| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

Some Haunted Houses and Their

Ghosts

By ANNIE M. L. HAWES IT IS IN the seaports of Maine, in the towns and villages that cluster about the curves of her broad bays, or stretch along the shores of her great tide water rivers that the most of her romances lie. Even in these places colonial houses are rare, and because Kittery, on the main shore of the beautiful Piscataqua, can boast of several in a distance of half a mile along a country road, the picturesque old town is dearly loved by the dreamer over New England romance and tradition. The Bray house, the oldest of these ancient landmarks, has been standing on the shores of Pepperrell Cove more than two hundred years, long before "the cove" received its name. It is a plain, unpainted two-story house with nothing in its exterior to tell its story to the passer-by. Master Bray, the builder and first owner of the house, came to America from Plymouth, the old Devonshire port of England, where he had been a boat-builder. He must have grown up with a head full of the New World, for Drake, Raleigh and Gilbert, and Sir Francis Champernowne, one of the first settlers in Kittery, were all Devonshire men, and Plymouth was the port whence they sailed and to which the first two brought back their spoils. There were plenty of old salts sitting about Plymouth docks when Bray was a youngster, telling how Elizabeth's fleet sailed away from the harbor to battle with Philip's Armada, of the daring Drake dancing off in his ship to capture Spanish galleons and bring home great emeralds and diamonds for the Queen's crown. They would remember, too, the little vessel in which "Eastward

from Campobello

Sir Humphrey Gilbert sailed;"

but most of all they must have talked of Raleigh, that other gallant young adventurer whom both men and women worshipped, and how he came back to Plymouth from his last voyage, old and broken, the reward of his king — the block. Perhaps it was Sir Walter s fate that embittered Plymouth against a crown. At any rate Charles found no help in Plymouth a generation later. Bray must have been a young man when the English block was stained by the King's blood, but he, too, was a Puritan. His trade must have been good in Plymouth, and I like to think of his boats floating out on the Hamoaze and the Catwater as those he afterward made in Kittery rode the waters of Pepperrell cove and Brave Boat harbor, but Indians are sometimes more satisfactory foes than bishops and kings, and when the next Charles came to his father's throne, John Bray sailed for America. Perhaps he hoped to make a fortune in the New World and go back to England. Perhaps Goodwife Bray died, still longing for her old neighbors and friends. At least it is certain Master Bray owned a house in Plymouth when he died, and was buried (nobody knows where) in the scanty soil of an unhallowed Kittery field instead of a deep-bosomed, yew-shaded Devonshire churchyard. A part of his Kittery house is unchanged. The tiny panes of iridescent glass, like those in the windows of some of the old houses in Boston's Beacon street, still twinkle in their mountings, and the buffet where Mistress Bray proudly displayed her "best dishes" is carefully preserved in a corner of the parlor. There is a curious figure painted on the inside of the buffet door — a cherubic creation consisting of head and wings, and much resembling those indescribable monsters by which early art-murderers in America disfigured the gravestones of their defenceless dead. This decoration antedates "the oldest inhabitant" and its origin remains a mystery. Possibly the Bray girls "hand-painted." *

* *

The house was divided among three owners at Master Bray's death. His will, dated January 22d, 1689, gave "Unto my loving wife Joan Bray the new end of my now Dwelling house in Kittery during the terme of her naturall life;" the middle of the house was bequeathed to "my sone John;" while Mary, a daughter unmarried at her father's death, had "the leanto and the chamber over it," and "the East room and as much of the chamber as is over that." The Brays were evidently an amiable family, or the head of the house would not have risked dividing one dwelling in three, and especially he would have avoided so delicate a division as we may guess was made from the wording of the will regarding the chamber over the east room. These boundaries are now lost, for the house originally ran back toward what is now the street, with a long roof sloping nearly to the ground. Perhaps this was "the leanto." Boats, cattle and land were also apportioned to Mistress Bray and her children, showing that Master Bray must have gathered much substance by his trade, and indeed the family had thought their Margery, who was but an infant when they left old Plymouth in 1660, quite too good for everybody and anybody to come acourting. This damsel grew up amid the hardships of early colonial life and the terrors of Indian warfare, for Philip's war waged during her young womanhood, and the Indians had an annoying habit of taking prisoners in such towns as Portland and Saco for long years after.

