| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

An Isle of the Sea

By ORRIE L. QUIMBY "Something hidden — Go and find it! Lost and waiting for you — Go!" "PRISCILLA," called Mistress Winter, in a harsh, raucous voice, like the cry of a sea-gull, "Priscilla, I say, already it is an hour since sun-up by the glass (hour glass) and you not yet come out of your bed!" Then, as no answer came from above, "The lazy wench! Now must I climb the stairs to waken her, or light the fire myself!" and she started up the steep, narrow stairway that led to the chambers, with a look on her face that boded ill for poor Priscilla. John Winter, sitting below in the long kitchen, heard her shrill voice berating the maid, then the sound of blows, and Mistress Winter came clattering down the stairway, her black eyes flashing and her sharp face flushed with rage. "The slattern! the fat, lazy slattern!" she stormed, "What think you, John Winter, she goes into my good feather bed with clean linen sheets upon it, without taking pains to pluck off her clothes! For a year and a quarter she hath lain with Sally upon my good feather bed, and now, Sally being lacke (away) three or four days to Saco, the trollope goes into bed in her clothes and stockings! Hereafter her bed shall be doust (dust) bed and sheets she shall have none!" "Truly, the maid is not of much service in this business," returned her husband, "but if she be beaten, she may be sending home ill reports, the which, if it come to the ears of Mr. Trelawney, would make much trouble for us." "Then must I forbear my hands to strike and rise rathe (early) in the morning to do all the work myself, or it will lie undone. And all the beating she hath had, hath never hurt her body nor her limbs." And she bustled about, piling sticks of firewood on the broad hearth. "If this maid at her lazy times, when she hath been found in her ill actions, doth not deserve two or three blows, who, I pray, hath most reason to complain, she or I? If a fair way will not do it, then beatings must sometimes upon such idle girrels as she is." Meanwhile she was hanging the kettle in the fireplace for the men's breakfast porridge, which she made of milk "boyled with flower," preparing great kettles of peas and pork, heaping bread on large wooden platters, drawing huge tankards of beer and ale, and all this without ceasing to enumerate Priscilla's shortcomings. "She cannot be trusted even to serve a few pigs but I must commonly be with her, or they will go without their meat. Since she came hither she could never milk cow nor goat, and every night she will be out-of-doors roaming about the island, after we are gone to bed, except I carry the key of the door to bed with me, and that I shall do henceforth, doubt not." John Winter, "a grave and discreet man," tried in vain to stem the torrent of her wrath, till, as she paused for breath, he broke in with, "Softly, softly, now Jane, for our minister, Mr. Gibson, is just without, in the palisatho (palisade) and it is not fitting that he should find you in so great a passion, lest he may judge, 'Like mother like child.' I have lately thought that he takes more than a passing interest in our daughter Sarah, and it is the desire of my heart that this might come to pass, as you well know." There was no time for further talk before the entrance of the Rev. Richard Gibson, A.B., scholar and gentleman, lately of Magdalen College, Cambridge, England, and the first settled minister within the limits of old Falmouth. Of him John Winter writes to his employer, "The Worshipfull Robert Trelawney:" "Our minister is a very fair Condition man, one that doth keep himself in very good order, and instructs our people well, if it please God to give us the grace to follow his instruction." He had been sent to minister to the plantation at Richmond's Island in 1636 by Robert Trelawney in response to this appeal from his brother, Edward Trelawney, who was temporarily in charge at the island: "But above all I earnestly request you for a Relligious, able Minister, for its moste pittifull to behold what a Most Heathen life wee live." Richard Gibson was an idealist by nature, and it is easy to understand the enthusiasm with which he entered upon his work in the New World. And that he had won a place in the affections of his people was evident from the pleading look Priscilla Bickford cast toward him, as, plump and comely in spite of red and swollen eyelids, she came down the stairs and began to help in laying the breakfast table. "Go you and serve the swine on the main land and carry these buckets of corn to the sows who have litters of young," ordered her mistress in a voice still sharp, despite her efforts at amiability. "It will be time enough to think of victuals when you have done some work, for idle girrels, who will not work, shall not eat." As Priscilla, going to pick up the buckets, passed the young minister, lie slipped two of the oaten cakes from the trencher on the table into her apron pocket, with a look of sympathy. "My patience is worren out with the girl," said Mistress Winter, as Priscilla