| GENERAL

INTRODUCTION

1.

By "Norse mythology" we mean the information we have

concerning the religious conceptions and usages of our heathen

forefathers, their faith and manner of worshiping the gods, and also

their legends and songs about the gods and heroes. The importation of

Christianity drove out the old heathen faith, but remnants or

memories of it long endured in the superstitious ideas of the common

people, and can even be traced in our own day.

There

has never been found on earth a tribe of people which did not have

some kind of religion, but the lower the plane of civilization on

which the people are found, the ruder and less pleasing are their

religious ideas. Religions consequently change and develop according

as civilization goes forward. One can, therefore, learn much by

knowing the mythology of a race, since it shows us what stage the

people in question have attained in intellectual development, what

they regard as highest and most important in life and death, and what

they regard as good or evil.

Sun-worship

and Nature-worship. — We can easily perceive that a belief in

counseling and controlling gods presupposes a far higher civilization

than savage people in their earlier history possess. Religious ideas

proceed partly from soul belief, belief in the continued life of the

soul, and partly from the belief that nature is something living,

peopled by mysterious beings which control regular and irregular

changes in nature upon which man feels himself dependent. Such beings

are often designated by the Greek word Demons. These

nature-demons make themselves plainly known through the roaring of

the storm, the rippling of the water, or the wind's gentle play with

the tree-tops. But races in the childhood period of their development

cannot hold fast to a belief in life apart from bodies. Demons,

therefore, are thought of in bodily form — as men or beasts. At the

same time man feels his helplessness and powerlessness in the

presence of Nature and its mysterious forces; he is prompted, then,

by offerings and supplications to gain friendly relations with these

powers which he with his own strength cannot over- come. In this we

begin to find the first germ of divine worship which is capable of

subsequent development, since ever increasing domain is 'given to the

single demon. With the advance of civilization there is developed in

the place of the belief in demons a belief in mighty gods, who are

thought of as beautiful and perfect human forms.

Greek

and Norse Mythology. — With the more developed heathen people

there is always an exact correspondence between the nature of the

country, the character of the people, and their religious belief.

There is, therefore, a striking distinction also between Greek and

Norse mythology. The Greek is bright and pleasant, like the country

itself; the gods are thought of as great and beautiful human forms

who are extolled not merely as gods, with offering and worship, but

also as inspired Greek artists and poets, producers of statues and

songs, the equal of which the world has scarcely seen. Norse

mythology as we know it from the latest periods of the heathen age

is, on the contrary, more dark and serious, and when it lays the

serious aside it often becomes rude in its jesting. Norsemen felt the

lack of talent for the sculptor's and painter's art, although they

were really clever in carving wood; their idols were as a rule merely

clumsy wooden images embellished in various ways. Their religious

faith, on the other hand, has called forth poetry which in its way is

by no means inferior to the Greek; and our forefathers' view of death

and particularly their teaching about Ragnarok, concerning which we

shall speak later, can rightly be preferred to the Greeks' faith in a

miserable shadow-life in a realm of death (Hades).

Why

We Teach Norse Mythology. — For us Norse mythology has in any

case the advantage of being the religion of our own forefathers, and

through it we learn to know that religion. This is necessary if we

wish to understand aright the history and poetry of our antiquity and

to comprehend what good characteristics and what faults Christianity

encountered when it was proclaimed in the North. Finally, it is

necessary to know the most important points of the heathen faith of

our fathers in order to appreciate and enjoy many of the words of our

best poets. This is especially true concerning Oelenschlaeger and

Gruntvig, who not only have embodied large parts of the Norse

mythology in independent poetic works (as "The Gods of the

North," "Earl Hakon," "Scene from the Conflict of

the Norns and Acsir") but also often borrow from it in their

other works terms and figures which we ought to be able to

understand. To point to the antiquity of the North and to our

fathers' faith, life, and achievements was one of the poet's

principal means of awakening the slumbering national feeling at the

beginning of our century.

