II.

CHIEF GODS AND MYTHS OF THE GODS

(THOR)

1. Worship

of Odin and Thor. Attention has

already been

called in the general introduction to the fact that Thor was the

Norseman's real chief divinity from a very ancient time, and that his

name "the Thunderer" designates only a single side of the

God of Heaven; but he was later understood to be an independent,

personal being. Odin worship is far younger and made its way north

from a Germanic people dwelling farther south. In the consciousness

of the common people, conceptions of Thor as the supreme god were

never superseded; but Odin faith received full and pleasing

development in Norse-Icelandic poetry.

Thor

as Chief God. Thor was at one time the chief divinity with

all the Gothic-Germanic peoples. Not only does the general occurrence

of the symbol of the hammer bear witness to this, but also the fact

that he is placed by the side of Jupiter, since Jupiter's day is

rendered by Thor's day. An old Low-German baptismal formula begins as

follows:

"Do

you renounce the devil

and

all offerings to the devil

and

all the works of the devil?"

"I

renounce all the devil's works and words,

Thunar

and Woden and Saxnot and all

the

Trolls

which are worshiped here."

Thor,

Odin, and "Saxnot" (the one armed with the sword) are

precisely the three chief gods who are most often named in Norse

sources, provided we can identify Saxnot with Frey. It is at the same

time not solely the significance of the name and the hammer-symbol,

or the testimony of rune stones, which tell us about the extent of

the worship of Thor. The same testimony recurs in names of persons

and places, in which we find Thor in overwhelming abundance, compared

with Odin and Frey. Where heathen temples are mentioned, statues of

the chief gods in them are sometimes named, and in that case Thor's

name ordinarily comes first, as in the baptismal formula above. Most

often a temple of Thor only is mentioned, or a representation of Thor

alone. The Yule-offering, the chief offering of our heathen

forefathers, was consecrated to Thor, and Thor's day appears as the

most important week-day in all legal questions; the court was opened

on a Thursday, and Thursday is the most common court day even now.

Norwegian-Icelandic poetry itself gives here and there unmistakable

evidence of Thor's prominent position.

2. Mithgarth's

Keeper. The Volva's Prophecy in

its

description of Ragnarok in the verse cited calls Thor, as Mithgarth's

Keeper,1 "Veurr." Veurr,

related to the

Danish word vie, 'to consecrate,' and to Ve, 'sanctuary,' signifies

protector and consecrator, and Mithgarth is certainly the land of

human beings. Other poets call him Friend of Human Kind

or Defender of the Race, and he occupies a

similar position even

among the gods, who constantly seek protection through his strength

even if Odin or Frey is present. Therefore he is called Asa-bragr,

the most prominent of Aesir. Thor is consecrator and protector of all

human life; he thereby becomes the protecting divinity not merely of

the individual man, but also of the home and the state. He is the

great god of civilization, with the strongest and mightiest powers at

his command, the lightning the hammer, i.e. the thunderbolt

which crushes and splinters whatever offers resistance (desolate

nature in giant forms) but which also brings with it fruit-producing

rain.

3. Characteristics

of Thor. People most often

picture Thor to

themselves as a strong middle-aged man, rarely a young man, but in

both cases he has a glowing red beard. lie is tremendously strong;

his flaming glance is enough to terrify any one, and he is dreadful

in his wrath, but under ordinary circumstances lie is gracious and

mild. When he, in his wagon drawn by he-goats, drives over the sky,

this is in flames and the mountains tremble or burst in the thunder's

crash. The modern Danish Torden, 'thunder,' means

'Thor-rumbling,' like the older Danish form; the Swedes say aska,

the word being a contraction of as-eka, 'driving of

As.'

To

Thor's name there are attached a number of myths or divine

traditions, and of these we shall now recount the most important.

4. The

God's Treasures. Of the origin of the

god's treasures,

Snorri relates the following: Loki had once from malice cut off the

hair of Thor's wife Sif. When Thor became aware of

it, he

wanted to crush every hone in Loki's body; but the latter promised to

get golden hair from the dark elves for Sif in compensation. He

applied therefore to the dwarfs, who are called the sons of Ivaldi,

and they upon his demand made hair for Sif, the spear Gungnir

which Odin received, and the ship Skithblathnir

which could

sail over both sea and land hut could also be folded together and

carried in a pouch, in case one preferred. This good ship Frey

received. After that Loki wagered with a dwarf Brok,

staking

his head that the latter's brother Sindri could not

complete

three equally good treasures. Brok plied the bellows and Sindri

forged, and although Loki in the form of a gadfly three times stung

the one plying the bellows and forced him to stop a moment, Sindri

notwithstanding finished the three great pieces of work: the boar Gullinbursti,

the ring Draupnir,

and the hammer Mjolnir. Loki with his stings accomplished

only this, that the

hammer handle remained a little too short. The wager was to be

settled in Asgarth. Thor took the hammer, Odin the ring, and Frey the

boar, after which these three gods were to pronounce judgment. The

hammer decided the matter, and Loki was now to lose his head. He

ordered Brok to take it, but the neck must not be touched, since the

wager applied only to the head itself. In exasperation, the dwarf

then sewed Loki's wily mouth together.

5. The

Hammer is Recovered. One of the oldest

Eddic Songs

relates how Thor lost his hammer and recovered it. Angry awoke

Ving-Thor and missed his hammer; his beard and hair shook; the son of

Jorth groped around, hut the hammer was lost and could not he found.

Loki, to whom the god of thunder describes his loss, borrows Frey's

feather garment and flies over to the king of the giants, Thrym.

The latter admits having concealed the hammer deep in the earth, and

he will not give it hack unless Freyja is brought to him as his

bride. Loki flew back and the demand of the king of the giants was

communicated to the goddess of love, but

THKRV.

12

Wroth

grew Freyja, and she fumed,

all

the Aesir's hall trembled therefrom,

there

bursts that great Brisinga chain 2;

Thou

knowst me to be most mad for men,

if

I drive with thee to Jotunheim."

The

Aesir and Asynjur, 'goddesses,' assembled for

deliberation at

the court to consider how the hammer could be regained. Heimdall

solves the problem: "Let us bind bridal linen about Thor and

give him the great Brisinga ornament to put on; keys shall rattle at

his girdle, women's garments fall about his knees, head and breast be

decked in woman's fashion." Thor must submit to the hard

necessity, for the giants will take possession of Asgarth if he does

not regain the hammer. Loki, Laufey's son, also dresses in women's

clothes, so as to follow Thor as his maid upon the strange bridal

journey.

21

Soon

were the goats driven homeward,

hurried

to the traces, they must run well;

mountains

burst, earth burned with fire,

Odin's

son drove into Jotunheim.