went out. "Such a slattern that the men do not desire even to have her boil the kettle for them." Richard Gibson, probably made wise by previous encounters, made no attempt to intercede, but only remarked: "In this country we must of necessity work with such tools as God hath given us, as your husband can witness out of his own experience." "I have a company as of troublesome people as ever man had to do withall, both for land and for sea, and I have had no assistance heretofore from any that is here with me," said John Winter. "I have written to Mr. Trelawney that he may please make choice of honester and more pliable men, or else the plantation will all go to ruin, for here about these parts is neither law nor government. If any man's servants take a distaste against his master, away they go to their pleasure." "But notwithstanding all these difficulties you have wrought with some success," suggested Mr. Gibson. "Of a truth our building and planting have proved fairly well, with this strong palisatho of fifteen feet high and our ordnance mounted within on platform for our defense from those who wish us harm here. And we have paled in four or five acres for our garden also, planting divers sorts, as barley, peas, corn, pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, onions, garlic, radishes, turnips, cabbage, lettuce, parsley and millions (melons) and there is nothing we set or sow, but doth prove very well." "And the fisheries do surely prosper in large measure?" "I have sent great store of fish and train oil by the Agnes, also eight and one-half hogsheads of fish peas. As for our goats, I could willingly sell a score, for they overlay the island and on the main land the wolves do prey upon them. There be divers in these parts would have goats, but they lack money. The pigs increase apace, and grow fat on acorns and glames (clams) on the main land, though we have sustained the loss of many by the Indians, wolves, the harsh winter, and the idleness of them that had charge to look to them three times a week." Then as the men trooped in to breakfast, the talk became general and turned upon the new ship, a bark of thirty tons, now almost completed and ready for launching on the morrow. They spoke of what work remained to be done upon her, for as yet no masts or yards had been made for her, nor her deck calked. "She will be a stout, conditionable ship, I hope, for she has good stuff in her," said Arthur Gill, the shipwright, who had come from Dorchester to oversee the building of the ship. "She hath as good oak timber in her sides as ever grew in England." "I shall lack a master to go in her, since Narias Haukins, and his company are gone from here," responded John Winter. "I doubt she will lie still awhile for want of a master. He will need be a good plyer (navigator) for this coast." "With what cargo will she be laden and for what port?" asked Mr. Gibson. "The cargo may be wine and oil and mayhap some of our goods, such as hardware and the like. The best market will be in the Bay or the Dutch plantation or Keynetticoat, for in this part of the country they be good buyers but poor payers. Later on there will be voyages to Spain and the Canaries." As the men finished their meal and went out to begin the day's work, Richard Gibson lingered a little. "Will not Miss Sarah be returning soon?" he inquired, wishing to put Mistress Winter into good humor. "It were a pity she should miss the launching, for that should be a goodly sight." A look of satisfaction, quite unalloyed, overspread Mistress Winter's face at this mark of interest, for Sarah was the apple of her eye. "Sarah should be here before sundown to-day, Heaven be praised, and she brings with her a visitor from Winter Harbor, one Mary Lewis, lately come from England, whose father, Thomas Lewis, is a person of consequence in the settlement." Richard Gibson, though outwardly courteous, received the news with indifference, for his thoughts and aims were not concerned with maidens, nor did he seek prestige from acquaintance with influential persons. On the sensitive organization of the scholar, Mistress Winter had the effect of a wind from the east, and seizing his books he fled to a cranny in the rocks, where the only shadow was that thrown on the open pages of his cherished books by the wings of a sea-gull on its overhead flight. During the year he had spent at Richmond Island1 his love for the sea had grown and strengthened, and many blissful hours he had passed beside the swirling waters, the tang of the rockweed in his nostrils and the sand-pipers running along by the edge of the water for company. This was the cathedral wherein he worshiped and the crash and boom of the breakers on rocks and reef was to him like the music of mighty organ tones. But this was his last day of peace, for into this sequestered life came dainty Mary Lewis on her dancing feet, and the priest, saint and dreamer were merged in the man and the lover. The two girls arrived late in the afternoon, buxom, red-cheeked Sarah Winter, large-limbed and capable, fitted to be the mother of hardy