| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VIII

WHAT BIRDS DO FOR US MAN'S

attitude

toward nature reveals a long step in his evolution. Shocked now and

again into

sudden recognition of her power by some mighty, destructive phenomenon

— an

earthquake, volcanic eruption, cyclone or flood — undeveloped man of

all

nations, trembling with terror, purchased ease of mind only by offering

sacrificial gifts to appease the wrath of imaginary gods, and then

straightway

relapsed into indifference. Her gentle, kindly ministrations every hour

of his

life, her marvelous beauties, impressed him not at all. Whenever he

thought of

nature it was of something mystic, beyond his comprehension, evil,

terrible. Even the

matchless

art of the Greeks reveals no appreciation of natural beauty beyond the

glorified human physique. For all the great masters among early

Christian

painters, for Raphael, Michael Angelo, Correggio, the lovely, smiling

Italian

Eden lying around them did not exist. It was literally beneath their

notice,

for their sight, lifted perpetually heavenward in search of subjects,

could

include nothing but clouds as natural settings for their Madonnas and

cherubim.

Not until the last century did artists come down to earth and discover

the

landscape for the people. And not until the last generation has nature

study,

the trained observation and love of nature, the most spiritualizing of

all his

lessons, formed part of the American child's education. One of our

greatest

religious thinkers has recently set himself the task of getting

acquainted with

the trees, birds and wild flowers around his summer home. "When I was a

boy," he says, half apologetically, "we never noticed these things.

The good people fixed their thoughts so steadfastly on the next world,

they

quite overlooked this. We left nature unread then, thinking that

everything

worth knowing had to be studied out of lesson books. And the idea of

knowledge

that obtained in a New England academy was almost mediæval. It bore

almost no

relation to the people's daily lives. Where nearly the entire

population earned

a living from the soil, absolutely nothing was done toward making the

people

understand it and love it. Is it any wonder that farming meant failure

so often

and that the ambitious young people rushed madly toward the cities? We

are only

just learning to enjoy nature, to open our blind eyes and see the world

around

us, to stop destroying and preserve the beneficent gifts lavished upon

us, to

utilize them intelligently, which is to agree with our Creator that His

creation is good." A NEW THING UNDER

THE SUN

In the quite sudden popular interest in nature recently manifest, birds have come in for, perhaps, the lion's share of attention. Unlike most movements, this is an absolutely new one in the history of the world, not a revival. One might have thought that so intensely practical a people as the Americans would have taken up economic ornithology first of all, have learned with scientific certainty which birds are too destructive for survival and which so valuable that every measure ought to be taken to preserve and increase them. In reality this has been the last aspect of the subject to receive attention. First came the classifiers — Wilson, Audubon, Baird, and Nuttall — the pioneers in systematic bird study. Thoreau was as a voice crying in the wilderness. His books lay in piles on the attic floor, unsold many years after his death. It remained for John Burroughs to awaken the popular enthusiasm for out-of-door life generally and for birds particularly, which is one of the signs of our times. An abandoned farm in New England Among the first acts passed in the Colonies were bounty laws, not only offering rewards for the heads of certain birds that were condemned without fair trial, but imposing fixed fines upon the farmer who did not kill his quota each year. Of course every man and boy carried a gun. The bounty system did much to foster the popular notion that everything in feathers is a legitimate target. Thus it is that "The