2. Oldest

Inhabitants of the North. — It is possible that it

was our ancestors who, several thousand years before the Christian

era, inhabited Scandinavia, in the stone age. Learned investigations

have in every case proved as most probable and reasonable that people

of the bronze age, both before and after the year 1000 B.C., belonged

to the same race as the Northmen of the iron age, so that our heathen

era stretches over a space of at least two thousand years. We must,

therefore, seek information about the

oldest

religious ideas of the North in prehistoric archeology, the science

which investigates and throws light upon every species of relic

preserved from antiquity. Here it is especially burial rites and the

placing in graves of objects supposed to be offerings which have

mythological significance.

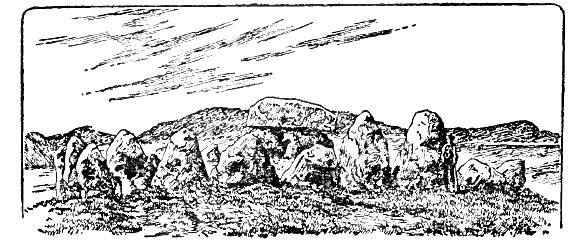

Fig.

1 — Round Burrows

a.

In the remains of the earliest stone age, the refuse heaps, no burial

places have been discovered; but from the latest stone age have been

found a great number of graves, round and long barrows, sepulchral

chambers (Figs. 1-3), and stone "chests," in which bodies

were laid unburned and supplied with the necessary implements, which

shows a belief in a continued life after death. Burned places and

remnants of pyres in the graves seem to indicate

offerings

to or for the dead, and hewn in the stones are often found certain

saucer-like depressions, wheels and crosses, which most likely have

religions significance (Fig. 4).

b.

In the bronze age, which ends some hundred years before the birth of

Christ, men long preserved burial rites from the stone age. Bodies

were not burned, but were placed in raised mounds in a tightly closed

stone setting or in chests of hollowed trunks of oaks. Later,

however, the burning of bodies became more and more common; ashes

were preserved in stone vessels or most often in clay urns within the

mounds; many times use was made of old mounds from the stone age. The

greatest number of our barrows contain, therefore, tombs from the

bronze age (Figs. 5-7). The reason for this change in the mode of

burial seems to be the rise of new ideas about life after death. At

first people believed in a continued life of the body, later they

burned the body to set free the soul. Likewise in the stone age men

deposited in the graves sacrificial gifts, handsomely wrought objects

for use or ornament, For decoration are used now also hooked crosses

and trefoils (Figs. 8-9). These emblems, whoa significance is not

known, are found used as sacred tokens ("religious symbols")

among all Indo-European peoples.

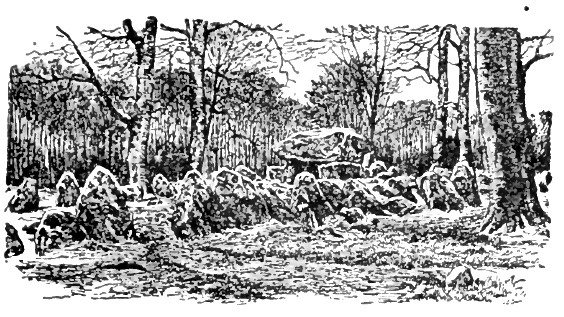

Fig.

2 – Long Barrows.

c.

The iron age begins probably sometime in the fourth century B.C. In

very ancient times; even, the Northmen had enjoyed commercial

relations with Asia and Greece. From about the time of Christ's birth

there begins a strong Roman influence, which, among other things,

gives the Gothic-Germanic people a peculiar alphabetic writing, the

Runes. The iron age stretches even into historic times; the last

division is the Viking time (c. 800-1000). In the course of the iron

age people again stopped burning bodies, since, as Snorri says, the

cremation-age was succeeded by the mound-age. Bodies were once more

regularly provided with objects for use — weapons and vessels for

food and drink. Discovery has been made of large and splendid

offerings (e.g. golden horns), urns with slain animals,

perhaps even altars upon which rude images1 of the gods

seem to have been raised (Fig. 10). Several other things from the

middle-iron-age will be touched upon in what follows; but we do not

see anything really definite, indicating belief in gods, until far on

toward Viking times.

