| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER VI THE LANDING OF STORES AND EQUIPMENT FEBRUARY 3-22, 1908 Blizzard in McMurdo Sound, February 18-21: Nimrod sails for New Zealand, February 22 We had hardly

started work again

when a strong breeze sprung up with drifting snow. The ship began to

bump

heavily against the ice-foot and twice dragged her anchors out, so, as

there

seemed no possibility of getting ahead with the landing of the stores

under

these conditions, we steamed out and tied up at the main ice-face,

about six

miles to the south, close to where we had lain for the past few days.

It blew

fairly hard all day and right through the evening, but the wind went

down on

the afternoon of the 5th, and we returned to the bay that evening. We lost no time

in getting the

ponies ashore. This was by no means an easy task, for some of the

animals were

very restive, and it required care to avoid accident to themselves or

to us.

Some time before we had thought of walking them down over a gang-plank

on to

the ice, but afterwards decided to build a rough horse-box, get them

into this,

and then sling it over the side by means of the main gaff. We covered

the decks

with ashes and protected all sharp projections with bags and bales of

fodder.

The first pony went in fairly quietly, and in another moment or two had

the

honour of being the pioneer horse on the Antarctic ice. One after

another the

ponies were led out of the stalls into the horse-box and were slung

over on to

the ice. They all seemed to feel themselves at home, for they

immediately

commenced pawing at the snow as they are wont to do in their own

far-away

Manchurian home, where, in the winter, they scrape away the snow to get

out the

rough tussocky grass that lies underneath. It was 3.30 A.M. on the

morning of

the 6th before we got all the ponies off the ship, and they were at

once led up

on to the land. The poor beasts were naturally stiff after the constant

buffeting they had experienced in their narrow stalls on the rolling

ship for

over a month, and they walked very stiffly ashore. They negotiated

the tide-crack all

right, the fissure being narrow, and were soon picketed out on some

bare earth

at the entrance to a valley which lay about fifty yards from the site

of our

hut. We thought that this would be a good place, but the selection was

to cost

us dearly in the future. The tide-crack played an important part in

connection

with the landing of the stores. In the polar regions, both north and

south,

when the sea is frozen over, there always appears between the fast ice,

which

is the ice attached to the land, and the sea ice, a crack which is due

to the

sea ice moving up and down with the rise and fall of the tide. When the

bottom

of the sea slopes gradually from the land, sometimes two or three

tide-cracks

appear running parallel to each other. When no more tide-cracks are to

be seen

landwards, the snow or ice-foot has always been considered as being a

permanent

adjunct to the land, and in our case this opinion was further

strengthened by

the fact that our soundings in the tide-crack showed that the ice-foot

on the

landward side of it must be aground. I have explained this fully, for

it was

after taking into consideration these points that I, for convenience

sake,

landed the bulk of the stores below the bare rocks on what I considered

to be