In

Jotunheim there is prepared a splendid bridal feast, but Thor is ill

adapted to the bride's part. At first his ability to eat and drink

awakens amazement, nay, almost terror, in Thrym; and when the

bridegroom lifts the veil to kiss his bride, he darts back

terror-stricken the length of the hall, for Freyja's eyes are sharp

and shine like fire. The artful bridesmaid meantime comforts him with

assurance that the goddess's appetite and piercing glances were due

only to her yearning for the bridegroom, since she had neither eaten

nor slept in eight days.

THRKV.

30

Then

quoth Thrym the giants' chief:

Bear

in the hammer to bless the bride!

Mjolnir

place on the maiden's knees,

bless

and join us by the hand of Varr.

Now

comes the hour of reparation and vengeance for Asgarth's mighty god:

31

Laughed

Hlorrithi's heart within his breast,

when

he, hard-hearted, the hammer perceived;

Thrym

he slew first, the giants' chief,

and

the giant's race all he crushed.

The

wretched sister of the giant had begged for a bridal gift; she

received a hammer-blow instead of golden rings. After this the

thunder-god returned to Asgarth with his recovered weapon.

The

same theme is treated in a jesting manner in the ancient Danish

ballad about Tor of Havsgaard. Tor of Haysgaard

rides over

green meadows and loses his golden hammer. Lokke Lojemand (jester)

puts on the feather cloak and seeks out the Tossegreve,

'foolish count,' who has hidden the hammer and will not give it back

unless he gets "Jomfru Fredensborg (Miss Peacecastle) with all

the goods she has." After this, Tor and Lokke, as in the Eddic

Song, must put on women's clothes and proceed to the Tossegreve's

land. Tor's appetite in the ancient ballad is quite astonishing

he ate a whole ox and thirty hams; no wonder that he was thirsty

after that! But when the hammer was brought in, it was evident that

he could use it, and the Tossegreve with all his tribe were crushed.

The ballad ends thus:

Lokke

said this, crafty man,

he

did consider it well:

Now

we will fare to our own land,

as

the bride has become a widow.

6. Hymir's

Kettle. Thor one time, relates the

Lay of Hymir,

had to go to the giant Hymir for a great kettle which was to be used

at a feast for the gods at the home of the sea-god Aegir. lie sets

out together with Tyr, and they reach the giant's dwelling. The

latter does not come home until towards night, and is much offended

both at his guests and at Thor's appetite. The following morning Thor

goes out with the giant to fish. The god demands bait of the

ferocious giant, who asks him to look out for it himself. Thor then

wrenches the head from one of the giant's black oxen, after which

they begin to row. Hymir is frightened at Thor's violent strokes and

objects to keeping on for fear of coming upon the Mithgarth serpent.

This, however, is exactly Thor's purpose, and while the giant is

attending to his affairs, Thor makes the "Earth-Encircler"

swallow the hook and draws his head up to the surface of the sea. At

the same moment when he wishes to crush his skull the terror-stricken

giant cuts the line and the monster sinks back safe upon the bottom

of the sea. This adventure has again and again inspired our

forefathers. One of the very oldest Scalds gives a graphic picture of

how the "Earth-Encircler," like a wildly floundering eel,

gazes defiantly from the depths below up at the "Cleaver of the

Giant's Skull," who is only waiting to give him the fatal blow

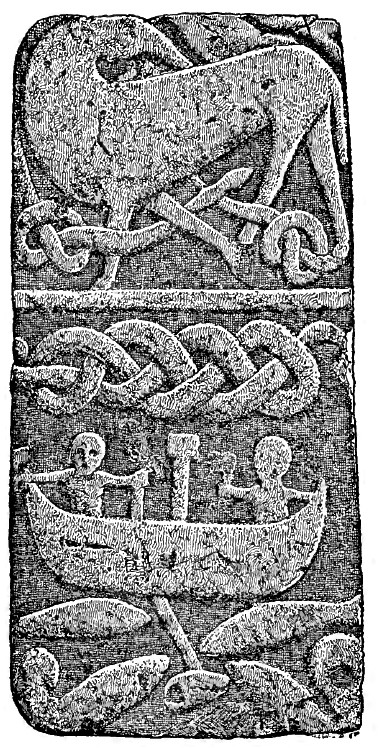

(cf. Fig. 19).

Fig.

19 Thor's Fishing.

In

Snorri, Thor in his godlike strength breaks through the planks of the

boat until he gets a footing on the bottom of the sea. As the giant

has hindered him in his purpose, Thor hurls his hammer after the

serpent and chastises the giant with a frightful box on the ear,

after which he himself wades ashore. The poem on the other hand has

them both turn back together, just as they went out. Thor, however,

may not now obtain the kettle until he can further prove his strength

by crushing the giant's beaker. That does not break until the god

hurls it against the owner's own skull, after which he snatches the

kettle and carries it from the court, pursued by the giant's hosts,

which he crushes with his hammer.

7. Hrungnir.

The myth of Thor and Hrungnir

has been

very widespread and popular, and the Scalds often alluded to it; but

in connected form it is preserved only in Snorri. Once when Thor was

in the East in order to crush the trolls, Odin seated himself upon

Sleipnir and rode to Jotunheim. Here he met the giant Hrungnir, who

boasted that his steed Gullfaxi was far better than

Odin's.

Odin rode back to Asgarth, but the giant followed him even into the

dwelling of the gods. Now drink was borne before him, but when his

boasting become too arrogant, the gods called upon Thor, who quickly

appeared and was on the point of crushing the giant. The latter

intimated that it was only a slight honor to slay a defenseless foe;

he must rather meet him in a duel at the frontier, where Hrungnir

would then appear with shield and grindstone. Such a challenge Thor

did not allow to be offered twice, and the giant went away satisfied.

As help for him the other giants built now a champion of clay, nine

rasts high, and three rasts broad between the shoulders. He was

called Mokkrkalfi, and he had a mare's heart in his

breast;

Hrungnir's heart was a three-cornered stone. At the appointed time

Thor made his appearance, attended by Thialfi. The

giant stood

with the shield before him and the grindstone in his hand. At the

same time Thialfi went forward and called to him that Thor was coming

from below, after which Hrungnir stepped upon his shield and grasped

the grindstone with both hands. Thor meanwhile went forward through

the air amidst lightning and crash of thunder. The grindstone and

hammer were hurled at the same time and met midway; Mjolnir holds its

course and crushes the giant, hut half of the stone strikes Thor in

the forehead so that he falls to the ground in such a way that the

giant's foot lies across his neck. Thialfi strove with the clay

giant, who trembled with fear and fell with little glory. Meanwhile

no one could lift the giant's leg away, until Thor's three-year-old

son Magni came up; he then received Gullfaxi as a

reward for

his strength, although Odin himself had meant to have that good

steed.