3. Common

Norse Language. — At the beginning of the Christian

era, the Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes constituted but one tribe,

speaking the same language, Urnordisk, Primitive Norse. This

common language was preserved, with a succession of natural

transitions and changes, to be sure, to about the year 1000. In

Viking times this was called den danske Tunge, "the

Danish Tongue," and from it the separate Norse languages have

gradually been developed. It is also probable that the Northmen had

the same heathen religion in all the main points; even in the worship

of the gods there has been but little difference in the different

provinces.

Gothic-Germanic

Race. — We may even go a step farther back, for it can be

established in many ways that Northmen, Germans, and Englishmen also

were once one great race, which is usually called the

Gothic-Germanic, and this Gothic-Germanic race has again a common

origin with most of the European peoples (e.g. the Greeks),

and with the inhabitants of Persia and India.

Indo-Europeans.

— We must then picture to ourselves a "primitive people"

whose original place of abode we cannot determine, but from which

these related peoples have through long periods been developed. This

primitive people as a matter of course had certain religious ideas,

and it is probable that we may be able to find traces of the original

divine faith in the Indian, Greek, and Norse mythology; and this is

actually the case. The linguists who are occupied with comparisons

between the languages of the different Indo-European races have been

able to establish many such points, but here we must be content with

bringing forward a few examples.

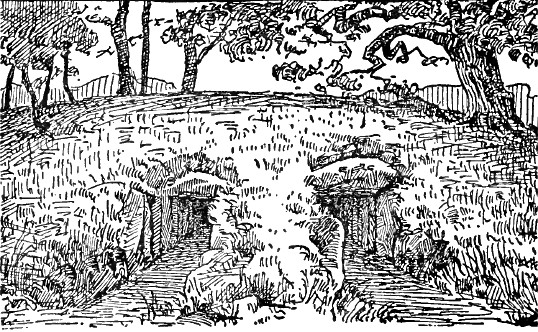

Fig.

3 – Sepulchral Chambers, or Cairn.

Aesir.

— The general name for the gods was, among the Northmen, Aesir,

which is developed from the older Anser. Corresponding forms

are found in most of the related languages. The Heaven-God was called

among the Indians Dyâus, by the Greeks Zeus, by the Romans Ju-piter.

The Germanic people believed in a god whom they

called Tiu while there is found in the Norse religion the name Tyr

(preserved in Dan. Tirsdag, Eng. Tuesday). In the

oldest

Norse language this word must have been TiwaR.2

But all these names undoubtedly spring from a common basal form,

which signifies "the bright one" or "the shining one,"

and which consequently may have designated the god of the heaven or

the sun.

Tyr,

Odin, Thor. —

Gradually, as the Indo-Europeans scattered and in the course of time

settled in different regions with greatly differing climate, they

gave to their god of heaven many epithets, according to the nature of

the country in which they had settled. The Gothic-Germanic people

called him now by the original name, now Wothanar or ThonaraR

("the blowing one," "the thundering one"), and it

was not long before they forgot that these names were only appendages

to the old heavengod's name. Now they enumerated as many gods as

there were names, and thus arose, among other things, belief in the

three divinities, Tyr, Odin, and Thor. (The Germans said Wodan and

Donar. In the North we have little or nothing of the worship of Tyr;

Frey takes the place of this god.) Consequently new divinities and

new religious ideas seem to have arisen among our forefathers

according to the rule that

the god's epithet or title is separated from his name and then

designates an independent personal being.

Since this is applicable to a god, one can easily imagine that

something similar can be the case with many other points in

mythology.

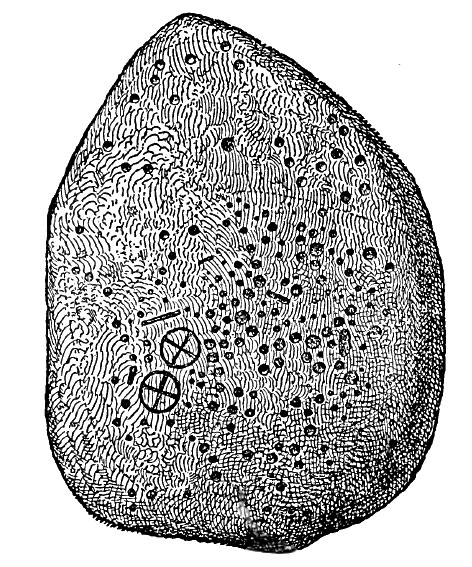

Fig.