the permanent snow-slope. About 9 A.M. on

the morning of

February 6 we started work with sledges, hauling provisions and pieces

of the

hut to the shore. The previous night the foundation posts of the hut

had been

sunk and frozen into the ground with a cement composed of volcanic

earth and

water. The digging of the foundation holes, on which job Dunlop, Adams,

Joyce,

Brocklehurst, and Marshall were engaged, proved hard work, for in some

cases

where the hole had to be dug the bed-rock was found a few inches below

the

coating of the earth, and this had to be broken through or drilled with

chisel

and hammer. Now that the ponies were ashore it was necessary to have a

party

living ashore also, for the animals would require looking after if the

ship

were forced to leave the ice-foot at any time, and, of course, the

building of

the hut could go on during the absence of the ship. The first shore

party

consisted of Adams, Marston, Brocklehurst04ackay, and Murray, and two

tents

were set up close to the hut, with the usual sledging requisites,

sleeping-bags, cookers, &c. A canvas cover was rigged on some

oars to serve

as a cooking-tent, and this, later on, was enlarged into a more

commodious

house, built out of bales of fodder. The first

things landed this day

were bales of fodder for the ponies, and sufficient petroleum and

provisions

for the shore party in the event of the ship having to put to sea

suddenly

owing to bad weather. For facility in landing the stores, the whole

party was

divided into two gangs. Some of the crew of the ship hoisted the stores

out of

the hold and slid them down a wide plank on to the ice, others of the

ship's

crew loaded the stores on to the sledges, and these were hauled to land

by the

shore party, each sledge having three men harnessed to it. The road to

the

shore consisted of hard, rough ice, alternating with very soft snow,

and as the

distance from where the ship was lying at first to the tide-crack was

nearly a

quarter of a mile, it was strenuous toil, especially when the

tide-crack was

reached and the sledges had to be pulled up the slope. After the first

few

sledge-loads had been hauled right up on to the land, I decided to let

the

stores remain on the snow slope beyond the tide-crack, where they could

be

taken away at leisure. The work was so heavy that we tried to

substitute

mechanical haulage in place of man haulage, but had to revert to our

original

plan, and all that morning we did the work by man haulage. During the

lunch

hour we shifted the ship about a hundred yards nearer the shore

alongside the

ice-face, from which a piece had broken out during the morning, leaving

a level

edge where the ship could be moored easily. Just as we were

going to commence

work at 2 P.M. a fresh breeze sprang up from the south-east, and the

ship began

to bump against the ice-foot, her movement throwing the water over the

ice. We

were then lying in a rather awkward position in the apex of an angle in

the bay

ice, and as the breeze threatened to become stronger, I sent the

shore-party on

to the ice, and, with some difficulty, we got clear of the ice-foot.

The breeze

freshening we stood out to the fast ice in the strait about six miles

to the

south and anchored there. It blew a fresh breeze with drift from the

south-east

all that afternoon and night, and did not ease up till the following

afternoon.

