THE SLEEPING BEAUTY

There

were once a King and Queen who had no children, though they had been

married

for many years. At last, however, a little daughter was born to them,

and this

was a matter of great rejoicing through all the kingdom.

When

the time came for the little Princess to be christened, a grand feast

was

prepared, and six powerful fairies were asked to stand as her

godmothers.

Unfortunately the Queen forgot to invite the seventh fairy, who was the

most

powerful of them all, and was also very wicked and malicious.

On

the day of the christening the six good fairies came early, in chariots

drawn

by butterflies, or by doves or wrens or other birds. They were made

welcome by

the King and Queen, and after some talk they were led to the hall where

the

feast had been set out. Everything there was very magnificent. There

were

delicious fruits and meats and pastries and game and everything that

could be

thought of. The dishes were all of gold, and for each fairy there was a

goblet

cut from a single precious stone. One was a diamond, one a sapphire,

one a

ruby, one an emerald, one an amethyst, and one a topaz. The fairies

were

delighted with the beauty of everything. Even in their own fairy

palaces they

had no such goblets as those the King had had made for them.

They

were just about to take their places at the table when a great noise

was heard

outside on the terrace. The Queen looked from the window and almost

fainted at

the sight she saw. The bad fairy had arrived. She had come uninvited,

and the

Queen guessed that it was for no good that she came. Her chariot was of

black

iron, and was drawn by four dragons with flaming eyes and brass scales.

The

fairy sprang from her chariot in haste, and came tapping into the hall

with her

staff in her hand.

“How

is this? How is this?” she cried to the Queen. “Here all my sisters

have been

invited to come and bring their gifts to the Princess, and I alone have

been

forgotten.”

The

Queen did not know what to answer. She was frightened. However, she

tried to

hide her fear, and made the seventh fairy as welcome as the others. A

place was

set for her at the King’s right hand, and he and the Queen tried to

pretend

they had expected her to come. But for her there was no precious

goblet, and

when she saw the ones that had been given to the six other fairies her

face

grew green with envy, and her eyes flashed fire. She ate and drank, but

she

said never a word.

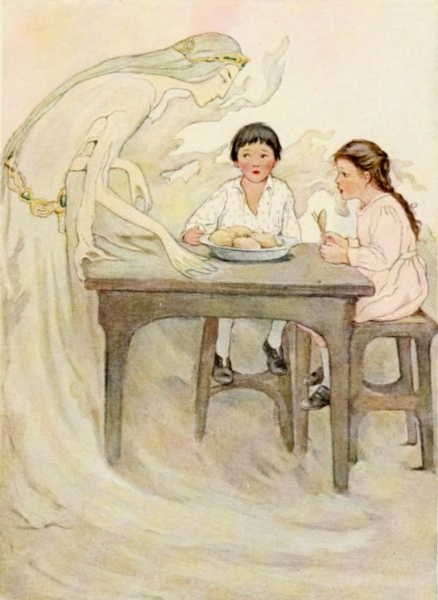

After

the feast the little Princess was brought into the room, and she smiled

so

sweetly and looked so innocent that only a wicked heart could have

planned evil

against her.

The

first fairy took the child in her arms and said, “My gift to the

Princess shall

be that of contentment, for contentment is better than gold.”

“Yet

gold is good,” said the second fairy, “and I will give her the gift of

wealth.”

“Health

shall be hers,” said the third, “for wealth is of little use without

it.”

“And

I,” said the fourth, “will gift her with beauty to win all hearts.”

“And

wit to charm all ears,” said the fifth. “That is my gift to her.”

The

sixth fairy hesitated, and in that moment the wicked one stepped

forward. While

the others had spoken she had been swelling with spite like a toad.

“And I

say,” cried she, “that in her seventeenth year she shall prick her

finger with

a spindle and fall dead.”

When

the Queen heard this she shrieked aloud, and the King grew as pale as

death.

But the sixth fairy stepped forward.

“Wait

a bit,” said she. “I have not spoken yet. I cannot undo what our sister

has

done, but I say that the Princess shall not really die. She shall fall

into a

deep sleep that shall last a hundred years, and all in the castle shall

sleep

with her. At the end of that time she shall be awakened by a kiss.”

When

the wicked fairy heard this she was filled with rage, but she had

already

spoken; she could do no more. She rushed out of the castle and jumped

into her

chariot, and the dragons carried her away, and where she went no one

either

knew nor cared.

The

other fairies also went away, and they were sad because of what was to

happen

to the Princess.

But

at once the King gave orders that every spinning-wheel and spindle in

the land

should be destroyed, and when this was done he felt quite happy again.

For if

all the spindles were gone the Princess could not prick her finger with

one;

and if she did not prick her finger she would not fall into the

enchanted

sleep.

So

the King and Queen were at peace, and all went well in the castle for

seventeen

years. All that the fairies had promised to the Princess came true. She

was so

beautiful that she was the wonder of all who saw her, and so witty and

gentle-hearted that everyone loved her. Beside this she had health,

wealth, and

contentment, and was smiling and joyous from morn till night.

One

day the King and Queen went away on a journey, and the Princess took it

into her

head to mount to a high tower where she had never been before, and to

watch for

their return from there.

She

found the stairs that led to the tower, and then she mounted them, up

and up

and up, until she was high above the roofs of the castle. At last she

reached

the very top of the tower, and there was an iron door with a rusty key

in it.

The Princess

turned the key and the door swung open. Beyond she saw a room, and an

old, old,

wrinkled woman sat there at a wheel spinning.

The

Princess had never seen a spinning-wheel before. It seemed a curious

thing to

her. She went in and stood close to the old woman so as to see it

better.

“What

is that you are doing?” she asked.

“I am

spinning,” answered the old woman.

“And

what is that little thing that flies around so fast?”

“That

is a spindle.”

“It

is a curious little thing,” said the Princess, and she reached out her

hand to

touch it. Then the point of the spindle pricked her finger, and at once

the

Princess sighed, and her eyes closed, and she sank back on a couch in a

deep

sleep.

Immediately

a silence fell also upon all in the castle. The King and Queen had just

returned from their journey; they had alighted from their horses and

had

entered the castle, and just then sleep fell upon them. The courtiers

who

followed them also fell asleep. The dogs and horses in the courtyard

slept, and

the pigeons on the eaves. The boy who turned the spit in the kitchen

slept and

the cook did not scold him, for she too was asleep. The meat did not

burn, for

the fire was sleeping. Even the flies in the castle and the bees among

the

flowers hung motionless. All slept.

Then

all about the castle sprang up an enchanted forest that shut it in like

a wall.

The forest grew so dark and high that at last not even the top-most

tower of

the castle could be seen.

But

though the Princess slept she was not forgotten. Many brave princes and

heroes

came and tried to cut their way through the forest to rescue her, but

the

boughs and branches were as hard as iron, and moreover as fast as they

were cut

away they grew again; also they were twisted so closely together that

no one

could creep between them. Then as years passed by, the brave heroes who

had

sought the Princess grew old and had children of their own. These, too,

grew to

be men and married, and at last the Princess was forgotten by all, or

was

remembered only as an old tale.

At

last a hundred years had slipped away, and then a young and handsome

Prince

came by that way. He had been hunting, and he had ridden so fast and

eagerly

that he had left his huntsmen far behind. Now he was hot and weary, and

seeing

a hut he stopped and asked for a drink of water.

The

man who lived in the hut was very old. He brought the water the Prince

asked

for, and after the Prince had drank, he sat awhile and looked about

him. “What

is that darkness, like a cloud, that I see over yonder?” he asked.

