|

XV A LUCKY STROKE "Mr. Munchausen," said Ananias, as

he and the famous warrior drove off from the first hole at the Missing Links,

"you never seem to weary of the game of golf. What is its precise charm in

your eyes, — the health-giving

qualities of the game or its capacity for bad lies?" "I owe my life to

it," replied the Baron. "That is to say to my precision as a player I

owe one of the many preservations of my existence which have passed into

history. Furthermore it is ever varying in its interest. Like life itself it is

full of hazards and no man knows at the beginning of his stroke what will be

the requirements of the next. I never told you of the bovine lie I got once

while playing a match with Bonaparte, did I?" "I do not recall

it," said Ananias, foozling his second stroke into the stone wall. "I was playing with my

friend Bonaparte, for the Cosmopolitan Championship," said Munchausen,

"and we were all even at the thirty-sixth hole. Bonaparte had sliced his

ball into a stubble field from the tee, whereat he was inclined to swear, until

by an odd mischance I drove mine into the throat of a bull that was pasturing

on the fair green two hundred and ninety-eight yards distant. 'Shall we take it

over?' I asked. 'No,' laughed Bonaparte, thinking he had me. 'We must play the

game. I shall play my lie. You must play yours.' 'Very well,' said I. 'So be

it. Golf is golf, bull or no bull.' And off we went. It took Bonaparte seven

strokes to get on the green again, which left me a like number to extricate my

ball from the throat of the unwelcome bovine. It was a difficult business, but

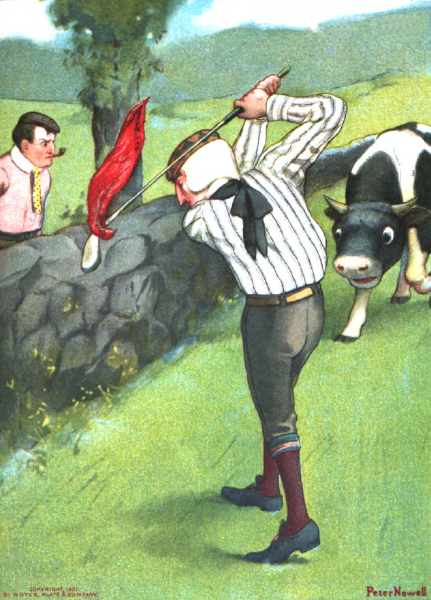

I made short work of it. Tying my red silk handkerchief to the end of my brassey

I stepped in front of the great creature and addressing an imaginary ball

before him made the usual swing back and through stroke. The bull, angered by

the fluttering red handkerchief, reared up and made a dash at me. I ran in the

direction of the hole, the bull in pursuit for two hundred yards. Here I hid

behind a tree while Mr. Bull stopped short and snorted again. Still there was

no sign of the ball, and after my pursuer had quieted a little I emerged from

my hiding place and with the same club and in the same manner played three. The

bull surprised at my temerity threw his head back with an angry toss and tried

to bellow forth his wrath, as I had designed he should, but the obstruction in

his throat prevented him. The ball had stuck in his pharynx. Nothing came of his

spasm but a short hacking cough and a wheeze

— then silence. 'I'll play four,' I cried to Bonaparte, who stood watching

me from a place of safety on the other side of the stone wall. Again I swung my

red-flagged brassey in front of the angry creature's face and what I had hoped

for followed. The second attempt at a bellow again resulted in a hacking cough

and a sneeze, and lo the ball flew out of his throat and landed dead to the hole.