pioneers, and Mary Lewis, slender and bewitching, like a blush rose, in her flowered gown, her eyes shining with the expectation of new worlds to conquer. There was not much time to make acquaintance that day, for at the time they arrived, the whole plantation was astir with a hue and cry, because the serving-maid, Priscilla, had not returned from the main land, whither she had been sent in the morning. "She hath gone a mechinge2 in the woods, I'll warrant you, as she did once before, the good-for-nothing hussy, and it would be a good riddance if the wolves or the Indians should make an end of her, say I!" was Madam Winter's pronouncement. But John Winter had no intention of leaving poor Priscilla to so hard a fate, and the whole company turned out to seek the truant. She was found after a long search but was stubbornly determined to spend the rest of her life in the woods and live on nuts and berries like the swine, rather than return to her hard-handed task-mistress. John Winter tried all his authority, but Richard Gibson finally turned the scale by reminding her that her mother in England needed the share of her wages which she was used to send and so induced her to return. Mistress Winter, by this time genuinely alarmed, greeted her almost kindly and peace once more reigned over the household. *

* *

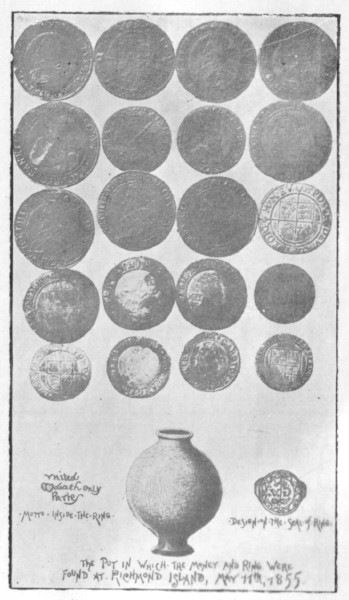

The new bark was launched on the following day, the tenth of June, 1637. In the early morning a thick mist covered the island and hung like a gray curtain between it and the mainland. But before breakfast was over it began to lift, breaking away, then shutting down again in fickle mood, till the sun came through the rifts, changing its dull grey to violet, and from violet to amethyst; familiar objects vaguely seen took on weird aspects, "suffered a sea-change," and the place seemed like an enchanted island. And without doubt, enchantment was there at work, for Mary Lewis fluttered about like one of the morning sunbeams. She exclaimed over the household arrangements, the big chimney place, of which John Winter says, "The chimney is large with an oven in each end of him, and he is so large that we can place our Chittle (kettle) within the Clavell pece (mantlepiece)." She admired the mill for grinding corn and malt, and quite won John Winter's heart by her interest in his garden and fisheries. "And the culverins within the palisatho, Mr. Winter, they are for defence against the Indians, undoubtedly?" she inquired. "They are for use against any who would do us harm but more especially were they set up against the pirate Dixy Bull, who took away from the plantation at Pemequid as much goods and provisions as is valued at five hundred pounds; and this Bull, if wind and weather would have given him leave, had an intent to come here to Richmond's Island, and to have taken away both provision and men, as they say." "Pirates! Mercy on us! But they might come back, who knows! Will you take care of me if the pirates do come again, Mr. Winter?" And the little witch, though she slipped her hand in John Winter's arm, glanced at the young minister, and as their eyes met, Richard Gibson felt that he could valiantly battle with all the pirates in the seven seas for another such look. At the hour fixed for the launching they all set forth in brave attire, John Winter in a suit of good kersey, "of a sad (dark) color," with long-lapelled waistcoat of brilliant scarlet, his small clothes fastened at the knee with silver buckles, over his "good Irish stockings" and wearing a steeple-crowned hat with broad brim; while Madam Winter and Sarah were gay in their scarlet petticoats and lace trimmed coats and waistcoats. Mary Lewis came tripping along on her high-heeled, London-made shoes, and lost no opportunity of showing the prettiest little foot in the world (Sarah wore number sevens). She needed a deal of help over the rocks and rough places, which was willingly given by the young minister, who was clad in gown and cassock, as became the dignity of his office. On the shore Arthur Gill had everything in readiness. As the masts were not yet set, the flags were fastened in place, the Royal Standard with its golden lions in the prow and the Union Jack flying from the stern. The cradle and launching ways were well greased and the shores so placed that a few blows would dislodge them. All being assembled the minister first invoked the blessings of God upon the bark, asking divine favour that she might safely ride the waves and weather the storms, that all her voyages might be prosperous and that "in all our works begun, continued and ended in Thee, we may glorify thy holy Name." As he ended, Sarah Winter, by her father's bidding, took her place by the prow, and as the master-builder knocked the shores from under the bark, she struck a small bottle of wine smartly against the stem of the vessel, saying in a clear voice, "I christen thee the Richmond."  