She was a very religious young person and as beautiful as she was good, seen through the mists of tradition. She was doubtless brought up "to reade, sew and knit with a reasonable measure of Catechism ;" as is set forth in the indenture papers of one Rachel! Palmer, who about this time was bound out, the tiny maid being then "three years and three-quarters ould." Margery's obituary notice — she died at 89 — says she was noted for her charity, her courteous affability, her prudence, meekness, patience, and her unweariedness in well doing." Everything goes to show her to have been the flower of the family, and as there has never been anything so attractive to a young man as a beautiful and good young woman, it is no wonder if the sailor lads of Piscataqua and the Shoals were madly in love with this wild rose of Kittery. In 1676 (one hundred years before the Revolution!) Joseph Pearce of Kittery made a verbal will, stating that after "all his debts was payed that ye remainder of his estate hee freely gave unto Margery Bray, daughter to John Bray of Kittery, shippwright," and further "begging very Earnestly of this Deponet that hee would not forget it, that shee might not bee cheated of it!" Joseph Pearce's relation to Margery is uncertain. It has been believed that he was a brother of Mrs. Bray, but he may have been only a neighbor who loved Margery, for we have evidence that lovers were not unmindful of the worldly estates of their choice in those days, as witness the forecasting of James Henry Fite. He made formal deposition before witnesses that if he should die suddenly "he gave unto his Girl, Innet McCulland, all the estate he had." James Henry's prudence was justified by the event. He was soon afterward killed by Indians, and Pearce, being a sailor, probably had reflected on the uncertainty of human life and made his will before starting away on a voyage. It is worthy of note that neither Fite nor Pearce restricted their legatees to "the use and enjoyment" of their property, as did many a husband of Kittery in making his will by the phrase "soe long as she shall remain my widow." The only Joseph Pearce who appears in history is Ellner Pearce's son to whom she gave by will, in 1675, a year before the deposition in favor of Margery was made, a house, land, cattle, "too featherbeds, too Hollande pillows, foure pewter platters of the biggest sort, too small basons, a candle stick and sault seller, one dripin pane, one grediron, one spitt with andirons and pott hangers," with "Meale ciues, silver spoones, Napkines, a warmeing pann," and other household furnishings, not to mention "a gould ring." But if this Joseph Pearce was the one who willed his goods to Margery, she evidently got neither the gold ring, the "halfe pint pott," "the beare bowl," the "Sillier Cupp," "silke Twilt," "Holland pillow beare," nor yet the "two skelletts" mentioned in Ellner Pearce's last testament, for years afterward when her husband sued in her name for an estate willed to her (and which I choose to think Pearce's) the case was given to the defendant, the costs of court being eight shillings and six-pence. So whether pretty Margery was "cheated of it," or whether Pearce was so sad a rollicker little was left after "his debts was payd" is not known. Is it a slander to think the latter, since, although Joseph's mother made him her executor, she also "did appoynt my loveing frejnd Mr. ffrans Hooke to take care yt my sonn do not waste or Imbessell the sd Estate." And it is the easier to believe that Joseph's heart and soul were not given to the accumulation of pence, from the fact that a man bearing his name had been obliged to leave his gun with John Bray as security for debt sometime before this. However, the Brays were well enough provided with this world's goods, and although Mrs. Bray seems to have been obliged to make her mark as a witness to Ellner Pearce's will, it was a fashion of the times, and none the less did the family look askance at a certain young Bill (or Boll as it is said his Welsh tongue made it) Pepperrell, who came over to consult Master Bray about boats much oftener than it seemed necessary, and when he made a formal proposal for Margery's hand, they put him off with the excuse that she was too young to wed. But William Pepperrell, the first, was no more daunted by the barriers of family pride, than was William the second by Duchambon's defenses at Louisburg. He left the unsavory Shoals (once forbidden by law as a residence for women or swine!) and came to Kittery Point. He showed himself a man of thrift and enterprise, time was in his favor, and when Margery was twenty years old, the Brays gave consent to the wedding, Master Bray giving his "sonn in law for euer, one Acre of Land" . . . "to begin from ye Wharf at ye water side, giveing lyberty if yr bee Occasion to make uss of ye Wharf, and so to runne backe leaueing the bujlding Yard, & to runne backe to ye highway, to a plajne place, neare the highway to place his house & so from ye house backward to ye Northwards till ye acre of Land bee accomplished." *

