| THE

STRAWBERRY.

A

genus of low perennial stemless herbs with runners, and leaves

divided into three leaflets; calyx open and flat; petals five, white;

stamens ten to twenty, sometimes more; pistils numerous, crowded upon

a cone-like head in the center of the flower. Seeds naked on the

surface of an enlarged pulpy receptacle called the fruit.

The

Strawberry belongs to the great Rose family, and the name of the

genus is Fragaria, from the Latin Fraya, its ancient

name. The French name of the strawberry is Fraisier; German,

Erdbeerpflanze; Italian, Planta di fragola; Dutch,

Aadbezie; Spanish, Freza. The South American

Spaniards

call the wild Strawberries of the country, Frutila.

The

well-known unstable character of the species makes it rather

difficult to determine the limit of variation, but the following

classification is in accord with the experience of practical

cultivators of the Strawberry as well as with the more recent

arrangement of the species in botanical works.

Fragaria

vesca. — The common wild Strawberry of Europe, including both

the White and Red Wood, also the annual and Monthly Alpine

Strawberries. Of the latter there are varieties with both white and

red fruit, growing in stools or clumps producing no runners, or very

sparingly. This species is also indigenous to North America and found

plentifully in our more northern States, and westward to the Rocky

Mountains, where it grows in the more elevated and cooler regions.

The plants are slender, with thin, often pale-green leaflets; fruit

small, oval, oblong, or sharp pointed; seeds quite prominent, never

depressed.

Fragaria

Californica — A low-growing species closely allied to the F.

vesca, but thought to be specifically distinct by some

botanists. The entire plant covered with spreading hairs; leaves

rather thin, wedge-shape and broadest at the tip. Flowers, small

white; calyx shorter than the petals, and often toothed or cleft;

fruit small, and seed as in vesca. On the hills and mountains

of California and in northern Mexico. There are no varieties of this

species in cultivation.

Fragaria

Virginiana. — The Wild Strawberry of the United States east of

the Rocky Mountains. Plant, with few or numerous scattering hairs;

upper surface of leaves often very dark green and shining, also very

large, thick, coarsely toothed. Flowers, white, in clusters on erect

scapes. Fruit red or scarlet, often with long neck; seeds in shallow

or deep pits on the surface of the receptacle. This species is the

parent of an immense number of varieties, like the Wilson, Boston

Pine, Early Scarlet, &c.

Variety.

— Illinoensis is found in the rich soils of the Western

States and is a larger and coarser growing plant, more villous or

hairy than the species, and the fruit is usually of a lighter color.

Some of the most popular varieties in cultivation are descended from

this indigenous western variety, such as the Charles Downing,

Downer's Prolific, &c.

Fragaria

Chiliensis. — A widely distributed species, especially on the

west coast of America, where it is found from Alaska on the north,

southward to California, and thence to Chili and other countries in

South America. It is usually a low-growing, spreading plant with

large thick cuneate, obovate leaflets, smooth and shining above; with

silky appressed hairs underneath. Fruit stalks very stout; flowers

white, large, often more than an inch in diameter and with five to

seven petals. Formerly these large flowered varieties from South

America were supposed to belong to a distinct species — the F.

grandflora, or Great-Flowering Strawberry; but more recent

investigation has shown that all belong to the one species, viz., F.

Chiliensis. This species is the parent of the most noted European

varieties, some of which have long been cultivated in this country,

but the varieties of the Virginian and Chili Strawberry have become

so intermingled by crossing that it is now scarcely possible to

trace their parentage.

Fragaria

Indica. — A small species from Upper India, with yellow

flowers, and small red, rather tasteless fruit. Often cultivated as a

curiosity and ornament, as the plants bear continuously through the

summer and autumn.

Fragaria

elatior. — Hautbois or Highwood Strawberry. Indigenous to

Europe, principally in Germany. Plants tall growing; fruit usually

elevated above the leaves, and the calyx strongly reflexed; petals

small, white; fruit brownish, pale red, sometimes greenish, with a

strong musky, and, to most persons, a disagreeable flavor. Only

sparingly cultivated. The plants are inclined to be dioecious, i.

e., the two sexes on different plants, even in their wild state.