Baptismal Font used by Rev. Robert Jordan at Cape Elizabeth The bark glided smoothly down the ways, and, as she entered the water, a great wave washed up on the shore, causing a lively commotion among those who had been standing too near the water. Mistress Winter had proudly turned to see what effect Sarah's part in the ceremony had produced upon Richard Gibson, when she saw him snatch Mary Lewis from before the incoming wave and carry her bodily to higher ground, while Sarah waded to dry land alone and unaided. "The pert little baggage!" she said to her husband. "I told you no good would come of it, but bound you were that she should come hither and the minister is fair bewitched with her already." And so it proved. Mary Lewis' visit was not an extended one, for a coolness on the part of her hosts made it none too pleasant, but for the short time she stayed, Richard Gibson was her devoted attendant and her whims were many. She must pretend she was an Indian squaw and try to dig clams upon the fiats; she must go out in the fishing boats and see them draw in the nets; she must try fishing with hook and line and some one must put the bait on her hook and praise her skill when, with ecstatic squeals, she actually drew in a mackerel from the midst of a whole school of them. And she told him what she had learned at Winter Harbor, how the Indians, taught by the Jesuit, Father Rasle, made the most beautiful waxen tapers from the berries of the bayberry, which she called wild laurel. Later on, she said, they would gather the berries, and at Michaelmas, his little church should be a blaze of light and sweet with the odor of the candles. She attended the church service on Sunday and heard him offer prayer, "that the inhabitants of our island may in peace and quietness serve Thee, our God." And he read the 107th Psalm, of "them that go down to the sea in ships and occupy their business in great waters." "He hath gathered them out of the lands from the east and from the west; from the north and from the south. He led them forth by the right way. Then they are glad because they be quiet, and so he bringeth them to their desired haven." And a sweet, new seriousness took possession of the girl, and still lingered in her face as they sat on the rocks at sunset, watching the crimson and gold brighten the western sky and then fade into mauve and gray, as the sun went down behind the dark firs and hemlocks. Encouraged by her changed demeanor, Richard Gibson told her of the high hopes and aims with which he had come to this new land; he grew enthusiastic over his work among the fishermen and spoke of his desire for a wider field of service. "Come then to the settlement at Winter Harbor," said Mary with an imperious air, "My father hath said that we have great need of a preacher there." "I greatly desire the continuance of my service here at the island and the people of the settlement might not favor it, that I should minister among them." "My father doth own the plantation jointly with Captain Richard Bonython, and moreover he will pay much money3 that we may have public worship, as is fitting. The people of the settlement will do what my father shall advise. And," with a little trill of laughter, "my father will do as I ask him," and all the mischief came back to her winsome face. Then springing to her feet, "The sun is gone," she cried, "we must hasten our ways, or Goody Winter's face will sour all the cream in the pans and the men will complain more bitterly than ever that she hath pincht them on the milk." As they hurried toward the house in the gathering dusk, "Why is that man digging in the ground over there by the heap of blackened timbers?" Mary asked, drawing a little closer to the minister. And looking where she bade him, Richard Gibson fancied he saw a gray, stooping figure among the ruins, but on nearer approach, there was no one to be seen. "Mayhap some one of our people hath been searching for Great Walt's buried treasure," he answered lightly. "Great Walt? and buried treasure?" said the girl, clinging to his arm and looking over her shoulder with a little shiver. "I am fain to hear that tale." So he told her the tragic story of Walter Bagnall, "sometime a servant to one in the Bay," who settled on the island as a trader in 1628, "a wicked fellow, who had greatly wronged the Indians," according to Governor Winthrop; told how he was slain by the Sagamore Squidraset and his company, who stealthily crossed from the main land in the darkness of night, and how they had taken his guns, and such goods as pleased them, then, having set fire to the house, had slunk back across the bar with their plunder by the light of the flames; told also how an expedition from the Bay sent to punish the murderers, seized Black Will, an innocent victim, who was enjoying a clam bake at the island, and on the principle of "an eye for an eye" (and no matter whose eye) hung him for a crime of which he knew nothing. "And the buried treasure, what of that?" asked Mary. " 'Tis said he had a great store of gold and silver4 and there hath been talk of a ring — a signet left in pledge by one in great necessity. Whatever became of them no one knoweth." "Tomorrow we will go to search and if, mayhap, I find the ring, then finding is