* *

To this acre Pepperrell and his sons added until their acres were numbered by the thousands and extended about them for many miles. In 1695 Pepperrell was a justice of the peace, signing himself "William Peprell Justes pes." In 1695-6 his signature is "Wm. Pepperel Is pece," and in 1698, when his illustrious, son was two years old, it appears as "Wm. Pepperrell, Justis pease." The Pepperrell house owes its fame to the fact that the second William Pepperrell, the hero of Louisburg, where he won his spurs and title fighting under the motto of the enthusiastic young White" field, "Nil Desperadum Christo duce," was born, lived and died within its walls. The house built by the elder Pepperrell was about thirty-seven feet square, says tradition. The younger man enlarged it, and both families lived in it until the father and mother died in 1734 and 1741. The house was shorn of its proportions long since, ten or twelve feet having been cut from either end, and there is little left to hint at its former grandeur, besides the grand hall into which the country neighbors used to say "you can drive a cart and oxen." The hall extends through the middle of the house and is about fourteen feet wide, finished in wood from top to bottom. The staircase is delightfully broad and easy and half way up is a landing ten or twelve feet square. An arched window on this landing has cherubs' heads carved on the two upper corners — grave stone cherubs, like the creature on the door of the Bray buffet. Sir William was an exact man, and his papers which might be likened to the leaves of the forest for multitude, were scattered far and wide after his death. His face (Mr. Parkman calls it a good bourgeois face, not without dignity, though with no suggestion of the soldier), is tolerably familiar through the portrait at Salem, Mass., painted in 1751, in London, and the copy at the state house in Augusta. Other men than Sir William have suffered defeat in their attempts to found a family, but somehow one has a particularly tender feeling for the luckless old baronet of whom history has only good to tell, when one reads his will, and never do the words of the preacher, "Vanity of vanities," rise more to the lips. His relatives evidently fattened on his prosperity, for to many of his kinsfolks he gives at his death the money they owe him — if they be already dead! But! if they are still in the body, and where a hand can be laid on them he is not always so lenient, and one of them is forgiven half his debt only, and that on condition that he pay the other half within two years to certain other relatives. The Baronet was a shrewd man, and no doubt he had bought a part of his wisdom in money matters with kinspeople by sore and repeated punishments. His only son, Andrew, was unhappy in his love affairs. There were rumors of a match between him and Mary, the daughter of Rev. Benjamin Stevens, who lived in the Congregationalist parsonage at Kittery Point from 1741 to 1791, and was an intimate friend of the Baronet, but Mary married another, and when Andrew, after many delays, went to Boston to marry Hannah Waldo, the Boston beauty refused to allow the ceremony to go on. Doubtless she had heard of Mary Stevens, and chose her own time to punish young Pepperrell for his procrastination. Six weeks afterward Miss Waldo became Mrs. Thomas Fluker, and their daughter, "the lovely Lucy," married Henry Knox, once the handsome Boston bookseller, afterward Washington's loved comrade in arms, and, still later, the magnate of Thomaston, in the Maine Waldo patent. Mrs. Knox is said to have been "a Tartar," a disposition, we may guess, inherited from the Waldo side of the family. Andrew died not long after his rejection by Miss Waldo, and his house on which his father had spent ten thousand pounds, has disappeared. It was used as a barrack during the Revolution, so the story runs, and was so injured it blew down in a great gale. Another legend says it was burned. After Andrew's death, Sir William's hopes turned to his young grandsons — the children of his daughter, Elizabeth Sparhawk. He does not seem to have been fond of his son-in-law, Colonel Sparhawk. The Colonel importuned him for private spoils while he was risking his life at Louisbourg, and it was vexatious