When

Thor came back to Thruthvang, the healing woman, Groa,

was

brought, who recited magic songs over him until the stone began to

sway in his forehead. Snorri adds that it did not, however, get

completely loose, for Thor told Groa that her husband, Orvandil,

was coming home presently. Thor had borne him on his back in a basket

over the poisonous streams on the return journey from Jotunheim. One

of his toes, however, was frozen off, and Thor had cast it up to

heaven and made it into a star. But Groa became so joyful at this

information that she forgot her witchcraft.

8. Geirroth.

Loki had once been caught by the

giant Geirroth,

to whose court he had from curiosity betaken himself in Frigg's

falcon cloak. In order to get free he had to promise to bring Thor to

Geirroth without his hammer or his strength-belt. In this the artful

Loki was easily successful, but on the way Thor visited the giantess

Grith, Vithar's mother. She instructed him about Geirroth and lent

him at parting her strength-belt, her iron gloves, and her staff.

Thor came first to a brook in which one of the giant's daughters had

occasioned an inundation. He slew her and escaped to land by drawing

himself up into a mountain ash. In Geirroth's hall there was only one

chair, and it went up quickly as far as the ceiling when Thor seated

himself upon it. He then pressed against it with Grith's staff and

pushed with all his might, after which there was heard a great roar,

for the giant's daughters had been under the chair and lay there now

with broken backs. On the floor there was kindled a great fire,

beside which people took their seats. Geirroth then seized a glowing

iron wedge and cast it at Thor, who caught it with the borrowed

gloves, after which the giant hid himself in terror behind a mighty

iron pillar. Thor now hurled the wedge with such force that it

pierced through the pillar and Geirroth also, and went out through

the wall on the opposite side. The main source of this myth is the

obscure Scaldic lay Thorsdrapa, which is retold by

Snorri.

9. Thor's

Journey to Utgarth. In Snorri is also

found the

late adventure of Thor's journey to Utgarth, which

probably is

the best known. This tale attained great celebrity after

Oehlenschlaeger made use of it as the basis for his poem, "Thor's

Journey to Jotunheim," 3 the introduction to

"Gods

of the North."4 Snorri's long account is a free

and

fanciful transformation of a whole series of Thor-myths now for the

most part lost.

a.

Thor gets Thialfi and Roskva from the peasant (Egil).

b.

The meeting with Skrymir (the gloves, lunch bag, Thor's

hammer-thrust.

c.

Utgarthaloki (the eating test and the race. Thor drinks from the sea,

lifts the Mithgarth serpent, and wrestles with Elli, i.e. Old Age).

d.

The optical illusion is removed and Thor wishes to take vengeance,

but without success.

10. Alvis.

An entirely characteristic but not

very transparent

myth lies also at the basis of the Eddic Song of Alvis.

Alvis

is a dwarf who, without its being evident wherefore and from whom,

has received the promise of Thor's daughter. He now comes to take

her, but is addressed with scornful words by Thor. The dwarf does not

know him and asks him to mind his own business; only when he is

informed who Thor is does he become humble and tell his errand. Thor,

however, will not give him his daughter unless he can answer all

questions in accordance with his name, "The All-wise." Now

the interrogation begins, Thor asking the dwarf how different things, e.g.

the sun, moon, earth, are named by gods,

elves, dwarfs,

giants, and other mythical beings. The dwarf is remarkably well

informed but does not give heed to the time; he is overtaken by the

day and turned to stone before the beams of the rising sun.

11. Thor-Faith

long Prevalent. When the vigorous

priest

Tangbrand preached Christianity in Iceland, he once fell into

conversation with a heathen woman, who said to him, "Have you

heard that Thor challenged Christ to a holm-going (duel fought on a

holmr, 'islet'), but Christ dared not contend with Thor?" This

tale is significant as to our fathers' first view of the new

doctrine, and it really proved that the old ideas were preserved

among the people long after the introduction of Christianity. It was

especially difficult to eradicate the faith in the protecting and

consecrating virtue of Thor and his hammer. The sign of the hammer

and the sign of the cross were confused, indeed were even placed side

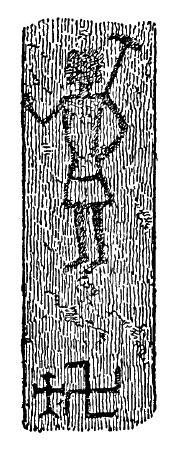

by side as sacred symbols in Christian churches (Fig. 20). In Norway,

strange to say, the common people transferred not a few of Thor's

qualities to Saint Olaf. From the Norwegian peasant's King Olaf, with

flaming red beard and with ax in hand, the sorcerer's hitter foe, to

the red-bearded thunder-god with the hammer, who crushes the giants'

and mountain giants' skulls, is a leap not nearly so great as one at

the first glance might think. But with the Christian priests, Thor

and Odin naturally stood as the worst among all the evil beings of

the heathen days; for them Christ and Thor are as incompatible as

good and evil. It is this contrast which Oehlenschlaeger firings out

in the famous conclusion of the third act of "Hakon Jarl":

OLAF.

Heaven will strike thee with its flames!

HAKON.

Thor shall splinter the cross with his hammer!

Fig.

20 Figure of Thor (?)

ODIN

1. Worship

of Odin. Together with Tyr and Thor

as well as the

goddess Frija ('the beloved,' Mother Earth), Odin

is a common

Germanic divinity, and this can be proved also by philology. Tyr's

original significance as the ancient god of heaven is, in the North,

completely obscured; the sources relate nothing particular about him

beyond that which is stated in the foregoing. Odin's name signifies

"the one blowing," and the relation here is quite the same

as in the case of Thor; a single side of the god of heaven is thought

of as a person and an independent divinity. Odin's worship is, as we

have already remarked, somewhat young in the Northern lands; but

since it permeates all Norse-Icelandic poetry, we must now look a

little more closely at Odin's divinity and the myths which are

attached to him.

2. Odin's

Appearance and Surroundings. Odin is

thought of as

an old, tall, one-eyed man with a long beard, broad hat, and an ample

blue or parti-colored cloak. On his arm he wears the ring Draupnir,

on his shoulders sit the ravens Huginn and Muninn, 'Thought' and

'Memory,' and at his feet lie the two wolves, Geri and Freki,

'Greedy' and 'Eager.' Ordinarily he is armed with the spear Gungnir,

and rides upon Sleipnir (he has many other horses; among them the

war-horse Blothoghofi), and he often travels as a wanderer around the

world with staff in hand.