“I

cannot tell you for sure,” said the old man, “for it is a long distance

away

and I have never gone to see. But my grandfather told me once that it

was an

enchanted forest. He said there was a castle hidden deep in the midst

of it,

and that in that castle lay a Princess asleep. That Princess, so he

said, was

the most beautiful Princess in all the world, but a spell had been laid

on her,

and she was to sleep a hundred years. At the end of that time a Prince

was to

come and waken her with a kiss.”

“And

how long has she slept now?” asked the Prince, and his heart beat in

his breast

like a bird.

“That

I cannot say,” answered the old man, “but a long, long time. My

grandfather was

an old man when he told me, and he could not remember her.”

The

Prince thanked the old man for what he had told him, and then he rode

away

toward the enchanted forest, and he could not go fast enough, he was in

such

haste.

When

he was at a distance from the forest, it looked like a dark cloud, but

as he

came nearer it began to grow rosy. All the boughs and briers had begun

to bud.

By the time he was close to them they were in full flower, and when he

reached

the edge of the forest the branches divided, leaving an open path

before him.

Along this path the Prince rode and before long he came to the palace.

He

entered the courtyard and looked about him wondering. The dogs lay

sleeping in

the sunshine and never wakened at his coming. The horses stood like

statues.

The guards slept leaning on their arms.

The

Prince dismounted and went on into the palace; on he went through one

room

after another, and no one woke to stop nor stay him. At last he came to

the

stairway that led to the tower and he went on up it, — up and up, as

the

Princess had done before him. He reached the tower-room, and then he

stopped,

and stood amazed. There on the couch lay a maiden more beautiful than

he had

ever dreamed of. He could scarcely believe there was such beauty in the

world.

He looked and looked and then he stooped and kissed her.

The

Sleeping Beauty

The

Sleeping Beauty

At

once — on the moment — all through the castle sounded the hum of waking

life.

The King and Queen, down in the throne-room stirred and rubbed their

eyes. The

guards started from sleep. The horses stamped, the dogs sprang up

barking. The

meat in the kitchen began to burn, and the cook boxed the boy’s ears.

The

courtiers smiled and bowed and simpered.

Up in

the tower the Princess opened her eyes, and as soon as she saw the

Prince she

loved him. He took her hand and raised her from the couch. “Will you be

my own

dear bride?” said he. And the Princess answered yes.

And

so they were married with great rejoicings, and the six fairies came to

the

wedding and brought with them gifts more beautiful than ever were seen

before.

As for the seventh fairy, if she did not burst with spite she may be

living

still. But the Prince and Princess lived happily forever after.

JACK

AND THE BEAN-STALK

Jack

and his mother lived all alone in a little hut with a garden in front

of it,

and they had nothing else in the world but a cow named Blackey.

One

time Blackey went dry; not a drop of milk would she give. “See there

now!” said

the mother. “If Blackey doesn’t give us milk we can’t afford to keep

her.

You’ll have to take her off to market, Jack, and sell her for what you

can

get.”

Jack

was sorry that the little cow had to be sold, but he put a halter

around her

neck and started off with her.

He

had not gone far, when he met a little old man with a long gray beard.

“Well,

Jack,” said the little old man, “where are you taking Blackey this fine

morning?”

Jack

was surprised that the stranger should know his name, and that of the

cow, too,

but he answered politely, “Oh, I am taking her to market to sell her.”

“There

is no need for you to go as far as that,” said the little old man, “for

I will

buy her from you for a price.”

“What

price would you give me?” asked Jack, for he was a sharp lad.

“Oh,

I will give you a handful of beans for her,” said the old man.

“No,

no,” Jack shook his head. “That would be a fine bargain for you; but it

is not

beans but good silver money that I want for my cow.”

“But

wait till you see the beans,” said the old man; and he drew out a

handful of

them from his pocket. When Jack saw them his eyes sparkled, for they

were such

beans as he had never seen before. They were of all colors, red and

green and

blue and purple and yellow, and they shone as though they had been

polished.

But still Jack shook his head. It was silver pieces his mother wanted,

not

beans.

“Then

I will tell you something further about these beans,” said the man.

“This is

such a bargain as you will never strike again; for these are magic

beans. If

you plant them they will grow right up to the sky in a single night,

and you

can climb up there and look about you if you like.”

When

Jack heard that he changed his mind, for he thought such beans as that

were

worth more than a cow. He put Blackey’s halter in the old man’s hand,

and took

the beans and tied them up in his handkerchief and ran home with them.

His

mother was surprised to see him back from market so soon.

“Well,

and have you sold Blackey?” she asked.

Yes,

Jack had sold her.

“And

what price did you get for her?”

Oh,

he got a good price.

“But

how much? How much? Twenty-five dollars? Or twenty? Or even ten?”

Oh,

Jack had done better than that. He had sold her to an old man down

there at the

turn of the road for a whole handful of magic beans; and then Jack

hastened to

untie his handkerchief and show the beans to his mother.

But

when the widow heard he had sold the cow for beans she was ready to cry

for

anger. She did not care how pretty they were, and as to their being

magic beans

she knew better than to believe that. She gave Jack such a box on the

ears that

his head rang with it, and sent him up to bed without his supper, and

the beans

she threw out of the window.

The

next morning when Jack awoke he did not know what had happened. All of

the room

was dim and shady and green, and there was no sky to be seen from the

window, —

only greenness.

He

slipped from bed and looked out, and then he saw that one of the magic

beans

had taken root in the night and grown and grown until it had grown

right up to

the sky. Jack leaned out of the window and looked up and he could not

see the

top of the vine, but the bean-stalk was stout enough to bear him, so he

stepped

out onto it and began to climb.

He

climbed and he climbed until he was high above the roof-top and high

above the

trees. He climbed till he could hardly see the garden down below, and

the birds

wheeled about him and the wind swayed the bean-stalk. He climbed so

high that

after awhile he came to the sky country, and it was not blue and hollow

as it

looks to us down here below. It was a land of flat green meadows and

trees and

streams, and Jack saw a road before him that led straight across the

meadows to

a great tall gray castle.

Jack

set his feet in the road and began to walk toward the castle.

He

had not gone far when he met a lovely lady, and she was a fairy, though

Jack

did not know it.

“Where

are you going, Jack?” she asked.

“I’m

going to yonder castle to have a look at it,” said Jack.

“That

is well,” said the lady, “only you must be careful how you poke about

there,

for that castle belongs to a very fierce and rich and terrible giant:

and now I

will tell you something: all the riches he has used to belong to your

father;

the giant stole them from him, so if you can fetch anything away with

you it

will be a right and fair thing.”

Jack

thanked her for what she told him, and then he went on, setting one

foot before

the other.

After

awhile he came to the castle, and there was a woman sweeping the steps,

and she

was the giant’s wife.

When

she saw Jack she looked frightened. “What do you want here?” she cried.

“Be off

with you before my husband comes home, for if he finds you here it will

be the

worse for you I can tell you.”

“Yes,

yes, I know”; said Jack, “but I’ve had no breakfast, and I’m like to

drop I’m

so hungry. Just give me a bite to stay my stomach and I’ll be off.” The

giant’s

wife did not want to do that at all, but Jack begged and coaxed until

at last

she let him come into the house and got out a bit of bread and cheese

for him.

Jack

had hardly set down to it when there was a great noise and stamping

outside.

“Oh,

mercy!” cried the giant’s wife, and she turned quite pale. “There’s my

husband

coming in, and if he sees you here he’ll swallow you down in a trice,

and give

me a beating into the bargain.”

