| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

THE SETTING OF A

COTTAGE PLANNING the future

is a joy which enters too seldom into the American life. The setting of the

cottage is a matter of importance. It may be that the

next generation of youth, when tempted to leave the home acres will find the

beauty of those acres turn the scale toward continuance in the house where they

were born. He who plants an oak tree near a homestead provides by that act,

which perhaps occupies five minutes, a constant pleasure that may continue for

a thousand years. In "Looking Seaward" (p. 35) we have an instance in

which the owner planted or at least permitted to grow, an apple tree at the

cottage gable. He already had his view of the bay with winding shore and a

never-ending play of clouds. The addition of this apple tree should be enough

to influence the growing generations. The picture of it must remain in their

minds though they travel far. Maybe it will bring them back to the old home

though their feet have wandered into distant states. Beautify, therefore, the

cottage surroundings. To do so is to reap dividends in home lovers so numerous

that no financial investment is comparable. Have an apple tree at the end of

the house and at the back door. Place a couple of oaks at some distance from

the other end. Provide a square of elms in the rear. Let the graceful

horse-chestnut, the linden or the locust find their places at intervals in

front. Preserve an old stone wall with a corner not too far from the dwelling.

Along this wall serving as a wind break, coax the hollyhock and the larkspur to

grow. Between the back door and the vegetable garden let there be a natural

path bordered by low-growing flowers so arranged as to show at least one row of

brightness all the summer long. Let there be a seat hewn from an old stump

placed at the foot of the apple tree where the garden begins. Then be of good

cheer, look pleasant because you feel pleasant, and pray. Perhaps the boy will

not leave home. If, however, he goes, will he find anything better? Beside

these home charms there will be memories of affection, and the two attractions

should prove sufficient to bring him back. We have not over much sympathy with

the mothers who are singing "Where is my wandering boy to-night?", if

they have allowed their homes to be ugly. We suggest beauty as a lure to hold

wandering feet. It has often proved sufficient in the past. Is its power

broken? "Apple and

Dandelion Fluff" (p. 139) is in the rear of a quiet little home. The scene

is beautiful in itself and beautiful in its suggestion. There is the harbor,

the blossom, with its present beauty and luscious promise, there is the grass

and the fairies. seed of the dandelion. Is this not a better place to play than

a street full of dashing vehicles? The shade of these trees is even a call to

read. The seclusion invites thinking. We ought to set traps like this for our

young people. If the home is made too attractive to leave, most of the youth,

who are worth holding will be bene-fitted. Whether they are worth holding will

depend very much on the physical surroundings, that is, the setting of the

cottage. The daughter would be very dull who could not feel the charm of such

environment. It is part of good religion to create a home from which it is

difficult to get away. Mill owners used to be contented with barracks for their

workers. Unhappily, mill workers have so long lived in barracks that they may

not know what they are missing. What a delight it is to find occasionally a

village manufactury around which detached cottages with their fruit trees are

nestled. For the most part land is very cheap in such locations. It is

intolerable that a manufacturer should be so blind to his opportunity as to

erect unattractive cottages. Would strikers as soon leave the village with

cottages enbowered in blossoms and shade as they would leave a bare barrack?

Manufacturers should use the lure of beauty to keep their help with them. We

have tried everything else in our civilization except common sense. We have

tried all sorts of religion except a simple one. It was a seven years. wonder that a resident of Fifth Avenue kept a cow tethered on his lawn. Probably that cow cost a ground rent of many thousands a year. There are many things that city people cannot. have. They choose their own course. Neither Fifth Avenue nor even Central Park has anything like "Maine in Spring" (p. 99). Behind the fluffy blossoms is a Maine pine, and beyond the pure water of the pool there are maples, oaks and evergreens. The picture is a type of Maine. Its pine, singing its quiet song in winter and summer, and affording its protection on the north, to the bloom and the fruit! Count the petals, note their shading from white to pearl and to rose pink. Lie under the pines on the springy turf. Watch the reflections, broken now and then by the water that wrinkles its face when the wind kisses it. Then if you wish to return to New York, there is no soul left in you. THE STATE HOUSE, AUGUSTA THE COUNTRY