HISTORY

OF THE STRAWBERRY.

How

the name of Strawberry came to be applied to this fruit is unknown,

as the old authors do not agree; some asserting that it was given it

because children used to string them upon straws to sell, while

others say that it took its name from the fact of straw being placed

around the plants in order to keep the fruit clean. Its name may not

have been derived from either of these, but from the appearance of

the plant; for when the ground is covered with its runners, they

certainly have much of the appearance of straw being spread over the

ground. We have found nothing conclusive on this point.

The

Strawberry does not appear to have been cultivated by the ancients,

or even by the Romans, for it is scarcely mentioned by any of their

writers, and then not in connection with the cultivated fruits or

vegetables. Virgil mentions it only when warning the shepherds

against the concealed adder when seeking flowers and Strawberries.

"Ye

boys that gather flowers and strawberries,

Lo,

hid within the grass a serpent lies."

Several

other ancient authors mention the Strawberry, but all refer to it as

a wild fruit, not cultivated in gardens; but there do not appear

to have been any improved varieties in cultivation until within

about one hundred years, although the wild plants were transferred to

gardens only in the fifteenth century, as we learn from works

published at that time.

Casper

Bauhin, in his "Pinax," published in 1623, mentions but

five varieties. Gerarde, in 1597, enumerates but three —

the white, red, and green fruited.

Parkinson,

in 1656, describes the Virginian and Bohemian, besides those

mentioned by Gerarde. Quintinis, in his "French Gardener,"

translated by Evelyn in 1672, mentions four varieties, and gives

similar directions for cultivation as practised at the present

time, viz., planting in August, removing all the runners as they

appear, and renewing the beds-every four years.

Only

four or five varieties are mentioned by any of the writers on

gardening earlier than about 150 years ago.

The

Pressant Strawberry, mentioned by Quintinius, was the first seedling

we find mentioned, and it was claimed to be superior to its parent,

the wild Wood or Alpine Strawberry of Europe.

The

Hautbois was long supposed to be indigenous to America, and both

Parkinson and Miller state that it came from this country, and the

former, in his "Paradisus Terrestris," 1629, says that

the Hautbois had been with them only of late days, having been

brought over from America. it is now known, however, that this

species is a native of Germany, where it is called the "Haarbeer."

The

Chili Strawberry was formerly supposed to have been introduced into

South America by the Spaniards from Mexico; and while plants may have

been introduced as stated, still, botanists assure us that the

same species is indigenous to both countries. This species was

introduced into France by a traveler named Frazier, in 1716, but

whether by seeds or living plants is not known. Philip Miller

introduced the Chili Strawberry into England in 1729, but he says it

was so unproductive that he finally discarded it. He also refers

to the irregular shape of the fruit, a characteristic of many of the

varieties of this species in cultivation at this time. The varieties

of the Chili Strawberry are usually larger and milder in flavor than

those of the Virginia Strawberry, but the plants are rarely as hardy

or succeed as well in our Northern States, except in sheltered

situations. In Europe, however, the varieties of the Chilean

Strawberry have long been preferred to those of the Virginian,

probably on account of their large size and mild flavor, as most of

our American varieties require a high temperature to develop their

saccharine properties.

No

improvement was made in the Strawberry by European gardeners until

the introduction of the American species, but it was not until the

beginning of the present century that practical experiments were made

in England for improving this fruit. In 1810 Mr. N. Davidson raised a

new variety, which was named the Roseberry. T. A. Knight raised the

Downton in 1816; Atkinson, the Grove End Scarlet in 1820; and in 1824

Keen's Seedling appeared. Knight raised the Elton in 1820. During the

twenty years from 1810 down to 1830 not more than a half dozen

improved varieties were produced in England, but Myatt soon followed

with his British Queen, which remained the leading variety of that

country for almost a half century.

The

French, German, Belgian, and other continental gardeners soon entered

the field, and now the Strawberry has become one of the most popular

fruits throughout Europe as well as in America.

