|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XVIII THE ORIGIN OF MACHU PICCHU SOME other day I hope

to tell

of the work of

clearing and excavating Machu Picchu, of the life lived by its

citizens, and of

the ancient towns of which it was the most important. At present I must

rest

content with a discussion of its probable identity. Here was a powerful

citadel

tenable against all odds, a stronghold where a mere handful of

defenders could

prevent a great army from taking the place by assault. Why should any

one have

desired to be so secure from capture as to have built a fortress in

such an

inaccessible place? The builders were not

in search

of fields. There is

so little arable land here that every square yard of earth had to be

terraced

in order to provide food for the inhabitants. They were not looking for

comfort

or convenience. Safety was their primary consideration. They were

sufficiently

civilized to practice intensive agriculture, sufficiently skillful to

equal the

best masonry the world has ever seen, sufficiently ingenious to make

delicate

bronzes, and sufficiently advanced in art to realize the beauty of

simplicity.

What could have induced such a people to select this remote fastness of

the

Andes, with all its disadvantages, as the site for their capital,

unless they

were fleeing from powerful enemies. The

thought will

already have occurred to the reader that the Temple of the Three

Windows at

Machu Picchu fits the words of that native writer who had “heard from a

child

the most ancient traditions and histories,” including the story already

quoted

from Sir Clements Markham’s translation that Manco Ccapac, the first

Inca,

“ordered works to be executed at the place of his birth; consisting of

a

masonry wall with three windows, which were emblems of the house of his

fathers

whence he descended. The first window was called ‘Tampu-tocco.’”

Although none

of the other chroniclers gives the story of the first Inca ordering a

memorial

wall to be built at the place of his birth, they nearly all tell of his

having

come from a place called Tampu-tocco, “an inn or country place

remarkable for

its windows.” Sir Clements Markham, in his “Incas of Peru,” refers to

Tampu-tocco as “the hill with the three openings or windows.” The place

assigned by all the

chroniclers as the location of the traditional Tampu-tocco, as has been

said, is

Paccaritampu, about nine miles southwest of Cuzco. Paccaritampu has

some

interesting ruins and caves, but careful examination shows that while

there are

more than three openings to its caves, there are no windows in its

buildings.

The buildings of Machu Picchu, on the other hand, have far more windows

than

any other important ruin in Peru. The climate of Paccaritampu, like

that of

most places in the highlands, is too severe to invite or encourage the

use of

windows. The climate of Machu Picchu is mild, consequently the use of

windows

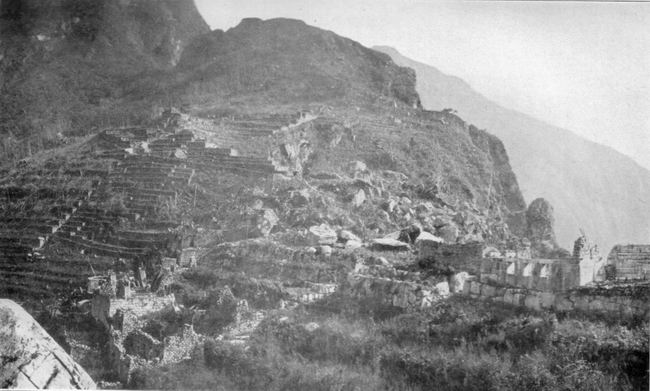

was natural and agreeable. So far as I know, there is no place in Peru where the ruins consist of anything like a “masonry wall with three windows” of such a ceremonial character as is here referred to, except at Machu Picchu. It would certainly seem as though the Temple of the Three Windows, the most significant structure within the citadel, is the building referred to by Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamayhua.  THE MASONRY WALL WITH THREE WINDOWS, MACHU PICCHU The principal

difficulty with

this theory is that

while the first meaning of tocco in

Holguin’s standard Quichua dictionary is

“ventana” or “window,” and while “window” is the only

meaning given this important word

in Markham’s revised Quichua

dictionary (1908), a dictionary compiled from many sources, the second

meaning

of tocco given by Holguin is “alacena,” “a

cupboard set in a wall.”

Undoubtedly this means what we call, in the ruins of the houses of the

Incas, a

niche. Now the drawings, crude as they are, in Sir Clements Markham’s

translation of the Salcamayhua manuscript, do give the impression of

niches

rather than of windows. Does Tampu-tocco mean

a tampu remarkable for its niches?