PARSONAGE

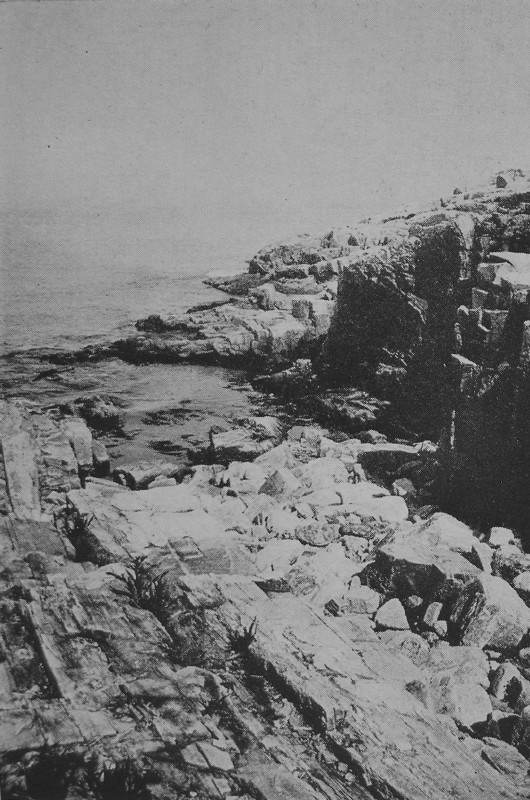

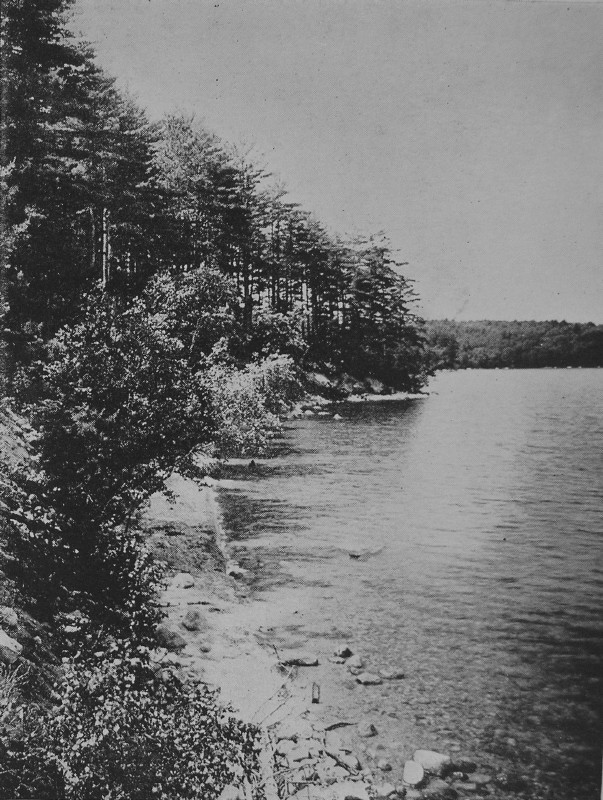

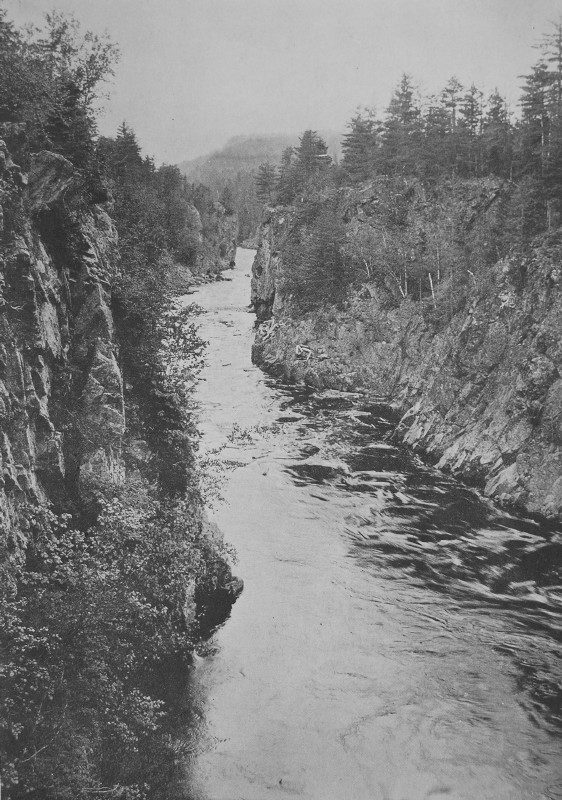

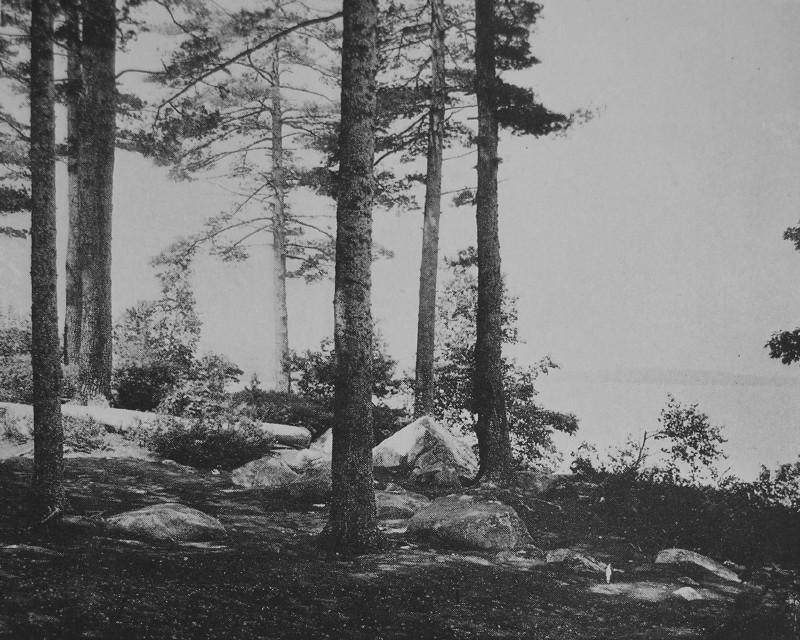

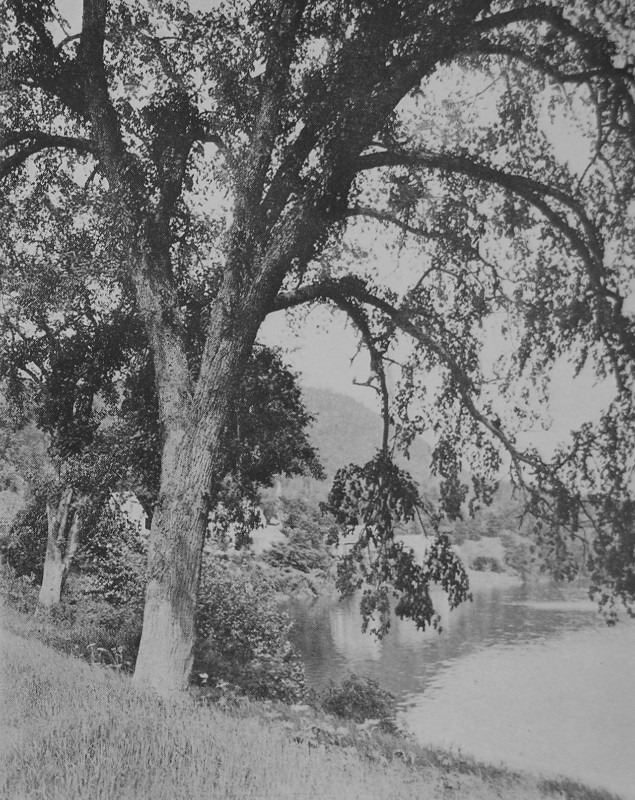

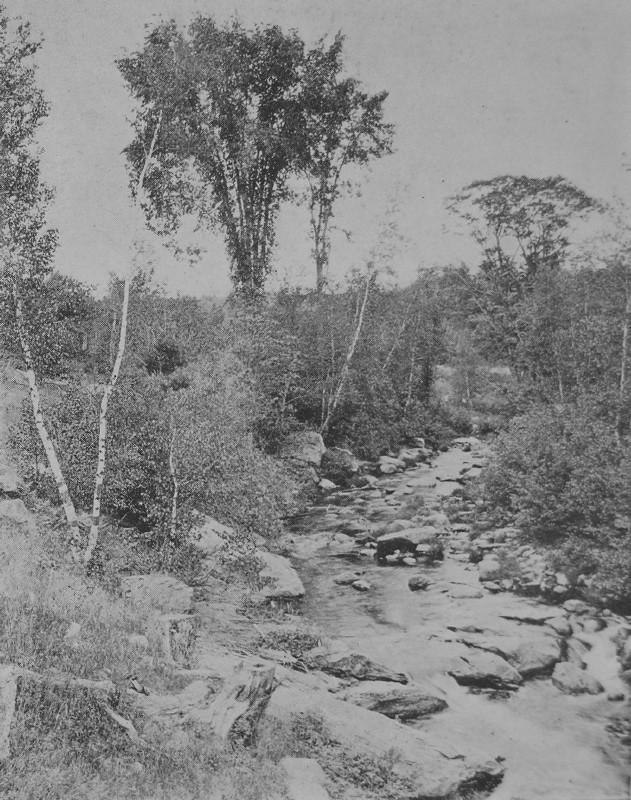

THE good man who lived here (p. 89) has long since gone to care for other sheep. He was mild in his manner and cheerful in his labor. At the country church there was many a one who was called in the language of the town "a hard case." That meant whatever particular sin the person was addicted to, he had not hitherto been weaned from it. It was a matter of dishonest bargaining, or too frequent trips after the "mail." Or perhaps it was too great fondness for hard cider. How difficult it was to hold the people of the countryside to a standard of six days. good work and one day's rest. There was one farmer, who would work seven days. Most of the others could hardly be induced to work six. Sermons on the vineyard and the sower were common. Many a broad hint was dropped by the honest preacher on the matter of stewardship. After such occasions he was thought too personal by certain parishioners, whereas the others were rejoiced that he "hewed to the line." The good man was past middle age, else the parish could not have held him. He sawed his own wood, kept his own garden, and pruned his own trees that we see here. It was the proper thing to have the minister for supper. We do not mean we ate him but ate with him. On the occasion of a clerical visit