evil that birds do lives

after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones." For two

centuries

and a half this systematic destruction of birds, which blundered

ignorantly

along in every colony, state and territory, resulted in a loss to our

agriculture whose colossal aggregate would "stagger humanity" if,

indeed, our minds could grasp the estimated figures in dollars and

cents. Men

now living among us were absolutely the first to study the food of any

one

species of bird through an entire year and in various sections of the

country,

and to pass scientific judgment upon it only after laboratory tests of

the

contents of its stomach, — that final court of appeal. Through pressure

brought

to bear upon Congress by the American Ornithologists' Union, the

Department of

Agriculture was authorized in 1885 to spend a ridiculously small sum to

learn

the positive economic value of birds to us, a branch of scientific

research now

included under the Division of Biological Survey. Until that year all

the

scientific work that was done in this line could have been recorded in

a very

small volume indeed. A GENERAL WHITEWASHING

As might have been expected, when the white search-light of science beats upon the birds, none, not even the crow, appears as black as he has been painted. Only a few culprits among the hawks and owls, and only one little sinner not a bird of prey, stand convicted and condemned to die. When it came to a verdict on the English sparrow, after the most thorough and impartial trial any bird ever received, every thumb, alas ! was turned down. But having proven itself fittest to survive in the struggle for existence after ages of competition with the birds of the Old World, being obedient to nature's great law, it will defy man's legislation to exterminate it. Toilers in our over -populated cities, children of the slums, see at least one bird that is not afraid to live among them the year around. A much maligned ally of the farmer - the Red-shouldered Hawk One of the

first

good effects of the Government's scientific investigation of birds, and

the

consequent whitewashing of bird characters that ensued, was the

withdrawal of

bounties by many states. Pennsylvania, for instance, woke up to realize

that

her notorious "scalp act" had lost her farmers many millions of

dollars through the ravages of field mice, because the wholesale

slaughter of

all hawks and owls, regardless of their food and habits, had been

systematically

encouraged. A little knowledge on the part of legislators, backed by an

immense

amount of popular ignorance and prejudice against all of the so-called

birds of

prey, proved to be a very dangerous thing. Even better than the

withdrawal of

bounties is the action taken by many states to protect the birds.