When

Jack heard that he did not like it at all. “Can you not hide me some

place?” he

asked.

“Here,

creep into this copper pot,” cried the woman, taking off the lid. She

helped

Jack into the pot and put the lid over him, and she had no more than

done it

before the giant came stumping into the room.

“Fee,

fi, fo, fum!

I

smell the blood of an Englishman!”

he roared.

“Be

he alive or be he dead

I’ll

grind his bones to make my bread.”

“What

nonsense!” said his wife. “If anyone had come here don’t you suppose I

would

have seen him? A crow flew over the roof and dropped a bone down the

chimney,

and that is what you smell.”

When

she said that the giant believed her. He sat down at the table and

called for

breakfast. The woman set before him three whole roasted oxen and two

loaves of

bread each as big as a hogshead, and the giant ate them up in a

twinkling.

“Now,

wife, bring me my moneybags from the treasure-room,” he said.

His wife

went out through a great door studded with nails, and when she came

back she

brought two bags with her and set them on the table in front of the

giant. The

giant untied the strings and opened them, and they were full of

clinking golden

money. The giant sat there and counted and counted the money. After it

was all

counted he put it back in the bags again, and then he stretched his

legs out in

front of him and went to sleep and snored until the rafters shook.

The

giant’s wife worked around for awhile and then she went into another

room. Jack

waited until he was sure she had gone, and then he pushed the lid of

the pot

aside and crept out. He crept over to the table and seized hold of the

moneybags and made off with them, and neither the giant nor his wife

knew

anything about it until Jack was safe down the bean-stalk and home

again.

When

Jack’s mother saw the moneybags she was filled with wonder and joy.

“Those were

once your father’s,” said she, “but they were stolen from him, and

never did I

think to see them again.”

After

that Jack and his mother lived well, they had plenty to eat and drink,

and good

clothes to wear, and everything they wanted. And they were not stingy;

they

shared their good luck with their neighbors as well.

After

awhile the money was almost gone. “I’ll just climb up the bean-stalk

again,”

said Jack to himself, “and see what else the giant has in his castle.”

He

climbed and he climbed and he climbed, and after awhile he came to the

giant’s

country, and there in front of him lay the road to the castle. Jack

walked

along briskly, setting one foot in front of the other till he came to

the

castle door, and as he saw no one he opened the door and stepped inside.

There

was the giant’s wife scouring the pots and pans, and when she saw Jack

she almost

dropped the skillet she was holding.

“You

here again?”

“Yes,

here I am again,” said Jack.

“Then

I wish you were some place else,” said the giant’s wife; “when you were

here

before our moneybags were stolen, and I can’t help thinking you had

something

to do with it.”

“Oh,

oh! How can you think that?” cried Jack.

“Well,

be off with you, anyway”; and the giant’s wife spoke quite glumly. “I

want no

more strange lads around here.”

Yes,

Jack would be off in a moment, but wouldn’t she give him a bite of

breakfast

first?

No,

the giant’s wife wouldn’t, and that was flat.

But Jack

was not to be turned off so easily; he talked and begged and argued,

and while

he was still talking they heard the giant at the door.

The

giant’s wife was terribly scared, “Oh, if he finds you here won’t I get

a

beating!” she cried.

“Quick;

into the pot again!”

Jack

crawled into the copper pot and the giant’s wife put the lid over him.

The

next moment the giant stamped into the room.

“Fee,

fi, fo, fum,”

he bawled,

“I

smell the blood of an Englishman;

Be

he

alive or be he dead,

I’ll

grind his bones to make my bread!”

“Nonsense,”

said his wife, “you’re always fancying things. Here, sit down at the

table and

eat your breakfast. A crow flew over the roof and dropped a bone in the

fire, and

that is what you smell.”

The

giant sniffed about a bit, and then, still muttering to himself, he sat

down at

the table and began to eat. After he had finished he cried, “Now wife,

bring me

my little red hen from the treasure-room.”

His

wife went into the treasure-room, and presently she came back with a

little red

hen in her apron. She set it on the table before the giant. The giant

grinned

till he showed all his teeth.

“My

little red hen, my pretty red hen, lay,” said the giant.

As

soon as he said that the hen laid an egg all of pure gold.

“My

little red hen, my pretty red hen, lay!” said the giant. Then the

little red

hen laid another egg.

“My

little red hen, my pretty red hen, lay,” said the giant. Then the hen

laid a

third egg.

“There!”

said the giant, “that is enough for to-day. Now, wife, you can take her

back to

the treasure-room again.”

His

wife took up the hen and carried her off to the treasure-room, but when

she

came back into the kitchen she forgot to shut the treasure-room door

behind

her.

Then

the giant stretched his legs out in front of him and went to sleep and

snored

till the rafters shook.

His

wife worked around in the kitchen, and after awhile, when she wasn’t

looking,

Jack crept out of the pot. He crept over to the door of the

treasure-room and

slipped through, and there was the little red hen sitting comfortably

on a

golden nest.

Jack

caught her up under his arm and she never made a sound. Then he crept

back

through the kitchen and out through the door, and made off down the

road, and

the giant’s wife never saw him at all.

But

just as Jack reached the bean-stalk the hen began to cackle. This woke

the

giant. “Wife, wife,” he roared, “someone is stealing my little red

hen,” and he

ran out of the castle and looked all about him; but he could see no

one, for

Jack was already half-way down the bean-stalk.

After

that Jack and his mother never had any lack of anything, for whenever

he wanted

money he had only to say, “My little red hen, my pretty red hen, lay,”

and the

hen would lay a gold egg.

Still

Jack was not satisfied. He wanted to see what else was in the giant’s

castle.

So one day, without saying a word to his mother, he climbed the

bean-stalk and

hurried along the road to the giant’s castle. He did not want to meet

the

giant’s wife, for he thought maybe she had guessed that it was he who

had taken

the giant’s hen, and the moneybags, and so indeed she had, and what was

more

she had told the giant all about it, too.

Jack

crept up to the castle very carefully, and he saw no one. He opened the

castle

door a crack and peeped in, and still he saw no one. He pushed it open

a little

wider and then he ran in and across the kitchen and hid himself in the

great

oven.

He

had no more than done this before the giant’s wife came in. “Pfu!” said

she.

“What a draft!” and she closed the outside door. Then she set the

giant’s

breakfast on the table, still talking to herself. “The door must have

blown

open,” said she. “I’m sure I closed it when I went out.”

Presently

the giant came thumping and stumping into the house. The moment he

entered the

room he began to bawl —

“Fee,

fi, fo, fum!

I

smell the blood of an Englishman;

Be

he

alive or be he dead,

I’ll

grind his bones to make my bread.”

“What?

What?” cried his wife, “I found the door open just now. Do you suppose

that

dratted boy is in the house again?”

“If

he is, I’ll soon put an end to him,” said the giant.

The

giant’s wife ran to the copper pot and lifted the lid, and looked

inside it,

but no one was there. Then she and the giant began to hunt about. They

looked

in the cupboards and behind the doors, and every place, but they never

thought

of looking in the oven.

“He

can’t be here after all,” said the wife, “or we would have found him.

It must

be something else you smell.”

So

the giant sat down and began to eat his breakfast, but as he ate he

mumbled and

grumbled to himself.

After

he had finished he said, “Wife, bring out my golden harp to sing for

me.”

His

wife went into the treasure-room and came back carrying a golden harp.