At

Paccaritampu there do not appear to be any particularly fine niches;

while at

Machu Picchu, on the other hand, there are many very beautiful niches,

especially in the cave which has been referred to as a “Royal

Mausoleum.” As a

matter of fact, nearly all the finest ruins of the Incas have excellent

niches.

Since niches were so common a feature of Inca architecture, the chances

are

that Sir Clements is right in translating Salcamayhua as he did and in

calling

Tampu-tocco “the hill with the three openings or windows.” In any case

Machu

Picchu fits the story far better than does Paccari-tampu. However, in

view of

the fact that the early writers all repeat the story that Tampu-tocco

was at

Paccaritampu, it would be absurd to say that they did not know what

they were

talking about, even though the actual remains at or near Paccari-tampu

do not

fit the requirements. It would be easier to

adopt

Paccaritampu as the site

of Tampu-tocco were it not for the legal records of an inquiry made by

Toledo

at the time when he put the last Inca to death. Fifteen Indians,

descended from

those who used to live near Las Salinas, the

important salt works near

Cuzco, on being questioned, agreed that they had heard their fathers

and

grandfathers repeat the tradition that when the first Inca, Manco

Ccapac,

captured their lands, he came from Tampu-tocco. They did not say that

the first

Inca came from Paccaritampu, which, it seems to me, would have been a

most

natural thing for them to have said if this were the general belief of

the

natives. In addition there is the still older testimony of some Indians

born

before the arrival of the first Spaniards, who were examined at a legal

investigation in 1570. A chief, aged ninety-two, testified that Manco

Ccapac

came out of a cave called Tocco, and that he was lord of the town near

that

cave. Not one of the witnesses stated that Manco Ccapac came from

Paccaritampu,

although it is difficult to imagine why they should not have done so

if, as the

contemporary historians believed, this was really the original

Tampu-tocco. The

chroniclers were willing enough to accept the interesting cave near

Paccaritampu as the place where Manco Ccapac was born, and from which

he came

to conquer Cuzco. Why were the sworn witnesses so reticent? It seems

hardly

possible that they should have forgotten where Tampu-tocco was supposed

to have

been. Was their reticence due to the fact that its actual whereabouts

had been

successfully kept secret? Manco Ccapac’s home was that Tampu-tocco to

which the

followers of Pachacuti VI fled with his body after the overthrow of the

old

regime, a very secluded and holy place. Did they know it was in the

same

fastnesses of the Andes to which in the days of Pizarro the young Inca

Manco

had fled from Cuzco? Was this the cause of their reticence? Certainly the

requirements of

Tampu-tocco are met at

Machu Picchu. The splendid natural defenses of the Grand Canyon of the

Urubamba

made it an ideal refuge for the descendants of the Amautas during the

centuries

of lawlessness and confusion which succeeded the barbarian invasions

from the

plains to the east and south. The scarcity of violent earthquakes and

also its

healthfulness, both marked characteristics of Tampu-tocco, are met at

Machu

Picchu. It is worth noting that the existence of Machu Picchu might

easily have

been concealed from the common people. At the time of the Spanish

Conquest its

location might have been known only to the Inca and his priests. So, notwithstanding

the belief

of the historians, I

feel it is reasonable to conclude that the first name of the ruins at

Machu

Picchu was Tampu-tocco. Here Pachacuti VI was buried; here was the

capital of

the little kingdom where during the centuries between the Amautas and

the Incas

there was kept alive the wisdom, skill, and best traditions of the

ancient folk

who had developed the civilization of Peru. It is well to

remember that the

defenses of Cuzco

were of little avail before the onslaught of the warlike invaders. The

great

organization of farmers and masons, so successful in its ability to

perform

mighty feats of engineering with primitive tools of wood, stone, and

bronze,

had crumbled away before the attacks of savage hordes who knew little

of the

arts of peace. The defeated leaders had to choose a region where they

might

live in safety from their fierce enemies. Furthermore, in the environs

of Machu

Picchu they found every variety of climate — valleys so low as to

produce the precious

coca, yucca, and

plantain, the fruits and

vegetables of

the tropics; slopes high enough to be suitable for many varieties of

maize, quinoa, and other cereals,

as well as

their favorite root crops, including both sweet and white potatoes, oca,

aņu, and ullucu. Here,

within a few hours’ journey, they could

find days warm enough to dry and cure the coca

leaves; nights cold

enough to freeze potatoes in the approved aboriginal fashion. Although the amount

of arable

land which could be

made available with the most careful terracing was not large enough to

support

a very great population, Machu Picchu offered an impregnable citadel to

the

chiefs and priests and their handful of followers who were obliged to

flee from

the rich plains near Cuzco and the broad, pleasant valley of Yucay.