Odin's

Names. If we sum up all of Odin's names in poetry, we have

more than two hundred; the most of them signify one or another

characteristic of the god: All-father, the Blustering, the

Changeable, the Stormer, the Wanderer, the Traveler, the

Gray-bearded, the Bushy-browed, the Helmet-bearer, the Great Hat, Valfathir,

'Father of the Slain,' Herfathir,

'Father of

Armies,' King of Victory, King of Spears, the Terrifier, God of

Burdens, Fimbultyr ('Mighty God'), God of the Hanged, and Lord of

Spirits (i.e. ghosts). From these examples alone it will appear that

Norwegian-Icelandic poetry represents Odin as the world's chief

divinity. But the clearest picture of him is that of God of

Wisdom

and the Art of Poetry, and in theories about Valhalla, as God of War.

3. Odin,

God of Wisdom. First of all Odin

acquired his wisdom

by personal investigation: he traveled through all countries and had

wide experience. But in other ways also he gained information, for

the ravens fly every morning out over all the world and bring tidings

back with them, and in heaven there is besides his castle Valaskjalf

or Valhalla

also a place Hlithskjalf, a

castle or simply a high seat, from which Odin can look out over the

whole world. We have already heard what sacrifice Odin was obliged to

make in order to increase his knowledge at the time when he had to

pledge one of his eyes to obtain a drink from Mimir's well of wisdom.

4. Vafthruthnir.

In the Eddic Songs about Vafthruthnir,

Odin is described as the most prominent God of Wisdom. Odin is

speaking with Frigg; he has a desire to visit the wise giant

Vafthruthnir, to test his sagacity. Frigg advises him to remain at

home, but Odin answers:

VAFTHR.

3

I

have journeyed much, attempted much,

I

have tested oft the powers;

this

I wish to know how Vafthruthnir's

household

may be.

He

departs, accompanied by Frigg's best wishes, and comes to the giant's

hall, where, under the name of Wanderer, he challenges the latter to

a contest of wisdom. First of all Odin, standing, answers the giant's

question about the steeds of day and night, the boundary river Ifing

between the countries of gods and giants, and the plain Vigrith.

Then quoth Vafthruthnir:

VAFTHR.

19

Wise

now thou art, oh guest, pass to the giant's bench

and

let ns talk on the seat together!

Wager

our heads shall we two in the hall,

oh

guest, upon our wisdom.

After

that the song rehearses a number of the main points of the belief in

the gods in questions on Odin's part; hut the giant never hesitates

about an answer, until the god asks him, "What did Odin say in

Baldur's ear before he was borne upon the pyre?" Then

Vafthruthnir understands with whom he has engaged in contest.

55

No

man knows this, what thou in early days

didst

say in thy son's ear:

With

fated lips I uttered ancient lore

and

of the downfall of the gods.

5. Grimnir.

There was once a king by name Hrauthung,

who had two sons, Agnar and Geirroth,

of whom the first

was ten, the second eight winters old. These two rowed out with a

boat to fish, but the wind drove them off over the sea, and in the

darkness of the night they were stranded upon a foreign shore. Here a

man and woman met them and cared for them during the winter. The

peasant (the man) took charge of Geirroth and gave him good counsel,

while his wife preferred Agnar. In the spring they went away in a

boat, but the peasant whispered something first to his foster-son.

When the boys came to their father's anchoring ground, Geirroth

sprang quickly ashore, thrust the boat out again, and called out to

his brother, "To the Trolls with thee!" after which the

boat again drove out upon the sea, while Geirroth went up to the

royal castle and later became an illustrious prince. The

foster-parents were, however, not poor people, but Odin and Frigg.

Now, as they were sitting one time in Hlithskjalf, Odin taunted his

wife on account of Agnar and his fortune, to which she answered that

Geirroth was, to be sure, a king, but he was so niggardly about food

that he tormented his guests in case too many came. Odin declared

this to be untrue, as indeed it was, wagered upon his opinion, and

set out in order to inquire into the matter for himself. But Frigg

sent her maid to King Geirroth and warned him against a man versed in

magic who was to come to his court and who could be known by this,

that dogs did not dare to bite him. Soon afterward a man came in a

blue cloak, and called himself Grimnir, "The

Masked";

the dogs shrank back before him, wagging their tails, upon which the

king gave orders to seize him and place him between two pyres so as

to force him to say who lie was. There he sat eight nights. Then the

king's ten-year-old son Agnar had pity on him and brought him a

filled horn to drink. Grimnir drained it, while his cloak caught

fire, after which he began to speak. Thus it is told in the prose

introduction to the Sayings of Grimnir. The poem itself contains a

number of disconnected names and myths, of which we shall quote a

single one.

6. Saga.

Odin is enumerating the dwellings of

the gods. Here

he says among other things:

GRIMN,

7

Sokkvabekk

the fourth is called, and there do cool waves

go

rushing over;

there

Odin and Saga drink every day,

cheerful

from golden cups.

This

Saga has been understood as a kind of Muse of History, since the name

has been associated with the well-known words, "a saga."

Philologists, however, have pointed out that this conception cannot

be correct. Sokkvabekk

should really be rendered 'Sinking Bench,' and Saga is doubtless a

name for Frigg, according to which the myth is an allusion to the

sunset, a poetic expression for the sun-god's meeting with Frigg,

when the sun every day sinks below the horizon westward into the sea.

Frija,

Frea in the Norse

language, grew into Frigg, one of the few Germanic female divinities

that can be pointed out. Originally she was married to the god of

heaven TiwaR,

but when Odin supplanted him he came into possession of his maid and

his wife. Furthermore, in Norse mythology, she is readily confused

with Freyja,

for which reason it is difficult to determine which myth concerns the

one or the other. It is most likely that Freyja, 'the Ruling One,'

was only an epithet of the queen of heaven and was later made into a

new divine being. Of the other names of the queen of the gods can be

mentioned Jorth,

Fjorgyn, Hlothyn.

Friday means originally Frigg's day, just as the constellation Orion

was first called Frigg's, but later Freyja's, Spinning-wheel.

7. Gefjon.

Probably Gefjon

also is originally from one of Frigg's names. In the Eddic Song Lokasenna

(the Loki Quarrel), Odin says that Gefjon knows the destiny of the

world as well as he himself. Far better known, however, is Snorri's

account of Gefjon

and Gylfi.

King Gylfi in Sweden gave her as much land as she could plow about in

one day with four oxen. She brought her four giant sons and

transformed them into plow oxen, but this team plowed so deep that

the land was loosened, whereupon the oxen drew it out westward into

the sea. It is now called Zealand, and the headlands correspond to

the inlets of the sea which remained behind in Sweden, where the land

had been.