She set

it on the table before the giant and at once it began to make music,

and the

music was so beautiful that it melted the heart to hear it. The giant’s

wife

sat down to listen, too, and presently the music put them both to

sleep. Then

Jack crept out of the oven and seized the harp and made off with it.

At

once the harp began to call, “Master! master! help! Someone is running

off with

me!”

The

giant started out of sleep and looked about him. When he found the harp

gone he

gave a roar like an angry bull. He ran to the door and there was Jack

already

more than half-way down the road. “Stop! stop!” cried the giant, but

Jack had

no idea of stopping. He ran until he reached the bean-stalk, and then

he began

climbing down it as fast as he could, still carrying the harp.

The

giant followed and when he came to the bean-stalk he looked down, and

there was

Jack far, far below him. The giant was not used to climbing. He did not

know

whether to follow or not. Then the harp cried again, “Help, master,

help!” The

giant hesitated no longer. He caught hold of the bean-stalk and began

to climb

down.

By

this time Jack had reached the ground. “Quick! quick, mother!” he

cried. “Bring

me an ax.”

His

mother came running with an ax. She did not know what he wanted it for,

but she

knew he was in a hurry.

Jack

seized the ax and began to chop the bean-stalk. The giant above felt

the stalk

tremble. “Wait! wait a bit!” he cried, “I want to talk to you!”

But

before he could say anything more the bean-stalk was chopped through

and fell

with a mighty crash, and as the giant fell with it that was the end of

him.

But

Jack and his mother lived in peace and plenty forever after.

BEAUTY

AND THE BEAST

There

was once a merchant who had three daughters. The two older ones were

handsome

enough, but the third was a beauty, and no mistake; her eyes were as

blue as

the sky, her hair was as black as ebony, and her cheeks were like

roses. The

merchant loved his two older daughters dearly, but this Beauty was the

darling

of his heart.

Things

went along pleasantly for a long time, and the merchant was rich and

prosperous, but then things began to go wrong with him. One after

another of

his ships was lost at sea, and a great part of his fortune with them.

One

day the merchant called his daughters to him and said, “My children, I

find it

will be necessary for me to go on a long journey. I am no longer a rich

man,

but I wish to bring home a gift to each one of you, so tell me what you

would

like to have.”

Then

the two older daughters began to think of all the things they wanted,

and each

was afraid the other would get something finer than she did.

At

last the eldest spoke, “Dear father,” said she, “I wish you would bring

me a

velvet robe embroidered with gold, and shoes to match, and a fan to

wave in my

hand.”

“And

I,” said the second, “would like a necklace of pearls, and pearls for

my hair,

and a fine bracelet.”

The

merchant was troubled that his daughters should ask for such costly

things, but

he did not like to refuse them. “And you, Beauty,” said he, turning to

his

youngest daughter, “what will you have?”

“Dear

father,” said she, “you have given me so much that I have nothing left

to wish

for; but if you bring me anything at all let it be a rose.”

When

her older sisters heard this they were very angry. They thought that

Beauty had

asked only for a rose so that she might shame them before their father,

and

make him think she was more unselfish than they were. But Beauty had

had no

such thought as that.

The

merchant smiled at his youngest daughter and kissed her thrice, but his

older

daughters he kissed only once. Then he mounted his horse and rode away.

He

journeyed on for several days, and at last he reached the city he was

bound

for. Here he found he had lost even more of his fortune than he had

thought. He

was now a poor man. Still he managed to buy the gifts his two older

daughters

had asked for, and then with a sad heart he set out for home.

He

had not journeyed far, however, when he was overtaken by a storm and

lost

himself in a deep forest. He rode this way and that, trying to find the

way

out, and then suddenly he came to an open place, and there he saw

before him a

magnificent castle.

The

merchant was amazed. He had never heard of such a castle in that

forest. He

rode up to the door and knocked, hoping to find shelter for the night.

Scarcely

had he knocked when the great door swung open before him. He entered

and looked

about, no one was there; everything was silent. Wondering he went on

into one

room after another. Everything was very magnificent and well arranged,

but

nowhere was a soul to be seen. At last he came to a room where a supper

was set

out. The plates were all of gold, and the fruits and meats were of the

rarest

and most delicious kinds.

The

merchant was so hungry that he sat down at the table, and at once the

food was served

to him by invisible hands, while soft music sounded from a hidden room

beyond.

He

ate heartily and then arose and went in search of a place to sleep.

This he

soon found. A bed had been made ready in a large chamber, and here he

undressed

and lying down he slept until morning without being disturbed.

When

he awoke he found his own travel-stained clothes had been taken away.

In their

place a handsome suit had been laid out, and other necessary things,

all of the

richest kind. There was also a bag filled with gold pieces. Wondering

still

more, the merchant arose and dressed and went out into the gardens to

look

about him. Here everything was more beautiful than any garden he had

ever seen

before. There were winding paths and fountains, and fruit-trees and

flowering

plants.

Beside

one of the fountains was a rose-bush covered with the roses. The sight

of these

roses reminded the merchant of Beauty’s wish, and he thought it would

be no

harm to break off one to carry to her. He chose the largest and finest

rose.

Scarcely had he plucked it, however, when the air was filled with a

sound of

thunder, the ground rocked under his feet, and a terrible looking beast

appeared before him.

“Miserable

man!” cried the Beast, “what have you done? All the best in the castle

was

offered to you. Why have you broken my rose-bush that is dearer to me

than

anything in the world? Now for this you must surely die.”

The

merchant was terrified. “Oh, dear, good Beast do not kill me!” he

cried. “I

meant no harm. Only let me go, and I will never trouble you again.”

“No,

no,” answered the Beast. “You shall not escape so easily. You have

broken my

rose-bush and you must suffer for it.”

Still

the merchant begged and entreated to be spared and at last the Beast

had pity

on him. “If I spare your life,” said he, “what will you give me in

return for

it?”

“Alas,”

said the merchant, “what can I give you? I have lost all my fortune and

I am

now a poor man. I have nothing left in the world but my three

daughters.”

“Give

me one of your daughters for a wife and I will be satisfied,” said the

Beast.

The

merchant was horrified at the thought of such a thing. He would have

refused,

but he feared that if he did so the Beast would tear him to pieces at

once.

“You

may have three months in which to think it over,” said the Beast. “But

you must

promise me that at the end of that time you will return here and either

bring

me one of your daughters or come prepared to die.”

The

merchant was obliged to promise this; he could not help himself. As

soon as he

had promised the Beast disappeared and the man was free to go, and this

he was

not slow to do.

He

rode on toward his home and his heart was heavy within him. He did not

see how

he could possibly give one of his daughters to be the bride of a

hideous beast

and yet he did not wish to die.

His

daughters met him with joy, and the two older sisters were delighted

when they

saw the beautiful gifts he had brought them. Only Beauty noticed his

sad and

downcast looks.

“Dear

father,” said she, “why are you troubled? Has something unfortunate

happened to

you?”

At

first her father would not tell her, but she urged and entreated him to

tell

her until finally he could keep silence no longer. He told his

daughters all

about the castle and his adventure there and of the Beast, and of how

unless

one of them would consent to marry the Beast he would have to lose his

life.

When

the older daughters heard this they were ready to faint. Not even to

save their

father’s life could they consent to marry such a creature.

“Dear

father,” said Beauty, “you shall not die. I will be the Beast’s bride.”

“Yes,

yes,” cried her sisters. “That is only right. If Beauty had not asked

for the

rose this misfortune would not have happened.”