to be teased for silver sets and hogsheads of wine by one sitting comfortably at home, while he with his bare-foot, ragged men, stood face to face with death. There is a significant clause in the Baronet's will. He there forgave Sparhawk "all the debt he oweth me," after which perhaps no more need be said of the relations of this much tried gentleman and his son-in-law. Sir William made every provision for the continuance of his name, arranging for its adoption by one and another of the four Sparhawk boys, or the little Mary Pepperrell Sparhawk, and in case they all died without issue, bequeathing it to more distant connections, but the grandson who became William Pepperrell, and for whom the title which expired at the Baronet's death was revived, went to England during the Revolution, the family estates were confiscated, and the family name lost. One or two of the fifty portraits of relatives and friends that once hung in Sir William's hall are in the Atheneum in Portsmouth, but the plate presented him in London while he was abroad after the fall of Louisbourg, went to England; this with his swords, gold watch, "Cloathing and armor and Gold Rings" as well as the "Diamond Ring in my Chest in Boston" all having gone to the Sparhawk children, none of whom seem to have inherited the grandfather's best qualities. There is a pretty story told of Mary. It is said that Mowatt went into Portsmouth harbor in 1775 with the intention of burning the town, but being entertained by the Sparhawks, and charmed with Mary, he spared Portsmouth and sailed away to wreck his vengeance on Portland, instead. Sir William, with his English traditions strong upon him, left money for the maintenance of a free school at Kittery Point, to be under the inspection of the Congregationalist minister of the parish; part of the income of the estate, failing heirs, was to be used for the church, and the tomb built by him in 1736 was to have proper care. This is one of the saddest parts of the story. In long years of neglect the tomb door had given away and adventurous boys played among the bones inside. A man of Kittery has told me he well remembers counting the skulls lying about the room — there were twenty-nine. While half a dozen school boys were in the mouldy charnel house, it was the delight of a big boy to light a bit of candle, and, suddenly blowing it out, shriek in the darkness that instantly enveloped the trembling urchins, "Old Pepperrell's coming — old Pepperrell's coming!" Woe then to the boy who was slow of foot for none stayed on the order of his going, nor to lend a hand to his neighbor. The tomb is now closed and cared for, but after all the pomp of his life, Sir William is still denied a gravestone, not even has his name been added to the inscription on the tomb. Fate has been kinder to his tiny niece, Miriam Jackson. Her ugly little slate headstone has stood close by the spot where the Pepperrells and Spar-hawks rest for more than one hundred and fifty years. Her life on earth was seventeen days. I have wondered if it was this little stone thrifty Sir William was bargaining for when he wrote to Boston for a tombstone, saying he would "not have it very costly," as being in a "country place it will not be much in view." The Baronet's father willed sixty "pounds in current money or Bills of Credit" to buy "Plate or Vessels for the Use" of the Kittery church, Sir William gave ten pounds sterling for the same purpose, and communicants in the little church at Kittery Point (it has but four male members) sip their sacramental wine and take their sacramental bread from solid silver, something rarely done in Maine. Sir William's money was devoted to the purchase of an armsplate, bearing his coat-of-arms, and an inscription embracing all his titles. The christening cup, modestly marked "The gift of an unknown hand," is supposed to have been given by Lady Pepperrell. Both the Pepperrell and Bray houses face the water. The street laid out years after they were built, passes under what were originally the back windows. It is said Sir William could mount his horse at his door and ride to Saco, without leaving his own land, and this is to be borne in mind while visiting the house he built for Mrs. Spar-hawk when she married at nineteen. *

