CHAPTER

XIII

THE

VALE OF TEIFY

WELSHMEN call the county

of Cardigan the Shire Aber Teivi, or the shire of the River Teify.

The valley of this river forms the boundary between the shire and

those of Pembroke and Carmarthen, and then turns north-east to the

famous monastery of Strata Florida, which is well worth a visit to

those who love to remember that Wales was the home of the Christian

faith in days when England lay in heathen darkness.

We saw in the last

chapter that Cardigan is a lonely county, cut off from its neighbours

by mountains and hills all the way from Plynlimmon to Lampeter,

and by steep slopes, forming the Valley of the Teify, on the

Carmarthen side. Hence its position has made it in bygone days "the

last refuge of the beaten and the first landing-place of returning

exiles."

Its people, because of

this fact, are not quite like the rest of their countrymen, but form

something like a separate tribe, known to their neighbours as

"Cardys." The men are generally very dark as to eyes, hair,

and complexion, with "round heads, thick necks, and sturdy

frames."

You remember that Borrow

took his guide for an Irishman at first, and in many ways the "Cardy"

does resemble his Celtic cousin across the Channel of St. George. But

he differs in the fact that he is very industrious and independent,

and always on the lookout to better himself. So that, though nearly

all the population is composed of small farmers and their labourers,

the county is said to produce more teachers, parsons, and preachers

than any other in Wales.

We have heard something

already of the tremendous battles that took place in this

region—battles which we can easily account for, since the

loneliness of the district made it a favourite refuge for all lost

causes. The story of one of these battles, the joy of the Welsh bards

in the twelfth century, tell us how North and South Wales joined in

1135 in an attack upon the town of Cardigan, at the mouth of the

Teify, then held by ruthless English barons, who advanced beyond the

walls upon them. The advantage falling to the Welsh, the English

retreated to their castle, but the Welshmen cut the supports of the

bridge over the Teify as they crossed it, so that three thousand

perished in the river.

"The green sea-brine

of Teife thickened. The blood of warriors and the waves of ocean

swelled its tide. The red-stained sea-mew screamed with joy as it

floated on a sea of gore." 1

From Cardigan the River

Teify winds through a hilly country to Cenarth, whose castle is the

scene of a story all too common in the days when Henry I. was King of

England.

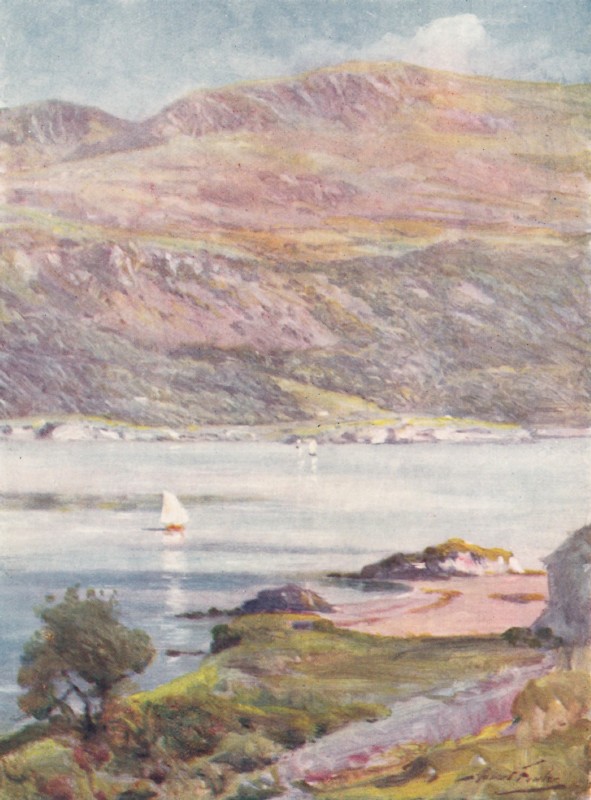

CARDIGAN BAY

Nest, the daughter of

Rhys ap Tudor, the last Prince of Wales who was actually quite

independent of English rule, was the fairest maiden in all the land.

When her father died, he

left her in the charge of Henry I., and the King gave her in marriage

to the Norman Gerald, Lord of Pembroke, who had just built this

castle at Cenarth as a protection against the hostile Welsh on both

sides of the river. There he lived happily with his beautiful wife

and children for some years, until Cadogan, Prince of Cardigan, took

it into his head to give a great banquet at Cardigan Castle.

Now, at this feast the

one topic of conversation and song was the beauty of Nest, the wife

of the Norman baron, and at length the wild son of Cadogan, Owen by

name, arose and declared that he would carry her off and bring her

back to her own people.