it was agreed between two neighbors as follows: "You eat him and I'll sleep him." At the ministerial supper the meats were followed by a superabundance of dessert. In addition to a suet or plum pudding there was squash pie, and to crown all, mince pie and strawberry preserves. Any meal at which this honored guest was present would have been thought marked by heresy without the last two named dishes. The farmers were uniformally respectful to the guest, however little they followed his precepts. They knew that he lived the life he professed. WELCOME HOME IN our picture with this title (p. 177) stands the old collie, hopeful and faithful. The cottage with its twin trees is a little one, but it is fairly set and has that rare grace in country cottages, a generous distance from the high road, it being approached by its own private way. Such a situation creates a little kingdom for the happy inhabitant. The owner in this case is a blacksmith, who has thriven and maintained his home far from any large market. Washington is a purely rural town. It is just such a town, however, that simple people of moderate property should seek. It gives an opportunity to purchase a country place of ample size. It is so pleasant to have all the components of a small farm, pasture, woodlot, and fields. Only today we read that the population of Holland is very much crowded, but our immigration laws have made it impossible for the Hollander to find an adequate outlet in America for his diligence and skill. We face the question of inducing our own people to use such good lands as are to be found in Washington and other towns of its type, or to allow the European to do it. Perhaps the recent laws to restrict immigration so rigorously are the first instance in human history of this sort. It raises a strong presumption against any law that no other nation has ever found use for it. It is popular with some trades to keep immigration down. Is there any trade that would not be benefited by a large influx of farmers into America? It is idle to say that there is already more produce raised than can be marketed. The products of staples for export in America are not increasing in quantity. We shall not be happy until in such states as Maine we see all the good farms supplied with good farmers. Not in recent times has there been such an opening. Land is ready cleared and largely fenced and buildings are provided, and at a cost far less than the edifices themselves would require for present construction. There is something wrong in politics, or some defect in the diffusion of knowledge when a good farm goes untilled. We have already mentioned that the orchards are neglected. Their neglect is more obvious than the neglect to land. There is a broad extent of acres in Maine capable of producing a better living than is available to millions of Europeans, in their own country.  A DAISY SHORE - MOUNT DESERT  SEAMED ROCKS - ISLES OF SHOALS  A SEBAGO CURVE  WEST BRANCH, PENOBSCOT  SEBAGO BANKS  TOWARD THE LAKE - NEWPORT We suggest that a