having, but if you should chance to find it, then you shall give it to me!" announced the girl jestingly. "A bargain! in truth, for it was a wedding ring and there were graven in the ring two hearts, 'United,' and 'Death only partes.' Wouldst thou wear such a ring for me, sweetheart?" and there was no hint of jesting in the man's deep voice. "Sweetheart, indeed!" with wide-eyed innocence and drawing back from his arm. "And you as good as promised to Sarah Winter!" "I do protest there is nothing of the sort between us nor hath ever been. Though I have sometimes feared that her father's desires might incline that way," he admitted, wishing to be quite honest in the matter. "They do so no longer, then," said an angry voice within the palisade, for they stood talking just without. "Sarah shall have a man worth ten such white-faced weaklings as you, and I would say it if you were the Bishop of London, himself! And as for that trollope, she goes home to her father to-morrow and good riddance to bad rubbish! 'Tis a pity you know not the tales they tell of her carryings-on on ship-board — those who came from England with her!" and with this parting shot Dame Winter flounced into the house. "Take no heed of her ill talk, Mary, but tell me, would you wear my ring?" pleaded Richard Gibson, and it was a very demure little maiden who answered him. "For that you must speak with my father, when you come to Winter Harbor." And he, remembering what she had so lately said, "My father will do as I ask him," took heart of grace, and followed her into the house. On the following day Mary Lewis returned to Winter Harbor, and it was not many days before Richard Gibson made his appearance there. She must have led him a merry chase, but in the summer of 1638, John Winter wrote to his patron, Robert Trelawney, concerning Mr. Gibson, saying: "He is now, as I heare say, to have a wife and will be married very shortly unto one of Mr. Lewis' daughters of Saco." About the same time Richard Gibson, writing to Trelawney regarding an allotment of land to "Sitt down upon," says: "But the truth is, I have promised myself to them at Saco six months yearely henceforth, and further than that six months I cannot serve you after my time is out. Your people here were willing to have allowed me twenty-five Pounds yearly out of their wages so I would continue amongst them wholly. And I was glad of the means and thought that I had done God and you good service in bringing them to that minde, where they might have been brought further on. But Mr. Winter opposed it, because hee was not so sought unto (consulted) as he expected." He goes on, "It is not in my power what other men thinke or speak of me, yett it is in my power by God's grace so to live as an honest man and a minister, and so as no man shall speak evil of me but by slandering, nor think amisse but by too much credulity, nor yet aggrieved me much by any abuse." Evidently Mr. Gibson was having troubles of his own, but he met them like a man, saying "It shall never do me hurt more than this to make me looke more narrowly to my wayes." Mary Lewis and Richard Gibson were wed, in spite of gossips and mischief-makers, shortly after this time, for in January, 1639, he writes to Governor Winthrop: "By the providence of God and the council of friends I have lately married Mary, daughter of Mr. Thomas Lewis of Saco, as a fitt means for closing of differences. Howbeit, so it is at present, that some troublous spirits out of misapprehension, others as it is supposed for hire, have cast an aspersion upon her."5 He asks the Governor to call before him certain persons in Boston, who came over in the same ship with her, as to the truth of these accusations, adding, "If these imputations be justly charged upon her I shall reverence God's afflicting hand and possess myself in patience under God's chastening." In the following summer, July 10, 1639, John Winter writes to Mr. Trelawney: "Mr. Gibson is going from us; he is to go to Pascattawa to be their mynister and they give him sixty Pounds per yeare and build him a house and cleare some ground, and prepare yt for him against he come." Mr. Winter has no word of regret or explanation, but Stephen Sargeant, shipwright and a man of importance on the plantation, writes to Trelawney: "Mr. Gibson hee is going to Piscataway to live, the which wee are all sorry, and should be glade of that wee might injoy his company longer." Richard Gibson himself writes to his patron upon money matters, for apparently having a wife to support is expensive business. He wishes to have five Pounds which has been promised him, and also twenty shillings which is due him from Mr. Chappell's men, but which Mr. Winter withholds and will not allow him, and he continues: "For the continuance of my service att the Island, it is that which I have much desired and upon your Consent thereunto, I have settled myself into the Country and expended my estate in dependence thereupon: and now I see Mr. Winter doth not desire it, nor hath not ever desired it, but since the arrivall of the Hercules he hath entertayned mee very Coursely and with much Discurtesy, so that I am forced to remove to Paschataway for maintenance, to my great hinderance, which I hope you will consider of, To be unburthened of the charge my diett and wages putts him to, will not (When the summe of all is Cast up) amount unto so much case as he imagineth, but it is a Case which you know not nor can remedy."  