Only dire

necessity and terror could have forced a people which had reached such

a stage

in engineering, architecture, and agriculture, to leave hospitable

valleys and

tablelands for rugged canyons. Certainly there is no part of the Andes

less

fitted by nature to meet the requirements of an agricultural folk,

unless their

chief need was a safe refuge and retreat. Here the wise remnant

of the

Amautas ultimately

developed great ability. In the face of tremendous natural obstacles

they

utilized their ancient craft to wrest a living from the soil. Hemmed in

between

the savages of the Amazon jungles below and their enemies on the

plateau above,

they must have carried on border warfare for generations. Aided by the

temperate climate in which they lived, and the ability to secure a wide

variety

of food within a few hours’ climb up or down from their towns and

cities, they

became a hardy, vigorous tribe which in the course of time burst its

boundaries, fought its way back to the rich Cuzco Valley, overthrew the

descendants of the ancient invaders and established, with Cuzco as a

capital,

the Empire of the Incas. After the first Inca,

Manco

Ccapac, had established

himself in Cuzco, what more natural than that he should have built a

fine temple

in honor of his ancestors. Ancestor worship was common to the Incas,

and

nothing would have been more reasonable than the construction of the

Temple of

the Three Windows. As the Incas grew in power and extended their rule

over the

ancient empire of the Cuzco Amautas from whom they traced their

descent,

superstitious regard would have led them to establish their chief

temples and

palaces in the city of Cuzco itself. There was no longer any necessity

to

maintain the citadel of Tampu-tocco. It was probably deserted, while

Cuzco grew

and the Inca Empire flourished. As the Incas

increased in power

they invented

various myths to account for their origin. One of these traced their

ancestry

to the islands of Lake Titicaca. Finally the very location of Manco

Ccapac’s

birthplace was forgotten by the common people-although undoubtedly

known to the

priests and those who preserved the most sacred secrets of the Incas. Then came Pizarro and

the

bigoted conquistadores. The native

chiefs faced

the necessity of saving whatever was possible of the ancient religion.

The

Spaniards coveted gold and silver. The most precious possessions of the

Incas,

however, were not images and utensils, but the sacred Virgins of the

Sun, who,

like the Vestal Virgins of Rome, were from their earliest childhood

trained to

the service of the great Sun God. Looked at from the standpoint of an

agricultural people who needed the sun to bring their food crops to

fruition

and keep them from hunger, it was of the utmost importance to placate

him with

sacrifices and secure the good effects of his smiling face. If he

delayed his

coming or kept himself hidden behind the clouds, the maize would mildew

and the

ears would not properly ripen. If he did not shine with his accustomed

brightness after the harvest, the ears of corn could not be properly

dried and

kept over to the next year. In short, any unusual behavior on the part

of the

sun meant hunger and famine. Consequently their most beautiful

daughters were

consecrated to his service, as “Virgins” who lived in the temple and

ministered

to the wants of priests and rulers. Human sacrifice had long since been

given

up in Peru and its place taken by the consecration of these damsels.

Some of

the Virgins of the Sun in Cuzco were captured. Others escaped and

accompanied

Manco into the inaccessible canyons of Uilcapampa. It will be remembered

that

Father Calancha relates

the trials of the first two missionaries in this region, who at the

peril of

their lives urged the Inca to let them visit the “University of

Idolatry,” at

“Vilcabamba Viejo,” “the largest city” in the province. Machu Picchu

admirably

answers its requirements. Here it would have been very easy for the

Inca Titu

Cusi to have kept the monks in the vicinity of the Sacred City for

three weeks

without their catching a single glimpse of its unique temples and

remarkable

palaces. It would have been possible for Titu Cusi to bring Friar

Marcos and

Friar Diego to the village of Intihuatana near San Miguel, at the foot

of the

Machu Picchu cliffs. The sugar planters of the lower Urubamba Valley

crossed

the bridge of San Miguel annually for twenty years in blissful

ignorance of

what lay on top of the ridge above them. So the friars might easily

have been

lodged in huts at the foot of the mountain without their being aware of

the

extent and importance of the Inca “university.” Apparently they

returned to

Puquiura with so little knowledge of the architectural character of

“Vilcabamba

Viejo” that no description of it could be given their friends,

eventually to be

reported by Calancha. Furthermore, the difficult journey across country

from

Puquiura might easily have taken “three days.” Finally, it appears

from Dr.