To

this the merchant would not at first agree. Beauty was the dearest to

him of

all his daughters. He had hoped that if any of them was to marry the

Beast it

might be one of the older sisters. But they would not hear of this and

when, at

the end of three months, the merchant set out to return to the castle

he took

Beauty with him.

They

rode along and rode along and after awhile they came to the forest, and

then it

did not take the merchant long to find the castle. He knocked at the

door, and

it opened as before, and he and Beauty went in through one room after

another,

and everything was so magnificent that she could not but admire it. At

last

they came to the supper-room, and here a delicious feast was set out

for them.

They sat down and ate while soft music sounded around them. Beauty

began to

think the master of all this could not be such a terrible creature

after all.

But

scarcely had they finished their supper before the Beast appeared

before them,

and when Beauty saw him she began to shake and tremble, for he was even

more

dreadful looking than her father had said.

“Do not

fear me, Beauty,” he said in a gentle voice. “I will do you no harm.

Your

father has brought you here, and it is true that here you must stay,

but you

need not marry me unless you are quite willing to.”

“I do

not wish to marry you, Beast, and you must know that,” said Beauty.

“But I fear

that if I do not you may harm my father.”

“No,

Beauty, I will not harm him. He may go in peace, and perhaps after you

have

been here awhile you may learn to like me enough to marry me.”

Beauty

did not believe this, but the Beast spoke so gently that she no longer

feared

him and when the time came for her father to go she bade him good-by

and did

not grieve him by weeping.

After

that Beauty lived there in the Beast’s castle and was well content.

Every day

she went out into the gardens, and the Beast came and played with her

for

awhile, and she grew very fond of him. Every day before he left her he

said,

“Beauty, are you willing to marry me?”

But

always Beauty answered, “No, dear Beast, I do not wish to marry you.”

Then

the Beast would sigh heavily and go away.

One

day Beauty was sitting before a large mirror in her room, and she was

sad

because she had not seen her father for so long.

“I

wish,” said she, “that I could see what my dear father is doing at this

moment.”

As

she said this she raised her eyes to the mirror. What was her surprise

to see

in it the reflection of a room quite different from the one she was in.

It was

a room in her own home that she saw reflected there. She saw in it the

images

of her father and sisters. She could see them smile and move, and she

could

tell exactly what they were doing. She found she could watch them in

the mirror

for as long as she pleased and whenever she pleased.

After

this Beauty often came to sit before the mirror, and she had only to

wish it

and she could see her home, and all that was going on there.

But

one day when she sat down before the glass she saw that her father was

ill. He

lay upon his bed so pale and weak that Beauty was terrified. She jumped

up and

ran out into the garden calling for the Beast.

At

once he appeared before her. “What is it?” asked the Beast anxiously.

“What has

frightened you, Beauty?”

“Alas,”

she cried, “my father is ill. Oh, dear, kind Beast let me go to him I

pray, and

I will love you for ever after.”

The

Beast looked very grave. “Very well, Beauty,” he said, “I will let you

go, for

I can refuse you nothing. But promise me you will return at the end of

a week,

for if you do not some great misfortune will happen to me.”

Beauty

was very willing to promise this. The Beast then gave her a ring set

with a

large ruby. “When you go to bed to-night,” he said, “turn the ruby in

toward

the palm of your hand and wish you were in your father’s house, and in

the

morning you will find you are there. When you are ready to return do

the same

thing, and you will find yourself back in the castle again. And do not

forget

that by the end of a week, to an hour, you must return or you will

bring

suffering upon me.”

Beauty

did as the Beast told her. That night when she lay down she turned the

ruby of

the ring in toward the palm of her hand and wished she were in her

father’s

house, and what was her joy, when she awakened the next morning, to

find

herself in her own bed at home. She arose and ran to her father’s room,

and the

merchant was so delighted to see her that from that hour he began to

get

better, and in a few days he was as well as ever again.

Beauty’s

sisters asked her a great many questions about the castle where she

lived, and

when they heard how fine it was, and how happy she was there, they were

filled

with envy. “Beauty always gets the best of everything,” they said to

each

other. “She is younger than either of us, and see how finely she lives;

much

better than we do.” They then planned together as to how they could

keep Beauty

from going back to the castle at the end of the week. “If we can only

make her

break her promise to the Beast,” said they, “he might be so angry with

her that

he would send her away and take one of us to live at his castle

instead.”

The

day before Beauty was to return to the Beast they put a sleeping-powder

in the

goblet that she drank from.

As

soon as Beauty had swallowed this powder she became very sleepy. Her

eyelids

weighed like lead, and presently she fell into a deep slumber, and she

did not

awaken for two days and nights. At the end of that time Beauty had a

dream, and

in her dream she walked in the castle gardens. She came to the

rose-bush beside

the fountain, and there lay the poor Beast stretched out on the ground,

and he

was almost dead. He opened his eyes and looked at her sadly. “Ah,

Beauty,

Beauty,” he said, “why did you break your promise to return at the end

of a

week? See what suffering you have brought on me.”

Beauty

awoke, sobbing bitterly. “Alas, alas!” she cried. “I must go at once. I

feel

some harm has come to the Beast, and that it is my fault, though how I

do not

know.” For she did not know she had been asleep for two days and nights.

She

turned the ruby ring with the ruby toward the palm of her hand, and

wished

herself back in the castle and then lay down and went to sleep.

When

she awoke she was in the castle again, and it was early morning. She

ran out

into the garden, and straight to the rose-bush. There, as in her dream,

she saw

the Beast stretched out on the ground, and he seemed to be without life

or

breath. Beauty threw herself down on the ground and took his head in

her lap,

and her tears ran down and fell upon him, and it seemed to her she did

not love

even her father as dearly as she loved the Beast. “Oh, Beast — dear,

dear

Beast,” she cried, “can you not hear me? Are you quite, quite dead?”

Then

the Beast opened his eyes and looked at her. “Ah, Beauty,” he said, “I

thought

you had deserted me. Do you not yet love me enough to marry me?”

“Oh,

I do! I do love you enough, and gladly will I be your bride,” cried

Beauty.

No

sooner had she said this than the rough furry hide of the Beast fell

apart, and

a handsome young prince all dressed in white satin and silver stood

before her.

Beauty looked at him wondering. “Yes, you shall indeed be my own dear

bride,”

cried the Prince, “for you and you alone have broken the enchantment

that held

me.”

Then

the Prince, a Beast no longer, told Beauty that a wicked fairy had

changed him

into the shape of a Beast, and not until a fair young maiden would love

him

enough to be his bride would the enchantment be broken. But Beauty had

loved

him for his kindness and goodness in spite of his ugly form, and now

never

again could the wicked fairy have any power over him.

And

now all through the castle was heard a sound of life and of voices and

of

running to and fro. For the same enchantment that had changed the

Prince to a

Beast had made all his people invisible, and now, they too were freed

from the

spell.

Then

how happy Beauty was. If she had loved the Beast she loved the handsome

young

Prince a thousand times better. A grand wedding feast was prepared, and

her

father and sisters were sent for. Her father was given the place of

honor, but

it was quite different with her sisters; because of their hard hearts

they were

changed into two statues and they stood one on either side of the

doorway.

But

Beauty was too gentle to bear them any ill-will. After she was married

she

often used to go and stand beside the statues and talk to them, and her

tears

fell upon them so that after awhile their hard hearts grew soft and the

stone

melted back to flesh again. Then they were all very happy together. The

two

sisters were married to two noblemen of the court.

As

for Beauty and the Prince, nothing could equal their love for each

other, and

they lived together happy forever after, and no further harm ever came

to them.