8. The

Mead of the

Scalds. The myth

about Odin acquiring the Mead

of the Scalds has,

briefly, the following content: Scaldship

(poetry) is represented as an inspiring drink; he who partakes of it

is a Scald. It was kept at the home of the giants, where Gunnloth

guarded it. Odin makes his way through all hindrances, gains

Gunnloth's affection, and gets permission to enjoy the drink. He then

carries it up to the upper world and gives it to men.

In

the oldest and purest form the myth appears in the Eddic poem,

Havamal: "The man must be gifted in speech who wishes to know

much and to attain anything in the world. This I (i.e.

Odin)

proved at the home of the giants; it was not by keeping silent that I

made progress in Suttung's hall. I allowed the auger's mouth to break

me a path between the gray stones. The giants were going both over

and under, so it was by no means without danger."

HAV.

105

Gunnloth

gave me on the golden seat

a

drink of the precious mead;

ill

return I later let her have

(for

her faithful heart)

for

her troubled mind.

106

Her

well-gained beauty have I much enjoyed,

little

is lacking to the wise;

since

Othrerir is now come up

to

verge of men's abode.

107

Doubt

is in me if I had come again

out

of the giant's court,

if

of Gunnloth I had had no joy,

that goodly maid who laid her arm about

me.

108

The

day thereafter the frost-giants went

(to

ask of Har's condition)

into

the hall of Har;

for

Bolverk they inquired if he to the gods had come or had Suttung him

destroyed?

109

A

ring-oath, Odin, I think, has sworn:

who

shall trust his good faith?

to

Suttung deceived he forbade the drink

and

he made Gunnloth weep.

Snorri's

account embraces the following essential points:

a.

After the truce between the Aesir and the Vanir, each of them spat

into a vessel, and from this fluid they made, as a token of peace,

the man Kvasir, who was very wise. Kvasir was slain

by two

giants, Fjalar and Galar, who

caught his blood in the

kettle Othrerir and two vessels. The blood they

mixed with

honey, and from this arose the mead of the Scalds.

b.

The two giants now invited another giant, Gilling,

and his

wife to come to them. Gilling was drowned while on a sailing party,

and when his wife grieved about it they slew her. The son, Suttung,

wanted to take vengeance for his parents, but agreed to accept the

mead of the Scalds as compensation, and set his daughter, Gunnloth,

to guard it within the mountain.

c.

When Odin set out to gain the mead he came first to a field where

nine slaves were mowing grass; these were Baugi's,

Suttung's

brother's men. Odin offered to whet their scythes, and the whetstone

was so excellent that they all wanted to buy it. The god then cast it

up into the air, but all were so eager to grasp it that they killed

each other in the attempt. After that Odin, who called himself Bolverk,

proposed to Baugi that he carry on

the work of the

slaves with this as reward, that he receive a draught of Suttung's

mead. To this Baugi agreed.

d.

When the time for work was at an end Suttung, however, refused to

fulfill his brother's promise, but Bolverk thus took advantage of the

fraud: he gave Baugi an auger and made him bore into the mountain

where the drink was hidden. It was not long before Baugi declared

that the hole was through; but when Bolverk blew, he got chips in his

face, and the crafty Baugi had to bore again until the chips flew

inward. Now Bolverk proceeded into the mountain in the form of a

serpent, won Gunnloth's love, and received the promise of a drink of

the mead for each of the three nights he was there. He drained then

in three draughts both the kettle and the vessels and flew in an

eagle's form toward Asgarth.

e.

Suttung discovered this and pursued him, likewise in eagle's form.

When they drew near to Asgarth the gods set out their vessel so that

Odin might spit out the mead into it, but the giant was close upon

him and some of the mead then went the wrong way; this, which the

gods did not collect, became the portion of the rhymsters and the

poor Scalds.

REMARK.

Othrerir was perhaps at first the name for the mead of the Scalds

itself.

9. Runes.

The old world "rún" signifies

mystery,

secrecy. It was not long before the runes themselves at first

certain of them, later all of them were interpreted as magic

signs, and faith in the mighty runes has long been maintained in

popular belief and in poetry (cf. old Danish ballads). No wonder,

then, that the discovery of runes was ascribed to Odin himself. This

is distinctly told in several Eddic songs, but the real meaning is

difficult to discover.

Odin

is then also the god of all sorcery, wherefore he is called galdrs

fathur, 'Father of Magic Song,' and by the later Christian

church

in the North was regarded as the worst of the evil beings whom the

heathen worshiped.

In

the "Heimskringla" an account is given of how Odin, as an

old one-eyed man, with his broad hat, came to King Olaf Tryggvason

when the latter was at a feast at court. He talked long and shrewdly

with the king and was surprisingly well acquainted with old

traditions, with which he entertained the king even after the latter

had gone to bed. At his departure he gave the steward fat

horse-shoulders to roast for the king. In due time, however, the old

man's deception was discovered.

10. Odin

as God of Battle. "As god of war and

battle Odin

enters into the life of men. War is his work; he arouses it. He

incites kings and earls against each other. The warriors are driven

by a higher spirit. This he fosters by teaching his favorites new

means of conquering, and he himself mingles in the battle to help

them or bring them to himself (Harald Hildetann). All those who die

in arms belong to him. He gathers only nobles about him, so that

there can still be heroes when the last great battle is at hand."

Of

Valhalla, the Valkyrs and Einherjar an account has already been

given.

FREY

AND NJORTH

1. Worship

of Frey. The third chief divinity

among the people

of the North, about whose worship we have definite information, is Frey,

who, however, cannot with certainty be

pointed out as a

general-Germanic divinity and whose nature and origin therefore are

difficult to determine. The name signifies The Ruling One.

The

corresponding feminine form is Freyja, 'The

Mistress,' whose

name heretofore was preserved in Danish in the word Husfrǿ, which

later through German influence became Husfru and

after that

was changed to Hustru, 'wife.' The general

mythological

details about Frey have been given above, where too his significance

as the supposed ancestor of the Swedish race of kings is indicated.

The Ynglings in Sweden descend, according to an old

Scaldic

lay, from Yngvi-Frey. Through this name we can perhaps trace a.

connection with Germany, since the Latin historian Tacitus in his Germania

names three chief Germanic races, of

which one was

the Ingvaeones. In any case Frey is originally a

variation of

the god of light and heaven. He himself is called The Shining One,

God of the World, and Chief of the Gods. He lives in Alfheim; his

boar is called Gullinbursti, 'golden bristles,' his

attendant Skirnir, 'Maker of Brightness,' and he is in

possession of

treasures which only the most prominent god can own.

According

to the Volva's Prophecy he contends in Ragnarok

with Surt.

There he is called Beli's Blond Destroyer. Beli

is

brother of the giantess Gerth and one of the finest

of the

Eddic poems, Skirnismal, Skirnir's Journey,'6 deals

with Frey's love for Gerth.