Although

we possessed the materials from which we could have readily produced

new and improved varieties of the Strawberry, adapted to our soil and

climate, very little was attempted in this direction until long after

the Strawberry had become popular in Europe, and even when it began

to attract attention in this country, our fruit growers were content

to import varieties from abroad instead of attempting to raise new

and more valuable ones at home.

The

introduction of the Hovey in 1834 proved that it was possible to

raise large and productive varieties of the indigenous species, and

while a few cultivators may be said to have taken the hint, or avail

themselves of this discovery, the larger majority continued to import

varieties of the Chili Strawberry only to be sadly disappointed

with the result, for, with few exceptions, these are of little value

for cultivating in this country.

SEXUALITY

OF THE STRAWBERRY.

As

the Strawberry belongs to the Rose Family, its flowers should in

their natural state contain both stamens and pistils, and they

usually do, and the flowers are said to be perfect or bi-sexual. But

when plants are taken from their native habitats and placed under

cultivation, they often assume forms quite different from their

natural ones. Sometimes a particular organ is suppressed, while

others are enlarged, and thus we produce deformities and

monstrosities among almost every family of cultivated plants.

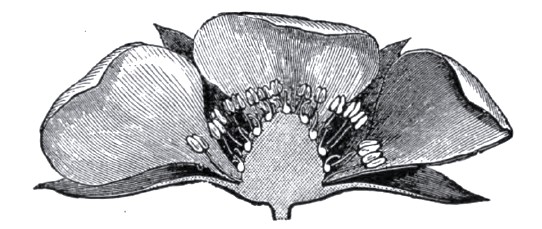

Fig.

1. — CROSS SECTION.

The

effects of stimulation or starvation, exposure and protection are

different upon different species of plants. The effect of

stimulation, through cultivation, upon the Rose proper appears to

have forced the stamens to enlarge and become petals circling

inward, and smothering the pistils, which are attached to the inside

of the rose-like receptacle. But in the Strawberry the receptacle is

the reverse of that of the rose, being conical as shown in an

enlarged cross-section of a flower, Fig. 1.

Every so-called seed of the Strawberry has

one style attached to it; consequently, it is a very important organ,

inasmuch as it is through this organ that the influence of the pollen

reaches the ovule or seed vessel. The stamens are situated on the

calyx, and they may be artificially removed or suppressed by nature,

in which case we would have what is called a pistillate flower, which

will produce fruit, if the pistils are fertilized from another flower.

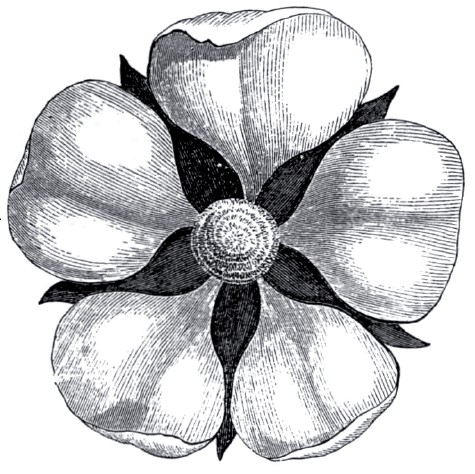

Fig. 2 — PISTILLATE FLOWER. USUAL SIZE

It

is not important whether a flower produces its own pollen or is

supplied from some other source.

Fig

3 — PISTILLATE FLOWER, ENLARGED

From

some unknown cause the F. Virginiana and the F. elatior

or Hautbois Strawberry of Europe occasionally give varieties in

which the stamens or male organs are undeveloped or entirely

wanting, and these unisexual plants have long been known as

pistillates; the Hovey Strawberry being one of the first to

attract special attention in this country. Fig. 2 represents

pistillate flower of the usual size, and in Fig. 3 the same enlarged.