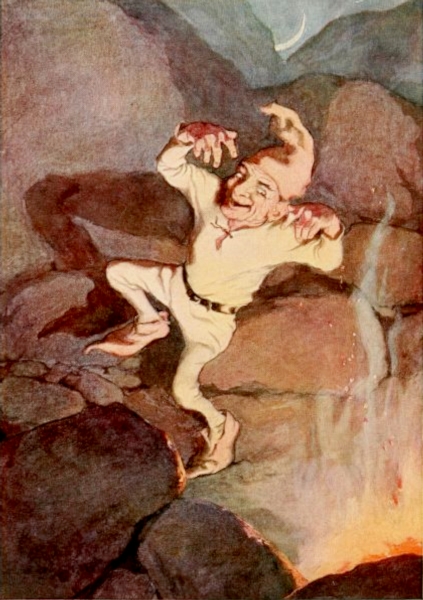

JACK-THE-GIANT-KILLER

There

was once a stout Cornish lad named Jack who had trained himself in

every sort

of sport. He could wrestle and throw and swim better than any other lad

in the

country; indeed there were few, even among the men, who could equal him

in

strength and skill.

At

that time there lived, on an island just off the coast of Cornwall, a

giant

named Cormoran. This giant was the pest of the whole land. He was

twenty feet

high, and as broad as any three men. People were so afraid of him that

when he

waded over from his island to the mainland they all ran and hid in

their

houses, and then he carried off their flocks and herds as he chose, and

asked

no leave of anyone. Seven sheep he ate at a meal, and three oxen were

not too

much for him. There was much complaining through the land because of

the way he

wasted it.

Now

Jack was as bold as he was strong, and he made up his mind to free the

people

from this scourge of a giant. He waited for a dark night when there was

no

moon, and then he swam from the mainland over to the island. The waves

were

high and the water cold, but Jack paid no heed to that. He took with

him a

pick, a shovel, an ax, and a horn.

As

soon as he landed on the island he set to work to dig a pit in front of

the

giant’s cave — a pit both wide and deep. The giant was asleep, for Jack

could

hear him snoring in his cave, and so he knew nothing of what was being

done by

the brave lad.

Toward

morning the pit was finished. Then Jack covered it over with branches,

and

scattered earth and stones over it so that no one could have told it

was any

different from the ground around it. After that he took his horn and

blew a

blast both loud and long.

The

sound awakened the giant from his sleep, and he sprang to his feet and

came

stumbling out from his cave. He glared about him and presently his eyes

fell

upon Jack.

“Miserable

dwarf!” he cried. “Is it you who has dared to disturb my sleep? Wait

but a

moment until I have my hands on you, and I will punish you as you

deserve!”

Jack

laughed aloud. “I fear you not!” he cried. “And as for punishing me,

you will

find that easier said than done.”

The

giant gave a cry of rage and sprang toward Jack, but no sooner did he

step upon

the branches that covered the pit than they gave way beneath him, and

he fell

down into the pit and broke his neck. There he lay without sound or

motion, and

seeing that he was dead Jack left him where he lay and swam back to the

mainland.

When

the people learned that the giant was dead and would trouble them no

more they

went wild with joy. Jack was hailed as a hero and a belt was given him

on which

were letters of gold that read —

“This

is the gallant Cornishman

Who

killed the giant Cormoran.”

And

now the lad was no longer called plain Jack, but Jack-the-Giant-Killer.

Now

many miles away in a deep forest there lived still another giant named

Blunderbore. This giant was full as strong and great as Cormoran had

ever been.

When

Blunderbore heard how the Cornish lad had killed Cormoran, and that now

he was

called “Jack-the-Giant-Killer” he was filled with rage. He swore he

would find

Jack and destroy him even as Cormoran had been destroyed.

But

Jack was no whit afraid. He had made up his mind to altogether free the

land

from giants; and he wished nothing better than to try his wits with

Blunderbore. So one day he took a stout oak in his hand and set out in

search

of the giant.

He

walked along and walked along, and after awhile he came to a forest,

and there

a cool spring bubbled up in the shade of the trees.

Jack

was hungry and thirsty, and tired too, so he sat him down by the spring

and ate

the bread and cheese he carried, and drank of the fresh water, and then

he

stretched himself out and went fast asleep.

He

had not been long asleep when the giant Blunderbore came by that way.

Blunderbore was very much surprised to see a youth lying there and

sleeping

quietly beside his fountain, for none ever before had dared to venture

here into

this forest for fear of him.

He

saw a glitter of golden letters upon a belt the lad wore, and stooping

he read

the words —

“This

is the gallant Cornishman

Who

slew the giant Cormoran.”

At

once the giant knew who Jack was, and he was filled with joy at the

thought

that now he had the lad in his power. He did not wait for Jack to

waken, but

swung him up on his shoulder, and made off with him through the forest.

Now

Blunderbore was so tall that his shoulders were up among the branches

as he

strode along, and the boughs whipped Jack in the face and woke him from

his

sleep. He was greatly amazed to find himself journeying along among the

leaves

on the giant’s shoulder instead of resting quietly beside the fountain.

However, he was not afraid. “I can do nothing at present,” thought he

to

himself, “but after awhile the giant will put me down, and then my wits

will

soon teach me a way to get the better of him.”

The

giant strode along without stop or stay until at last he came to a

great gloomy

castle and, this was where he lived. He carried Jack in through the

door into

the castle and up a flight of stone steps to a room that was directly

over the

outer doorway. Here he came to a halt and threw Jack down upon a heap

of straw

in the corner.

“Lie

there for awhile, my little giant-killer,” cried he. “I have a brother

who is

not only bigger and stronger than I am, but has more wits as well. I

will go

off and fetch him, and after he gets here then we will decide what to

do with

you.”

So

saying the giant left the room, and after locking the door behind him

he made

off across the hills in search of his brother.

No

sooner was Jack left alone than he began to examine the room. He

quickly

noticed that the door of the castle was directly under his window. In

one

corner of the room lay a great coil of rope. Jack took up this rope and

made a

slip noose in one end of it. This noose he hung from the window. The

other end

he passed over a great beam overhead. Then he sat down and waited for

the

monster to return.

He

did not have long to wait. Soon he heard the giant and his brother

talking and

grumbling together as they came up the road to the castle. He waited

until they

had reached the doorway and were directly under the window. Then he

dropped the

slip noose over both their heads. Quickly snatching up the other end of

the

rope he pulled with all his might and drew the two giants up into the

air,

struggling and kicking. He then leaned from the window and with his

sword he

cut off both their heads.

It

did not take him long after that to slide down the rope and get the

keys that

hung from Blunderbore’s belt. With these in his hand he reŽntered the

castle

and went all through it, unlocking door after door.

He

opened the giant’s treasure-chamber and found it full of gold and

silver and

jewels and all sorts of precious stuffs that had been stolen from the

people of

the land, for Blunderbore was a great robber.

In

the dungeons under the castle were many merchants and noblemen and fair

ladies

whom the giant had robbed and kept as prisoners.

When

these people found that Jack had come to free them, and that he had

killed the

giant, they were so glad and grateful that there was nothing they would

not

have done for the lad. Some of them wept for joy.

Jack

led them to the treasure-chamber and bade them take all they could

carry of the

treasures that were there. They would gladly have left it all for him,

but the

lad would have none of it.

“No,

no,” he said. “I have no need of riches, and if I were loaded down with

gold

and silver I could not travel about so lightly as I do.”

