| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

SEVEN

A PASSING GLIMPSE OF MANY WINDOWS Short and narrow

Downing Street is the real centre of the British Empire, for the building

numbered 20, looking very much like a cheap lodging house, has been the home of

the Premier of England these two hundred years, since Robert Walpole was Prime

Minister. Burial in

Westminster Abbey is the highest mark of recognition and honour that can be

bestowed by the English nation. In this grand old church have been crowned all

the sovereigns of England from the time of Saxon Harold. Where the Abbey stands

to-day there was once a church commenced by Sebert, King of Essex, in the year

610. It was on Thorney Island, the boundaries of which are not now traceable,

for closely cemented partly by nature partly by artifice, it has become a solid

part of the British Isles. The original church was later destroyed by the

Danes. Another quite as large as the present one was begun in 1050 in the reign

of Edward the Confessor and parts of this old edifice can be traced to-day. In

1220, Henry III. began the rebuilding of the Confessor's church but it was

almost destroyed by fire before its completion. The damage was repaired by

Edward I., and the church was added to by Edward II., Edward III., Henry VII.,

and indeed by all other sovereigns down to the year 1714, when Sir Christopher

Wren undertook its complete restoration, adding the western towers as they are

now. Perhaps no other spot in all the world is so truly holy ground and the

number of the great ones of the earth sleeping here is very large. Under the north

walls of Westminster Abbey is the church of St. Margaret built during the reign

of Edward I. on the site of an earlier church. William Caxton was buried in St.

Margaret's in 1491. The fact that there was a chapel in the old Almonry where

his printing press had stood led to the union branches of the printing trades

being called "Chapels" even to this day. Sir Walter Raleigh is also

buried here. The interest of St. Margaret's centres in a stained glass window

made in Holland for Henry VII., setting forth the Crucifixion, which many times

narrowly escaped destruction and was finally in 1758 purchased by the

churchwardens and given its present resting place. INTERIOR OF ST. MARGARET'S, WESTMINSTER The open space

between Westminster Abbey and Westminster Hospital is the Broad Sanctuary so

called because here in the 15th and 16th centuries was a sacred place of refuge

for criminals who took advantage of the ancient protection of the Church. The

Sanctuary was a square Norman tower containing two chapels. Elizabeth

Woodville, widow of Edward IV., was seeking refuge here when her two children

were taken from her and afterwards killed in the Tower by order of the Duke of

Gloucester. Westminster Hall,

now connected with the Houses of Parliament, was begun in 1097 by William

Rufus, the Conquerer's son, and it was the scene of the first English

parliaments. Richard II. enlarged the building and was here himself deposed.

English kings up to the time of George IV. held their coronation festivals

here. Charles I. was condemned to death in this Hall, and a tablet set in the

floor marks the spot where he listened to his sentence of death. Cromwell was

here hailed as Lord Protector, and here a few years later his head was exposed

for the satisfaction of his enemies. Guy Fawkes of Gunpowder Plot fame, William

Wallace, Sir Thomas More, Somerset, Essex, Strafford and a host of other folk,

were tried and sentenced to death in Westminster Hall. It was in this old Hall,

in our own days, that the body of King Edward VII. lay in state. Between the Houses

of Parliament and Westminster Abbey is an open space called Old Palace Yard,

where in 1618 Sir Walter Raleigh was executed, and where the conspirators of

the Gunpowder Plot met death opposite the very house through which they carried

the powder into cellars under the House of Lords. In Smith Square

just beyond Westminster Abbey is the church of St. John the Evangelist with its

four queer looking towers, one at each corner. It has been here since 1721. The

story is told that it was ordered built by a lady of wealth who objected to the

plans originally drawn, and, angry with the architect when he explained them to

her, she kicked over a footstool. As it lay upside down she pointed to it and

cried out—"Build it like that." The architect followed her

instructions to the letter, hence the odd appearing towers. Church Street

extending eastward from Smith Square towards the river is identified with two

of the books of Dickens. On the south side midway of the block lived Jenny

Wren, the dolls' dressmaker of "Our Mutual Friend," whose back was

bad and whose legs were queer; and down this street, Martha, in "David

Copperfield," fled to the river bent on suicide, with Peggoty and

Copperfield close at her heels. What is now St.