modification of the immigration laws to permit a state to solicit in Europe and

receive on its acres approved farmer proprietors would be an advantage to all

parties concerned. There are various articles on which there is not an over

production on the farm. The case is not

fully met by real-estate agencies that are successful in inducing city people

to invest in farms as summer residences. The value to a state of a non-resident

owner is open to question. we think that here and now it is better that the

farm should be owned by a non-resident who is interested in it than that it

should be in the hands of neglectful owners, whether they dwell on it or have

removed from it. We could wander for years over starved fields which are

neither encouraged to produce wood nor used as pasture or any other purpose. If

a new proprietor expends money in an effort to restore such fields, he helps

the state directly, and indirectly by employing labor. Of course the most

valuable citizen is a resident owner, such as is common in Pennsylvania, where

an intense pride in a farm and a sense of debt to the land is a characteristic

feature. Can the state do anything to induce a love for the land and an

interest in keeping up the farm homesteads? We think that a series of pictures

of the before and after sort, published in the various local papers would be

beneficial. A neglected homestead is first to be shown, then a picture of the

same homestead restored to good condition and a certain degree of beauty. Local

publications could probably do a good deal by illustrating ideal farm houses.

Thus the exotic types not adapted for a Maine climate such for instance as the

bungalow, could be shown to be wrong. The simpler earlier homesteads could be

taken as types. Farmers could be shown by illustration and by detailed methods

how to render brick and stone walls impervious to moisture, and so desirable as

residences. This is important because stone is often available where lumber

must be drawn. The use of pictures

in newspapers is very much neglected as a feature of interest. The cost of

paper suitable to produce half-tones is prohibitory. The only resources is line

drawings. If these could be used by syndicates of country papers their cost would

be negligible. The danger to be

apprehended in such an attempt is the employment of a theoretical architect. He

is sure to attach something to his buildings that adds neither to their use or

beauty. The basis of the work should be good old farm houses and barns which

have long been in the hands of successful farmers. There are many things

attractive to the eye which no farmer can afford to erect, if he must gain the

wherewithal from the soil. About the first thing an architect would suggest is

a great quantity of stone fence laid in mortar. This is almost always a total

waste. The same construction in house walls would be sensible. A consideration

often forgotten is the climate in which the erection is to be made. What is

suitable for Pennsylvania would not be wise in Maine. An important

question to ask of any construction is, how long will it last without repairs?

The cost of paint is prohibitory. A farmer has an obsession in favor of paint,

or at least his wife has. Natural wood seems an abomination in their eyes.