Thus, unfortunately two valuable working days were lost. When I went

ashore I found that the

little party left behind had not only managed to get up to the site of

the hut

all the heavy timber that had been landed, but had also stacked on the

bare

land the various cases of provisions which had been lying on the snow

slope by

the tide-crack. We worked till 2 A.M. on the morning of the 9th, and

then

knocked off till 9 A.M. Then we commenced again, and put in one of the

hardest

day's work one can imagine, pulling the sledges to the tide-crack and

then

hauling them bodily over. Hour after hour all hands toiled on the work,

the

crossing of the tide-crack becoming more difficult with each succeeding

sledge-load, for the ice in the bay was loosening, and it was over

floating,

rocking pieces of floe with gaps several feet wide between them that we

hauled

the sledges. In the afternoon the ponies were brought into action, as

they had

had some rest, and their arrival facilitated the discharge, though it

did not

lighten the labours of the perspiring staff. None of our party were in

very

good condition, having been cooped up in the ship, and the heavy cases

became

doubly heavy to our arms and shoulders by midnight. Next day the

work continued, the ice

still holding in, but threatening every minute to go out. If there had

been

sufficient water for the ship to lie right alongside the shore we would

have

been pleased to see the ice go out, but at the place where we were

landing the

stores there was only twelve feet of water, and the Nimrod,

at this time, drew fourteen. We tried to anchor one of the

smaller loose pieces of bay ice to the ice-foot, and this answered

whilst the

tide was setting in. As a result of the tidal movement, the influx of

heavy

pack in the bay where we were lying caused some anxiety, and more than

once we

had to shift the ship away from the landing-place because of the heavy

floes

and hummocky ice which pressed up against the bay ice. One large berg

sailed in

from the north and grounded about a mile to the south of Cape Royds,

and later

another about the same height, not less than one hundred and fifty

feet, did

the same, and these two bergs were frozen in where they grounded and

remained

in that position through the winter. The hummocky pack that came in and

out

with the tide was over fifteen feet in height, and, being of much

greater depth

below water, had ample power and force to damage the ship if a breeze

should

spring up. When we turned

to after lunch, and

before the first sledge-load reached the main landing-place, we found

that it

would be impossible to continue working there any longer, for the small

floe

which we had anchored to the ice had dragged out the anchor and was

being

carried to sea by the ebbing tide. Some three hundred and fifty yards

further

along the shore of the bay was a much steeper ice-foot at the foot of

the

cliffs, and a snow slope narrower than the one on which we had been

landing the

provisions. This was the nearest available spot at which to continue

discharging. We hoped that when the ship had left we could hoist the

stores up

over the cliff; they would then be within a hundred yards of the hilt,

and,

after being carried for a short distance, they could be rolled down the

steep

snow slope at the head of the valley where it was being built. All this

time

the hut-party were working day and night, and the building was rapidly

assuming

an appearance of solidity. The uprights were in, and the brace ties

were

fastened together, so that if it alone on to blow there was no fear of

the

structure being destroyed The stores had

now to be dragged a

distance of nearly three hundred yards from the ship to the

landing-place, but

this work, was greatly facilitated by our being able to use four of the

ponies,

working two of them for an hour, and then giving these a spell whilst

two

others took their place. The snow was very deep, and the ponies sank in

well above

the knees; it was heavy going for the men who were leading them. A

large amount

of stores was landed in this way, but a new and serious situation arose

through

the breaking away of the main ice-foot. On the previous

day an

ominous-looking crack had been observed to be developing at the end of

the

ice-foot nearest to Flagstaff Point, and it became apparent that if

this crack

continued to widen, it would cut right across the centre of our stores,

with

the result that, unless removed, they would be irretrievably lost in

the sea.

Next day (the 10th) there was no further opening of the crack, but at

seven

o'clock that night another crack formed on the ice-foot inside of

Derrick Point

where we were now landing stores. There was no immediate danger to be

apprehended

at this place, for the bay ice would have to go out before the ice-foot

could

fall into the sea. Prudence suggested that it would be better to shift

the

stores already landed to a safer place before discharging any more from

the

ship, so at 8 P.M. on the 10th we commenced getting the remainder of

the wood

for the hut and the bales of cork for the lining up on to the bare

land. This

took till about midnight, when we knocked off for cocoa and a sleep. We turned to at

six o'clock next

morning, and I decided to get the stores up the cliff face at Derrick

Point

before dealing with those at Front Door Bay, the first landing-place,

for the

former ice-foot seemed in the greater peril of collapse than did the

latter.

Adams, Joyce, and Wild soon rigged up a boom and tackle from the top of

the

cliff, making the heel of the boom fast by placing great blocks of

volcanic

rocks on it. A party remained below on the ice-foot to shift and hook

on the

cases, whilst another party on top, fifty feet above, hauled away when

the word

was given from below, and on reaching the top of the cliff, the cases

were

hauled in by means of a guy-rope. The men were hauling on the thin rope

of the

tackle from eight o'clock in the morning till one o'clock the following

morning

with barely a spell for a bit to eat. We now had to

find another and safer

place on which to land the rest of the coal and stores. Further round

the bay

from where the ship was lying was a smaller bight where a gentle slope

led on

to bare rocks, and Back Door Bay, as we named this place, became our

new depot.

The ponies were led down the hill, and from Back Door Bay to the ship.

