|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

VI

THE WATER FRONT

We traced the old Town front of the “convenient harbor” as best we could, through a ramble along the present marginal thoroughfares of Commercial Street and Atlantic Avenue, between Copp’s Hill at the north and the site of Fort Hill at the south. Between these bounds, and within “two strong arms” reaching out at either end of the Great Cove, the inner harbor lay through Colony and Province days. The strong arms were the North Battery on “Merry’s Point” at the foot of Copp’s Hill, and the Boston Sconce, or South Battery, on a point jutting out from Fort Hill. The North Battery commanded the mouth of Charles River; the Sconce protected the sea entrance. An additional defense at the sea end was a fort on the summit of Fort Hill, while the “Castle”, on Castle Island, where now Fort Independence Park is connected with the Marine Park system on South Boston Point, was the outer protector. Of these defenses the fort on Fort Hill was first erected, begun in the Town’s second year; the Castle next, in 1634; then the North Battery, in 1646; and lastly the Sconce, in 1666. Seven years later, in 1673, these batteries were connected by a “Barricado”, a sea wall and wharf of timber and stones, built in a straight line upon the flats before the Town across the mouth of the Great Cove, with openings at intervals to allow vessels to pass inside to the town docks. Its purpose was primarily to secure the Town from fire ships, in case of the approach of an enemy; but it was also intended for wharfage, and it came early to be called the “Out Wharves.” As a defense, the Barricado proved needless, for no hostile ship ever passed the Castle till the Revolution; it began to fall into decay early in the Province period, although it was retained for some years longer. The batteries, however, were steadily kept up and supplied with sufficient forces of men, till the Revolution was over. These were the defenses of Colony days. In the Province period, a battery was planted at the tip end of Long Wharf, the great pier stretching into the harbor nearly half a mile, built in 1710, and the wonder of its day. Bennett, in 1740, found this battery here. The North Battery is now marked by Battery Wharf on Commercial Street at the foot of Battery Street; the Sconce, by Rowe’s Wharf, at the foot of Broad Street; the Barricado, by Atlantic Avenue, which follows generally its line; while Fort Hill is represented by Independence Square—or Fort Hill Square, as the official title is—and reached from Rowe’s Wharf and Atlantic Avenue through narrow old Belcher Lane, dating back to the sixteen sixties, the “Sconce Lane” of early Province days.

The harbor front of Old Boston, therefore, extended from hill to hill, a distance of less than a mile, as the Englishman was shown by the Boston: A Guide Book map when given the foregoing details. Meanwhile the Artist had produced a copy of the familiar picture by Paul Revere— “A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New England and British Ships of War Landing their Troops, 1768”—which represents the water front of the Province period in more definite detail and in livelier manner than any other sketch or map of its time. Of the front’s appearance in Colony days there is no picture.

We enter the present front between the old bounds from the North End Terrace opposite the Charter-street side of Copp’s Hill Burying-ground, and so toward the North End Beach. Thus from the terrace we have a view across the river to the Navy Yard; while beside the beach, artificially restored a few years ago, we are close by the supposed landing place of Winthrop’s company moving over from Charlestown, and especially of Anne Pollard, then a “romping girl”, who, according to legend, was the first of all, or rather the first “female”, to spring ashore. This presumed first landing place was below Hudson’s Point, then near the junction of Charter and Commercial streets, east of Charles River Bridge, and the extreme northwest point of the Town. It got its name from Francis Hudson, a worthy fisherman, one of the early ferrymen of the Charlestown ferry, which plied from this point. Turning southeastward, along Commercial Street, we soon come upon the ancient Winnisimmet-Chelsea Ferry, at the foot of Hanover Street, one of the forgotten memorials of two centuries back. In spite of attempts to abolish it, this institution still lives and ferries in a mild way.