Nevertheless, it is beautiful especially as an interior finish, and requires

slight attention. Out-of-doors, masonry walls could be encouraged more and

more, on the score of durability and availability. Any farmer can do what

pointing is necessary on such walls, and can do it in weather when painting

would not be possible. Also he can use materials of very small cost. A definite search

for the proper farm buildings would easily result in an abundance of material

for illustration. We see, in journeying through the country, repairs or

additions being made to very many farm houses. As often as otherwise the

additions are made rather to be in fashion than to be useful, and the repairs

are of such a character that they will have to be done over in a brief time. The passion for

newness, aside from any merit connected therewith, is the cause of a vast

amount of wrongly directed expense. If the money wasted in repairs in Maine

were expended in accordance with the wisdom of experience the state could almost

be built over in a generation. It would be easy

for a state to provide through its agencies already established, competent

advice as to style and fitness of edifices. It would be a far more sensible act

than that of giving out seeds gratis. It is true that many trained men are

trained in a one-sided manner so that the selection of such men should be based

on most practical considerations. If a sufficient

body of material such as we have suggested were published from week to week and

year to year, the rural districts of Maine would be educated in the best forms

and materials for their use. The present obstacle is the lack of good examples

and the abundance of horrible examples. By this we mean that the city house

erected in the country is perhaps the last thing that the farmer needs. If a love for the

preservation of the old could be inculcated, the task would be half done. Good

houses are continually being abandoned because they are old and new dwellings

erected. It is to the interest of the carpenter, or at least so he conceives

it, to erect new structures. Carpenters dislike working with old materials. A

farmer will sometimes say that it would cost him almost as much to repair as to

build new. Even so, if he repairs properly, he may have something of large

value to show for his labor. But if he builds it is quite likely that his

children will be ashamed of what he has produced, because good taste today in

building is not as common as it was a hundred years ago. Farm buildings

should either be well kept up or torn down. Modern costs of foundations are so

great that more and more the scale turns in favor of repairs rather than new

construction. We would almost hazard the statement that the lines of a

substantial farm house built before 1820 can seldom be improved. The addition

of a bath-room, by the appropriation of a chamber which the modern small family

does not need, and the installation of a central heating system, are needed and

are the only features in construction which the nineteenth century has produced

of any importance. Of course, modern lighting is taken for granted. As the pictures of improved dwellings, sedulously published, would be of importance, so also would illustrations of neglected fruit trees compared with carefully tended trees be of use. Perhaps garden pictures would not be sufficiently clear to be worth while. The training of vines and flowers about the dwelling, and the setting of such a dwelling amid shrubs and trees, could be very well illustrated. OLD DWELLINGS IN

MAINE WE have stated that

the proportion of such old dwellings is very much smaller in Maine than in the

southern New England states. Maine is a new country except for its shore and

lower river districts. The one-story dwelling with one chimney, a square front

entry, and a room on each side, is the typical old house of Maine, just as it

is of the rest of the New England states. The roof has a good pitch, and the

chimney is large unless it is modern. In the course of improvements a one- or

even two-story ell has been added. This house may date in the eighteenth or

early nineteenth century. It never had any porch, nor was there an overhang

roof. The glass in the windows was always small, probably never larger than

eight by ten inches, and usually less than that size. The original boards of

the floors were of wide pine, sometimes yellow, sometimes white. There was a

fire-place in each of the rooms. Sometimes there was a small fire-place in the

attic rooms in case the attic was divided. Despite the simplicity of such a dwelling,

it has a strong attraction. It is so obviously built to fit a need, and so

perfectly represents the early life of the settlers that we find it most

satisfactory. Of the earliest period of architecture there are very few

examples beyond what we have mentioned. Every one of the ancient houses of

Pemaquid has vanished. Even the block-house of stone has been largely

reconstructed, and the other blockhouses date in the eighteenth rather than in

the seventeenth century. The old house in

Maine, as the Maine man thinks of it, is the eight room dwelling with four

chimneys, two in each side wall, which came into fashion at the time of the

Revolution and continued to about 1820. You will find an example of such a

house as we show at Wiscasset. All the coast towns have similar dwellings. They

sometimes rise into a third story, although that construction is a little late

and is not likely to be so good in style. At the time of the Revolution, the

interior of these dwellings was carefully done with a good deal of panel work

about fire-places and stairways, and with large and excellent cornices of wood.