Instead of

laying stress upon only the apparent evil in nature, as undeveloped

pagans did,

we are at last putting the emphasis where it rightly belongs, — upon

the good. THE PARTITION OF

APPETITES

Whoever

takes any

notice of the birds about us cannot fail to be impressed with the

regulation of

that department of nature's housekeeping entrusted to them. The labor

is so

adjusted as to give to each class of birds duties as distinct as a

cook's from

a chambermaid's. One class of tireless workers is bidden to sweep the

air and

keep down the very small gauzy-winged pests such as mosquitoes, gnats,

and

midges. Swallows dart and skim above shallow water, fields, and

marshes; purple

martins circle about our gardens; swifts around the roofs of our

houses,

night-hawks and whippoorwills through the open country, all plying the

air for

hours at a time. Some, which fly with their mouths open, need not pause

a

moment for refreshments. On

distended upper

branches, preferably dead ones, on fence rails, posts, roofs, gables

and other

points of vantage where no foliage can impede their aerial sallies, sit

kingbirds, pewees, phoebes, and kindred dusky, inconspicuous

flycatchers, ready

to launch off into the air the second an insect heaves in sight, snap

it up

with the click of a satisfied beak, then return to their favorite

look-out and

patiently wait for another. This class of birds keeps down the larger

flying

insects. For generations the kingbird has been condemned as a destroyer

of

bees. Rigid investigation proves that he eats very few indeed, and

those mostly

drones. On the contrary, he destroys immense numbers of robber-flies or

bee-killers, one of the worst enemies the bee farmer has. The mere fact

that

the kingbird has been seen so commonly around apiaries was counted

sufficient

circumstantial evidence to condemn him in this land of liberty. But

after a

fair trial it was found that ninety per cent of his food consists of

insects

chiefly injurious: robber-flies, horse-flies, rose chafers, clover

weevils,

grasshoppers, and orchard beetles among others. THE CARE OF FOLIAGE

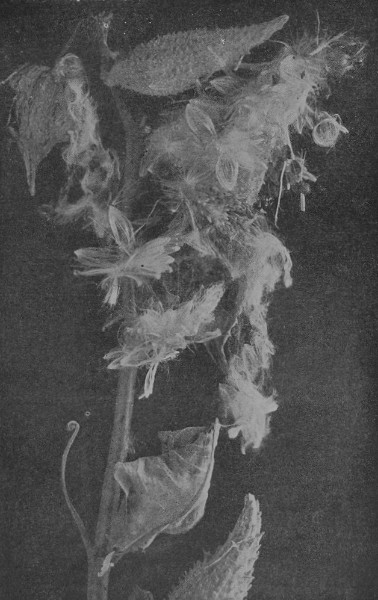

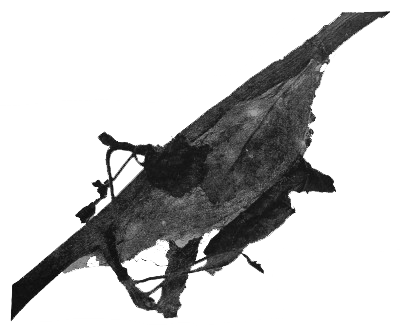

To such birds as haunt the terminal twigs of trees and shrubbery — the warbler tribe and the vireos, chiefly — was assigned the duty of cleaning the foliage on the ends of the branches, where many kinds of insects deposit their eggs that their young may have the freshest, tenderest leaves to feed upon. Some few warblers, in the great family, confine their labors to the ground and undergrowth, it is true, and a few others pick their living out of the trunks of trees, but they are the exceptions which prove the rule. Countless millions of larva, plant lice, ants, canker-worms, leaf-hoppers, flies, and the smaller caterpillars go to supply the tireless energy of these charming little visitors each time they migrate through our neighborhood. Generally speaking, the vireos, or greenlets, are less nervous and more deliberate and thorough in their search than the warblers. Cocking their heads to one side, they scrutinize the under half of the leaves where insects have sought protection from just such sharp eyes as theirs, as well from rain and sun. After a warbler has snatched a hasty lunch in any given place, the vireo can follow him and find a square meal to be enjoyed at leisure. Parasites on Caterpillar host. What the vireo sees under a leaf But vireos and warblers, which are smaller than sparrows, however efficient as destroyers of the lesser insects, would be powerless to grapple with the larger pests found in the same places. Accordingly, another gang of larger feathered workers helps take care of the foliage for that most thorough of housekeepers, Dame Nature. Hidden among the foliage of trees and shrubbery, an immense army of feathered workers — many of our most beautiful birds and finest songsters among them — serve her without hire, and during longer working hours than any trades-union songsters would allow. Thrushes, bluebirds, robins, mockingbirds, orioles, catbirds, thrashers, wrens, and tanagers — these and many others keep up a lively insect hunt throughout a long sojourn among us, coming when the first insects emerge in the spring and not wholly giving up the chase until the last die or become dormant with the coming of winter. What could a little warbler do with tent caterpillars, for example? But slim, large cuckoos glide among the leafy branches and count themselves lucky to enter a neighborhood infested by them. The sudden appearance of a new insect pest often attracts large numbers of birds not commonly seen in the neighborhood. If dead or mutilated larvæ of tent caterpillars are seen near the torn tent it was probably opened by an oriole, for the cuckoo does his work more thoroughly, leaving no remains. The black-billed cuckoo has been an invaluable ally of the farmers in their herculean task of destroying the gypsy moth, an alarming pest which, although only recently introduced from Europe, has already laid waste large sections of New England. The stomach of a single yellow-billed cuckoo examined contained two hundred and seventeen fall web- worms! Hairs have been considered a means of protection adopted by many caterpillars. Most birds will not touch the hairy kind. But cuckoos are not so fastidious. The walls of their stomachs are some times as closely coated with hairs as a gentleman's beaver hat. Caterpillars are also the most important item on the Baltimore oriole's bill of fare, of which eighty-three per cent is insect food gleaned among the foliage of trees. Click beetles, which infest every kind of cultivated plant, and their larvæ, known as wire-worms, destroy millions of dollars' worth of farm produce every year. Now, there are over five hundred species of them in North America, and the oriole, which eats them as a staple and demolishes very many other kinds of beetles, wasps, bugs, plant-lice, craneflies, grasshoppers, locusts, and spiders, should win opinions as golden as his feathers for this benefaction alone. It has been said that were all the insects to perish, all the flowers would perish too, which is not half so true as that were all the birds to perish men would speedily follow them. At the end of ten years the insects, unchecked, would have eaten every green thing off the earth! A feast of tent caterpillars for the cuckoo "Most birds will not touch the hairy kind" An important item on the Baltimore Oriole's bill of fare (smooth Caterpillar) THE BIRDS THAT HAVE