Pot with Money and Rings Found at Richmond Island in 1855 In 1642 he was preaching to the fishermen at the Isle of Shoals. He was prosecuted by the Massachusetts Government for administering the ordinances of the Church of England, but was released without either fine or imprisonment, "he being about to leave the country," as Governor Winthrop said, feeling it incumbent upon him to apologize for his laxity in this case. *

* *

So Richard Gibson and Mary, his wife, sailed away from the shores to which they had come with such high hopes and whatever he may have lacked or left undone, we know that, like the Master he served, "the common people heard him gladly." His successor at the Island was a man of different fibre. Robert Jordan of Baliol College, Oxford University, son of Edward Jordan of the city of Worcester, of plebeian rank, was first and foremost a man of force and indomitable spirit. While Richard Gibson sought a kingdom not of this world, this man who came after him, wished for something substantial in this life and instinctively grasped the potential advantages of every situation; whatever came between him and the object he sought to attain was swept from his path, but the power he gained was used for worthy ends. He was a man of influence in the town of Falmouth for six and thirty years, and his descendants are like the sands of the sea shore, which cannot be numbered. John Winter writes to Trelawney, "Heare is one Mr. Robert Jordan, a mynister which hath been with us this three moneths, which is a very honest religious man by any thing as yett I can find in him. I have not yett agred with him for staying heare but did refer yt tyll I did heare some word from you. We weare long without a mynister and weare but in a bad way, and so we shall be still yf we have not the word of God taught unto us som tymes. He hath been heare in this country this two years and hath alwaies lived with Mr. Purchase, which is a kinsman unto him." He became John Winter's right hand man and, quick to seize the opportunity which Richard Gibson had not appreciated, he paid court to Sarah Winter and they were married some time during the winter of 1644. John Winter, writing to his daughter, Mary Hooper in England, speaks of six pounds in money which "your Sister Sara desires you would bestow in linen cloth for her of these sortes: some cloth of three quarters and a half quarter broad & some of it for Neck Cloths, and some for pillow Clothes, for she is now providing to Keepe a house. She hath been married this five months to one Mr. Robert Jordan, which is our minister." From this time on Robert Jordan took an active part in the affairs of the plantation and the town and eventually succeeded to the whole of the Trelawney estates in the Province. For Robert Trelawney, persecuted by political enemies during the long contest between Charles I. and Parliament, "a prisoner, according to the sadness of the times," as he says in a codicil to his will, and being deprived of "even ordinary relief and refreshment," died in prison at Winchester House, probably in 1644, at the early age of forty-five years. John Winter's death occurred during the same year, he naming Robert Jordan as his executor. The affairs of the plantation were found to be much involved, and three years later Robert Jordan petitioned the General Assembly of Ligonia, representing that he had "emptied himself of his proper estate" in paying Winter's legacies, and that the "mostness" of Winter's estate was in the hands of the executors of Robert Trelawney. He asks that "he may have secured and sequestered unto himself and for his singular use what he hath of the said Trelawney in his hands." Jordan's claim against the estate amounted to more than twenty-three hundred pounds while the whole plantation was appraised at only six hundred pounds. Four years after Winter's death the General Assembly of Ligonia gave Jordan all of the Trelawney property, real and personal, in the Province. He shortly after removed to the Cleeves house at Spurwink and dwelt there for more than thirty years, administering his affairs and maintaining his stand as a churchman, while Sarah, his efficient wife, sewed his white linen neck cloths and looked after the comfort of the household. He was forbidden by the Puritan government of Massachusetts to baptize or marry, but paid no attention to the order and was twice arrested and imprisoned by order of the General Court of Massachusetts. Posterity is especially indebted to him for the stand he took in the matter of witchcraft. That 6"there was never a prosecution for witchcraft to the eastward of the Piscataqua River, is probably due to the cool head and clear commonsense of the Rev. Robert Jordan." Parson Hale