There was a rapid declension after 1790, and about 1810 we find the rooms very

boxy, without cornice, without dado, and with somewhat plainer fire-places.

There was also a rapid declension in the style of the iron work. Latches in the

later time were made of plates struck out on a die cutter. Wrought work

disappeared. Modern butts superseded the large, visible hinges of the doors. Nearly

all the ornament on houses after 1800 was on the outside. There the decoration

was not seldom ornate. One sees an edifice of this sort and thinks of it as a

very fine dwelling. As soon, however, as he steps over the threshold he finds

that the interior construction is as bare as a barn. Seekers for old houses

should carefully observe these indications of declension in style, and so avoid

a rude awakening. There are thousands of people today who are scurrying about

trying to buy old paneling to make their old houses older. For the most part

their search is vain. Such items as these are now held at fancy prices. The

buyer of an old house in Maine is, however, likely to get what he wants, if he

knows what that is. The style of house we are now describing is not uncommon.

If the edifice had brick sides or ends the chimneys would not require to be

built over, but at least that chimney which is to be used for heating should be

carefully examined. A feature to be avoided is a roof of low pitch. Constant

leaks and constant renewals go with such inadequately pitched roofs. If the

searchers can find a dwelling erected before the Revolution, the roof is

usually of sufficiently high pitch. We would strongly advise against the

improvement of any old house so as to spoil its style. It has a genius of its

own, and should be kept to its original scheme or the result is a very

unsatisfactory mongrel. The charm is entirely lost by dragging in some feature

inconsistent with the original design, and bearing no relation to other parts

of the house. Such houses as we

have mentioned may be found along the banks of all the navigable streams and in

all the coast towns and on most of the roads that date back to the period

concerned. Dwellings of the sort we are describing are always airy, ample in size, and require no additions. Their four chambers supply as much room as is required because the hall bedroom may be taken for a bath-room. If other bath-rooms are desired, there is often a dressing-room between the two side-rooms which can be utilized. One other improvement may often be added to advantage, and that is a dignified cornice of wood about the rooms. It is probably best to stop with the improvements outlined. The advantage of adding paneling scarcely justifies the pains and the other changes required. VINE CORNICE, NEW VINYARD If one contents

himself with the dwellings of the revived Gothic period of 1830, it is best to

leave them as we find them except for plumbing and heating. These dwellings are

not as bad as they are painted. The chief objection to them is the high

ceiling, but this is not felt in the summer except as a merit. Of course they

are without the touch of good artisans, but that is to be expected in the

nineteenth century. One could hardly commit a more depressing error than to try

to change the style of one of these houses to the period of fifty or sixty

years before. Should he unfortunately start on this crusade he would find

himself spending more than would be required for just such an old house as he

is imitating. One little detail,

which nevertheless is very apparent as we approach a dwelling, is the woodshed.