Eaton’s studies that

the last residents of Machu Picchu itself were mostly women. In the

burial

caves which we have found in the region roundabout Machu Picchu the

proportion

of skulls belonging to men is very large. There are many so-called

“trepanned”

skulls. Some of them seem to belong to soldiers injured in war by

having their

skulls crushed in, either with clubs or the favorite sling-stones of

the Incas.

In no case have we found more than twenty-five skulls without

encountering some

“trepanned” specimens among them. In striking contrast is the result of

the

excavations at Machu Picchu, where one hundred sixty-four skulls were

found in

the burial caves, yet not one had been “trepanned.” Of the one hundred

thirty-five skeletons whose sex could be accurately determined by Dr.

Eaton,

one hundred nine were females. Furthermore, it was in the graves of the

females

that the finest artifacts were found, showing that they were persons of

no

little importance. Not a single representative of the robust male of

the

warrior type was found in the burial caves of Machu Picchu. Another striking fact

brought

out by Dr. Eaton is

that some of the female skeletons represent individuals from the

seacoast. This

fits in with Calancha’s statement that Titu Cusi tempted the monks not

only

with beautiful women of the highlands, but also with those who came

from the

tribes of the Yungas, or “warm valleys.” The “warm valleys” may be

those of the

rubber country, but Sir Clements Markham thought the oases of the coast

were

meant. Furthermore, as Mr.

Safford has

pointed out, among

the artifacts discovered at Machu Picchu was a “snuffing tube” intended

for use

with the narcotic snuff which was employed by the priests and

necromancers to

induce a hypnotic state. This powder was made from the seeds of the

tree which

the Incas called huilca or uilca,

which, as has been pointed out

in Chapter XI, grows near these ruins. This seems to me to furnish

additional

evidence of the identity of Machu Picchu with Calancha’s “Vilcabamba.” It cannot be denied

that the

ruins of Machu Picchu

satisfy the requirements of “the largest city, in which was the

University of

Idolatry.” Until some one can find the ruins of another important place

within

three days’ journey of Pucyura which was an important religious center

and

whose skeletal remains are chiefly those of women, I am inclined to

believe

that this was the “Vilcabamba Viejo” of Calancha, just as Espiritu

Pampa was

the “Vilcabamba Viejo” of Ocampo. In the interesting

account of

the last Incas

purporting to be by Titu Cusi, but actually written in excellent

Spanish by

Friar Marcos, he says that his father, Manco, fleeing from Cuzco went

first “to

Vilcabamba, the head of all that province.” In the “Anales

del Peru” Montesinos says that Francisco Pizarro, thinking

that the Inca

Manco wished to make peace with him, tried to please the Inca by

sending him a

present of a very fine pony and a mulatto to take care of it. In place

of

rewarding the messenger, the Inca killed both man and beast. When

Pizarro was

informed of this, he took revenge on Manco by cruelly abusing the

Inca’s

favorite wife, and putting her to death. She begged of her attendants

that

“when she should be dead they would put her remains in a basket and let

it

float down the Yucay [or Urubamba] River, that the current might take

it to her

husband, the Inca.” She must have believed that at that time Manco was

near

this river. Machu Picchu is on its banks. Espiritu Pampa is not. We have already seen

how Manco

finally established

himself at Uiticos, where he restored in some degree the fortunes of

his house.