CHARGE OF THE BARK

For obvious reasons, then, many crawling insects hide themselves under the scaly bark of trees or in holes laboriously tunneled in decaying wood; others deposit their eggs in such secret places. When they die a natural death at the close of summer it is with the happy delusion that the next generation of their species, sleeping in embryo, is perfectly safe. But see how long it takes a woodpecker to eat a hundred insect eggs and empty a burrow of every grub in it! Inspecting each crevice where moth or beetle might lay her eggs, he works his way around a tree from bottom to top, now stopping to listen for the stirring of a borer under the smooth, innocent-looking bark, now tapping at a suspicious point and quickly drilling a hole where there is a prospect of heading off his victim. Using his bill as a chisel and mallet and his long tongue as a barbed spear to draw the grub from its nethermost hiding place, he lets nothing escape him. Boring beetles, tree-boring caterpillars, timber ants, and other insects which are inaccessible to other birds, must yield their reluctant bodies to that merciless barbed tongue. Our little friend downy and the hairy woodpecker, the most beneficial members of the family, the flicker that descends to the ground to eat ants, the red-headed woodpecker that intersperses his diet with grasshoppers, even the much-maligned sapsucker that pays for his intemperate drinks of freshly drawn sap by eating ants, grasshoppers, flies, wasps, bugs, and beetles, — to these common woodpeckers and to their less neighborly kin, more than to any other agency, we owe the preservation of our timber from hordes of destructive insects. Preservers of timber: Downy Woodpeckers But

acknowledgment

of this deep obligation must not cause us to overlook the nuthatches,

brown

creepers, chickadees, kinglets, and such other helpers that keep up

quite as

tireless a search for insects on the tree trunks and larger limbs as

the more

perfectly equipped woodpeckers. "In a single day a chickadee will

sometimes eat more than four hundred eggs of the apple plant-louse,"

says

Professor Clarence Moores Weed, "while throughout the winter one will

destroy an immense number of the eggs of the canker-worm."

CARETAKERS OF THE

GROUND FLOOR

Hidden in

the

grasses at the foot of the trees, among the undergrowth of woodland

borders,

under the carpet of last year's leaves, and buried in the ground

itself, are

insect enemies whose name is legion. Among the worst of them are the

white

grubs — the larvæ of May beetles or June bugs — and the wireworms which

attack

the roots of grasses and the farmers' grain; the maggots of crane-flies

which

do their fatal work under cover of darkness in the soil; root- and

crown-borers

which destroy annually fields of timothy, clover, and herds-grass;

grasshoppers, locusts, chinch bugs, cutworms and army worms that have

ruined

crops enough to pay the national debt many times over. But what a

hungry

feathered army rushes to their attack! And how much larger would that

army have

been if, in our blind stupidity or ignorance, we had not killed off

billions of

members of it! Some habitual fruit- or seed-eating birds of the trees descend to the ground at certain seasons, or when an insect plague appears, changing their diet to suit nature's special need; others "lay low" the year around, waging a perpetual insect war. First in that war stands the meadow-lark. It is estimated that every meadow-lark is worth over one dollar a year to the farmers, if only in consideration of the grasshoppers it destroys; and as insects constitute seventy-three per cent of its diet, the remainder being seeds of weeds chiefly, the farmer might as well draw money out of the bank and throw it in the sea as to allow the meadow-lark to be shot; yet it has long been classed among game birds — a target for gunners. An appetizing dinner "The

average

annual loss which the chinch bug causes to the United States cannot be

less

than twenty million dollars," says Dr. L. O. Howard, of the Department

of

Agriculture. "It feeds on Indian corn and on wheat and other small

grains

and grasses, puncturing the stalks and causing them to wilt."

Incalculable

numbers of this pest are eaten every season by Bob Whites, or quail,

which, it

will be seen, are perhaps as valuable to the American people when

roaming

through our grain fields as when served on toast to our epicures.

Blackbirds,

crows, robins, native sparrows, chewinks, oven-birds, brown thrashers,

ground

warblers, woodcock, grouse, plovers, and the yellow-winged woodpeckers

or

flickers, which feed on ants (whose chief offense is that they protect

aphides

or plant lice to "milk" them) — these, and many other birds

contribute to our national wealth more than the wisest statistician

could

estimate. Many old farmers will wish at least the crow or the blackbird

removed

from this white list, but scientific experts have proved that the

workman is

worthy of his hire — that the birds which destroy enormous numbers of

white

grubs, army worms, cutworms and grasshoppers in the fields are as much

entitled

to a share of the corn as the horse that plows it or the ox that treads

it out.