2. Skirnir's

Journey. Skirnir is Frey's

attendant but also

his friend from youth up. Wherefore he is quite accustomed to being

the god's confidant. One time something was troubling Frey, for he

seated himself apart without wishing to speak with any one. Skathi

then bade Skirnir ascertain what had awakened the strong god's wrath,

and Frey answered:

SKM.

6

In

Gymir's court I saw walking

a

maiden dear to me;

her

arms shone and from them too

the

air and all the sea.

7

A

maid dearer to me than maid to any man

youthful

in early days;

of

Aesir and of elves this no one wishes

that

we should be together.

In

the prose introduction to the poem it is related that Frey had seated

himself in Hlithskjalf and had looked out over all the world. He had

also cast eyes upon the fair Gerth, daughter of the giant Gymir.

Skirnir

offers now to ride to Jotunheim as a suitor for his friend, provided

the latter will lend him the steed which will bear him most safely

through the dark, flaming magic fires, and the sword which swings

itself against giants and trolls. This is done, and after a dangerous

and intricate ride the swift Skirnir stands in Gymir's hall in

conversation with Gerth. Without circumlocution he tells his errand;

first he promises her eleven golden apples, next, the ring Draupnir,

provided that she will give Frey her love. He is however refused on

both scores, for "gold is cheap in Gymir's court; I have the

disposition of my father's wealth." Then Skirnir resorts to

threats: he will strike her father down and slay her with the

rune-written sword; with the magic wand he will subdue her and send

her as booty to the cruel troll-people of the underworld.

SKM.

33

Wroth

with thee is Odin, wroth the most excellent of gods,

thee

shall Frey hate;

Most

evil maid! (thou) who hast attained

the

gods' ferocious wrath.

34

Hear

ye giants, hear, frost-giants,

ye,

Suttung's sons,

(ye

gods too)

how

I forbid, how I deny

to

the maid the joy of men

to

the maid the pleasure of men.

The

maid who can reject the bright, beaming god's affection shall be

punished by becoming Hrimgrimnir's bride down in the death-realm.

Thither shall she totter every day, broken in will and without

volition, partake of the most loathsome food and live her life under

the most gruesome conditions. Not until now does the stubborn maid

submit, terror-stricken.

38

Hail

(now rather), youth! and take the crystal cup

full

of ancient mead;

vet

I have ne'er believed that e'er I should

love

well a Vanir's son.

But

Skirnir wishes to have full information and Gerth answers then that

in nine nights, in the grove Barri, she will

celebrate her

bridal with Frey. Then Skirnir rides back to the latter and tells him

the result of his journey. The poem ends with Frey's declaration of

his inexpressible longing for the bride.

3. Frey-Njorth.

It is well understood that

there is a

definite connection between Yngvi-Frey, Freyja, and Njorth, but the

original relation has not been successfully determined. Both Njorth

and Frey in Norse mythology are gods of fruitfulness and have about

the same characteristics. The most of these are found also in Freyja.

Tacitus mentions in connection with a North German tribe a female

divinity Nerthus, and with this name the Norse word Njorth

exactly agrees as a masculine form. Upon on island in the ocean was

her sacred grove, with a consecrated wagon which only the priest

might touch. In this wagon drawn by cows, the goddess in solemn

procession and amid the exultation of the people was led about on

festal days. Then peace and joy prevailed. Before the goddess was

taken back to the temple, the wagon, the garments, and the divinity

herself were washed in the sacred lake.

REMARK.

The tale about Hertha and her worship at Lejre

(in

Zealand) is only a late tradition which is founded on a perversion of

Tacitus' account, and does not belong among the heathen beliefs.

HEIMDALL

AND BALDUR

1. Heimdall

is a purely Norse divinity and must

according to his

name and peculiarities be, like Frey, a manifestation of the god of

heaven and light, perhaps more definitely the god of the morning red,

the day's gleam which shows itself at the horizon immediately before

the rising of the sun. The name means "he who lights the world."

His steed is called Gulltopp. An account has been given above of his

dwelling and employment. The Volva's Prophecy begins with the

following words:

VSP.

1

Hear

me all ye holy kindred,

greater

and smaller, Heimdall's sons!

That

men are here called Heimdall's sons is not necessarily an outcome of

an ancient conception of Heimdall as supreme god. This expression

comes rather from an Eddic song which is somewhat older than the

Volva's Prophecy, in which the god, under the name of Rig,

is

represented as the ancestor of the different classes of society.

2. Rig

is a Celtic word which means prince or

king. Long ago the

wise god, strong and active though advanced in years, wandered along

green paths until he came to the hut in which great grandfather and

grandmother, Ae and Edda,

dwelt. He took a situation

with them, gave them good advice, and partook of their heavy coarse

bread and soup. He remained there three nights and sought rest

between them. But nine months afterwards Edda bore a child, which was

baptized with water and received the name Thraell.

He had a

furrowed skin, long hands, an ugly face, thick fingers, long heels,

and a stooping back; but he became great and strong and capable for

work. Later he married Thir, "a thrall," and from the two

descended all the Thralls.

Rig

wandered farther along the road and came to a hall which grandfather

and grandmother, Afe and Amma,

owned:

RIGSTH.

15

The

couple sat there, were busy with their work;

the

man was hewing there wood for a weaver's beam;

his

beard was trimmed, a forelock on his brow,

shirt

was close fitting, a chest was in the floor.

16

The

woman sat there, turning her distaff,

stretched

out her arms, made ready the cloth;

a

coif was on her head, kerchief on her breast,

a

scarf was at her neck, clasps upon her shoulders.

Filled

dishes and cooked veal were set upon the table. Rig ate and remained

there three nights, and nine months later Amma bore a son, who was

baptized and called Karl.6

He tamed oxen, forged

tools, built houses, and tilled the ground. His wife was called Snor,

and their progeny was the race of free peasants.

Rig

continued his wandering until he reached the hall of father and

mother, with the door towards the south, a ring in the door-post, and

the floor covered.

RIGSTH.

27-8

The

householder sat twisting his bow-string,

Lending

the elm-bow, fitting the arrows,

But

the housewife was observing her arms,

stroking

her dress, drawing tight her sleeves,

her

cap set high, medallion on her breast,

had

long trained-dress and bluish sark.

The

mother laid a white-figured cloth upon the table and set on fine

wheat bread.

31

She

set dishes silver-plated on the table,

well

browned bacon, roasted fowl;

wine

was in the tankard, the cups were of line metal,

they

drank and talked, the day was nearly done.