Surrounded by fertile valleys, not too far removed from the great

highway which

the Spaniards were obliged to use in passing from Lima to Cuzco, he

could

readily attack them. At Machu Picchu he would not have been so

conveniently

located for robbing the Spanish caravans nor for supplying his

followers with

arable lands. There is abundant

archeological

evidence that the

citadel of Machu Picchu was at one time occupied by the Incas and

partly built

by them on the ruins of a far older city. Much of the pottery is

unquestionably

of the so-called Cuzco style, used by the last Incas. The more recent

buildings

resemble those structures on the island of Titicaca said to have been

built by

the later Incas. They also resemble the fortress of Uiticos, at

Rosaspata,

built by Manco about 1537. Furthermore, they are by far the largest and

finest

ruins in the mountains of the old province of Uilcapampa and represent

the

place which would naturally be spoken of by Titu Cusi as the “head of

the

province.” Espiritu Pampa does not satisfy the demands of a place which

was so

important as to give its name to the entire province, to be referred to

as “the

largest city.” It seems quite

possible that

the inaccessible,

forgotten citadel of Machu Picchu was the place chosen by Manco as the

safest

refuge for those Virgins of the Sun who had successfully escaped from

Cuzco in

the days of Pizarro. For them and their attendants Manco probably built

many of

the newer buildings and repaired some of the older ones. Here they

lived out

their days, secure in the knowledge that no Indians would ever breathe

to the conquistadores the secret

of their

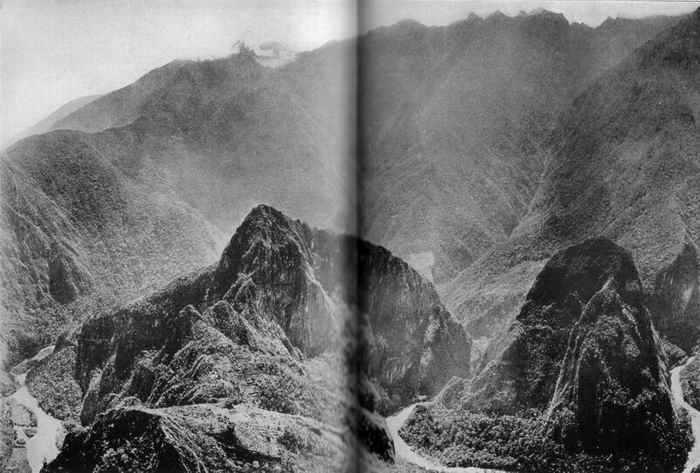

sacred refuge.  THE GORGES, OPENING WIDE APART, REVEALING UILCAPAMPA'S GRANITE CITADEL, THE CROWN OF INCA LAND: MACHU PICCHU When the worship of

the sun

actually ceased on the

heights of Machu Picchu no one can tell. That the secret of its

existence was

so well kept is one of the marvels of Andean history. Unless one

accepts the

theories of its identity with “Tampu-tocco” and “Vilcabamba Viejo,”

there is no

clear reference to Machu Picchu until 1875, when Charles Wiener heard

about it. Some day we may be

able to find

a reference in one

of the documents of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries which will

indicate

that the energetic Viceroy Toledo, or a contemporary of his, knew of

this

marvelous citadel and visited it. Writers like Cieza de Leon and Polo

de

Ondegardo, who were assiduous in collecting information about all the

holy

places of the Incas, give the names of many places which as yet we have

not

been able to identify. Among them we may finally recognize the temples

of Machu

Picchu. On the other hand, it seems likely that if any of the Spanish

soldiers,

priests, or other chroniclers had seen this citadel, they would have

described

its chief edifices in unmistakable terms. Until further light can be thrown on this fascinating problem it seems reasonable to conclude that at Machu Picchu we have the ruins of Tampu-tocco, the birthplace of the first Inca, Manco Ccapac, and also the ruins of a sacred city of the last Incas. Surely this granite citadel, which has made such a strong appeal to us on account of its striking beauty and the indescribable charm of its surroundings, appears to have had a most interesting history. Selected about 800 A.D. as the safest place of refuge for the last remnants of the old regime fleeing from southern invaders, it became the site of the capital of a new kingdom, and gave birth to the most remarkable family which South America has ever seen. Abandoned, about 1300, when Cuzco once more flashed into glory as the capital of the Peruvian Empire, it seems to have been again sought out in time of trouble, when in 1534 another foreign invader arrived — this time from Europe — with a burning desire to extinguish all vestiges of the ancient religion. In its last state it became the home and refuge of the Virgins of the Sun, priestesses of the most humane cult of aboriginal America. Here, concealed in a canyon of remarkable grandeur, protected by art and nature, these consecrated women gradually passed away, leaving no known descendants, nor any records other than the masonry walls and artifacts to be described in another volume. Whoever they were, whatever name be finally assigned to this site by future historians, of this I feel sure that few romances can ever surpass that of the granite citadel on top of the beetling precipices of Machu Picchu, the crown of Inca Land. THE

END |