The evil results fol lowing a disturbance of nature's nice balances

rest on no

scientific theories but on historic facts. Protective bird laws, which

very

quickly increase the insect police force, add many million dollars

annually to

the permanent wealth not only of such enlightened states as have

adopted them,

but to the country at large, for birds, like the rain, minister to the

just and

the unjust. And the rising generation of farmers is the first to be

taught this

simple economic fact! WEED DESTROYERS

Weeds have

been

defined as plants out of place, and agriculture as an everlasting war

against

them. What natural allies has the pestered farmer? Happily, the sparrows and finches, among the most widely distributed, prolific and hardy of birds, are his constant co-workers, some members of their large clan being with him wherever he may live every day in the year. Nearly all, it is true, vary their diet with insects, but surely they are no less welcome on that account!  A tempting lunch - Milk-weed seeds for the finches "Certain

garden weeds produce an incredible number of seeds," says Dr. Sylvester

Judd, of the Biological Survey. "A single plant of one of these species

may mature as many as a hundred thousand seeds in a season, and if

unchecked

would produce in the spring of the third year ten billion plants." With

these figures in mind, it is easy to account for the exceedingly rapid

spread

of certain weeds from the Old World — daisies and wild carrot, for

example — of

comparatively recent introduction here. The great majority of weeds

being

annuals, the parent plant dying after frost or one season's growth and

the

species living only in embryo during the remainder of the year, it

follows that

seed-eating birds are of enormous practical value. Even the despised

English

sparrows do great good as weed destroyers

— almost enough to tip the scales of justice in their

favor. In autumn,

what noisy flocks of the little gamins settle on our lawns and clean

off seeds

of crab-grass, dandelion, plantain, and other upstarts in the turf! The

song

sparrow, the chipping sparrow, the white-throated sparrow, and the

goldfinch

are glad enough to follow after their English cousin and get out the

dandelion

seeds exposed after he cuts off several long, protecting scales of the

involucre. Because of his special preference, however, the little black

and

yellow goldfinch, an unequaled destroyer of the composite weeds, is

often

called the thistle-bird. The few tender sparrows which must winter in

the south

are replaced in autumn by hardier relatives, whose feeding grounds at

the far

north are buried under snow; by juncos, snowflakes, longspurs,

redpolls, grosbeaks,

and siskins, all of which are busy gleaners among the plow furrows in

fallow

land, and the brown weed-stalks that flank the roadsides or rear

themselves

above the snowy fields. In enumerating the little weeders that serve us

without

so much as a "thank you" — and fifty different birds are on this

list — we must not forget the horned lark, chewink, blackbirds,

cowbird,

grackles, meadow-lark, bobolink, ruffed grouse, Bob White, and the

mourning

dove. Even the

most

sluggish birds — and some of the finch tribe have a reputation for

being that —

are fast livers compared with men. Their hearts beat twice as fast as

ours; we

should be feverish were our blood less hot; therefore, the quantity of

food

required to sustain such high vitality, especially in winter, is

relatively

enormous. A tree sparrow will eat one hundred seeds of pigeon-grass at

a single

meal, and a snowflake, observed in a Massachusetts garden one February

morning,

picked up over a thousand seeds of pigweed for breakfast.