The caddies drove the bull away. Bonaparte played eight, missed a putt for a

nine, stymied himself in a ten, holed out in twelve and I went down in

five." "Jerusalem!"

cried Ananias. "What did Bonaparte say?"  "Again I swung my red-flagged brassey in front of the angry creature's face, and what I had hoped for followed." "He delivered a short,

quick nervous address in Corsican and retired to the club-house where he spent

the afternoon drowning his sorrows in Absinthe high-balls. 'Great hole that,

Bonaparte,' said I when his geniality was about to return. 'Yes,' said he. 'A

regular lu-lu, eh?' said I. 'More than that, Baron,' said he. 'It was a

Waterlooloo.' It was the first pun I ever heard the Emperor make." "We all have our weak

moments," said Ananias drily, playing nine from behind the wall. "I

give the hole up," he added angrily. "Let's play it out

anyhow," said Munchausen, playing three to the green. "All right,"

Ananias agreed, taking a ten and rimming the cup. Munchausen took three to go

down, scoring six in all. "Two up," said

he, as Ananias putted out in eleven. "How the deuce do you

make that out? This is only the first hole," cried Ananias with some show

of heat. "You gave up a hole,

didn't you?" demanded Munchausen. "Yes." "And I won a hole,

didn't I?" "You did — but — " "Well that's two

holes. Fore!" cried Munchausen. The two walked along in

silence for a few minutes, and the Baron resumed. "Yes, golf is a

splendid game and I love it, though I don't think I'd ever let a good

canvasback duck get cold while I was talking about it. When I have a canvasback

duck before me I don't think of anything else while it's there. But

unquestionably I'm fond of golf, and I have a very good reason to be. It has

done a great deal for me, and as I have already told you, once it really saved

my life." "Saved your life,

eh?" said Ananias. "That's what I

said," returned Mr. Munchausen, "and so of course that is the way it

was." "I should admire to

hear the details," said Ananias. "I presume you were going into a

decline and it restored your strength and vitality." "No," said Mr.

Munchausen, "it wasn't that way at all. It saved my life when I was

attacked by a fierce and ravenously hungry lion. If I hadn't known how to play

golf it would have been farewell forever to Mr. Munchausen, and Mr. Lion would

have had a fine luncheon that day, at which I should have been the turkey and

cranberry sauce and mince pie all rolled into one." Ananias laughed. "It's easy enough to

laugh at my peril now," said Mr. Munchausen, "but if you'd been with

me you wouldn't have laughed very much. On the contrary, Ananias, you'd have

ruined what little voice you ever had screeching." "I wasn't laughing at

the danger you were in," said Ananias. "I don't see anything funny in

that. What I was laughing at was the idea of a lion turning up on a golf

course. They don't have lions on any of the golf courses that I am familiar

with." "That may be, my dear

Ananias," said Mr. Munchausen, "but it doesn't prove anything. What

you are familiar with has no especial bearing upon the ordering of the Universe.

They had lions by the hundreds on the particular links I refer to. I laid the

links out myself and I fancy I know what I am talking about. They were in the

desert of Sahara. And I tell you what it is," he added, slapping his knee enthusiastically,

"they were the finest links I ever played on. There wasn't a hole shorter

than three miles and a quarter, which gives you plenty of elbow room, and the

fair green had all the qualities of a first class billiard table, so that your

ball got a magnificent roll on it." "What did you do for

hazards?" asked Ananias. "Oh we had 'em by the

dozen," replied Mr. Munchausen. "There weren't any ponds or stone

walls, of course, but there were plenty of others that were quite as

interesting. There was the Sphynx for instance; and for bunkers the pyramids

can't be beaten. Then occasionally right in the middle of a game a caravan ten

or twelve miles long, would begin to drag its interminable length across the

middle of the course, and it takes mighty nice work with the lofting iron to

lift a ball over a caravan without hitting a camel or killing an Arab, I can

tell you. Then finally I'm sure I don't know of any more hazardous hazard for a

golf player — or for anybody else for

that matter — than a real hungry African

lion out in search of breakfast, especially when you meet him on the hole

furthest from home and have a stretch of three or four miles between him and

assistance with no revolver or other weapon at hand. That's hazard enough for

me and it took the best work I could do with my brassey to get around it." "You always were

strong at a brassey lie," said Ananias. "Thank you," said

Mr. Munchausen. "There are few lies I can't get around. But on this

morning I was playing for the Mid-African Championship. I'd been getting along

splendidly. My record for fifteen holes was about seven hundred and

eighty-three strokes, and I was flattering myself that I was about to turn in

the best card that had ever been seen in a medal play contest in all Africa. My

drive from the sixteenth tee was a simple beauty. I thought the ball would

never stop, I hit it such a tremendous whack. It had a flight of three hundred

and eighty-two yards and a roll of one hundred and twenty more, and when it

finally stopped it turned up in a mighty good lie on a natural tee, which the

wind had swirled up. Calling to the monkey who acted as my caddy — we used monkeys for caddies always in