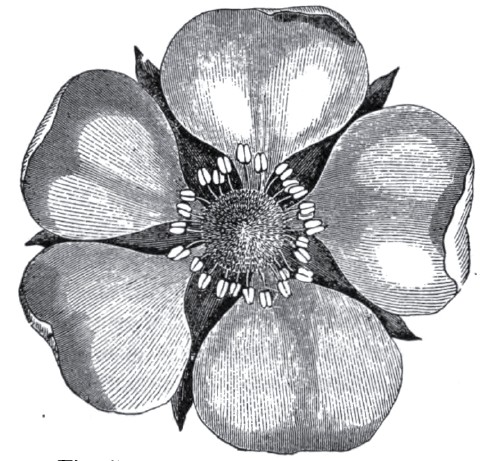

By comparing these with Fig. 4, a perfect flower, and the same

enlarged in Fig. 5, the difference may readily be seen.

Fig. 4 — PERFECT FLOWER.

These abnormal or pistillate varieties are

likely to occur among the seedlings of any of the improved or

cultivated varieties, and they are occasionally preserved and

multiplied, although in no instance that has come under my observation

have they proved to be superior to other varieties with perfect

flowers. That they are often preserved

and propagated must be considered more as a matter of personal pride

or opinion on the part of the originator, than a necessity -or

advantage to fruit growers in general. But so long as such imperfect

varieties are disseminated, they must be recognized, if for no other

purpose than to place the inexperienced propagator on his guard

against planting them alone, expecting to obtain a crop of

fruit. At one time it was supposed or claimed that these pistillate

varieties were, and would ever remain, totally barren unless

fertilized by pollen from some perfect flowered sort, but as the

stamens in the pistillate varieties are merely suppressed organs, it

is not at all rare to find an occasional one fully developed and

producing pollen. Where this occurs, and it is frequent in such

varieties as the Manchester, a moderate crop of fruit will be

produced where no pollen can reach the flowers from any other source.

But these partly undeveloped stamens cannot be depended upon for

supplying the necessary amount of pollen, and where varieties

designated as pistillates are cultivated, a perfect flowered one

should be grown near by, or even the plants intermingled in the same

bed or row. In cultivating a pistillate variety a person must set out

a perfect flowered one near by, in order to obtain a crop of

fruit from the imperfect; or, in other words, he must plant two

varieties to be certain of obtaining fruit from the one. There might

be some excuse for this doubling up if the pistillates were in any

way superior to the best of the bi sexual or perfect flowered

varieties, but as they are not, I fail to see the economy or

advantage of cultivating pistillates at all.

Fig

5 —PERFECT FLOWER, ENLARGED.

When

writing the first edition of this work, a quarter of a century ago, I

had occasion to refer to the assertion of certain cultivators, who

claimed that the pistillate varieties when properly fertilized were

more productive than those bearing perfect or bisexual flowers, but

facts to substantiate the claim were then wanting, and they certainly

have not appeared since, and it is very doubtful if any one

cultivating the Strawberry extensively would knowingly select a

pistillate in preference to a bisexual variety, provided both

were otherwise of equal value.

The

best pistillate varieties in cultivation may be fully equal in every

respect to the best bisexual or staminates, as they are often termed,

bat what I claim is that they are no better, besides being

objectionable because they must be fertilized by pollen from

some other source than their own flowers in order to bear a crop of

fruit. This defect in the flowers of the pistillate varieties makes

them worthless for cultivating alone in field or garden, for, in

order to secure a crop of fruit, a pollen-bearing variety must be

cultivated near by, and there is always more or less danger of the

plants intermingling, and it can only be prevented by care and

attention, while the runners are growing rapidly in summer.

There is, however, no real danger of the plants of different

varieties intermingling, if they are placed in adjoining beds or

rows, and the paths between kept free from runners; but cultivators

of the strawberry are often negligent in such matters and mixing of

varieties is the result.

INFLUENCE

OF POLLEN.

If

the small central organs or pistils of a Strawberry flower are not

fertilized by pollen from its own stamens or that from some other

plant, they soon die away and no fleshy receptacle or fruit is

produced. This pollen is an impalpable dust-like powder and yet so

important that the production of the Strawberry is dependent upon its

presence and potency. There must be not only an abundance of pollen,

but it mast be supplied by some closely allied species or variety of

the Strawberry, to be available. Pollen from the wild or uncultivated

Alpines or the Hautbois Strawberries will not fertilize the pistils

of the varieties of either the Virginia or Chili Strawberry,

neither will the pollen of the latter two species fertilize the

pistils of the former. But the Virginia and Chili Strawberries are so

closely allied that they readily hybridize; consequently, varieties

of either may be employed as the male or pollen-bearing for

pistillate varieties, provided, of course, that they bloom at

the same time, that is, the plants that are to yield the pollen and

those to receive it must bloom together.