He

bade the grateful people good-by and journeyed on his way, leaving them

to find

their own way home, which, no doubt they all did in good time.

By

evening of the next day Jack was well away from Blunderbore’s forest,

and just

as he was wondering where he should find food and shelter for the night

he came

to a great house and saw a light shining from the windows.

He

knocked, and the door was opened to him by a giant with two heads. This

giant

was quite as wicked as either Cormoran or Blunderbore, but he was very

sly and

cunning. Instead of seizing Jack and throwing him into a dungeon he

made him

welcome. He set a hot supper before him, and talked with him

pleasantly, and

after awhile he showed the lad to a room where he could sleep.

But smiling

and pleasant though the giant was Jack did not trust him. He felt sure

the

monster was planning some mischief, so instead of going to bed after

the giant

left him, he stole to the door of the room and listened. He heard the

giant

striding up and down, and presently he heard him mutter to himself,

“Though

here with me you lodge to-night,

You

shall not see the morning light,

Because

I mean to kill you quite.”

“That

you shall not,” thought Jack to himself. “And if you think I am going

to get

into bed and lie there while you beat me with a cudgel you are

mistaken.”

He

began to feel about the room, and presently he found a great billet of

wood.

This he laid in the bed in his place, and drew the coverlet over it,

and then

he hid in a corner of the room.

Not

long afterward the giant opened the door. He crept over to the bed very

quietly

and felt where the billet of wood was lying under the covers. Then he

took his

club and beat it until, if Jack had been lying there, he would

certainly have

been pounded to a jelly. After that the monster went back to his own

bed well

satisfied, and slept and snored.

But

what was his astonishment the next morning when Jack appeared brisk and

smiling

and without so much as even a bruise upon him.

“Did

— did you sleep well last night?” stammered the giant.

“Oh,

well enough,” answered Jack, “but a rat must have run over the bed, for

I

thought I felt him whisk his tail in my face once or twice. I looked

for him

this morning, but I could not find him, so perhaps I dreamed it.”

When

the giant heard this he was frightened. He thought Jack must be a

wonderful

hero to stand such blows as his and scarcely feel them. However, he

said no

more, and the two sat down to breakfast together. The giant ate and

drank as

much as ten men, but Jack had hidden a leather bag under his doublet

and he

kept slipping the food into this as fast as the giant set it before

him. The

monster wondered and wondered that such a small man could eat so much.

After

breakfast Jack said, “Now I will show you a trick, and if you cannot do

the

same thing then you will have to own that I am the better fellow of us

two.”

To

this the giant agreed. Jack then took a knife and ripped open the

leather bag

that was hidden under his doublet.

“There!”

he cried. “Can you do the like?”

The

giant was amazed, for he never guessed that it was only a bag that Jack

had cut

open. However, he was not to be outdone. Catching up a knife he ripped

himself

open, and that was the end of him.

“The

world is well rid of another monster,” said Jack, and leaving the giant

where

he lay he set out in search of further adventures.

He

had not gone far along the road when he met a young prince riding along

without

any attendants to follow him. This Prince was the son of the great King

Arthur

of Britain, and he had left his father’s court and ridden out into the

world in

search of a lovely lady who had been carried off by a magician. This

magician

held her prisoner by his enchantments and it was to free her that the

Prince

had ridden forth alone.

When

Jack learned who the Prince was, and the adventure he was bent on, he

begged to

be allowed to go along as an attendant.

“That

is all very well,” said the Prince, “but if you travel with me you will

fare

hard indeed. I have given away all my money, and I do not know where to

find

food or even a place to sleep.”

“Do

not let that trouble you,” said Jack. “Not far from here lives a

three-headed

giant. He has a fine castle and a well-stocked larder. Only leave the

matter to

me and I will arrange it so that you can spend the night there and have

a fine

feast beside.”

At

first the Prince was very unwilling to agree to this. The adventure

seemed to

him a very dangerous one, but in the end Jack persuaded him to agree to

it, and

mounting on the Prince’s horse he set out for the castle, leaving the

Prince to

await him by the wayside.

Jack

rode briskly along and it did not take him long to reach the castle. He

knocked

boldly at the door.

“Who

is there?” called the giant from within.

“It

is your Cousin Jack, and I bring you news,” answered Jack.

The

giant opened the door and looked out. “Well, Cousin Jack, and what is

the news

you bring?”

Why,

the news was that a Prince and his company intended to spend the night

in the

giant’s castle, and were even then almost at the door. If the giant

were wise

he would flee away and leave the castle to the Prince. Then after the

Prince

and his company had gone the giant might safely return again.

But

no, the monster was not so easily to be scared out of his castle. “I

can drive

back five hundred men,” cried he, “so why should I be afraid?”

“Yes,

but can you drive back two thousand?” asked Jack.

“Two

thousand! Two thousand, did you say?” Why that was a different matter,

and if

the Prince were coming with two thousand men at his back, then it was

indeed

time for the giant to hide away. He then told Jack where there was a

secret

chamber all made of iron. There he would hide, and he begged the lad to

lock

him in, and not, for any cause to unlock the door until the Prince had

gone.

This

Jack promised. He locked the giant in the secret chamber, and then he

rode back

to fetch his master.

That

night Jack and the Prince feasted right merrily on the good things from

the

monster’s larder, and the next morning the Prince rode on his way and

Jack unlocked

the chamber door and let the giant out.

“What

a blockhead I am!” cried the monster as soon as he was free. “Yonder in

the

corner lie the cap of darkness, the cloak of wisdom, and the sword of

sharpness. If I had only thought of putting on the cap no one could

have seen

me, and I would not have had to hide in the secret chamber.”

“That

is true,” answered Jack. “But thanks to me you are safe at any rate,

and I

think I should be rewarded.”

He

then asked the giant to give him the cap, the cloak, and the sword, and

out of

gratitude the giant agreed right gladly. “They will be of more use to

you than

to me at any rate,” said the giant, “for when I need them most is the

time when

I forget all about them.”

Jack

took the cap, the cloak, and the sword and thanked the giant for the

gifts, and

at once set out after the Prince, whom he found waiting for him not far

away.

They

now journeyed on until they came to another castle where they hoped to

spend

the night. Here they were made welcome, and bidden to feast with the

noble lady

who was the mistress there. This lady was, indeed, the very one of whom

the

Prince was in search, but he did not know her, and she did not know him

because

of the spell of enchantment that was upon her.

After

the lady, the Prince, and Jack had feasted together the lady drew out a

precious handkerchief and passed it over her lips. “To-morrow,” said

she, “you

shall tell me to whom I have given this handkerchief in the night. If

you

cannot tell me this, you shall never leave this castle alive.”

The

Prince was greatly troubled when he heard these words, but Jack bade

him have

no fear. He waited until the lady left them, and then he put the cap of

darkness on his head and followed her, and she could not see him

because of the

cap. She did not know that anyone followed her, and she went out from

the

castle and along a path to the edge of a wood. There she was met by a

tall dark

man, and because of the cloak of wisdom which he wore, Jack knew this

man at

once as a magician.

The

lady gave him the handkerchief. “That is well,” said the magician.

“To-morrow I

will change this bold Prince into another marble statue to adorn my

hall. As to

his servant I will change him into a dog, a fox, or a deer as the fancy

strikes

me.”

“That

you shall not!” cried Jack, and drawing the sword of sharpness he

struck the

magician’s head from his shoulders with one blow.

At

once the lady was freed from the enchantment, and she looked about her

like one

wakening from a dream. She did not know where she was nor how she came

there.

