and baskets of

eggs, and a pile of cheeses weighing down the springs behind

her. She has come

to trade, and one need have no fear that she will not hold

her own in the wordy

warfare with the merchant. A fisherman from the west side

follows, his wagon

loaded deep with bales of white, flaky codfish. Anon comes a

shore lass,

bright-eyed and agile, bearing a bundle of dried sea-moss; a

lad with an egg in

each hand, another with a pullet under each arm, a woman

with a bundle of paper

rags, a wagon filled with old junk, succeed; and so the

endless procession

continues, with few moments in the day when the merchant's

varied wares are not

being drawn upon by some needy customer. At night the store

becomes an animated

club-room, where local wiseacres gather to retail village

gossip, talk

politics, and tell stirring tales of adventure and

hair-breadth escapes on sea

and land. However, it is on the west

side, rarely visited by the summer tourist, that nearly all

that is wild,

primitive, and picturesque about the island is found. From

the Centre a walk or

ride of four miles will bring you there. The road winds and

twists through the

hollows and over the hills, with fleeting views of the sea,

its white-caps

flying, sails flitting hither and yon, and mayhap gray

phantoms of fogs

stalking up and down. The sea-breeze blows shrewdly and

covers every exposed

part with rime. Stone walls abut closely on the roads; ponds

fill the hollows,

broad meadows succeed, and then a lane branches off and

leads up to a quaint

old farm-house nestled in the midst of a little community of

haystacks,

cattle-pens, and outbuildings. The prosaic structure takes

on new interest when

you reflect that there, possibly, pretty Catherine Ray made

the famous cheese

which was presented to Benjamin Franklin, of which the great

philosopher makes

frequent mention in his letters and of which Mrs. Franklin

was so proud, or

that there General Nathaniel Greene wooed and won Catherine

Littlefield, the

modest Block Island maiden, who, later, followed him to the

camp and became

intimate with Madam Washington and other stately dames. All these things happened

somewhere on the island, and with mind filled with thoughts

of them, one leaves

behind him other pastures and meadows and farm-houses, and

at the end of an

hour's walk descends, through a rift in the bluffs, to the

west side, — a

strange, weird, mysterious coast, at which wind and sea are

ever gnawing, and

pounded by a surge whose thunder is like that from a hundred

heavy guns. In

winter, which comes early to this bleak shore, nights of

storm and darkness are

frequent, and on one of these some gallant vessel is sure to

enter the Sound at

the gateway of Montauk. The fog lowers, the gale shrieks,

and strong currents

whirl her irresistibly towards the island. Suddenly the

breakers foam beneath

her bows, there follows a sickening crash, and vessel and

crew are swallowed in

the boiling surges. Relics of a thousand such wrecks are

scattered along this

coast. The sea plays with them like a dog with the bones it

has picked, now

burying them deep in the sand, now leaving them bare and

ghastly in the

sunlight, and you meet them everywhere along the beach,

thrown up under the

cliffs or gathered in heaps, to be used as fuel for some

wrecker's winter fire. America has no coast that

has been more prolific of wrecks than this bit of land set

in the path of all

the sails that crowd the Sound. Its currents draw many to

its embrace that

would otherwise have escaped, and a volume might be filled

with records of

these wrecks. The old men delight to tell of them snugly

seated by their fires

of peat, while the blast shrieks fiercely without. Saddest

of all, they say,

attended with greatest loss of life, was the wreck of the

“Warrior,” a large

two-masted schooner, plying between New York and Boston. The

night before her

loss she was becalmed a little to the westward of Sandy

Point. During the night

a gale arose, and in the early morning she was driven with

terrific violence on

the Point. By the dim light she was seen hard aground in the

very vortex of the

conflicting currents that make this spot a seething caldron

even in moderate

weather. Waves mast-head high were pouring upon her decks,

and, although she

was but seven-score yards from shore, the islanders saw that

no mortal power

could aid the people on her decks. The end came quickly: her

masts, unstepped

at the first shock, soon fell, ripping open her main-deck;

then a wave broke

over her, and in a moment tore her into fragments, while

passengers and crew

dropped into the boiling surges. Of the twenty-one souls on

board not one was

saved. Many other notable wrecks

the old sea-dogs love to recount, and mingled with their

tales of disaster and

death are weird legends of wraiths and phantoms and spectral

crews and ships,

for nowhere else in America has superstition so long and so

tenaciously

retained its hold as it has upon the people of Block Island.

In their fancy and

belief Kidd and his crew still pay random visits to Sandy

Point, where they

bury treasures, coming under the full moon in a spectral

boat, driven by broken

surf billows. There is also the story of the little child

whose mother left it

to die by the roadside, and whose doleful cry, it is said,

is still to be heard

in the gray afternoons when the wind whistles across Clay

Head; and there is

another that has been celebrated in song and verse and is

known the wide world

over, — that of the good ship “Palatine,” alleged to have

been lured on the

rocky coast by false beacons in the last century and

afterwards pillaged by the

islanders, and whose ghostly figure, wreathed in flame, is

still seen gliding

down the Sound of nights, awaking the awe of the

superstitious and portending

some disaster to the descendants of those who were suspected

of wrecking and

robbing her. The phantom ship was last seen in February,

1880. Four days later

a party of young Block Islanders were drowned in Newport

harbor. That, on some

late and stormy winter afternoon, when the twilight is

swiftly glooming into

night, the “Palatine” will come again to Block Island is

never doubted by those

who dwell in that lonesome, wave-swept place. |