* *

There was a clergyman away off in the Roger Williams Plantations who died, leaving a widow and two little boys. Young Mrs. Sparhawk, the widow, married Col. Waldo, and came to live in Boston. One of the boys, John, adopted his father's profession and live in Salem, the other, Nathaniel, became Sir William's importunate son-in-law, and it was his step-father's granddaughter who refused to marry his brother-in-law, Andrew Pepperrell. Mrs. Waldo made her will in Kittery in 1749, giving Col. Sparhawk, beside his half of her property, "all the plate of which I shall die possesse or shall not have disposed of and delivered in my life time to those to whom the same may be conveyed. And in case the Plate hereby given to my Said Son Nathaniel shall not be equal in value to that which my Said Son John has had aforesd, Nathaniel Shall have so much out of the rest of my Estate before Division as to make up that deficiency." Let us hope the Colonel was consoled by this will for his disappointment in regard to Louisbourg spoils, and that he ate and drank from silver the rest of his life. Mrs. Waldo divided her wardrobe between her two daughters-in-law, particularly mentioning a "suit of Masquerade Damask" for Mrs. Elizabeth, as she had already given Mrs. Jane a "suit of Silk Cloths," but to John's daughter she left one hundred pounds to be paid her when she should be twenty-one years old, or at her marriage, while no other grandchild is mentioned. John had named his daughter Priscilla, for his mother. "The Pepperrells could take care of the Sparhawk boys," doubtless good Mrs. Waldo said, no more seeing a generation into the future than do grandmothers of to-day. Colonel Sparhawk failed in business. Perhaps his neighbors suffered from his bad financial management. Perhaps they ate from pewter while he enjoyed silver. Perhaps he gave himself airs on account of his Boston connections, and his marriage with Sir William's daughter. It may have been not only from all these causes, but also because he was a Tory, that his memory is not revered in Kittery. The crest in his coat-of-arms is a sparrowhawk, and Kittery still tells of a lampoon one of his townsmen wrote after his death, on the Pepperrell tomb where the Colonel slept, regardless at last of plate: "Here

lies the hawk, who, in his day,

Made many a harmless bird his prey, But now he's dead and unlamented, Heaven be praised, we're all contented!"

A letter written by Sir William to order some of his daughter's "things" at the time of her marriage, has been preserved. It is dated "Pascataway in New England, Oct. 14th, 1741" (she was married the next May), and asks to have sent from England, "Silk to make a woman a full suit of clothes, the ground to be white padusoy and flowered with all sorts of flowers suitable for a young woman — another of white watered Taby, and Gold Lace for trimming of it; twelve yards of Green Padusoy; thirteen yards of lace for a woman's headdress, two inches wide, as can be bought for 13 s. per yard., He also ordered a handsome fan with leather mounting at twenty shillings, with two pairs of silk shoes, and "some cloggs" to be worn over them. Mrs. Sparhawk's house is about half a mile distant from her father's toward Portsmouth, and an avenue of fine trees once led from one to the other. The long approach from the road to the Sparhawk house is still bordered by trees, but the dusty highway worn by common feet runs between the old knight's mansion and the beautiful home where Mrs. Sparhawk received the grand guests coming in their own coaches from Boston and Portsmouth for the three days' visit prescribed by the etiquette of the mother country. This home is still delightful. The front door keeps its iron knocker and the bull's eye glass gleams above it. The broad hall ends in an arch under which one passes into a rear hall where Col. Sparhawk's leathern firebuckets still hang. Halfway up the wide, easy stair-case is a landing on which a tall clock stands. A window on this landing opens on a broad stair in the back staircase. The upper half of the window opens, and the lower sash drops to .a foot stool so that Mrs. Sparhawk's silken shoes might trip over the sill when she chose to steal slyly down the back stairs to catch the maids flirting with the fishermen whose boats were drawn up on the shore of Spruce creek behind the house. From Mrs. Sparhawk's window she looked across to the Pepperrell dower house, built for Lady Pepperrell after her husband's death. It is not as elegant as the Sparhawk house, but it is handsome and well-built; the floors are to-day the admiration of carpenters, while the staircase is not often equalled for width and ease of ascent. Halfway up is the landing, but here a door opens on the back stairs. One can fancy Mrs. Sparhawk advising her mother as to the advantage of a regular door instead of a window and a footstool, the one being troublesome to drop and the other liable to be misplaced by some mischievous maid who had her own reasons for delaying the mistress's coming; and then there was always the danger of catching one's slipper heel in the sill. The different parts of these houses, the furniture in them and the paper on the walls is supposed to have been made in England and brought to the "province of Mayn" in the Pepperrell ships. About the beginning of the present century Capt. Cutts, a rich ship master and owner, bought the Lady Pepperrell place and it is better known in Kittery as the Cutts house. Mrs. Cutts was a Chauncey, a descendant of Chauncey de Chauncey who crossed the channel with the Conqueror, a man who knew where the roots of his genealogical tree were, two hundred years before the battle of Hastings. *