James's Park was once a marshy tract connected with the leper hospital afterwards

St. James's Palace. It remained uncultivated until enclosed by Henry VIII., but

was not actually laid out as a park until the time of Charles II. It was this

king who had the Mall for the palle malle game removed from beside St. James's

Palace to the long straight walk that marks the northern boundary of the park.

Here the fashionable game continued to be played by the cavaliers of the court.

For many a year, the Mall was the most fashionable and exclusive of London's

promenades, and it was along it that Charles I. walked to his execution in

1648. Beau Brummell spent much time on the Mall, whether he went to show to

admiring friends the latest fashions in clothes at the court of his friend and

patron the Prince of Wales afterward George IV. Birdcage Walk by

St. James's Park takes its name from an aviary which has been here from the

time of James I. A continuous line of cages lined the walk when Charles II. was

king, and the "Keeper of the King's Birds" was an important official.

In York Street to

the south of Birdcage Walk, where the Queen Anne Mansions are today was the

house to which Milton removed in 1651. The street was called Petty France then,

from the number of French Protestants residing there. In this house Milton

became blind. Here his wife died leaving three daughters, and later while still

living here Milton married Catherine Woodcock in 1656. A century and a half

later Hazlitt came here to live and set up a stone on the house-side:

Sacred to Milton

Prince of Poets In the wainscoted

room where Milton had often pursued his meditations Hazlitt visited with

Charles and Mary Lamb, Hayden and a host of others. York Street was finally

named in honour of the son of George III., Frederick, Duke of York. In St. James's

Park, where Buckingham Palace stands to-day, Buckingham House was built in 1703

by order of John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham. Later it was given to Queen

Charlotte by George III. to replace Somerset House as a royal residence.

Remodelled in 1825 it became the present Buckingham Palace, the town residence

of the King. The eastern façade facing St. James's Park was added in 1846. Separating the

private grounds of Buckingham Palace from Green Park is Constitution Hill, and

in this road leading from the Palace to Hyde Park Corner attempts were made to

assassinate Queen Victoria in the years 1840, 1842 and 1849 by lunatics of

various degrees. The first building

to the east of Hyde Park Corner is Apsley House, built in 1785, presented to

the Duke of Wellington by the Government; where he dined the survivors of the

Battle of Waterloo every year until his death. The much famed Elgin Marbles now in the British Museum when first brought to London in 1803 from the Acropolis at Athens were placed in Gloucester House in Piccadilly opposite Green Park. Lord Byron spoke irreverently of these relics and their home, calling it the:

General mart

For all the mutilated blocks of art. Aristocratic Park

Lane in early days was a narrow path called Tyburn Lane leading to Tyburn, the

place of execution. It is still a narrow way, but to-day lined with splendid

houses and crowded with the carriages of rich and fashionable Londoners. Out of Park Lane

leads Hertford Street, full of memories of persons of note who have lived

there. A tablet on the house at No. 14 indicates that it has been the home of

Dr. Jenner, the discoverer of vaccination. Other dwellers in the street were

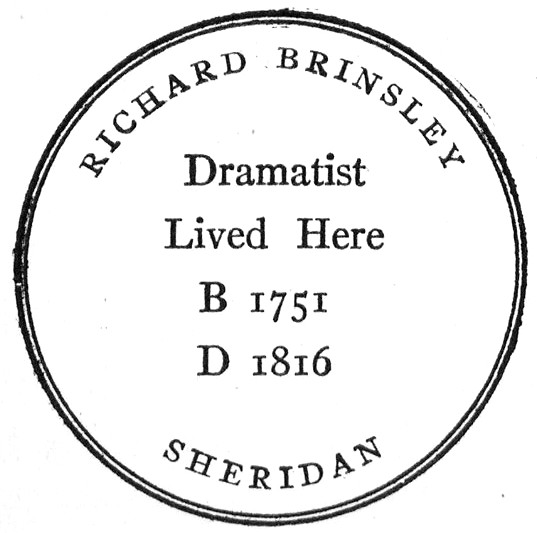

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, dramatist and politician, who lived several years at