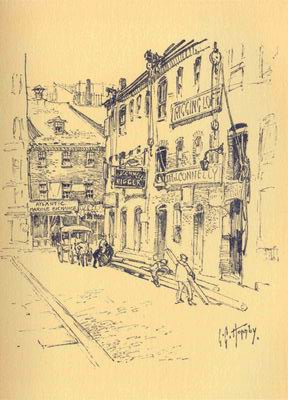

Old Loft Buildings, Commercial Wharf

Next beyond the ferry entrance we are at old Constitution Wharf, and read the inscription on a stout brass plate attached to the face of the heavy brick warehouse on the sidewalk line: “Here was built the Frigate Constitution. Old Ironsides.” That was in 1794—1797. Here was then the great shipyard of Edmund Hartt, one of three brothers — all Boston shipwrights. The capabilities of Boston at that time for the construction and equipment of ships as exemplified in the building of this famous battle frigate are remarked by the local historians. The copper, bolts, and spikes, drawn from malleable copper by a process then new, were furnished from Paul Revere’s works. The sails were of Boston manufactured sail cloth, and were made in the old Granary building. The cordage came from Boston ropewalks, of which there were then fourteen in the Town. The gun-carriages were made in a Boston shop. Only the anchors and the timber were “imported.” The anchors were from the town of Hanover, Plymouth County; the oak from Massachusetts and New Hampshire woods. Subsequently, Hartt built other ships for the young American navy before government dockyards were established, and his place came to be called “Hartt’s Naval Yard.” Notable among these productions was the frigate Boston, launched in 1799, so named because she was provided for by subscription of Boston merchants and was a free gift to the government. Another was the brig Argus, built in 1800, which distinguished herself in the War of 1812, but was finally captured by an English war brig of twenty-one guns against her sixteen. Warships were built in other Boston yards about Copp’s Hill before the Constitution was turned out. The first seventy-four gun ship built in the country, ordered by the Continental Congress, was laid in Benjamin Goodwin’s yard, near the North Battery. Forty years earlier the Massachusetts Frigate was built for the province, in Joshua Gee’s yard, at the foot of the hill, not far from Snowhill Street. She was designed for Sir William Pepperell’s expedition against Louisburg in 1745.

At that period Joshua Gee’s was one of several thriving shipyards in this neighborhood, turning out all sorts of vessels. In 1759 six were recorded as clustering about the base of Copp’s Hill; while two were at the other end of the water front below Fort Hill. In Colony days, yards here were almost as numerous. Two or three were producing handsome ships for foreign trade so early as the sixteen forties and fifties. Conveniently close by were famous taverns. There was the Ship Tavern, or Noah’s Ark, on the corner of North, then Ann, and Clark streets, dating back to before 1650, and lingering as a landmark till the eighteen sixties. And the Salutation Tavern, or the Two Palaverers, from the sign of two painted gentlemen in small clothes and cocked hats greeting each other, on Salutation Alley from Hanover Street to Commercial Street, of later date than the Ship.

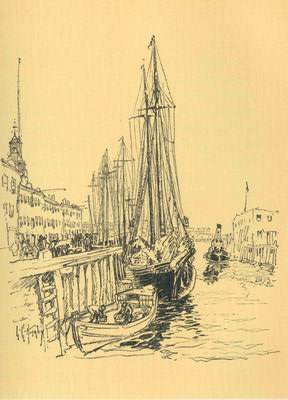

The last of the Fishing Fleet at the old T. Wharf

When the keel of the Constitution was being laid, in November, 1794, Pemberton writes, in his “Description of Boston”: “The harbor of Boston is at this date crowded with vessels. Eighty-four sail have been counted lying at two of the wharves only. It is reckoned that not less than four hundred and fifty sail of ships, brigs, schooners, and sloops and small craft are now in port.” As for shipbuilding, he tells of its having formerly been carried on at upwards of twenty-seven dockyards at one and the same time. He was credibly informed, he wrote, that in all of these yards there had been more than sixty vessels on the stocks at one time. Many, when built, were sent directly to London with naval stores, whale oil, etc., and to the West Indies with fish and lumber and rum. The whale and cod fishery employed many of the smaller craft. “They were nurseries and produced many hardy seamen,” Pemberton truly says.

