NEWS

OF SPRING

I HAVE

seen the manner in

which Spring stores up sunshine, leaves and flowers and makes ready,

long beforehand, to invade the North. Here, on the ever balmy shores

of the Mediterranean — that motionless sea which looks as though it

were under glass — where, while the months are dark in the rest of

Europe, Spring has taken shelter from the wind and the snows in a

palace of peace and light and love, it is interesting to detect its

preparations for travelling in the fields of undying green. I can see

clearly that it is afraid, that it hesitates once more to face the

great frost-traps which February and March lay for it annually beyond

the mountains. It waits, it dallies, it tries its strength before

resuming the harsh and cruel way which the hypocrite winter seems to

yield to it. It stops, sets out again, revisits a thousand times,

like a child running round the garden of its holidays, the fragrant

valleys, the tender hills which the frost has never brushed with its

wings. It has nothing to do here, nothing to revive, since nothing

has perished and nothing suffered, since all the flowers of every

season bathe here in the blue air of an eternal summer. But it seeks

pretexts, it lingers, it loiters, it goes to and fro like an

unoccupied gardener. It pushes aside the branches, fondles with its

breath the olive-tree that quivers with a silver smile, polishes the

glossy grass, rouses the corollas that were not asleep, recalls the

birds that had never fled, encourages the bees that were workers

without ceasing; and then, seeing, like God, that all is well in the

spotless Eden, it rests for a moment on the ledge of a terrace which

the orange-tree crowns with regular flowers and with fruits of light,

and, before leaving, casts a last look over its labour of joy and

entrusts it to the sun.

II

I HAVE

followed it, these

past few days, on the banks of the Borigo, from the torrent of Careï

to the Val de Gorbio; in those little rustic towns, Ventimiglia,

Tende, Sospello; in those curious villages, perched upon rocks, Sant’

Agnese, Castellar, Castillon; in that adorable and already quite

Italian country which surrounds Mentone. You go through a few streets

quickened with the cosmopolitan and somewhat hateful life of the

Riviera, you leave behind you the band-stand, with its everlasting

town music, around which gather the consumptive rank and fashion of

Mentone, and behold, at two steps from the crowd that dreads it as it

would a scourge from Heaven, you find the admirable silence of the

trees, all the goodly Virgilian realities of sunk roads, clear

springs, shady pools that sleep on the mountain-sides, where they

seem to await a goddess’s reflection. You climb a path between two

stone walls brightened by violets and crowned with the strange brown

cowls of the arisarum, with its leaves of so deep a green that one

might believe them to be created to symbolize the coolness of the

well, and the amphitheatre of a valley opens like a moist and

splendid flower. Through the blue veil of the giant olive-trees that

cover the horizon with a transparent curtain of scintillating pearls,

gleams the discreet and harmonious brilliancy of all that men imagine

in their dreams and paint upon scenes that are thought unreal and

unrealizable, when they wish to define the ideal gladness of an

immortal hour, of some enchanted island, of a lost paradise, or the

dwelling of the gods.

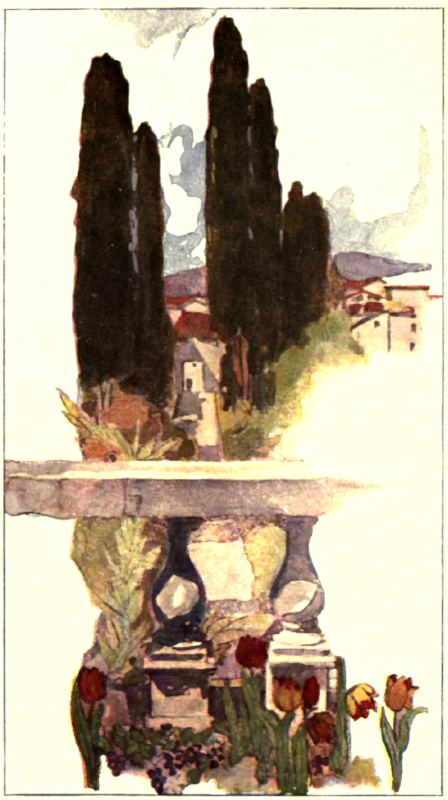

III

ALL

along the valleys of

the coast are hundreds of these amphitheatres which are as stages

whereon, by moonlight or amid the peace of the mornings and

afternoons, are acted the dumb fairy-plays of the world’s

contentment. They are all alike, and yet each of them reveals a

different happiness. Each of them, as though they were the faces of a

bevy of equally happy and equally beautiful sisters, wears its

distinguishing smile. A cluster of cypresses, with its pure outline;

a mimosa that resembles a bubbling spring of sulphur; a grove of

orange-trees with dark and heavy tops symmetrically charged with

golden fruits that suddenly proclaim the royal affluence of the soil

that feeds them; a slope covered with lemon-trees, where the night

seems to have heaped up on a mountain-side, to await a new twilight,

the stars gathered by the dawn; a leafy portico which opens over the

sea like a deep glance that suddenly discloses an infinite thought; a

brook hidden like a tear of joy; a trellis awaiting the purple of the

grapes, a great stone basin drinking in the water that trickles from

the tip of a green reed — all and yet none modify the expression of

the restfulness, the tranquillity, the azure silence, the

blissfulness that is its own delight.

IV

BUT I am

looking for

winter and the print of its footsteps. Where is it hiding? It should

be here; and how dares this feast of roses and anemones, of soft air

and dew, of bees and birds, display itself with such assurance during

the most pitiless month of Winter’s reign? And what will Spring do,

what will Spring say, since all seems done, since all seems said? Is

it superfluous, then, and does nothing await it? No; search

carefully: you shall find amid this life of unwearying youth the work

of its hand, the perfume of its breath which is younger than life.

