Rolandseck

Knight

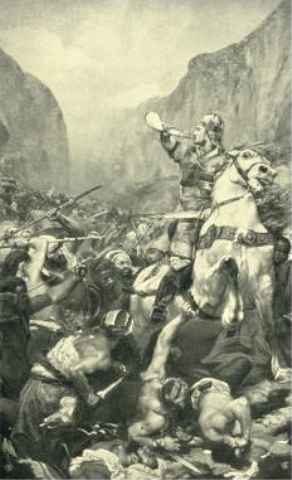

Roland

Roland

in der Schlacht von Roncevalles

Nach dem Gemalde von A. Guesnet

I.

The Emperor Charlemagne was surrounded by a circle

of

proud knights, the flower of whom was Count Roland of Angers, nephew of

the

King of the Franks. The name of no knight was so famous in battle and

in

tournaments as his.

Helpless innocency adored him, his friends

admired, and

his enemies esteemed him. His chivalrous spirit had no love for the

luxuries

of life, and scorning to remain inactive at the emperor's court, he

went

to his imperial uncle, begging leave to go and travel in those

countries

of the mighty kingdom of the Franks, which up to that time were unknown

to

him. In his youthful fervour he longed for adventures and dangers. The

emperor

was much grieved to part with the brave knight, but however, he

willingly

complied with his request.

One day early in the morning the gallant hero left

his

uncle's palace near the Seine, and rode towards the Vosges Mountains,

accompanied

by his faithful squire. The first object of his journey was castle

Niedeck

near Haslach, and from there he visited Attic, Duke of Alsace.

He continued his travels, and one evening as he was riding

through the mountains, the glittering waters of the Rhine, washing both

sides

of the plain, greeted him. The river in that part of the country

offered

him few charms in its savage wildness, but he knew that the scenery

would

soon change. He moved on down the Rhine to where a gigantic mountain

shuts

the rushing current into a narrow space. Its foot stands chained in the

floods,

which only in places retire a little, thus leaving the poor folk a

narrow

stretch of land.

On the heights there were proud castles, telling

the

wanderer below of the fame of their illustrious races. Thus Roland made

many

a long journey on his adventurous course down the Rhine. He passed many

a

place rich in old memories: the Lorelei Rock, where the water nymph

sang

at night: the cheerful little spot where St. Goar lived and worked at

the

time of Childebert, the Merovingian, (that wonderful saint who once

spread

a fog over his imperial uncle, compelling him to pass the night in the

open

air, because his Majesty, while journeying from Ingelheim to Coblenz

had

neglected to bend his knee in his chapel) and the green meadows near

Andernach,

where Genovefa, wife of Palatine Count Siegfried lived. And now Roland

neared

the place where the stream reaches the end of the Rhine Valley, and

where

the seven giants are to be seen, the summit of one of which is crowned

with

a castle; there they stand like the seven knights who, in later times

stood

weeping round the holy remains of the German emperor.

A wooded island lay in the deep-blue waters. The

setting

sun threw a golden light over the hills. On the sides of the mountains

there

were numberless vineyards, to the left, hedges of beeches ascending to

the

heights of the rugged summits, to the right, the murmur of the rippling

waters,

and above, visible among the legendary rocks where once a terrible

beast

lived, the pinnacles of a knight's castle, and over all, the heavens

clothed

with a garment of silver stars.

The knight paused in silence; his glance rested

admiringly

on the beautiful picture. His steed pawed the ground uneasily with his

bronze-shod hoofs, and his faithful squire looked anxiously at the

darkening

sky. He reminded his master modestly that it was time to seek shelter

for

the night.

"I should like to beg for it up there," said

Roland

dreamingly, an inexplicable feeling of sweet sadness coming over him

for

the first time. He bade his squire ask the boat-man who was putting out

his

little bark to cross the river, what was the name of the castle? The

castle

was the Drachenburg, where Count Heribert sojourned sometimes. Thus ran

the

answer which pleased Roland very much. He had been charged with many

greetings

and messages to the old count at the Drachenburg from his friends

living

near the upper Rhine. Roland now hesitated no longer, and soon a boat

was

ploughing the dark waves.

II.

In the meantime night had come on. The full moon's

soft

beams showed them their way through the dark forest. Count Heribert, a

worthy

knight in the flower of his age, bade the nephew of his imperial master

heartily

welcome to his castle. Far past midnight they stayed in the count's

chambers,

engaged in entertaining conversation.