4 – Stone with Saucer-like Depressions, Wheels and Crosses.

Common

Myths — But a direct comparison also between the heathen faiths

of the Indo-European people shows that many single points in their

religions (myths) correspond. Myths about a world-tree are

found among both Indians and Northmen. The highest god among the

Indians. Greeks, and our forefathers alike is armed with a

sure-striking missile in his capacity of the thunder-god, whether

this he represented plainly as a thunderbolt (lightning-flash), a

hammer. or a club.

Cæsar

and Tacitus — Besides this we know but little with certainty

about particular points in the mythology of the oldest

Gothic-Germanic people; and so it is also with regard to the religion

of the Northern people in the first centuries of the Christian era,

for they have left no written records behind them. We have already

spoken of what we can learn from ancient finds, not a few important

points of information, especially the latter in his historical books

and in his brief account of Germany.

Fig.

5 – Coffins from the Bronze Age.

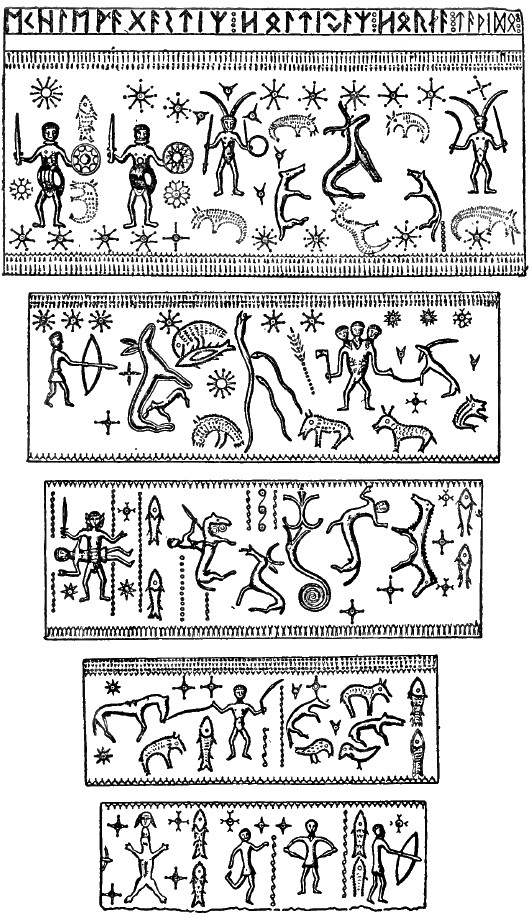

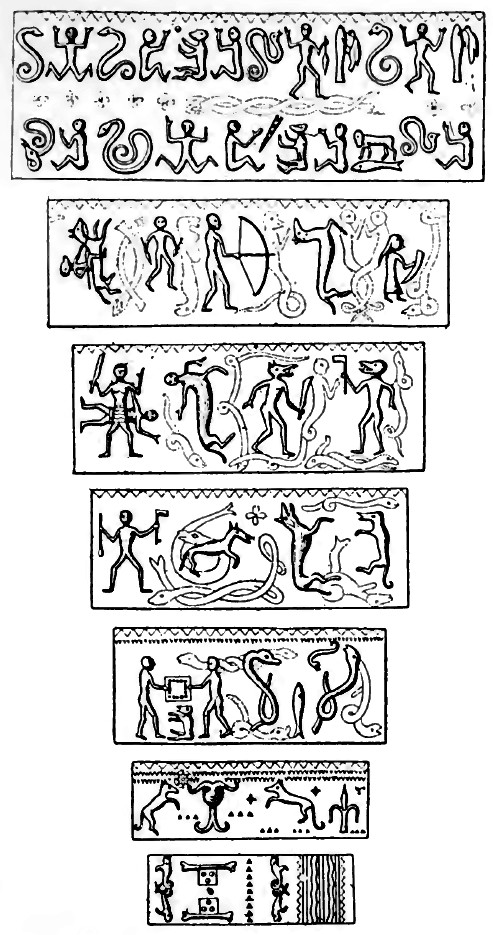

4. Runes.

— But about the third century after Christ the

Gothic-Germanic people soon reached also the Northern races, where

they were scratched upon objects in common use, as combs, clasps,

weapons, and drinking or sacrificial horns. Here belong the

aforementioned golden horns from Gallehus in southern Jutland. These

were found in 1639 and 1734 and had a value in our money of about

17,000 kroner ($4,760). At the very beginning of our century they

were stolen on account of their great value and melted over, so we

now must content ourselves with drawings and casts of these splendid

monuments of antiquity, which may have been a sacrificial gift. They

consisted of two smooth golden horns of very fine gold with an outer

casing of tight-fitting rings likewise of gold, on which there were