We pass Battery Wharf, now a steamship pier; pass the entrance to the East Boston North Ferryways; other wharves, now steamship piers; Eastern Avenue, leading to the East Boston South Ferry; then, at Lewis Wharf, pause a moment to drop into history a bit. For here, on what is now its north side, was Hancock’s Wharf of Province days, and earlier Clark’s, the most important wharf on the water front till after the building of Long Wharf in 1710. And here was where the Great Cove started on the north side, carrying high-water mark originally up our State Street to the line of Merchants Row and Kilby Street, as we remarked on our initial ramble.

The wharf was first Thomas Hancock’s, then John Hancock’s by inheritance. John Hancock’s warehouse was upon it, while his store was at the head of what is now South Market Street; or, as described in an advertisement in the Boston Evening Post of December, 1764, “Store No. 4 at the East End of Faneuil Hall Market.” Here he was offering for sale “A general Assortment of English and India Goods, also choice Newcastle Coals and Irish Butter, cheap for Cash.” It was at this wharf that one of the British regiments landed in July, 1768, as in Paul Revere’s picture. In the previous June occurred the performance of the unloading in the night of a cargo of wines from the sloop Liberty from Madeira, belonging to John Hancock, without paying the customs, while the “tidewaiter” upon going aboard the ship, was seized by a ship captain and others following him, and confined below. Riotous proceedings followed the next day, upon the seizure of the sloop and upon its mooring for safety under the guns of a British warship in the harbor. The incensed populace turned upon the revenue officers, smashed the windows of the house of the comptroller on Hanover Street near by; and finally dragged the collector’s boat to the Common and there burnt it in a bonfire. Hancock was prosecuted upon this and many other libels for penalties upon acts of Parliament, amounting, it is said, to ninety or a hundred thousand pounds sterling. On Commercial Wharf we note the side range of low-studded, heavy granite buildings, typical of the early nineteenth-century merchants’ counting-houses that customarily lined the principal wharves. Here we enter the water-front market region.

At T Wharf, now the old fish pier, we are at what was originally a part of the Barricado of 1672. The neck of the T connecting it with Long Wharf we are told is of that structure. T is the oldest of the present wharves. Andrew Faneuil and Stephen Minott are of record as owners in 1718; but Minott was an earlier owner, and the wharf was for some time called “Minott’s T.” With the fleet of fisher boats moored at its side, it is the most picturesque and animated of all the wharves in the line. Its glory is passing now, however, with the shift of fishing interests to the new docks of the great Commonwealth Pier on the South Boston side. Long Wharf is the aristocrat of the line. It was projected in 1707, when the flats of the Great Cove had been filled on King Street below Merchants Row to about where now is the Custom House,—a pier to extend from the then foot of the street to low-water mark, some seventeen hundred feet out; and the scheme was carried through by a group of merchants as a private enterprise. Daniel Neal thus described it in 1719, nine years after its completion: a “noble Pier, eighteen hundred or two thousand Foot long, with a Row of Ware-houses on the North side for the use of Merchants”, running “so far into the Bay that Ships of the greatest Burthen may unlade without the help of Boats or Lighters.” This description practically held good till after the Revolution and into the nineteenth century. It was not till the eighteen fifties that the pier was largely widened and the range of heavy granite buildings below the Custom House, known as State Street Block, was erected in the place where ships formerly lay. At first called Boston Pier, its name in time became Long Wharf because it was “supposed to be the longest wharf on the continent.” Through Province days it was the place of landing and official reception of all distinguished arrivals. The royal governors, from Shute to Gage, at their coming landed here and were formally received, and escorted by the local military companies up King Street to the Town House. Here the main body of the troops embarked for the Bunker Hill Battle on Breed’s Hill; and hence departed the army and the royalists at the Evacuation. The first house set up at the head of the pier was a tavern—the Crown Coffee House. Neighboring water resorts early followed, to become historic inns. There was first the Bunch of Grapes on the west corner of Kilby Street, begun before 1712; later, the British Coffee House, nearly opposite; and the Admiral Vernon, named in honor of Edward Vernon, the English admiral, on the lower corner of Merchants Row. The Bunch of Grapes was the tavern which the jovial young merchant of New York, Captain Francis Goelet, here in 1750, described in his journal recording his entertainment by the bucks of the town, as the “best punch house in Boston”, which vinous sobriquet it retained through its long career. In pre-Revolutionary days it was the chosen resort of the patriot leaders, while the British Coffee House was the rendezvous of the British officers. Near the head of the pier were the warehouses of the Faneuils—Andrew, Peter, and Benjamin. When the Custom House was built, in 1837—1847—the low, granite-pillared, Greek-like structure from whose modest dome springs the towering pyramid that now dominates the sky line—it stood at the head of the wharf with the bowsprits of vessels lying there stretching across the Street almost touching its eastern part. It is an interesting tradition, by the way, that on the site of the Custom House lived a cooper who turned out to have been a leader of the Fifth Monarchy Men.