This was

a still longer journey than from Derrick Point, but there was no help

for it,

and we started landing the coal, after laying a tarpauling on the rocks

to keep

the coal from becoming mixed with the earth. By this time there were

several

ugly looking cracks in the bay ice, and these kept opening and closing,

having

a play of seven or eight inches between the floes. We improvised

bridges out of

the bottom and sides of the motor-ear case so that the ponies could

cross the

cracks, and by eleven o'clock were well under way with the work. Mackay

had

just taken ashore a load with a pony, Armytage was about to hook on

another

pony to a loaded sledge at the ship, and a third pony was standing tied

to our

stern anchor rope waiting its turn for sledging, when suddenly, without

the

slightest warning, the greater part of the bay ice opened out into

floes, and

the whole mass that had opened started to drift slowly out to sea. The

ponies

on the ice were now in a perilous position. The sailors rushed to

loosen the

one tied to the stern rope, and got it over the first crack, and

Armytage also

got the pony he was looking after off the floe nearest the ship on to

the next

floe. Just at that moment Mackay appeared round the corner from Back

Door Bay

with a third pony attached to an empty sledge, on his way back to the

ship to

load up. Orders were shouted to him not to come any further, but he did

not at

first grasp the situation, for he continued advancing over the ice,

which was

now breaking away more rapidly. The party working on the top of Derrick

Point,

by shouting and waving, made him realise what had occurred. He

accordingly left

his sledge and pony and rushed over towards where the other two ponies

were

adrift on the ice, and, by jumping the widening cracks, he reached the

moving

floe on which they were standing. This piece of ice gradually drew

closer to a

larger piece, from which the animals would be able to gain a place of

safety.

Mackay started to try and get the pony Chinaman across the crack when

it was

only about six inches wide, but the animal suddenly took fright, reared

up on

his hind legs, and backing towards the edge of the floe, which had at

that

moment opened to a width of a few feet, fell bodily into the ice-cold

water. It

looked as if it was all over with poor Chinaman, but Mackay hung on to

the head

rope, and Davis, Mawson, Michell and one of the sailors who were on the

ice

close by rushed to his assistance. The pony managed to get his fore

feet on to

the edge of the ice-floe. After great difficulty a rope fling was

passed

underneath him, and then by tremendous exertion he was lifted up far

enough to

enable him to scramble on to the ice. There he stood, wet and trembling

in

every limb. A few seconds later the floe closed up against the other

one. It

was providential that it had not done so during the time that the pony

was in

the water, for in that case the animal would inevitably have been

squeezed to

death between the two huge masses of ice. A bottle of brandy was thrown

on to

the ice from the ship, and half its contents were poured down

Chinaman's

throat. The ship was now turning round with the object of going bow on

to the

floe, in order to push it ashore, so that the ponies might cross on to

the fast

ice, and presently, with the engine at full speed, the floe was slowly

but

surely moved back against the fast ice. Directly the floe was hard up

against

the unbroken ice, the ponies were rushed across and taken straight

ashore, and

the men who were on the different floes took advantage of the temporary

closing

of the crack to get themselves and the stores into safety. I decided,

after

this narrow escape, not to risk the ponies on the sea ice again. The

ship was

now backed out, and the loose floes began to drift away to the west.