Jack

led her back to the castle and no sooner did the Prince and she meet

than they

knew each other. They were filled with joy, and the Prince made ready

to take

her back with him to his father’s court. He wished Jack to come with

him, and

promised that if he would he should be made a great nobleman, but to

this the

giant-killer would not consent. He still had work to do in his own

country, and

he would never leave Wales until it was freed entirely from the pest of

giants.

So

the Prince and his lady bade Jack farewell, and rode away together,

while Jack

set out in search of further adventures.

He

had traveled a long distance, and night was falling when he heard

doleful cries

sounding from a wood near by. A moment later a giant came breaking out

from the

wood dragging a knight and a lady with him. He had captured them and

was taking

them with him to his cave.

Without

a moment’s pause, Jack put on his cap of darkness, and running up close

to the

giant he cut him down with one single blow of his sword. The lady and

the

knight were amazed. They had seen no one, and yet the giant had

suddenly fallen

dead, cleft through with a sword. They were still more amazed when Jack

lifted

the cap from his head and appeared before them. He then explained to

them who

he was, and how he had been able to kill the giant so strangely.

“This

is a wonderful story,” said the knight, “and you have saved us from

worse than

death.” He and his lady then begged Jack to come back with them to

their

castle, and to this he agreed, for he was weary with all his adventures.

When

they reached the castle, a great feast was made ready, and Jack was

treated

with the greatest honor. He sat at the knight’s right hand, and all the

best in

the castle was none too good for him.

But

while they were still in the midst of their feasting, a messenger

arrived in

great haste. His face was pale, and his teeth chattered with fear.

“What

is it?” cried the knight. “What is the news you bring?”

“The

giant! The great giant Thundel!” cried the messenger. “He has heard

that

Jack-the-Giant-Killer is here, and he is coming to destroy this castle

and all

who are in it.”

Even

the knight turned pale at this news, but Jack bade him have no fear. “I

had

intended to set out in search of this giant,” said he, “but now he has

saved me

the trouble.” He then asked the knight to send for a dozen stout

workmen. This

was done and Jack at once led the workmen out to the bridge that

crossed the

moat, and bade them cut the timbers almost through so that they would

only bear

the weight of one man, or of two at most. This bridge was the only way

of

entrance, and unless the giant crossed it he could not get to the

castle.

While

the workmen were still busy over their task, the giant appeared,

striding along

toward the castle. At once Jack slipped on his cap of darkness and

hurried out

to meet him.

The

giant could not see Jack because of his cap of darkness, but his sense

of smell

was very keen. He stopped short, and began to snuff about him like a

hound.

“Fee,

fi, fo, fum!

I

smell the blood of an Englishman;

Be

he

alive or be he dead,

I’ll

grind his bones to make my bread!”

cried the

giant.

“That

is all very well,” said Jack, “but first you will have to catch him.”

He then

jumped about from one side of the giant to the other. “Here! Here I

am!” he

cried. “Here to the right of you! No, to the left. Quick, quick, if you

would

catch me.”

The

giant turned first one way and then the other, clutching at the empty

air, for

Jack was invisible and so was easily able to keep out of his reach.

At

last the lad tired of the game. He looked behind him and saw that the

workmen

had finished their task and had retreated to the castle. He then caught

the cap

of darkness from his head and ran across the bridge. “Now, you

miller-giant,

who would grind my bones, catch me if you can,” he cried.

The

giant gave a bellow of rage and ran after Jack, who had already reached

the

other side. The timbers held till the giant was in the middle of the

bridge;

then, with a great crash, they gave way beneath him, and down he fell

into the

moat and was drowned. So Jack saved the lives of the knight and his

lady for

the second time, and freed the land of still another giant.

But

now came the most dangerous of all of Jack’s adventures.

Gargantua

was the greatest and most powerful of all the giants, and he was a

magician as

well. He lived on the top of a high mountain, and from there he would

come down

to rob and steal and carry off prisoners. These prisoners he changed

into

various sorts of wild animals, and he kept them in the gardens that

surrounded

his palace. He had carried off a duke’s only daughter in this way, and

had

changed her into a doe.

The

duke had been in despair over the loss of his daughter for she was his

only

child and he loved her dearly. He promised that anyone who brought her

back to

him should have her for his bride, and because she was very beautiful

many

princes and brave heroes had gone in search of her, but of them all

none had

ever returned.

It

was this dangerous giant that Jack determined to seek out and destroy.

He

girded the sword of sharpness at his side and took his cap of darkness

and his

cloak of wisdom and set out.

He

journeyed on and journeyed on, and after awhile he came to a high and

rocky

mountain, and at the very top of it he could see a great castle with

gardens

around it and high walls.

Jack

climbed up and up over rock and brier, stump and stone, until he came

to the

gate of the garden. There he stopped to put the cap of darkness on his

head;

then he ventured in.

The

gardens were very fine, as he saw at once, and many animals were

grazing on the

grass, or resting in the shadows. One of them, a beautiful doe, raised

its head

and looked toward him, then at once came over to him and rested its

head on his

arm, and looked up at him with its great dark eyes.

Jack

was very much troubled at this. He feared there was some enchantment

about the

place that made him visible in spite of his cap of darkness. However,

none of

the other animals paid any attention to him, so he hoped it was only

the doe

that could see him.

He

went on through the gardens until he came to the door of the castle,

and there

hanging beside it was a golden horn, and on the horn were these words:

“Whoever

doth this trumpet blow

Shall

soon the giant overthrow,

And

break the black enchantment straight,

So

all shall be in happy state.”

Jack

raised the horn to his lips and blew a blast so loud and clear that the

castle

echoed with it.

At

once a wonderful change came over the garden. The doe beside him

changed into a

maiden more beautiful than any Jack had ever dreamed of. The wild

animals

became princes and heroes and noble ladies.

As

for the castle itself, it fell into ruins; a great chasm yawned under

it, and

into this chasm it crumbled with a dreadful noise, carrying the giant

with it.

Then the ground closed over the ruins and not a single stone was left

to mark

the place where the castle had stood.

So

ended the last of Jack’s adventures, and so perished the last and most

wicked

of all his giant foes. From then on the land was at peace.

Jack

was married to the beautiful maiden who had followed him as a doe, and

as she

was the duke’s daughter the poor lad became very rich and powerful. He

and the

duke’s daughter loved each other dearly, and so they lived in great

happiness

all their lives, honored by everyone about them.

THE

THREE WISHES

Once

upon a time a poor man took his ax and went out into the forest to cut

wood. He

was a lazy fellow, so as soon as he was in the forest he began to look

about to

see which tree would be the easiest to cut down. At last he found one

that was

hollow inside, as he could tell by knocking upon it with his ax. “It

ought not

to take long to cut this down,” said he to himself. He raised his ax

and struck

the tree such a blow that the splinters flew.

At

once the bark opened and a little old fairy with a long beard came

running out

of the tree.

“What

do you mean by chopping into my house?” he cried; and his eyes shone

like red

hot sparks, he was so angry.

“I

did not know it was your house,” said the man.

“Well,

it is my house, and I’ll thank you to let it alone,” cried the fairy.

“Very

well,” said the man. “I’d just as lieve cut down some other tree. I’ll

chop

down the one over yonder.”

“That

is well,” said the fairy. “I see that you are an obliging fellow, after

all. I

have it in my mind to reward you for sparing my house, so the next

three wishes

you and your wife make shall come true, whatever they are; and that is

your

reward.”

Then

the fairy went back into the tree again and pulled the bark together

behind him.

The