BUSINESS CO-PARTNERSHIPS

In view of the enormous amount of work certain birds are capable of doing for the farmers, how many take any pains to secure their free services continuously; to get help from them as well as from the spraying machine and insect powder on which so much time and money are spent annually? The truth is that very few farmers indeed realize the true situation; therefore the intelligent, the obvious thing to be done is generally neglected. How a successful peach grower in Georgia makes the purple martins work for him One of the most successful fruit-growers in Georgia, whose luxuriant orchard and luscious peaches are famous throughout the market, entered some time ago into a systematic, business-like understanding with a number of birds whose special appetites for special insect pests make them invaluable partners. Up and down through the long avenues of trees he erected poles from twenty to thirty feet high, and from them swung gourds for the purple martins to nest in, because he has found this bird his chief ally in keeping down the curculio beetle, the most destructive foe, perhaps, the fruit-grower has to fight. Through its attack alone the value of a single peach orchard has been reduced from ten thousand dollars to nothing in three weeks! The damage this little beetle does to American fruit-growers annually amounts to many millions of dollars. Just when the martins return from the tropics, it is emerging from its winter hibernation. And when the nuptial flight of the curculio and the shot-hole borer and of the root -borer moth occurs, it ought to be obvious to every fruit-grower that he cannot have too many insectivorous birds about. Bluebirds, which readily accept invitations to nest in boxes placed on poles and trees, destroy immense numbers of insects taken from the trees, ground, and air. In the Georgia orchard referred to, titmice, chickadees, and nuthatches are attracted by raw peanuts placed in the trees and scattered over the ground. Once these favorite nuts were discovered, this family of birds likewise joined the firm which, with the addition of the owner of the estate, now consists of purple martins, barn swallows, chimney-swifts, bluebirds and wrens. Of course they have numerous assistants that come and go, but these are the recognized partners, both full-fledged and juniors, with homes on the place. And all draw enormous dividends from it in that unique and happy manner which greatly increases the cash revenues of the business. Perhaps the junior partners, the fledglings, with appetites bigger than their bodies (for many eat more than their weight of food every twenty-four hours) , are of greater value than the seniors. Even seed-eating birds, as we have seen in a previous chapter, feed insects to their nestlings: an indigo bunting mother does not hesitate to ram a very large grasshopper down her very small baby's throat after she has nipped off the wings. Junior partners: young house-wrens almost ready to earn their own living "An Indigo Bunting mother does not hesitate to ram a large grasshopper down her small baby's throat after she has nipped off the wings"

PARTNERSHIPS IN

NATURE

Just as many insects have resorted to curious and ingenious devices to avoid the birds' attention, so many trees, shrubs, and plants, with ends of their own to be gained, take great pains to attract it. Some insects mimic with their coloring that of their surroundings: one must look sharp be‑ fore discovering the glaucous green worm on the glaucous green nasturtium leaf. Some, like the milkweed butterfly, secrete disagreeable juices to repel the birds, and other butterflies, which secrete none, fool their foes by bearing a superficial resemblance to it. Others, like the walking-stick, assume a form that can scarcely be distinguished from the objects it frequents. With what pains does the caterpillar draw together the edges of a leaf and hide within it, sleeping until ready to emerge into its winged stage, if by chance a pair of sharp eyes does not discover it at the beginning of its nap, and a sharper beak tear it ruthlessly from the snug cradle! Children who gather cocoons in the autumn are often disappointed to find so many already empty. They forget that. thousands of hungry migrants have been out hunting every morning before they left their beds. No cradle yet woven is too tough for some bird to tear open for the luscious, fat morsel within. To the Baltimore oriole looking for a dinner, the strong cocoon of the great cecropia moth yields one as readily as another; and I have watched an orchard oriole that brought her young family to feast in a tamarix bush in the garden, pick forty-seven basket-worms from their cleverly concealed baskets in fifteen minutes. A slim enough dinner far any bird that discovers it - The walking-stick "For how much of earth's beauty are not birds, the seed carriers, responsible!" Cedar bird in wild-grape vine But how the bright berries, hanging on the dogwood, mountain ash, pokeweed, choke-cherry, shadbush, partridge vine, wintergreen, bittersweet, juniper, Virginia creeper, and black alder, cry aloud to every passing bird, "EAT ME," like Alice's marmalade in Wonderland! Many plants depend as certainly on the birds to distribute their seeds as on bees and other insects to transfer the pollen of their flowers. It is said that the cuckoo-pint or spotted arum of Europe, a relative of our jack-in-the-pulpit, actually poisons her messengers carrying seed, because the decaying flesh of the dead birds affords the most nourishing food for her seed to germinate in. Happily we have no such cannibalistic pest here. Our wild trees, shrubbery, plants, and vines are honorable partners of the birds. They feed them royally, asking in return only that the undigested seeds or kernels which pass through the alimentary canal uninjured may be dropped far away from the parent plant, to found new colonies. For how much of the earth's beauty are not birds, the seed-carriers, responsible!  The cecropia moth's large, strong cocoon must likewise yield its contents to the oriole Up-to-date-farmers

who wish to protect their cultivated fruits have learned that birds

actually

have the poor taste to prefer wild ones, and so they plant them on the

outskirts of the farm, along walls and fences. They have also learned

that many

birds puncture grapes and drink fruit juice simply because they are

thirsty.