engraved figures and ornaments, and between these again there were

raised figures firmly soldered (Figs. 11-13). Many attempts have been

made to interpret these pictorial representations, which easily have

a religious significance. Worsaae, our renowned archæologist, was of

the opinion that one horn represented life in hell (the serpents),

the other life in Valhalla (the stars), which however is wholly

uncertain. Along the uppermost ring of one horn one may read in the

primitive Norse language:

ek

hlewagastiR

holtingaR

horna tawido,

that

is: I, Lægtæst, Molt's son (or, from Holt), made the horns.

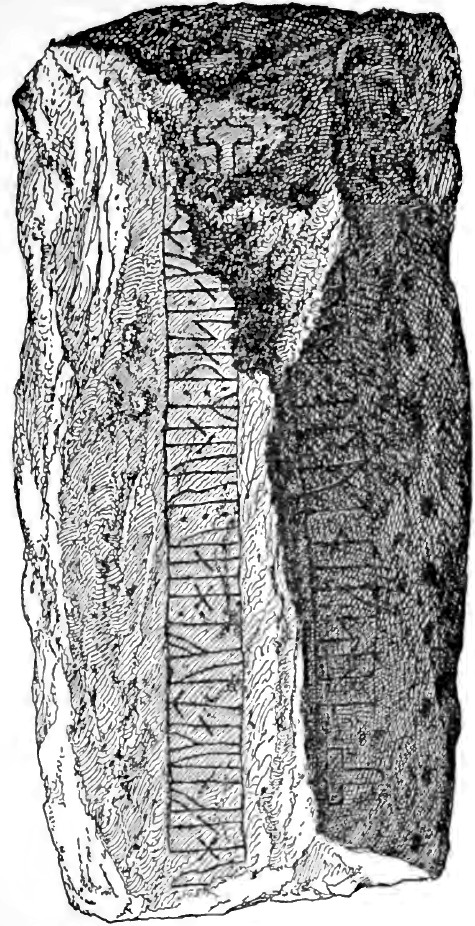

Rune-Stones.

— Somewhat later men began to use runes for inscriptions on

bowlders, which were placed in or oftenest upon grave mounds or

elsewhere, as memorials for the departed. Such rune-stones are found

in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from different ages, but with us Danes

only from epochs between 800 and 1070,3 the oldest

therefore even from the heathen time. Rune-stones give the

earliest and surest contribution to our knowledge of Aesir-faith in

the North.

Fig.

6 – Grave Mound with Urns.

Thor

on Rune-stones. — On the Glavendrup stone from about 900, which

contains the longest Danish runic inscription, we read, after the

memorial words themselves, the following:

May

Thor consecrate these runes!

On

another Danish rune-stone the invocation comprises the whole

memorial, for on the margin of the stone is engraved:

May

Thor consecrate this monument!

Such

a place consecrated or dedicated to the gods is called a Ve or Vi,

which name we have preserved in Odense (i.e.

Odinsve) and Viborg. On the Glavendrup stone, which is raised over

the Chieftain Alle, the latter is called "Vierne's honorable

servant," and on a south Jutland rune-stone Chieftain Odinkar's

daughter calls herself Vi-Asf rid.