No. 10, and Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, novelist, whose house was No. 36. Where Edgware Road

now ends at Marble Arch was once an open space taking its name from the Tyburn

brook which flowed from the north to the Thames River. This was a place of

execution and malefactors of all kinds and conditions were here executed until

1783. Among the many thousands who met death at Tyburn were Jack Sheppard;

Fenton, who killed the Duke of Buckingham, and the thief Jonathan Wild who even

on his way to the gallows picked the parson's pocket. Oxford Street was then

called Tyburn Street and was the road that led straight from Newgate to the

gallows of Tyburn. The prisoners were carried in a cart, usually sitting on

their coffins, holding in their hands the nosegay presented to them in

accordance with old custom in the church of St. Sepulchre before starting for

their last ride. In each cart was a minister. Arrived at Tyburn, the cart was

stopped beneath the scaffold until the noose was adjusted, then driven on,

leaving the prisoner hanging. Hogarth's picture of the execution of the

"Idle Apprentice" gives a detailed sketch of the scene and shows the

galleries from which the spectators watched the gruesome sight. The ancient

cemetery of St. George lay near to Hyde Park close by the Marble Arch. There

may still be seen here the Tomb of Laurence Sterne, author of "Tristram

Shandy" and the "Sentimental Journey." Mrs. Radcliffe, writer of

the "Mysteries of Udolpho," is buried in this graveyard, part of

which is now a spot for recreation. Edgware Road starts

northward from the Marble Arch and is the present-day tracing of an old Roman

Road. The grave of the

great actress Sarah Siddons is in St. Mary's Churchyard, much of which is now a

public park in narrow Harrow Road leading from Edgware Road to the west. Close

by is a statue in honour of the memory of this woman of genius. Upper Baker Street

stretches a short distance from Marylebone Road to the entrance of Regent's

Park. It was in this street that Sherlock Holmes had his rooms and the house is

quite easy to find. Marylebone got its

name from a bourne or rivulet running through a little hamlet far outside the

City of London. As the church of this village was dedicated to St. Mary it came

quite naturally to be known as St. Mary-on-the-bourne and this in time was

shortened to Marylebone. In Marylebone Road

at the end of High Street is Old Mary-le-bone Church where George Gordon, Lord

Byron, was baptised in 1788. Although the older church on this site which

figures often in Hogarth's series of paintings of "The Rake's

Progress," is gone, in the churchyard there is still the flat tombstone on

which the "Idle Apprentice" used to throw dice of a Sunday. At No. 1 Devonshire

Terrace Charles Dickens lived from 1839 to 1851. Here he finished "Barnaby

Rudge" and "Dombey and Son," and wrote "Martin

Chuzzlewit," "Old Curiosity Shop," "David

Copperfield," "The Haunted Man," "The Christmas

Carol," "The Cricket on the Hearth," "American Notes,"

and "The Battle of Life." Here he spent many happy hours with

Carlyle, Longfellow, Hood, Landseer, Macready and a host of other good and

famous men who visited him. A tablet on the

house No. 2 Blandford Street running out of Baker Street to the east, tells

that it was here that Michael Faraday the distinguished chemist served his

apprenticeship. Hertford House in

Manchester Square is the Gaunt House of "Vanity Fair" and it was from

the fourth Marquis of Hertford that Thackeray drew his picture of Lord Steyne.