* *

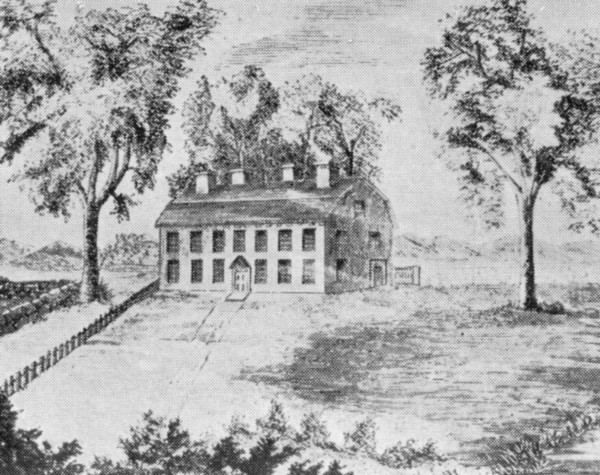

Charles Chauncey, the first of the name in this country, was born in England in 1596 and bought a divinity degree at Cambridge thirty-two years later. But the young divine had the boldness of youth, and, being fired with the ardent desire to reform the world, common to generous young minds, he dared to criticise Archbishop Laud openly, and such a course not being in conformity with the usages of the church, he was forced to apologize. Chauncey was a true Puritan, however. No sooner was the apology made than a terrible smiting of conscience ensued. Chauncey was troubled, this time, that he should "have so demeaned himself before a fellow worm," and he sorrowed more deeply for the apology than for the act which had called it forth. There was nothing left but flight to America. He soon acquired here a title which Boston people doubtless thought far more honorable than the prefix de — he became president of Harvard College, and Mrs. Cutts was descended from one of his six sons. Cutts is an old and honorable name in York county; Capt. Cutts was rich, his wife a lady, they were blessed with several children, and life must have looked fair to them, but blood was shed freely on the seas in those days, and tradition says a dying man on one of Capt. Cutts' vessels cursed the Captain, praying with his last breath that none of the family might die pleasant or easy deaths. Whether the Captain laughed or trembled at the threat, certain it is the embargo soon blighted trade, ships rotted at the wharves, and Capt. Cutts' fortune vanished. Two or three children had died in infancy. Mrs. Cutts died in 1812 — she was not a Cutts and the blight did not fall on her — but her unhappy husband lingered on until his ninety-eighth year, — almost half a century later — without having a lucid moment for years. One of the sons — a naval officer — shot himself as he lay on his bed in his father's house, another son lived a raving maniac for forty years, while Sally, the beautiful daughter, the darling of the family, is described most pathetically and lovingly as Miss Chauncey in Miss Jewett's "Deephaven." Happily she never realized she ate the bread of charity. She knew they were "a little reduced," but she always spoke hopefully of the time when their wealth would be restored to them, and she was always and under all circumstances the true lady — a Chauncey of the Chauncey de Chaunceys. Upon the mantel in a chamber of her old house recently stood a map of the world which she drew at school. That part of the globe we call the Antarctic was marked "the South Icy ocean," and Australia bore the name New Holland. The lettering and drawing were perfectly legible though it must have been seventy-five years since Miss Cutts' little fingers held the pencil that traced the lines, and the gilt frame (it seemed to be made of plaster) was partially fallen away. Side by side on the mantel with this relic stood a cabinet photograph of two laughing children. I turned it over and read on the back "Dolly Varden Saloon, Minneapolis." The contrast was sharp. What had the dainty lady in whose house I felt myself an intruder though she had long since left it, to do with the pert young civilization of to-day? The story of the Cutts home has always seemed to me the most romantic and pathetic of all the tales told of the old Kittery houses. One flat stone serves as a monument for the whole family in the old graveyard a few steps from the house. Sarah Chauncey, born 1791, died 1874, is the last name on the stone, and underneath is the single line "The weary are at rest."  The Governor Wentworth House  First Congregational Parsonage at Kittery Point where Rev. Dr. Benjamin Stevens resided 1741-1791 -- showing the Elm Tree planted by him *