Thor

the Chief God. — Only on these two stones is the name of the

god of thunder expressly given, but on others we find engraved

trefoils, quatrefoils ("hooked crosses"), or hammers (Fig.

14), which is an evidence of the fact that Thor at this time was

the chief god of the Danes; and this same thing we can establish

in many other ways, and for the rest of the North also. This is shown

by the many compound person and place names in which Thor's name is

the first member (e.g. Thorsteinn, Thorbergr). Finally, it can

be emphasized that when the Gothic-Germanic people translated the

Latin names for the days of the week, in the fifth day, which in

Latin is called Jupiter's day (dies Jovis), they translated

Jupiter by Thor (Icel. Thorsdagr, Dan. Torsdag,

Ger. Donnerstag).

Fig.

7 — Row of Grave Mounds.

Odin

and Frey. — Together with Thor, Odin and Frey were especially

worshiped, and some evidences of this fact are found upon

rune-stones. Odin, however, was not understood as the mighty supreme

god among the common people. He is so represented only in

Norwegian-Icelandic poetry, and it was among the Germanic people

dwelling southward that Odin-worship played an important part at an

early period.

5. Iceland.

— There are, therefore, but few details known to

us

of our forefathers' religion at the beginning of Viking times. But

from about the year 900 and later we have full and rich information

about the religious ideas of the Northern people in the

Norwegian-Icelandic literature.

|

|

| Fig. 8 – Quatrefoil or

Hooked Cross. |

Fig. 9 — Trefoil |

Mythological

Poetry. — When different families of the Norwegian nobility at

the close of the 9th century began to settle in Iceland, they carried

with them from the mother country not only their old religion hut

also a store of songs and traditions about the gods and heroes. This

poetry was preserved faithfully by oral transmission, from generation

to generation. Poetical activity soon evinced itself among the

Icelanders themselves, and gradually a great and rich literature

developed, which became far more important and more truly presented

original and national ideas than that of the rest of the Scandinavian

country, whose intellectual productions took on through Christianity

a foreign, learned-Latin stamp. We can, therefore, expect to find

among the Icelanders fuller information about the old faith than

elsewhere, and such is also the case. In the Norwegian Old Icelandic

poetry the Norse religion is worked together into a whole, which

comprises the creation of the world, the relation of gods to men in

life and death, and finally the downfall of the gods and of the world

at Ragnarok, after which there shall come a new heaven and a new

earth where men are judged after their uprightness and good conduct,

and not for their bravery alone.

Odin.

Chief God. — An essential point which we ought to note here is,

as touched upon before, that Odin in this poetry is conceived of

as the chief god, before whom the others, both gods and

goddesses, must bow.

If

we now, in what follows, wish to make a coherent presentation of the

religion as we find it in Norwegian-Icelandic literature, we must in

the first place remember well that Denmark and Sweden hardly had the

same faith, viewed as a whole, even if there are points of conformity

in essentials. It appears among other things from the myths of the

gods which Saxo has presented to us in the first' books of his Latin

history of Denmark, that various details in the teachings about the

gods are told otherwise here (in Denmark) than in Iceland, and that

we have traditions to which nothing in Iceland corresponds and vice

versa. But in the next place the contention is made, especially by

the Norwegian philologist Bogge, that a great many things in

mythological poetry, through contact with the Celts and others in the

Viking expeditions, have been strongly influenced by Christianity,

yes, even by Jewish and Græco-Roman ideas. Against this view,

however, many and important objections are raised; but no one can

deny that Christianity can and must have had in any case some

influence upon the later development of Norse mythology. Finally, it

cannot be strongly enough emphasized that most of the myths and

hero-sagas which are retold in what follows must not be understood as direct

testimony concerning our fathers' belief, but

generally

are only a poetically interpreted and modified portrayal, the

material for which is most certainly derived from the belief of the

people.

Fig. 10 – Altar from

the Iron Age.