The old flat arches ought to be built or restored, and the wood-pile neatly

laid up with sawed ends outward. No other expenditure can afford so much

pleasure in the quaint and the practical. It is very common

to find the old barn on the side of the road opposite the house and in a direct

line with the best view. In that case it is wise to demolish the old structure

and to provide such a barn as may be needed a good distance from the dwelling,

and in a location that cannot be criticized. With the fluctuations of human affairs it is hardly likely that the present condition will continue, by which good old places with farms attached may be purchased in Maine for low prices. We have a growing population, and the attractive portions of the country have been covered by their first settlements. It is now time to go over the ground for a second inspection, and to learn what good things have been left behind by the western urge. It is difficult to predict when the resurge of populations will occur. It is perfectly certain, however, that some time, and probably not many years hence, it will be felt that the best opportunities are in the east. We ought to pick the berries that are nearest us. Perhaps those beyond are culled or sour. Probably not in modern times have country opportunities, equal to the present, existed.  PATTEN BROOK - SURRY  A VILLAGE ELM - RUMFORD CENTRE  A BANK OF MOSS - SOMERSET COUNTY  A MAINE BROOK  A WAITING RIVER - WEBB RIVER  UNION RIVER  BY THE RANGELEY ROAD WELLS AND SPRINGS

IN a country so

rich in waters as is Maine, it is difficult to picture the importance attached

in arid lands to wells and springs. Perhaps the first human construction of an

engineering sort, after the irrigation of the cradles of the race, was the

digging of wells. The ownership of a well was better than that of a mine.

Battles for possession are among the earliest tales of history. The love-making

of Moses and Jacob was centered about wells. The greatest sermon ever delivered

had the well by which the preacher stood as a text. In western Europe the

stream was too often made to do duty instead of wells. But where a gushing

natural spring occurred, the spot was ornamented in all ages by temples or

gardens, or at the least by a coping or a receptacle carved with art and

adorned by appropriate inscription. In New England the

town pump was first the village center. As settlers became thrifty,

enterprising, or opulent, they dug each for himself a well. The ancient wells

of Maine are among its most interesting objects. It seems to be the prevailing

impression that the well-sweep is the earliest form. We very much doubt the

correctness of this impression. Certainly in the old world, hundreds of years

before the settlement of America, the windlass well was common. It seems far

more probable that a windlass was in use in America for the most part, from the

earliest times. We think that the well-sweep was a contrivance quickly

adjusted, with the thought, probably, of superseding it by a windlass. In fact,

heretical as it may seem, we think a windlass well, at least if it has a fairly

good canopy, is more picturesque than a well-sweep. The old windlass often had

a balancing stone to counteract the weight of the bucket of water. But the

well-sweep, when situated in a picturesque location (p. 80), backed by apple

blossoms, has its merits. One still finds it, now and again, in Maine.

Sometimes, indeed, the old oaken bucket is replaced by a tin pail. Of course it

is well under: stood that water from a bucket is very much better than from any

other receptacle. We are not, however, among those who consider that a

well-sweep is the only thing required to give an atmosphere of antiquity to a

Maine homestead. If we were to speak

of convenience, and to remain in the realm of the practical, we should find

that the watering of the stock, and the various other calls for watering in quantity,

make it inevitable, on a Maine farm, that some more convenient source of water

supply should be provided. One of the greatest burdens of our grandmothers was

the necessity of pumping water. The writer's own grandmother sustained a

terrible tragedy by the flying up of a pump handle. The burden of bringing the

water, which was often left to the women of the household, was very great. For

this reason, the slopes behind the farm houses were investigated for springs,

and the enterprising farmer has a supply flowing to his buildings by gravity.

More recently the very small charge for electrical power has stimulated the

installation of pumps to bring water up from flowing sources below the

dwellings. In these particulars the Maine farmers indicate their alertness, and

farm life is relieved by this improvement, and finally, by the cream separator,

of its last drudgery. It is curious, in

this connection, how we hark back to our childhood, even to those features

which emphasize the toil and burden of that day. It is only necessary to think

of the things that are done easily today, to perceive in a moment how complete

the change has been. All the heavy work on the farm is or may be done in our

day by power. It was amazing and in some degree amusing to see, on a recent

visit to Maine, the more conservative farmers engaged in the manipulation of

the buttons and the valves which let loose the powers of electricity or

gasoline to do their work. This is one of the alleviating aspects of the labor

question. we are acquainted with one farmer in Maine who has dispensed with the

work of two men by employing power which he can pay for, through a week, for

the cost of one day's labor. |