The building now contains the Wallace Collection of paintings, given to the

nation by Lady Wallace some years ago. During the last

years of his life Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton lived in Grosvenor Square in the

house numbered 12. This is a three-storied structure with a high iron fence,

and before its door pillars on which are flambeaux snuffers attest the age of

the building. These extinguishers were used by the footmen to put out the

flambeaux that were carried lighted on the backs of carriages at night. Writing

of these lights the poet Gay says: Yet who the

footman's arrogance can quell Whose flambeau gilds the sashes of Pall-Mall,

When in long rank a train of torches flame, To light the midnight visits of the

dame. Many men and many

women prominent in the life of London have lived in houses looking upon this

Square during its two hundred years of existence. Mayfair, an

aristocratic residential section of London, has Bond Street and Park Lane on

the east and west; with Piccadilly and Oxford Street on the south and north. It

is named for a fair held where Shepherd's Market is now in each May until about

the middle of the 18th century. Through the Mayfair

district stretches Curzon Street named for the third Viscount Howe—George

Augustus Curzon; noticeable for having no thoroughfare for carriages at either

end. To the west it ends in the cul-de-sac Seamore Place; to the east continued

as Bolton Row it is halted against Devonshire Gardens. In Curzon Street at

No. 8 lived the great friends of Horace Walpole the sisters Mary and Agnes

Berry. Walpole was a constant visitor during the latter years of his life and

it is thought that he strongly desired to marry Mary Berry. Just opposite where

Queen Street ends was the Curzon Street Chapel which was demolished in 1900. It

was in this church that, according to general report, George III. was married

to Hannah Lightfoot in 1759. In the house No. 24 Chantrey the sculptor lived in

an attic during the early years of his struggle for recognition. Thackeray

tells us that Becky Sharp took "a small but elegant house in Curzon

Street," when as Mrs. Crawley she planned to live on nothing a year. Lord

Curzon, former Viceroy of India, is the most notable member of the Curzon , family

to-day. Where Curzon Street

ends Seamore Place juts off at right angles, only a few yards in length. Here

at No. 6 Lady Blessington held her salon in 1830. Chesterfield House,

at the southern end of South Audley Street, was built for the fourth Earl of

Chesterfield who lived and died here. He wrote the famous Chesterfield letters

and their style and eloquence coined the adjective—Chesterfieldian. Jostling side by

side with the homes of the rich, just to the south of Curzon Street, is a

cluster of ancient shattered buildings and dingy shops two hundred and odd

years old. This district is known as Shepherd's Market. Here the fair was held

that gave the name to Mayfair. Many notables have

lived in Clarges Street, named for Sir Walter Clarges, a relative of General

Monk's wife—Anne Clarges. Early in the 19th century No. 11 in this street was

for two years the home of Lady Emma Hamilton, the friend of the greatest of

British Admirals, Lord Nelson. At No. 21 lived the celebrated lady scholar,

Elizabeth Carter, a comrade of Dr. Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds and Edmund

Burke. In this street, too, lived Edmund Kean the actor, and Thomas Babington

Macaulay, equally famous in their different arts. Charles Street has

changed less in appearance and atmosphere than any other of the Mayfair

streets. It was here, where the house numbered 42 is, that Beau Brummell lived

in 1792. Memories crowd

thickly about the old houses around Berkeley Square, laid out in 1698. On the

west side in the house numbered 45 Lord Clive the founder of the British Empire

in India, lived, and where he killed himself in 1774. At No. 11 Horace Walpole

whose letters give the record of fashionable society of his day died in 1797. Below the level of

the Lansdowne Gardens, off Berkeley Street, is the Lansdowne Passage. The

curious iron bar that blocks the entrance is a reminder of the act of a bold

highwayman in the last days of the 18th century. After robbing a man in nearby

Piccadilly, and mounting his horse, he dashed through Bolton Street, then through