of Beverly, in a book entitled "A Modest Enquiry into the nature of Witch craft," A. D. 1697, writes as follows: "We must be very circumspect lest we be deceived by human knavery as happened in a case nigh Richmond's Island Anno 1659. One Thorpe, a drunken preacher, was gotten in to preach at Black Point under the appearance and profession of a minister of the gospel, and boarded at the house of Goodman Bailey, and Bailey's wife observed his conversation to be contrary to his calling, gravely told him his way was contrary to the Gospel of Christ and desired him to reform his life, or leave her house. So he departed from her house, and turned her enemy and found an opportunity to do her an injury. "It so fell out that Mr. Jordan of Spurwink had a cow die and about that time Goody Bailey had said she intended such a day to travel to Casco Bay. Mr. Thorpe goes to Mr. Jordan's man or men and saith the cow was bewitched to death, and if they would lay the carcass in a place he should appoint, he would burn it and bring the witch: and accordingly the cow was laid by the path that led from Black Point to Casco, and set on fire that day Goody Bailey was to travel that way, and so she came by while the carcass was burning, and Thorpe had her questioned for a witch: but Mr. Jordan interposed in her behalf and said his cow died by his servants' negligence, and to cover their own fault they were willing to have it imputed to witchcraft. Mr. Thorpe knew of Goody Bailey's intended journey and orders my servants (said he) without my approbation to burn my cow in the way where Bailey is to come: and so unriddled the knavery and delivered the innocent." Robert Jordan fled from Spurwink at the time of the Indian attack upon the settlement at Casco and lived at Great Island, now Newcastle, at the mouth of the Piscataqua until his death in 1679. During the Indian wars Richmond Island was left uninhabited, the buildings fell into decay, until to-day it lies desolate and forsaken, save for one lone house occupied by a caretaker, and a fisherman's shack on the further beach. As it lies there, somewhat grim and forbidding, while the waves splash upon its rocky shores and the sea-birds call and cry around it, it has the appearance of having withdrawn itself to brood upon days when it was trodden by many busy feet, and when abundant harvests waved above it, almost three hundred years ago. *

* *

Our daily bread is sweeter, the fruits of the earth more plenteous, and its flowers more fragrant and fair, because of those who lived and labored centuries ago. Phantom-like we see them move, trailing dim garments along the horizon of the world. From the mists of the sea, they beckon with the lure of mystery; through the years that intervene, we seek their half-obliterated foot-prints, while the surges of the sea still bemoan their woes, and all the winds of heaven whisper fragments of their secrets. *

* *

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I am indebted for material chiefly to the Trelawney Papers, by James Phinney Baxter, A.M. Also to William Goold's "Portland in the Past," Wm. Willis' "History of Portland," Folsom's "Biddeford and Saco," Gov. Sullivan's "History of the District of Maine," and to Gov. Winthrop's Journal.

_____________________ 1 Richmond Island lies off the coast of Cape Elizabeth and is connected with the main land by a sand bar, one-half mile in length, which is fordable at low tide. It comprises about two hundred acres, is three miles in circumference. and at the time of these happenings, was held by "Robert Trelawney and others" under the Trelawney patent, granted by the President and Council of New England, December 7th, 1631. His object, according to Edward Trelawney, his brother, was the "true setting and furthering of a Plantation to future posterity." The business carried on was that of fisheries and trading, ship-building, planting and raising of cattle, goats and swine. It was conducted by John Winter, agent, whom Josselyn describes as a "grave and discreet man, imployer of 60 men upon that design (fishing)." — Trelawney Papers. — James Phinney Baxter, A.M. 2 "To miche, or secretly hide himself out of the way, as truants do from school." — Minshew. — Trelawney Papers. 3 Thomas Lewis was taxed three pounds for the support of public worship. — Sullivan's History of Maine p. 218. Folsom's History of Biddeford and Saco. 4 A stone pot of beautiful globular form was ploughed up at Richmond Island, May 11, 1855. It contained gold and silver coins to the value of one hundred dollars and a signet ring engraved with two joined hearts, the words "United" and "Death only partes." 5 In 1640 Gibson brought action in Georges' Court against John Bonighton for slander in saying of him, in dwelling house of Thomas Lewis, deceased, that he was a "base priest, a base knave, a base fellow," and also for gross slander against his wife, and received a verdict for six Pounds, six shillings, eight pence and cost twelve shillings, six pence for the use of the Court. — York Records. 6 (Gov. Sullivan, Hist. of the Dist. of Maine P. 212.) |