The next day Count Heribert presented his daughter

Hildegunde

to the knight. Roland's eves. full of admiration, rested on the

blushing

young maiden. Never before had the charms of a woman awakened any deep

feeling

in his heart; he had only thirsted after glory and deeds of daring,

after

tournaments and feuds. Now the bold champion was struck with a shaft

from

the quiver of love. He who had opposed the dreaded adversary so often,

now

bowed his fearless head in almost girlish confusion before Hildegunde's

charms.

She, too, stood crimsoning deeply before the celebrated hero whose name

was

famous, and who was beloved in all the country round.

The old knight broke up the scene of embarrassing

silence

between the youthful couple with gay laughing words, and conducted his

guest

through the high halls of his castle.

Roland tarried longer at the friendly castle than he had

ever

done before in any other place in the country. He seemed bound to the

blissful

spot by love's indissoluble chains, and so it happened that one day

these

two found themselves, hand in hand, the deep love in their hearts

rushing

forth in ardent words. Count Heribert bestowed his lovely daughter very

willingly

on the celebrated knight, his only desire being to complete the

happiness

of his child whom he loved so dearly. A castle should be erected for

her

on the heights of the rocks on the other side of the Rhine, opposite

the

Drachenburg, and this proud tort on the rugged rocky corner of the

mountain,

should be a watch-tower for the glorious Seven Mountains and their

castle.

In later times it became the famous Rolandseck. Soon the walls could be

seen

raising themselves up, and every day the lovers stood On the balcony of

the

Drachenburg looking across, where industrious workmen and masons were

busily

toiling. Hildegunde began to weave sweet dreams of the future round her

new

home, where she meant to chain the adventurous hero with true love.

But one day a messenger appeared at the

Drachenburg on

a horse white with foam. He was sent by Charlemagne and brought the

tidings

.of a crusade which the .emperor had decreed against the Infidels

beyond

the Pyrenees. Charlemagne desired to have the famous knight among the

leaders

of his army. Roland received the message of his great master in

silence.

He looked at Hildegunde who with a death-like face was standing beside

him.

Grief stabbed cruelly at his heart, but he must obey the call of honour

and

duty, and, informing the royal messenger that he would arrive at the

imperial

camp in three days, he turned sorrowfully away, Hildegunde sobbing at

his

side.

III.

The cross and the crescent were fighting furiously

for

the upper hand in Spain. Terrible battles were fought, and much blood

flowed

from both Christians and Infidels. Bloody victories were gained by the

emperor's

brave knights, the chief .of whom was Roland. His sword forced a

triumphant

way for Charlemagne, it guarded his army, passing victoriously through

the

unknown country of the enemies. But the sad day of Ronceval, so often

sung

by German and other poets was yet to come. Separated from the main body

of

the army, Roland's brave rearguard was making its way through the dusky

forest.

Suddenly wild shouts sounded from the heights, and the cowardly Moor

pressed

down on the little band, threatening them with destruction. But the

noble

Franks fought like lions. Roland's charger, Brilliador, flew now here,

now

there, and many a Saracen was hewn down by its noble rider's sword,

Durand.

But numbers conquer bravery. The little army of Franks became less and

less,

and at last Roland sank, struck by the lance of a gigantic Moor. The

combat

continued furiously round him. When night spread mournfully over the

battle-field, the Infidels had already done their terrible work. The

Franks

lay dead; only a few had escaped from the slaughter.

"Where is Roland?" was the frightened cry from

pale

lips. He was not among the saved. "Where is Roland?" asked Charlemagne

anxiously

of the messengers. Through the whole kingdom their answers seemed to

resound,

Roland the hero had fallen in battle fighting against the Saracens;

wherever

this cry was heard, it awakened deep sorrow.

The news soon spread as far as the Rhine, and one

day

the imperial messengers appeared at the Drachenburg, bringing the sad

tidings

and the deepest sympathy of the emperor. Heribert sighed deeply on

hearing

the news and covered his eyes with his hands; Hildegunde's grief was

heart-breaking. Before the altar of the Queen of sorrows she lay

sobbing

her heart out, imploring for comfort in her great need. For days on end

she shut herself up in her little bower, and even her father's gentle

sympathy

could not assuage her bitter grief.

Weeks passed. Then one day the pale maiden

.entered the

knight's chamber, her grief quite transfigured. He drew her softly

towards

him, and then she revealed the resolution which was in her heart. Count

Heribert

was overwhelmed with grief, but he pressed a loving kiss on her pure

forehead.