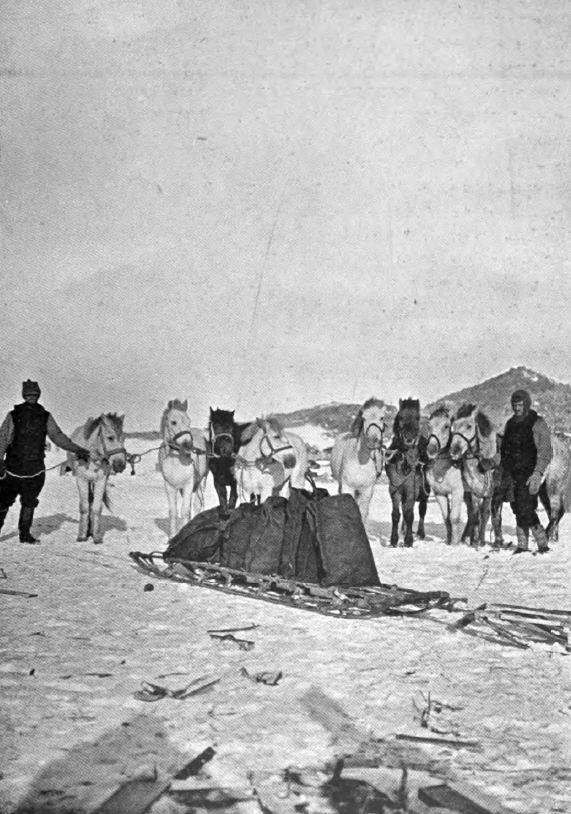

THE PONIES

TRANSPORTING COAL ON SLEDGES AT By 1 P.M. most

of the ice had

cleared out, and the ship came in to the edge of the fast ice, which

was now

abreast of Back Door Bay. Hardly were the ice-anchors made fast before

new

cracks appeared, and within a quarter of an hour the ship was adrift

again. As

it was impossible to discharge under these conditions, the Nimrod

stood off. We had now practically

the whole of the wintering

party ashore, so when lunch was over, the main party went on with the

work at

Derrick Point, refreshed by the hot tea and meat, which they had

hastily

swallowed. I organised

that afternoon a small

party to shift the main stores into safety. We had not been long at

work before

I saw that it would need the utmost despatch and our most strenuous

endeavours

to save the valuable cases; for the crack previously observed opened

more each

hour. Perspiration poured down our faces and bodies as we toiled in the

hot

sun. After two hours' work we had shifted into a place of safety all

our cases

of scientific instruments, and a large quantity of fodder, and hardly

were they

secured than, with a sharp crack, the very place where they had been

lying fell

with a crash into the sea. Had we lost these cases the result would

have been

very serious, for a great part of our scientific work could not have

been

carried out, and if the fodder had been lost, it would have meant the

loss of

the ponies also. The breaking of this part of the ice made us redouble

our

efforts to save the rest of the stores, for we could not tell when the

next

piece of ice might break off, though no crack was yet visible. The

breaking up

of the bay ice that morning turned out to be after all for the best,

for I

would not otherwise have gone on so early with this work. I ran up the

hill to

the top of Flagstaff Point to call the ship in, in order to obtain

additional

help from the crew; she had been dodging about outside of the point

since one

o'clock, but she was beyond hailing distance, and it was not till about

seven

o'clock that I saw her coming close in again. I at once hailed England

and told

him to send every available man ashore immediately. In a few minutes a

boat

came off with half a dozen men, and I sent a message back by the

officer in

charge for mere members of the ship's crew to be landed at once, and

only

enough men left on board to steer the ship and work the engines. I had

previously knocked off the party working on the hut, and with the extra

assistance

we "smacked things about" in a lively fashion. The ice kept breaking

off in chunks, but we had the satisfaction of seeing every single

package safe

on the rocks by midnight. Our party then

proceeded to sledge

the heavier cases and the tins of oil at the foot of Derrick Point

round the

narrow causeway of ice between the perpendicular rocks and the sea to

the depot

at Back Door Bay. I was astonished and delighted on arriving at the

derrick to

find the immense amount of stores that had been placed in safety by the

efforts

of the Derrick Point party, and by 1 A.M. on February 13 all the stores

landed

were in safety. About a ton of flour in cases remained to be hauled up,

but as

we already had enough ashore to last us for a year, and knowing that at

Hut

Point there were large quantities of biscuit left by the last

expedition, which

would be available if needed, we just rolled the cases on the ice-foot

into a

hollow at the foot of the cliff, where they were in comparative safety,

as the

ice there would not be likely to break away immediately. We retrieved

these

after the ship left. When making

arrangements for the

necessary equipment of the expedition, I tried to get the bulk of the

stores

into cases of uniform size and weight, averaging fifty to sixty pounds

gross,

and thus allow of more easy handling than would have been the case if

the

stores were packed in the usual way. The goods packed in Venesta cifses

could

withstand the roughest treatment without breakage or damage to the

contents.