this passage and up the stone steps at full gallop. The bars were put up to

prevent a recurrence of this. Anthony Trollope in his book "Phineas

Redux" makes this dark uncanny looking passage the scene of a murder, and

the place where a body was found. Opposite Lansdowne

Passage is Hay Hill, once a favourite resort of highwaymen. Here the Prince of

Wales, afterwards George IV., and the Duke of York were halted one night by a

man, revolver in hand, who fared ill, however, as the two nobleman had only three

shillings between them. It was a custom to exhibit on Hay Hill the heads of

executed persons as an example to evildoers. Here was exposed the head of

Thomas Wyatt the younger, in the rebellion of 1554 when he was captured after

his attack on Ludgate Hill. In Berkeley Street

a few doors south of Berkeley Square lived Alexander Pope, the poet, on the

east side of the street opposite Lansdowne House. Dover Street, named

for a very early resident, Henry Jermyn, Lord Dover, was long a thoroughfare

noted for the homes of statesmen. John Evelyn, the diarist, lived here, near

Piccadilly, and in 1705 died here. To-day it is wholly given over to trade. Albemarle Street

was a dignified thoroughfare, and here lived at different times James and

Robert Adam, two of the famous brothers who laid out the Adelphi district;

Zoffany, who painted the portrait of John Wilkes; Lord Butte, and Charles and

James Fox. Now it is as much of a business section as it was once residential. In quiet Savile Row

the place of high-priced tailors, on No. 12, a yellow brick house with link

snuffers before the door, is a tablet telling that here Grote the historian

died, and reading: George Grote

1794-1871 Historian Died Here Close by in Savile

Row No. 14 is a house now quite conventional in appearance where Sheridan the

dramatist lived and died, as is set forth on the tablet of the house-front:  Shunned by his

friends Sheridan was arrested for debt on his deathbed and but for his

physician who declared that his removal would be fatal would have been moved

away. In contrast to his lonely deathbed, his burial in Westminster Abbey was

attended by a great concourse of people of the highest rank who gathered to do

homage to the genius of the man whom living they forgot. Queer Albany

Courtyard lies close by Sackville Street and is entered from bustling

Piccadilly, passing from a thoroughfare of busy shops to a courtyard of

asphalt, quiet and dignified. After a few yards the space widens and a moderate

sized square brick building looms up. This is the "Albany," with no

external suggestion of the many memories within. Byron lived here, and Lord

Lytton, Monk Lewis, Canning and other great folk. In St. James's

Church in Piccadilly almost opposite the "Albany," is buried the

eccentric Duke of Queensberry, better known as "Old Q," and Charles

Cotton, the friend of Izaak Walton, fisherman. A tablet on the outer wall

reads: Tom D'Urfey

Dyed February 26 1723 This was the poet

who wrote "Pills to Purge' Melancholy," and whose name crept into

history more because of his friendship for Charles II. and of the king's for

him than for the actual merit of his verse. Addison wrote of him: "Many an

honest gentleman has got a reputation in his country, by pretending to have

been in company with Tom D'Urfey." Lord Chesterfield, the letter writer,

was baptised here. St. James's Street

off Piccadilly and terminating at the gateway of St. James's Palace is the

street in which Lord Byron lived, at No. 8, when the world acclaimed him a

poet. Of St. James's Street Frederick Locker Lampson wrote: Why that's where

Sacharissa sigh'd

When Waller read his ditty; Where Byron lived and Gibbon died And Alvanley was witty. Sir Christopher Wren died at his

home in this street in 1723. Close by the Pall Mall end the Conservative Club

stands on the site of the house where Gibbon, the historian of the Roman

Empire, died in 1794. Next door to Gibbon's home, set well back from the

street, stood the Thatched House Tavern, for two centuries a meeting place for

littérateurs, and such famous clubs as the Dilettanti and the Literary. The

Brothers Club, of which Dean Swift was one of the organisers, also met in the

Thatched House Tavern and concerning this club Swift wrote to Stella: "The

end of our Club is to advance conversation and friendship, and to reward

learning without interest or recommendation. We take in none but men of wit, or

men of interest; and if we go on as we began, no other Club in this town will

be worth talking of." But the time came before long when he wrote again to

Stella that there was much drinking and little thinking at the Brothers and

that the business the members met to consider was usually deferred to a more convenient