Pans kept filled with fresh water compete successfully with the grape

arbor.

SAINTS AND SINNERS

Hawks and owls may be so labeled, yet it would be difficult, if not impossible, to convince some people that there is a saint in the group. There is an instinctive popular hatred of every bird of prey, — a hatred so unreasoning and unrelenting that it is well-nigh impossible to secure legislation to protect some of the farmers' most beneficial friends. After condemning the duck hawk for its villainies upon our wild water-fowl, and that powerful brigand, the goshawk, for audaciously carrying off full-grown poultry, ruffed grouse and rabbits, and Cooper's hawk, a deep-dyed chicken stealer, whose aggregate misdeeds are greater than any others (simply because his species is the most numerous), and his smaller prototype, the sharp-shinned hawk for destroying little chickens and song-birds, Dr. Fisher, who made an exhaustive study of hawks and owls for the Government, recommends clemency toward all the others. He investigated forty birds of prey found within our borders. A Self-constituted Health Department: Vultures feeding on carrion "It would be just as rational to take the standard for the human race from highwaymen and pirates as to judge all hawks by the deeds of a few," he says. "Even when the industrious hawks are observed beating tirelessly back and forth over the harvest fields and meadows, or the owls are seen at dark flying silently about the nurseries and orchards, busily engaged in hunting the voracious rodents which destroy alike the grain, produce, young trees, and eggs of birds, the curses of the majority of farmers and sportsmen go with them, and their total extinction would be welcomed. How often are the services to man misunderstood through ignorance! The birds of prey, the majority of which labor day and night to destroy the enemies of the husbandman, are persecuted unceasingly, while that gigantic fraud — the house cat — is petted and fed and given a secure shelter from which it may emerge to spread destruction among the feathered tribe. The difference between the two can be summed up in a few words: Only three or four birds of prey hunt birds when they can procure rodents for food, while a cat seldom touches mice if she can procure birds or young poultry. A cat has been known to kill twenty young chickens in a day, which is more than most raptorial birds destroy in a lifetime." A Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: the horned owl Hawks and

owls

admirably supplement each other's work. One group hunts while the other

sleeps.

The owls usually remain in a chosen neighborhood through the winter,

while the

hawks go south. We are never left unprotected. In consideration of the

overwhelming amount of good these unthanked friends do us, can we not

afford to

be to their faults a little blind? A VOLUNTEER HEALTH

DEPARTMENT

In the southern states, Cuba, and the adjacent islands, the great dark vultures that go sailing high in air express the very poetry of motion; but surely their terrestrial habits have to do with the very prose of existence, for self-constituted health officers are they, scavengers of the fields, that rid them of putrefying animal matter. Instead of burying a dead chicken, dog, cat, or even a large domestic animal, the easy-going Negro lets it lie where it dropped, knowing full well that before it becomes offensive the vultures will have begun to feed upon it. In some of the smaller cities the vultures mingle freely with the loungers about the market-place, gorging upon the refuse thrown about for the only street cleaners in sight. Where robins, woodpeckers, and many species of small song-birds are so lightly regarded as to be killed in shocking quantities and not always for food, the vultures are carefully protected by the Southern people, who, not yet realizing the greater value of insectivorous birds to the farmer, do nevertheless know enough to throw the arm of the law around their feathered scavengers. Sea gulls in the wake of a garbage scow cleansing New York harbor of floating refuse As if enough services that birds render us had not already been enumerated in this list, — which is merely suggestive and very far indeed from being complete, — the birds that rid our beaches of putrefying rubbish must not be forgotten. While several sea and beach birds share this task, it is to the gulls that we are chiefly indebted. In the wake of garbage scows that put out to deep water from the harbors of the seacoast and Great Lakes where our large cities are situated, and following the ocean liners for the food thrown overboard from the ship's galleys; or resting in the estuaries of the larger rivers where the refuse floats down toward the tide, flocks of strong-winged gulls may be seen hovering about with an eye intently fastened on every floating speck. Enormous feeders, gulls and terns cleanse the waters as vultures do the land. Millions of these graceful birds that enliven the dullest marine picture have been sacrificed for no more worthy end than to rest entire or in mutilated sections on women's hats! But now that the people begin to understand what birds do for us, a happier day is dawning for them all. |