Thus, there are foreign trees yonder, taciturn guests, like poor

relations in ragged clothes. They come from very far, from the land

of fog and frost and wind. They are aliens, sullen and distrustful.

They have not yet learned the limpid speed, not adopted the

delightful customs of the azure. They refused to believe in the

promises of the sky and suspected the caresses of the sun which, from

early dawn, covers them with a mantle of silkier and warmer rays than

that with which July loaded their shoulders in the precarious summers

of their native land. It made no difference: at the given hour, when

snow was falling a thousand miles away, their trunks shivered, and,

despite the bold averment of the grass and a hundred thousand

flowers, despite the impertinence of the roses that climb up to them

to bear witness to life, they stripped themselves for their winter

sleep. Sombre and grim and bare as the dead, they await the Spring

that bursts forth around them; and, by a strange and excessive

reaction, they wait for it longer than under the harsh, gloomy sky of

Paris, for it is said that in Paris the buds are already beginning to

shoot. One catches glimpses of them here and there amid the holiday

throng whose motionless dances enchant the hills. They are not many

and they conceal themselves: they are gnarled oaks, beeches, planes;

and even the vine, which one would have thought better-mannered, more

docile and well-informed, remains incredulous. There they stand,

black and gaunt, like sick people on an Easter Sunday in the

church-porch made transparent by the splendour of the sun. They have

been there for years, and some of them, perhaps, for two or three

centuries; but they have the terror of winter in their marrow. They

will never lose the habit of death. They have too much experience,

they are too old to forget and too old to learn. Their hardened

reason refuses to admit the light when it does not come at the

accustomed time. They are rugged old men, too wise to enjoy

unforeseen pleasures. They are wrong. For here, around the old,

around the grudging ancestors, is a whole world of plants that know

nothing of the future, but give themselves to it. They live but for a

season; they have no past and no traditions and they know nothing,

except that the hour is fair and that they must enjoy it. While their

elders, their masters and their gods, sulk and waste their time, they

burst into flower; they love and they beget. They are the humble

flowers of dear solitude, — the Easter daisy that covers the sward

with its frank and methodical neatness; the borage bluer than the

bluest sky; the anemone, scarlet or dyed in aniline; the virgin

primrose; the arborescent mallow; the bell-flower, shaking its bells

that no one hears; the rosemary that looks like a little country

maid; and the heavy thyme that thrusts its grey head between the

broken stones.

But,

above all, this is

the incomparable hour, the diaphanous and liquid hour of the

wood-violet. Its proverbial humility becomes usurping and almost

intolerant. It no longer cowers timidly among the leaves: it hustles

the grass, overtowers it, blots it out, forces its colours upon it,

fills it with its breath. Its unnumbered smiles cover the terraces of

olives and vines, the tracks of the ravines, the bend of the valleys

with a net of sweet and innocent gaiety; its perfume, fresh and pure

as the soul of the mountain spring, makes the air more translucent,

the silence more limpid and is, in very deed, as a forgotten legend

tells us, the breath of Earth, all bathed in dew, when, a virgin yet,

she wakes in the sun and yields herself wholly in the first kiss of

early dawn.

V

AGAIN,

in the little

gardens that surround the cottages, the bright little houses with

their Italian roofs, the good vegetables, unprejudiced and

unpretentious, have known no fear. While the old peasant, who has

come to resemble the trees he cultivates, digs the earth around the

olives, the spinach assumes a lofty bearing, hastens to grow green

nor takes the smallest precaution; the garden bean opens its eyes of

jet in its pale leaves and sees the night fall unmoved; the fickle

peas shoot and lengthen out, covered with motionless and tenacious

butterflies, as though June had entered the farm-gate; the carrot

blushes as it faces the light; the ingenuous strawberry-plants inhale

the flavours which noontide lavishes upon them as it bends towards

earth its sapphire urns; the lettuce exerts itself to achieve a heart

of gold wherein to lock the dews of morning and night.

The

fruit-trees alone

have long reflected: the example of the vegetables among which they

live urged them to join in the general rejoicing, but the rigid

attitude of their elders from the North, of the grandparents born in

the great dark forests, preached prudence to them. But now they

awaken: they too can resist no longer and at last make up their minds

to join the dance of perfumes and of love. The peach-trees are now no

more than a rosy miracle, like the softness of a child’s skin

turned into azure vapour by the breath of dawn. The pear and plum and

apple and almond-trees make dazzling efforts in drunken rivalry; and

the pale hazel-trees, like Venetian chandeliers, resplendent with a

cascade of gems, stand here and there to light the feast. As for the

luxurious flowers that seem to possess no other object than

themselves, they have long abandoned the endeavour to solve the

mystery of this boundless summer. They no longer score the seasons,

no longer count the days, and, knowing not what to do in the glowing

disarray of hours that have no shadow, dreading lest they should be

deceived and lose a single second that might be fair, they have

resolved to bloom without respite from January to December. Nature

approves them, and, to reward their trust in happiness, their

generous beauty and amorous excesses, grants them a force, a

brilliancy and perfumes which she never gives to those which hang

back and show a fear of life.

All

this, among other

truths, was proclaimed by the little house that I saw to-day on the

side of a hill all deluged in roses, carnations, wall-flowers,

heliotrope and mignonette, so as to suggest the source, choked and

overflowing with flowers, whence Spring was preparing to pour down

upon us; while, upon the stone threshold of the closed door,

pumpkins, lemons, oranges, limes and Turkey figs slumbered in the

majestic, deserted, monotonous silence of a perfect day.

|