But

afterwards mother bore a son who was swaddled in silk, baptized, and

named Jarl. "Light were his curls, bright his

cheeks,

sharp as a serpent's his shining eyes." Jarl from childhood had

practice in arms. Rig came to him, taught him runes, called him son,

and gave him great riches. Erna became his wife, and they had many

valiant sons, of whom the youngest was Kon ungi

('Kon the

Young,' hence Konungr, the word for "king"). He was

a glorious hero and vied with or surpassed Jarl both in arms and in

shrewdness. Finally he set out for adventure in order to gain

celebrity and a fair bride in Denmark. The poem consists here of

incomplete fragments only, yet we hear that

RIGSTH.

38

The

shaft he shook, he swung his shield,

his

steed he urged, he drew his sword;

strife

he did awake, the field he reddened,

warriors

he felled, gained land in war.

The

Lay of Rig contains undoubtedly a glorification of kingly power and

is supposed to have been composed in Norway in praise of an absolute

king (Harald Harfagri?7).

3. Baldur.

The myth of Baldur, the most

disputed of all the

myths, is also distinctly Northern. Baldur is commonly understood to

have arisen, like Frey and Heiman, from an embodiment of an original

epithet of the old god of heaven. Bugge, on the contrary, maintains

that the theories about Baldur are formed from a combination of Irish

legends about Christ and misunderstood Greek and Roman tales. This

view, however, encounters great difficulties, and strong opposition

to it has arisen. (See Introduction.)

4. Two

Baldur Myths. Besides allusions in

several Eddic

songs, we find the Baldur myth in various forms in Snorri and Saxo.

Both in Denmark and elsewhere in the North, place-names are found and

local traditions which are connected with Baldur. The plant-name

"Baldur's brow" also is an evidence of the faith in this

god.

The

substance of the myth is the same in Snorri's and Saxo's

representations: Baldur is a son of Odin and Frigg; he is slain by

Hoth but is avenged by his brother. Hoth signifies "combat"

and agrees closely with the form Hotherus in Saxo,

who,

however, calls the avenging brother Bous, the Vali

of

Icelandic sources. In Saxo the contest turns upon the princess Nanna,

King Gevar's daughter, who is loved by the Shielding8

Hother, while with the Icelanders she is the god Baldur's wife, and

Hoth is his blind brother. In Saxo there are preserved indistinct

traits of the Valkyrs (the three Forest Maids) and of the murderous

sword which is kept by the giant Miming. We must also remark that as

Baldur is everywhere a son of Odin, the information about him must at

all events be later than the rise of Odin faith and is therefore of

comparatively late development.

5. Baldur's

Dreams. In addition to all we have

alluded to

concerning Baldur in the preceding section we will now recount a few

Icelandic myths about this god.

Since

evil dreams had given warning of danger to Baldur's life, Odin rode

upon Sleipnir down to Helheim to the burial place of a wise sibyl.

With powerful incantations he conjured up the dead and asked her for

news from the underworld; in return lie agreed to tell her about

earth and heaven. He wants to know why such festal preparations are

being made in the hall of Hel: the floor is spread with straw, the

benches strewn with rings, and the wagons filled with clear drinks

and covered with shields. The sibyl confirms his gloomy forebodings:

it is Baldur's coming that they await. This is the chief content

of the Eddic Song of Vegtam9; but the conclusion

of the

poem is incomplete and unintelligible.

6.

Baldur's Funeral. The .Aesir took Baldur's body and carried

it to the sea. Hringhorn was the name of Baldur's

ship, the

largest among all ships. The gods wished to push it out and make

Baldur's funeral-pyre upon it, but the ship could not be moved. They

then sent a messenger to Jotunheim for a sorceress who was named Hyrrokin.

She came riding upon a wolf and had

a viper for a

bridle. Four Berserks were to guard the wolves, but they could not

hold them until they had thrown them down. Hyrrokin went to the bow

of the ship and pushed it out with the first thrust, so that fire

went out from the rollers and the whole country trembled. At that

Thor became wroth, grasped the hammer, and wanted to crush her head,

but all the gods united in saving her by their intercession. Now

Baldur's body was borne out upon the ship. When his wife Nanna saw

this, her heart broke from grief and she was laid upon the pyre with

her husband. Thor next stepped forward and consecrated the pyre with

the hammer. A dwarf ran before his feet and Thor in his rage kicked

him into the fire, where he was burned. Many gods and giants were

present at the funeral. Odin laid the ring Draupnir on Baldur's

breast, and the god's horse was led out with all his trappings.

7. Hermoth's

Hel-Ride. After Baldur's death,

Odin's son,

Hermoth the Swift, took it upon himself at Frigg's request to ride

down to Hel to beg release for Baldur. He saddled Sleipnir and rode

nine nights and days through dark and deep dales; he could not see a

hand before him, until he came to the river Gjoll

and out upon

Gjallar Bridge, which was covered with bright gold. Mothguth,

was the name of the maid who watched the bridge. She asks him for his

name and race and says that the day before there rode five companies

of dead men over the bridge, "but not less does the bridge

resound under you alone; you have not the color of dead men; why do

you ride hither upon the Hel-road?" Hermoth asks if she has seen

Baldur; she answers in the affirmative and shows him the way: "down

towards the north goes the Hel-road." Now Hermoth rides farther,

until he comes to Hel's grated gate. He dismounts from his horse,

girds him fast, mounts again, gives him the spurs, and the horse

leaps over without touching the gate at all. Then Hermoth rides on to

the hall and goes in. He sees his brother Baldur sitting in the high

seat, but remains there over night before he discharges his

commission. At his departure Baldur sends gifts to Odin. How the

test of weeping failed has already been told.

8. The

Death-Realm. The narrative about

Hermoth's Hel-ride

deviates widely from Snorri's descriptions in various places of the

realm of death and the goddess of death, but contains certainly an

older and more original conception. Hel means "the concealing

one." She is a queen and dwells in splendid halls which are

decorated like a royal castle on earth, for the floors are strewn and

the benches covered with carpets and expensive materials. Dead men

(but neither those dead of disease nor cowards) ride

to Hel in

warlike hosts and all equipped, and their king takes his place on the

high seat which is prepared for him. Conceptions of Hel as a place of

punishment are not at all definitely indicated in the oldest poetry,

yet on the contrary a Nifl-Hel is named "to which

men die

from Hel." The oldest belief seems to have comprehended three

worlds (although the Volva's Prophecy tells of nine): the land of the

Gods, the World of Men, and the Realm of the Dead (heaven, earth, and

the underworld, possibly with a hint at a place of punishment,

Nifl-hel). But when the Odin-cult and with that the belief in

Valhalla first made its way into the popular consciousness, men

thought that the brave went to Valfather, the cowardly, and those

dead of disease to Hel. Then Hel became Loki's daughter and her realm

a counterpart of Valhalla.