* *

I shall always have an affection for another old Kittery house on account of a negress who lived in it. There were certain graves marked by common stones in the Pepperrell burial ground, guessed to be those of the negro servants, for though many negroes were held as slaves in Kittery, the graves of none of them are known. The ownership of the blacks in many cases was almost nominal, apparently. Sometimes they were given their freedom at the death of master or mistress, and in certain instances when the family was broken up, an old servant was made the care of the child with whom he or she chose to live. The elder Pepperrell mentions George, Scipio and Toby as slaves in his will, and Sir William directs that his wife have any four of the negroes she wishes after his death. But none of these have been as famous as Dinah, once an inhabitant of Gerrish Island. The Gerrish house in which she lived (there are still one or two known by that name in the town) stood on the outer shore of the Island, looking away over a splendid reach of sea, straight out to where the Shoals lie, a faint speck on the horizon. It was burned long ago, and Dinah is remembered by her attempts to reduce it to ashes half a century or more before it was destroyed. Dinah was charged with a trick of baking cakes of the fine wheaten flour and inviting her friends to midnight lunches when her mistress was out of the way, but the first time fire was discovered the sin of incendiarism was not laid to her account. At another time, however, when Mistress Gerrish was in her chamber cuddling a new baby, a young man coming home late from courting Sunday night, saw the glare of fire through the windows. He gave the alarm, and as the hastily summoned men dashed about with fire buckets, he spied Dinah idly looking on, and with sudden instinct called out, "Dinah, you black witch, what have you been doing?" Dinah's reply was a burst of tears, and the cry, "I wish to God they'd all burnt up!" The poor creature had a little son and in her ignorance she had fancied if she could destroy her owners, she and her child would be free. Alas for Dinah! Her master took her to York the morning after the fire and sold her and she died in the York poor house long ago at a very great age. This Gerrish house was probably standing in Sir William's time for Dinah's story was told me several years ago by a Mrs. Gerrish whose husband was the infant born about the time of Dinah's last trial for freedom by fire, and I remember Mrs. Gerrish said, "My husband would be just one hundred years old if he were living." *

* *

There are many more old houses near these I have mentioned. The quaint cottage once used as a Free Baptist parsonage, is more than a century old. In remodeling it lately the owner found a small brick in the filling under the hearth. It was marked in old-time figures, 1564. Another brick of ordinary size in a demolished chimney was marked 1776, but whether these are dates, and the first a cousin to the thin yellow bricks that pave the streets of Holland villages, is by no means certain. Another Cutts house, said to be far older than the one described here, stands where "ffrancis Champernown, Gentlemen" once had his home. This house modernized is Celia Thaxter's summer home, and hard by is the grave of "sweet Mary Chauncey," the subject of her poem "In Kittery Churchyard." A re-made blockhouse at the head of Fernald's Cove, opposite the navy yard, was the home of an ancestor of James Russell Lowell and the birthplace of William Whipple, who signed the Declaration of Independence. The "Commodore Decatur" house still occupied by Decaturs, is a neighbor to the Sparhawk mansion. Across the bay at New Castle is an old, old house where one Allen, boatswain for John Paul Jones, is supposed to have lived, and not far away is the rambling, fifty-roomed caravansary with its "Doors opening into darkness unawares, Mysterious passages and flights of stairs,"

where

the one time Martha Hilton and her aged co-partner, Benning

Wentworth, reigned in the days of the Pepperrells, the Governor and

the Baronet being, in the words of the country women, one year's

children.

In a secluded nook on the Kittery shore, away from the high road, an old house stands on its own decaying wharf, looking out past its ruined warehouses for the ships that will never come in. Twice a day, the eager tides rush up about the barnacled steps of its boat landing, questioning of the argosies that once lay waiting their service. Twice a day, baffled and perplexed, they steal silently back, leaving long streamers of dulse and weed to dry in the sun and wind, as on shore only tattered shreds are left to hint of the full tide of riches that once flowed over the land. Inside this old house are stores of lovely garments of the last century, parchments bearing the seal of a king Charles or George, ancient pictures, furniture and china that would drive a bric-a-brac collector to despair, since he has no charm that can make them his. In Portsmouth, just across the river, the proprietor of a shop for "antiques" showed me a blue silk umbrella, heavy enough for a giant and big enough for a small family. He assured me it was the veritable umbrella that wandered so long up and down the Kittery lanes. with Sally Cutts. |