These Venesta cases are made of three thin layers of wood, fastened

together by

a patent process; the material is much tougher than ordinary wood,

weighs much

less than a case of the same size made of the usual deal, and being

thinner,

takes up much less room, a consideration of great moment to a Polar

expedition.

The wood could not be broken by the direct blow of a heavy hammer, and

the

empty cases could be used for the making of the hundred and one odds

and ends

that have to be contrived to meet requirements in such an expedition as

this. At 1 P.M. on

the morning of February

13 I signalled the ship to come in and take off the crew, and a boat

was sent

ashore. There was a slight breeze blowing, and it took them some time

to pull

off to the Nimrod, which lay a long

way out. We on shore turned in, and we were so tired that it was noon

before we

woke up. A glance out to sea showed that we had lost nothing by our

sleep, for

there was a heavy swell running into the bay and it would have been

quite impossible

to have landed any stores at all. In the afternoon the ship came in

fairly

close, but I signalled England that it was useless to send the boat.

This

northerly swell, which we could hear thundering on the ice-foot, would

have

been welcome a fortnight before, for it would have broken up a large

amount of

fast ice to the south, and I could not help imagining that probably at

this

date there was open water up to Hut Point. Now, however, it was the

worst thing

possible for us, as the precious time was slipping by, and the still

more

valuable coal was being used up by the continual working of the ship's

engines.

Next day the swell still continued, so at 4 P.M. I signalled England to

proceed

to Glacier Tongue and land a depot there. Glacier Tongue is a

remarkable

formation of ice which stretches out into the sea from the south-west

slopes of

Mount Erebus. About five miles in length, running east and west,

tapering

almost to a point at its seaward end, and having a width of about a

mile where

it descends from the land, cracked and crevassed all over and floating

in deep

water, it is a phenomenon which still remains a mystery. It lies about

eight

miles to the northward of Hut Point, and about thirteen to the

southward of

Cape Royds, and I thought this would be a good place at which to land a

quantity of sledging stores, as by doing so we would be saved haulage

at least

thirteen miles, the distance between the spot on the southern route and

Cape

Royds. The ship arrived there in the early evening, and landed the

depot on the

north side of the Tongue. The Professor took bearings so that there

might be no

difficulty in finding the depot when the sledging season commenced. The

sounding at this spot gave a depth of 157 fathoms. From the seaward end

of the

glacier it was observed that the ice had broken away only a couple of

miles

further south, so the northerly swell had not been as far-reaching in

its

effect as I had imagined. The ship moored at the Tongue for the night. During this day

we, ashore at Cape

Royds, were variously employed; one party continued the building of the

hut,

whilst the rest of us made a more elaborate temporary dwelling and

cook-house

than we had had up to that time. The walls were constructed of bales of

fodder,

which lent themselves admirably for this purpose, the cook-tent

tarpauling was

stretched over these for a roof and was supported on planks, and the

outer

walls were stayed with uprights from the pony-stalls. As the roof was

rather

low and people could not stand upright, a trench was dug at one end,

where the

cook could move about without bending his back the whole time. In this

corner

were concocted the most delicious dishes that ever a hungry man could

wish for.

Wild acted as cook till Roberts came ashore permanently, and it was a

sight to

see us in the dim light that penetrated through the door of the fodder

hut as

we sat in a row on cases, each armed with a spoon manufactured out of

tin and

wood by the ever-inventive Day, awaiting with eagerness our bowl of

steaming

hoosh or rich dark-coloured penguin breast, followed by biscuit, butter

and jam;