Africa, and they were a great success because they don't talk and they use their

tails as a sort of extra hand, — I

got out my brassey for the second stroke, took my stance on the hardened sand,

swung my club back, fixed my eye on the ball and was just about to carry

through, when I heard a sound which sent my heart into my boots, my caddy galloping

back to the club house, and set my teeth chattering like a pair of castanets.

It was unmistakable, that sound. When a hungry lion roars you know precisely

what it is the moment you hear it, especially if you have heard it before. It

doesn't sound a bit like the miauing of a cat; nor is it suggestive of the

rumble of artillery in an adjacent street. There is no mistaking it for distant

thunder, as some writers would have you believe. It has none of the gently

mournful quality that characterises the soughing of the wind through the leafless

branches of the autumnal forest, to which a poet might liken it; it is just a

plain lion-roaring and nothing else, and when you hear it you know it. The man

who mistakes it for distant thunder might just as well be struck by lightning

there and then for all the chance he has to get away from it ultimately. The

poet who confounds it with the gentle soughing breeze never lives to tell about

it. He gets himself eaten up for his foolishness. It doesn't require a Daniel

come to judgment to recognise a lion's roar on sight. "I should have

perished myself that morning if I had not known on the instant just what were

the causes of the disturbance. My nerve did not desert me, however, frightened

as I was. I stopped my play and looked out over the sand in the direction

whence the roaring came, and there he stood a perfect picture of majesty, and a

giant among lions, eyeing me critically as much as to say, 'Well this is luck,

here's breakfast fit for a king!' but he reckoned without his host. I was in no

mood to be served up to stop his ravening appetite and I made up my mind at once

to stay and fight. I'm a good runner, Ananias, but I cannot beat a lion in a

three mile sprint on a sandy soil, so fight it was. The question was how. My

caddy gone, the only weapons I had with me were my brassey and that one little

gutta percha ball, but thanks to my golf they were sufficient. "Carefully calculating

the distance at which the huge beast stood, I addressed the ball with unusual

care, aiming slightly to the left to overcome my tendency to slice, and drove

the ball straight through the lion's heart as he poised himself on his hind

legs ready to spring upon me. It was a superb stroke and not an instant too

soon, for just as the ball struck him he sprang forward, and even as it was

landed but two feet away from where I stood, but, I am happy to say, dead. "It was indeed a

narrow escape, and it tried my nerves to the full, but I extracted the ball and

resumed my play in a short while, adding the lucky stroke to my score meanwhile.

But I lost the match, — not because I

lost my nerve, for this I did not do, but because I lifted from the lion's

heart. The committee disqualified me because I did not play from my lie and the

cup went to my competitor. However, I was satisfied to have escaped with my

life. I'd rather be a live runner-up than a dead champion any day." "A wonderful

experience," said Ananias. "Perfectly wonderful. I never heard of a

stroke to equal that." "You are too modest,

Ananias," said Mr. Munchausen drily. "Too modest by half. You and

Sapphira hold the record for that, you know." "I have forgotten the

episode," said Ananias. "Didn't you and she

make your last hole on a single stroke?" demanded Munchausen with an

inward chuckle. "Oh — yes," said Ananias grimly, as he

recalled the incident. "But you know we didn't win any more than you

did." "Oh, didn't you?"

asked Munchausen. "No," replied

Ananias. "You forget that Sapphira and I were two down at the

finish." And Mr. Munchausen played

the rest of the game in silence. Ananias had at last got the best of him. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2015

(Return to Web Text-ures)