There

is a great difference in the potency of the pollen of the

different varieties of plants of the same species, and it is not

at all rare to find bisexual plants the pollen of which will not

fertilize their own ovaries, while it is perfectly potent when

applied to the stigmas of another plant of the same species. Thus one

variety of the Strawberry may, in appearance, have perfect flowers,

and in the greatest abundance, and both stamens and pistils be fully

developed, and still ninety per cent. or even more of the flowers

will fail to produce fruit. In such instances of non-productiveness

we may be quite certain that there is something wrong in the sexual

organs, but it may be very difficult or impossible to determine

what it is.

At

a very extensive exhibition of Strawberries held at the American

Agriculturist office, N. Y., on June 18th, 19th and 20th, 1863, I was

awarded, among other prizes, the one offered for the "best

flavored variety." This was one of the many unnamed seedlings

then growing in my grounds, and, although a fine fruit in appearance

and flavor, it was utterly worthless owing to the unproductiveness of

the plants, and for this reason it was never distributed. The plants

were hardy, blossomed freely, and to all outward appearance the

flowers were perfect; still neither their own pollen or that from

other varieties would fertilize the pistils except in rare instances.

Every one who has attempted to raise new varieties of the Strawberry

must have had a similar experience, some being very productive and

others almost barren, and yet their sexual organs may have appeared

to be perfect. With a large majority of the bisexual or perfect

flowered varieties self-fertilization is the rule, but occasionally a

little outside aid in supplying pollen may be beneficial, and in

instances of this kind the raising of several varieties in close

proximity will largely increase the yield of fruit.

The

pistils of each flower must be supplied with a certain amount of

pollen from some source, else no fruit will be produced. If only a

part of the pistils are fertilized, a deformed fruit will be the

result, because the enlarging of the receptacle is for the sole

purpose of supporting the seeds resting upon its surface;

therefore, we may say, no seeds, no fruit. It has been claimed by

many vegetable physiologists that the influence of the pollen reaches

no further than the seed, but upon a close inspection of the

flower of a Strawberry we find that the receptacle, embryo seed and

all other parts are formed and in progress towards perfection before

any pollen is seen, and yet, if the latter fails to do its work, or

is impotent, the entire structure decays, and even the fruit

stems and their appendages wither away. In conducting some of my

earlier experiments with the strawberry, I noticed that the influence

of the pollen did extend beyond the seed, for it not only caused

the receptacle to enlarge and reach maturity but often changed its

form and flavor. This was most readily observed when employing

different staminate or perfect flowered varieties for supplying

pollen to the pistillates. But as in all similar experiments in the

fertilization of the ovaries, the results were not uniform, showing

that the female plant often exercises such a powerful influence over

its own seed and seed-vessels as to effectually obscure that of the

pollen-bearing or male plant. It is not to be supposed, however,

that because an effect is not prominently apparent that it does not

exist.

In

the first edition of "The Small Fruit Culturist," 1867, I

casually referred to this subject of the influence of the pollen upon

the character of the fruit, for I had previously discovered that in

raising the pistillate varieties, the staminate employed for

supplying their flowers with pollen had more or less influence on the

size and form of the fruit of the former. It is probably unnecessary

to state that this has been denied by many cultivators of the

Strawberry up to the present time, while others who have carefully

experimented for the purpose of determining the truth, admit that the

influence of the pollen does reach beyond the seed and is often

readily seen in the changed form of the fruit. But as I have

discussed this subject quite fully in another work,* it is only

necessary to say here that in cultivating pistillate varieties of the

Strawberry, it is better to select a large and good flavored one to

supply it with pollen than one that is small and of inferior quality.

*Propagation

of Plants.

|