Therefore

it is Norwegian-Icelandic mythology such as developed in Viking times

and soon afterwards (800-1100) which we know best, and it is

all we know connectedly. We must see first, then, from what

sources we derive this knowledge.

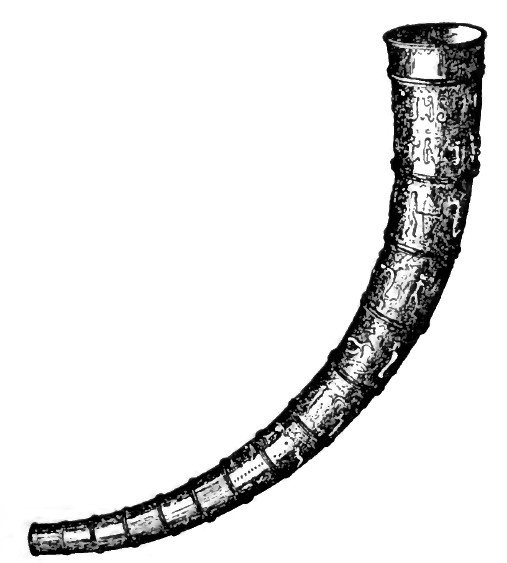

Fig

11. – A Gold Horn.

6. Eddic

Poems and Scaldic Lays. — The oldest and most

important sources are the old Norwegian-Icelandic poems. It is

customary to distinguish between the so-called Eddic Poems and the

Scaldic Lays.

The Eddic

Poems preserved in an Icelandic manuscript and

wrongly

called the Elder Edda were composed in the aforementioned period, in

the time of transition and of conflict between paganism and

Christianity. They are of unknown authorship and treat partly

doctrines of the gods and the heathen view of life in connected form,

and partly the different sagas of gods and heroes which in the North

are usually given a mythological background. The most important of

the Eddic poems will be mentioned in the following pages.

The Scaldic

Lays come from authors whose names are mentioned.

The

oldest and best are from the same period as the Eddic Poems, but only

a few of them have a thoroughly mythological content — chiefly the

"shield poems," treating the myths which arc pictorially

represented on the fields of the shields, and the "Song of

Praise" to the chieftain whose lineage is traced up to the gods.

On the other hand they all contain in their poetic paraphrases, the

so-called Kenningar, allusions to mythology or legendary

history which presupposes that the myth or saga in question is known

to the hearer. When the gallows can be called by a poet "the

cool, windy steed of Signy's bridegroom," the hearer must in

order to understand the expression know well the legend of Hagbarth

and Signy and Hagharth's death on the gallows.

From

Iceland came likewise two important primary sources of Norse

mythology in prose, namely Snorri's Edda and the Saga of the

Volsungs.

Snorri

(d. 1241). — Snorri Sturlason was Iceland's most important

prose author and withal a clever Scald. In his historical

masterpiece, "Heimskringla," he used especially for matters

concerning the earliest time, old Scaldic lays as proofs for his

description, and therefore he acquired accurate and intimate

knowledge of their content: and as a Scald he of necessity completely

understood the substance and nature of the poetical paraphrases. He

then conceived the plan of committing his knowledge to writing, and

therefore he composed his Edda. This word is most closely defined as

"Poetics" or "Handbook for Scalds." The book

falls into three main divisions. The first, Gylfaginning,

'Delusion of Gylfi,' relates the story of a king Gylfi, who journeyed

forth to learn about the power of the Aesir. He disguised himself as

a wayfarer and came to a great hall in which were many people and

three chieftains, who sat each in his high seat, one higher than the

other. These he questioned about all the mythological relations, and

he received clear answers to all his inquiries. Within this framework

Snorri takes occasion to present a general view of the whole doctrine

of the gods, particularly following old poems which he frequently

cites in evidence. He mentions several of the Eddic poems still

preserved, but also some which we do not know now from any other

source.

Fig. 12 – Pictures on

Gold Horns.

Fig.

13 – Pictures on Gold Horns.

Fig.

14 – Laeborg Stone with Sign of Hammer.