So one dark night, Owen

and his band of followers forced their way into Pembroke Castle,

where the Earl and his wife were then living, and into the room where

Gerald and Nest lay asleep.

The baron barely saved

his life by escaping down a drain, while his wife and children were

carried off and the castle fired. The unhappy Nest was hidden, they

say, in a romantic old house near Llangollen, and meantime all Wales

was in an uproar about the ears of the daring robber.

The wrath of Henry of

England fell hot upon Cadogan, who had tried in vain to persuade his

son to restore his prisoner. Most of his land was taken from him by

jealous neighbours as well as by the English barons of the border,

and at length the turbulent Owen was forced to flee to Ireland, and

Nest returned to her husband.

Many years later, says

the tale, Owen returned, an outlaw, to his native land, and before

very long found himself fighting in a quarrel on the same side as the

injured Gerald. No sooner did the latter discover this than, mindful

of the ancient feud, he sought out his rival and challenged him to

single conflict, putting him at last to death. And still they show

below that old manor-house at Eglyseg, the hiding-place and prison of

poor Nest, the path that climbs the steep glen, and claim it to have

been the way by which Owen set out upon his wild quest and returned

with his terrified captives.

But we must hasten along

the deep and rocky valley of our river, past the little town of

Lampeter, noted for its training college for those who are going to

be clergymen, and through a fair country of meadows and hills till we

turn aside to a very ancient village, with a still more ancient

church. This is Llan-Dewi-Brefi, or the Church of St. David on the

Brefi. We have heard of it in a former chapter, for it was the scene

of St. David's triumph over the heretics in the sixth century, and

the church stands on the site of that which was built in memory of

that triumph on the hill which rose under him as he stood to give his

message to the assembly.

The word "Brefi"

means a "bellowing," and legend accounts for the name of

the little stream which flows by the hill in this fashion.

Two mighty oxen were

dragging stones from the river-bed wherewith to build the church,

when they came to a very steep hill, up which they found it most

difficult to pull the huge stone. At last, in his struggle to do so,

one of the animals fell down dead. When this happened, its mate stood

and bellowed nine times with force so terrific that the valley shook,

and the hill fell down flat, so that the stone could be drawn easily

to the site of the church. Once on a time the traveller would be

shown an immense horn, said to have fallen from the head of one of

these oxen, which gave its name of the "Bellowing One" to

the stream below.

To the left of the Teify

Valley, some miles farther up its course, lies the great Bog of

Tregaron, six miles long and one broad, and far more like an Irish

bog than any other quagmire in this country.

Picture to yourself a

vast flat, brownish expanse, with pools of gleaming black water here

and there, dotted by hillocks formed by stacks of black turf cut from

its surface. It is loneliness itself, in spite of a brown-smocked

turf-cutter here and there at work; and over it the only sound that

echoes is the cry of the wild-duck, the peewit, or grouse.

Farther up still we find

the Teify among the mountains, flowing in a valley, at the head

of which stand the ruins of Strata Florida. Most solitary is this,

perhaps, of all the lonely spots which those old Cistercian monks

chose out in the wilderness, and "made to blossom like the

rose."

The monastery was

probably founded by Rhys ap Griffith in 1164—"My Lord Rhys,

the head, and shield, and strength of the south and of all Wales,"

as the chronicler calls him. It became the darling of the Welsh

chieftains, who showered lands and money upon the monks, until they

found themselves the owners of the mountain-range above, and of most

of the wide valley in which stand the ruins, and the most noted

sheep-farmers in Wales.

In one of these cells was

preserved the parchment, still in existence, upon which was kept,

every day for one hundred and thirty years, a "chronicle"

of the Welsh history of the time, which only ends with the death of

Llewelyn.

Here, too, lies buried

beneath the great yew-trees of the graveyard a famous Welsh poet of

the fourteenth century, named Dafydd ap Gwilym (David, son of

William).

Welsh literature is full

of the love-poems addressed by this poet to Morfydd, his loved one, "

Maid of the glowing form and lily brow beneath a roof of golden

tresses."

She was above him in

birth, and was sent to a convent in Anglesey to be out of his way. Ap

Gwilym, disguised as a monk, followed her to a monastery close by,

but only to hear that she had been married to a husband much older

than herself. In desperation the bard tried to carry her off, but was

seized and thrown into a Glamorgan prison until he could pay a large

fine. But his fellow-poets would not let the "chief bard of

Glamorgan" languish in a dungeon; they paid his fine, and set

the prisoner free to sing again of Nature and of love.

Ap Gwilym died in the

year of Glendower's revolt, still grieving for his lost Morfydd, and,

with her name on his lips, passed away, and was buried under the

walls of the great abbey that had sheltered his last years.

1

The quotation is taken from Bradley's "Highways and Byways of

South Wales."

|