season. In one of the shops beneath the wall of this tavern was the

hair-dressing establishment of the great Rowland who made a fortune with his

Macassar Oil—a fortune doubtless largely contributed to by his regular

business, since he charged five shillings for cutting hair. St. James's Street

ends at the gateway to St. James's Palace. This gateway designed by Holbein is

one of the few survivals of the original palace where in the open fields was

once a hospital for lepers founded in 1190. The royal palace took the place of

the hospital buildings under Henry VIII., who had Holbein design the structure.

It was a royal abode until the time of George IV. Here Queen Mary died; here

Charles I. slept the night before he walked through St. James's Park to

Whitehall and to death, and here Charles II. and James II. were born. This,

too, was the refuge for Marie de Medici in some of her unhappy wanderings. In Bury Street

beyond St. James's Street, Steele lived after his marriage. Horace Walpole also

had lodgings here and so had Crabbe and Tom Moore. Dean Swift lived in this

thoroughfare for a time, and it was from his Bury Street quarters that he wrote

to the unfortunate Stella: "I have the first floor, a dining room, and a

bed chamber, at eight shillings a week, plaguy dear." Willis's restaurant

in King Street stands on the site of Almack's the famous club opened in 1765,

of which strange stories have been recounted. It is told that when a man

dropped ill before the door and was carried inside club members made bets on

his chances of life or death. When a doctor arrived his ministrations were

interfered with because the members said that any medical aid would affect the

fairness of the bets. So this must have been a great gaming place indeed. Pall Mall now the

thoroughfare of fashionable clubs got its name from the Italian game of palle-malle played with a palla and

maglia—otherwise ball and mallet—which Charles I. introduced into England about

1635. Pall Mall was a suburban promenade until 1689 when it was laid out as it

is to-day. At first it was called Catherine Street in honour of Catherine of

Braganza Queen of Charles II. Nell Gwynne lived in this street from 1671 until

her death in 1687 where No. 79 now is, and it was over the wall of the surrounding

garden that she used to talk with Charles II. Here gas was first experimented

with as a street illuminative, when in 1807 a row of lamps were set up before

the colonnade of Carlton House. The Smyrna Coffee

House celebrated in the days of Queen Anne for the group of writers who

gathered here to talk politics in the evenings was in Pall Mall close to

Waterloo Place on the south side. Prior and Swift came here much together.

Thomson the poet was a regular visitor and put up a notice announcing that subscriptions

would be taken by the author for "The Four Seasons." St. James's Square

is a reminder of the times of Charles II. who had it laid out. In a house on

the east side, now London House, Lord Chesterfield was born in 1694. Next door

at the southeast corner now part of Norfolk House, is where George III. was

born in 1738. It was around this square that Savage and Johnson brimful of much

patriotism but having little money used to walk together. Where now stands

the York Column in Waterloo Place leading to Waterloo Steps and The Mall was

the main entrance to Carlton House, built for Henry Boyle, Lord Carlton, in

1709, and afterwards occupied by the Prince Regent who became George IV. When

the old building was demolished in 1827 the columns of the entrance were saved

and used in 1832 to form the façade of the National Gallery in Trafalgar

Square. The name of the

Haymarket has clung to it since the reign of Elizabeth when it was a mart for

the sale of hay and straw and which existed until 1829. The short and

crooked street called Suffolk, off Pall Mall East, began its existence in the

middle of the 17th century and marks the site of one of the homes of the Earl

of Suffolk. It was in this street that Esther Vanhomrige lived for several

years—Vanessa, the story of whose life is inseparable from that of Dean Swift.

It was here also that Moll Davis lived in a house fitted up for her by King

Charles II. |