The

second section, Skaldskaparmal,4 reviews and

explains the different poetic paraphrases. Where these allude to the

doctrine of the gods or to traditional history, the myths or

traditions in question are recounted and a number of scaldic verses

are cited as passages in evidence.

The

third section, finally, Hattatal,5 which is the

least important for the mythology, is a practical application of the

foregoing theory, since Snorri has composed a number of verses in

different meters, making use of the paraphrases which he has

explained in what preceded.

In

the introduction to the whole and in the arrangement of the material

one easily feels that Snorri has sought to bring about coherence in

the old traditions — perhaps involuntarily under influence of his

Christian faith — and tries to coin history out of myths and sagas,

since Odin is made into a prince versed in magic, dwelling originally

in Asia, but who later wandered to the North, where he became the

ancestor of the kings of the realm and was worshiped as a god. Snorri

advances the same view also in the first part of the Heimskringla,

the so-called Ynglinga Saga, which contains important but obscure

mythological information. 6

The

Saga of the Volsungs contains a connected prose version of the Sagas

of the Volsungs and Nibelung, an amplified re-narration of the Eddic

Hero-Poems; but here, as in Gylfaginning, it is apparent that

the unknown author had for his authority poems now lost.

But

in the other pieces of Icelandic prose literature also there are

given here and there important details about the heathen worship of

the gods and its forms. This applies both to the Heimskringla

(the attempt of the two Olafs to introduce Christianity into Norway)

and to not a few of the family-sagas. There are also found

mythical-heroic sagas in the style of the Volsunga Saga and romantic

sagas with mythological material.

8. Popular

Songs and Saxo. — In the German saga-poetry

Dietrich von Bern (Theodoric of Verona) plays the leading part,

and tales about him have also wandered to the North, where they are

treated both in Eddic poetry and in folk-songs. Meanwhile the same

theme is treated far more explicitly in the Thithrek Saga, which was

composed in Norway in the middle of the 13th century on the basis of

tales and songs of Low German merchants.

Folk-Songs.

— Finally, an important but late source is found in the ancient

ballads proper, which partly contain allusions to myths ("Tor of

Haysgaard," "The Youth Svendal," "Sven Vonved,"

"Rage and Else"), and partly treat whole saga-cycles ("The

Volsungs," "Hagbarth and Signe"). In several of the

magic songs also there are preserved many heathen ideas, while their

apparent Christian character is somewhat superficial. Here we can

also mention popular traditions and popular adventures and

especially popular usages, which have often preserved one or

another heathen reminiscence.

As

already remarked above, Saxo in his ancient history, the first nine

books of his works, retells and works in together a number of sagas

about the gods, heroes, and kings. In his work, which was finished in

the beginning of the 13th century, he has made use of both Danish and

Icelandic 'tradition for its foundation. The ancient history has

extraordinary mythological importance, but as a source it must be

used with the greatest caution. Saxo gives the same historical

interpretation to the whole that he does to any part and therefore he

has altered and rearranged myths and sagas when coherence seemed to

demand it. The old gods are interpreted as might be expected from a

religious author. Old songs are often quoted, but unfortunately in a

remodeled Latin version.

NOTE.

— Canon Adam of Bremen, who lived contemporaneously with Svend

Estridson, made a Latin account of the history of the Archbishop of

Hamburg, in which he also tells of the paganism of the Northern

countries. Of foreign sources which can throw light upon the

interrelation of myths among the Gothic-Germanic people can he named

the "History of the Goths," written by Jordanes, and the

"History of the Lombards," by Paulus Diaconus. Finally,

there are found important contributions on this point. in Old German

and Anglo-Saxon poetry, which is now purely heathen, now Christian

with a background of heathen ideas and expressions. In England are

found not a few pictorial representations with half-heathen content,

of which several will be used in what follows.

_______________________________________

1

In a single instance undoubted images of gods were found in certain

marsh-lands.

2

R answers to voiced S in older stages of the language.

3

Some younger stones from Bornholm and a single one from Skaane need

not be mentioned here.

4

Poetic Phraseology or Language of Poetry.

5

Enumeration or Tale of Meters.

6

"The Round World," History of the Scandinavian Races.

|