The day came, when down below on the island Nonnenwert, the

convent bells rang solemnly. A new novice, Count Heribert's lovely

daughter,

knelt before the altar. In the holy stillness of the convent she sought

the

peace which she could not find in the castle of her father. With a last

great

convulsive sob she had torn her lover's name from her heart, had

quenched

the flame of sorrowing love for him, and now her soul was to be filled

ever

with the holy fire of the love of God. In vain her afflicted father

hoped

that the unaccustomed loneliness of the convent would shake her

resolution,

and that when the first year's trial was over, she would return to him.

But

no! the pious young maiden fervently begged the bishop, who was a

relation

of her father, to release her from the year's trial and to allow her

after

a short time to take her final vows. Her longing desire was fulfilled.

After

a month Hildegunde's golden locks were no more, and the lovely daughter

of

the Drachenburg was dedicated to the Lord forever.

IV.

Time rolled on. Spring had vanished and the

sheaves were

ripening in the fields. Where the river reaches the end of the Rhine

valley

crowned by the Seven Giants, a knight with his horse stopped to rest.

Far

away in the south, where the valley of Ronceval lies bathed in

sunshine,

he had lain in the hut of a poor herd. There the faithful squire had

dragged

his master pierced by a Moorish lance. The bold hero and leader had

remained

for weeks and months on his sick-bed struggling with death, till the

force

of his iron nature had at last conquered. Roland was recovering under

loving

care, while they were mourning him as dead in the land of the Franks.

Then

having recovered, he hurried back to the Rhine urged by an irresistible

longing.

A wooded island lay in the deep-blue waters. The

setting

sun threw a golden light over the hills; numberless vineyards flanked

the

mountains, hedges of beeches were on one side, the murmur of waters on

the

other, and above the pinnacles of a knight's castle among the legendary

rocks

where once a terrible beast lived, over all the heavens clothed with a

garment

of silver stars.

Silently the knight paused, his glance resting

admiringly

on the beautiful picture. Now as in months before an inexplicable

feeling

of sweet sadness came over the dreamer.

"Hildegunde!" murmured Roland, glancing up at the

starry

heavens. Again as formerly a boat-man rowed across the stream, and

Roland

soon was striding through the forest towards the Drachenburg,

accompanied

by his faithful squire.

The old watchman at the castle stared at the late

guest,

and crossing himself, he rushed up to the chambers of his master. A

man's

figure, bent with age and sorrow, tottered forward. "Roland!" he gasped

forth.

The knight supported the broken-down old man in his arms. When Roland

had

departed long ago, his grief had found no tears; now they flowed

abundantly

down his cheeks.

The knight tore himself from the other's arms.

"Where is she?" he asked in a hoarse voice,

"dead?"

Count Heribert looked at him with unspeakable

sorrow.

"Hildegunde, bride of Roland whom they supposed dead, is now a bride of

Heaven."

The hero groaned aloud, covering his face with his

hands.

In spring he left the Drachenburg and went to the

castle

on the rocky corner, and there he laid down his arms for ever; his

thirst

for action was quenched. Day by day he sat over there, looking silently

down

on the green island in the Rhine, where the nun, Hildegunde, wandered

about

among the flowers in the convent garden every morning. Sometimes indeed

it

seemed that she bowed kindly to him, then the knight's face would be

lighted

up with a gleam of his old happiness.

But even this joy was taken from him, One day his

beloved

did not appear; and soon the death-bell tolled sorrowfully over the

island.

He saw a coffin which they were carrying to its last resting-place, and

he

heard the nuns chanting the service for the dead, he saw them all, only

one

was wanting . . . then he covered his face. He knew whom they were

carrying

to the grave.

Autumn came, withering the fresh green on

Hildegunde's

tomb. But Roland still kept his watch, gazing motionlessly at the

little

churchyard, and one day his squire found him there, cold and dead, his

half-closed eyes turned towards the place where his loved one was

sleeping.

For many a century the proud castle which they

called

Rolandseck, crowned the mountain. Then it fell into ruins, like the

mighty

Drachenburg, the tower of which is still standing. Fifty years ago the

last

arches of Roland's castle were blown down one stormy night, but later

on

they were built up again in memory of this tale of true and faithful

love

in the olden times.

Click

to go to the next

section of

the Legends of the Rhine to go to the next

section of

the Legends of the Rhine

|