Hel,

according to Snorri's representation, gained sway over nine worlds in

Niflheim. Her kingdom is called Helheim, which is

reached by

the Hel-road, over the Gjallar Bridge, past the Hel-gate or death

boundary. The Hel-hound, Garm, runs out of the Gnipa-cave. The

death-goddess herself, horrible to behold, is upon her throne in the

hall Eljuthnir, her maid is Gang-lot,

her threshold is

called "falling deceit" and her couch is the "bed of

sickness." The word Hel is even now preserved in the Danish

words ihjel, 'dead'; Helved,

'hell'; Helsot,

'fatal disease'; and Helhest, 'hell-steed.'

Likewise the

widespread superstition that the howling of dogs presages death is

probably a half-extinct reminder of the Hel-hound.

LOKI

1. Loki.

We have now remaining one of the most

enigmatic

figures within the circle of Norse gods, the one who bears the name Asa-Loki,

although it is often recorded that

he originally

belonged to the race of giants. Many explanations have been given of

the meaning of the name, and just as many of the origin and meaning

of the god himself. It is most probable that Loki signifies "the

one closing, bringing to an end," and in order to understand his

nature we will begin with his own words in the old lay, The Loki

Quarrel:

LOK.

9

Dost

remember, Odin, when we in early days

did

mingle blood together?

Taste

ale you never would, you vowed,

unless

'twere borne to both.

Loki

is accordingly Odin's foster-brother and in the most intimate and

cordial relation to the chief divinity possible between two men. He

has also many of Odin's noble qualities, but his temper is such that

he is not capable of exercising them in the right way. He has sense

and understanding like Odin, but they express themselves in bitter

malice and fraudulent acts. He is as strong in merits as in faults,

but the latter gain more and more control. Odin's foster-brother,

Asa-Loki, must therefore become finally the worst enemy of gods and

men, who also at Ragnarok takes a commanding position among the evil

powers in the destruction. Hence he is endowed in the later

mythological poetry with one evil trait after another. With Angrbotha

he begets the frightful trio, and since he also occasions Baldur's

death, it is with a certain right that he has been called the "devil

of the North." On the basis of his relation with the

storming heaven-god, Loki might properly be regarded also as the god

of fire, and for this a strong argument may be found in the

narratives about him. Fire is the benefactor of the human race, but

also its merciless enemy. Thus Loki becomes the opposite of Heimdall,

and with him he fights the last battle at the crisis of the gods,

just as he previously at Singasten had fought with him for Freyja's

necklace, Brisingamen.

2. Seizure

of Ithun. One time the three Aesir,

Odin, Hoenir,

and Loki, traveled from home over fields and desolate lands where

they could find no food. First, down in a valley, they found a herd

of oxen, of which they killed one and sought to cook it over a fire;

but the flesh would not become tender, however much they cooked it.

This was caused by an eagle which was sitting in a tree above them,

and which said it must have its full share of the ox should the

cooking succeed. The gods promised this, but when the meat was cooked

the eagle took both thigh and shoulder for his part. In exasperation

at this, Loki thrust at him with a rod, but the rod remained fast in

his body and Loki was unable to loose his hold on the other end. The

eagle flew rapidly and high; Loki's limbs were almost torn from him

before lie yielded. It was the giant Thiazzi in eagle's form who had

borne him away. For his freedom he was now obliged to promise to

entice away Ithun with the Aesir's old-age remedy (the Apples), so

that the giant could seize her. At the time agreed upon Loki coaxed

Ithun out into the wood with her apples, in order that she might

compare them with some others that he claimed to have found. The

giant then came up in eagle's form and flew away with Ithun.

But

when Ithun was away the Aesir soon turned gray. Ithun was last seen

together with Loki, and the latter in order to save his life had to

confess everything and promise to restore the goddess to Asgarth. In

Freyna's falcon-cloak he flew rapidly to Jotunhehn, found Ithun at

home alone, transformed her into a nut, and flew away with her in his

claws. Shortly afterwards Thiazzi came back and missed Ithun. In

eagle's form he pursued the robber, who, however, escaped over

Asgarth's walls, behind which the gods had kindled a great fire. With

scorched wings, Thiazzi sank to the earth when he could not stop his

mad flight, and was slain by Thor.

3. Skathi

in Asgarth. Thiazzi's daughter Skathi

now put on

full equipment and proceeded to Asgarth to take vengeance for her

father. Meanwhile, to reconcile her, the gods offered to allow her to

choose for herself a husband from their number; but she was to choose

according to the feet alone, for the body and head she was not

allowed to see. She chose then a man with very handsome feet, in the

belief that it was Baldur, but it proved to be Njorth. Their

experience has already been related. Skathi was even now not

satisfied and demanded that the gods should make her laugh. No one

was able to do this but Loki, at whose wanton jests she could not

keep serious. As additional penalty Odin (or Thor) took her father's

eyes and cast them upward to heaven, where they were transformed into

stars.

4. Loki

Scoffs at the Gods. Loki's worst

offense was this,

that he caused Baldur's death; but as we have seen, he had time and

again defied the gods before. He offered them the greatest disdain at

the feast which the sea-giant Aegir instituted for the Aesir and for

which Thor had brought the great kettle from Hymir. All the gods and

goddesses were present with the exception of Thor, and Loki also took

part in the feast. Aegir's two servants received much praise for

their swiftness, but Loki was provoked at this and struck one of them

dead, after which he was driven out. Some time afterwards, however,

he returned to the hall and now began to scoff at the gods and

goddesses, the first with mockery and sarcasm, the latter with

venomous words in which he charged them with a lack of chastity. Some

sought to quiet him, others retorted, but all in vain. He stood there

in the midst of the hall as the Aesir's evil conscience. To be sure,

he exaggerated strongly; but there was a grain of truth in all he

said, and therefore they all sat there well-nigh distracted. At last

Sif, Thor's wife, became the object of his scoffing. Then they called

on Thor, and the strong god stood there in the hall brandishing his

strength-hammer; three times Loki ventured to defy Vingthor, but when

the latter the fourth time threatened him with death, he fled:

LOK.

64

I

spoke before Aesir, spoke before Aesir's sons,

that

which my mind did prompt me;

but

before thee alone, shall I go out

since

I know that thou dost strike.

Such

is the main content of the Edda-song of Loki's Quarrel (Lokasenna).

_________________________________________

1

Or Defender.

2

Necklace.

3

Tors Rejse til Jotunheim.

4

Nor dens Guder.

5

Indicated by the title For Skirnis often used.

6

Free man.

7

Harald Fairhair, king of Norway, 860-933.

8

Shieldings. Icel. skjoldungar, litt 'sons of Skjold,' came to mean

'princes,' 'kings.'' Heathen kings of Denmark were meant.

9

Vegtamskvitha.

|