Central and India wharves, now piers of Maine and of New York steamboat lines, are among the oldest, as they are the finest, of the present wharves of this front. Central, with its range of more than fifty stores, dates from 1816; India, with a row of sixty odd, from 1806. Central Wharf was laid out originally over a part of the Barricado structure then still remaining. Near its head, on Custom House Street, the Old Custom House, predecessor of the present one, erected in 1810, yet stands, stripped, however, of the architectural adornments of its façade, and of the spread eagle which once topped the pediment. The old building has a pleasant literary interest as the Custom House of George Bancroft and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s time,—Bancroft as collector, Hawthorne in the humbler post of weigher and gauger. Of the “Tea Party Wharf” or of its successor — Griffin’s in the tea-ship’s time, later Liverpool Wharf— no vestige remains, our guest was told. With curious interest he read the elaborate inscription reciting the story, beneath the model of a tea-ship, on the tablet attached to a building on the north corner of the avenue and Pearl Street. This tablet marks the wharf’s site only in a general way.

Rowe’s Wharf, now a popular harbor steamboats’ pier, dates back to before 1764, and originally was on the northerly side of Sconce, afterward Belcher, Lane. Here we turn from the avenue, and entering Belcher Lane, finish our ramble in Fort Hill Square, the poplars of which we see at the end of the vista. As we loiter in this serene little park in the heart of a busy wholesale quarter, we note that it marks the lines of a plot on the summit of the hill that rose a hundred feet above, within which had stood the fort that gave the hill its name, and the larger fort that succeeded the first one, in which Andros found refuge in April, 1689, when the townspeople rose against and overthrew him. Till after the Revolution the summit was open ground, and in Province days a public mall. Here the anti-Stamp Act mob of 1765 had their bonfire of the wreckage of the Stamp office on Kilby Street, and of the fence of the stamp master’s, Andrew Oliver, place on the hillside, in sight of his mansion. Here an ox was roasted for the people’s feast at the celebration of the news of the French Revolution. The slopes of the hill became favorite dwelling places in early Colony days, and in Province days some fine seats occupied the hillside. In the latter eighteenth and the early nineteenth century the approach was marked by terraced gardens reaching to the hill top. In the eighteen thirties the plot on the summit was laid out as Washington Square, a circular green adorned with noble trees and surrounded by a Street of genteel dwellings. In course of time its prosperity waned, and the genteel dwellings became squalid tenements. Then Fort Hill fell into ignoble decay. It remained, however, till the last of the eighteen sixties. Its leveling was begun in 1869, but the process was slow, and the ancient landmark did not wholly disappear till after the “Great Boston Fire” of 1872.