tea and smokes ended up the meal, and, as we lazily stretched ourselves

out for

the smoke, regardless of a temperature of 16 or 18 degrees of frost, we

felt

that things were not so bad. The same day

that we built the

fodder hut we placed inside it some cases of bottled fruit, hoping to

save them

from being cracked by the severe frost outside. The bulk of the cases

containing liquid we kept on board the ship till the last moment so

that they could

be put into the main hut when tho fire was lighted. We turned in about

midnight, and got up at seven next morning. The ship had just come

straight in,

and I went off on board. Marshall also came off to attend to

Mackintosh, whose

wound was rapidly healing. He was now up and about. He was very

anxious to stay with us,

but Marshall did not think it advisable for him to risk it. During the

whole of

this day and the next, the 15th, the swell was too great to admit of

any stores

being landed, but early on the morning of the 16th we found it possible

to get

ashore at a small ice-foot to the north of Flagstaff Point, and here,

in spite

of the swell, we managed to land six boatloads of fruit, some oil, and

twenty-four bags of coal. The crew of the boat, whilst the stores were

being

taken out, had to keep to their oars, and whenever the swell rolled on

the

shelving beach, they had to back with all their might to keep the bow

of the

boat from running under the overhanging ice-foot and being crushed

under the

ice by the lifting wave. Davis, the chief officer of the Nimrod,

worked like a Titan. A tall, red-headed Irishman, typical

of his country, he was always working and always cheerful, having no

time-limit

for his work. He and Harbord, the second officer, a quiet, self-reliant

man,

were great acquisitions to the expedition. These two officers were ably

supported by the efforts of the crew. They had nothing but hard work

and

discomfort from the beginning of the voyage, and yet they were always

cheerful,

and worked splendidly. Dunlop, the chief engineer, not only kept his

department

going smoothly on board but was the principal constructor of the hut. A

great

deal of the credit for the work being so cheerfully performed was due

to the

example of Cheetham, who was an old hand in the Antarctic, having been

boatswain of the Morning on both the voyages she made for the relief of

the Discovery. He was third mate

and

boatswain on this expedition. When I had gone

on board the

previous day I found that England was still poorly and that he was

feeling the

strain of the situation. He was naturally very anxious to get the ship

away and

concerned about the shrinkage of the coal-supply. I also would have

been glad

to have seen the Nimrod on her way

north, but it was impossible to let her leave until the wintering party

had

received their coal from her. In view of the voyage home, the ship's

main

topmast was struck to lessen her rolling in bad weather. It was

impossible to

ballast the ship with rock, as the time needed for this operation would

involve

the consumption of much valuable coal, and I was sure that the heavy

iron-bark

and oak hull, and the weight of the engine and boiler filled with

water, would

be sufficient to ensure the ship's safety. We found it

impossible to continue working

at Cliff Point later on in the day, so the ship stood off whilst those

on shore

went on with the building of the hut. Some of the shore-party had come

off in

the last boat to finish writing their final letters home, and during

the night

we lay to waiting for the swell to decrease. The weather was quite

fine, and if

it had not been for the swell we could have got through a great deal of

work.

February is by no means a fine month in the latitude we were in, and up

till

now we had been extremely fortunate, as we had not experienced a real

blizzard. The following

morning, Monday,

February 17, the sea was breaking heavily on the ice-foot at the bottom

of

Cliff Point. The stores that had been landed the previous day had been

hoisted

up the overhanging cliff and now formed the fourth of our scattered

depots of

coal and stores. The swell did not seem so heavy in Front Door Bay, so

we

commenced landing the stores in the whale-boat at the place where the

ice-foot

had broken away, a party on shore hauling the bags of coal and the

cases up the

ice-face, which was about fourteen feet high. The penguins were still

round us

in large numbers. We had not had any time to make observations on them,

being

so busily employed discharging the ship, but just at this particular

time our

attention was called to a couple of these birds which suddenly made a

spring

from the water and landed on their feet on the ice-edge, having cleared

a

vertical height of twelve feet. It seemed a marvellous jump for these

small

creatures to have n.ade, and shows the rapidity with which they must

move

through water to gain the impetus that enables them to clear a distance

in

vertical height four times greater than their own, and also how

unerring must

be their judgment in estimation of the distance and height when

performing this

feat. The work of landing stores at this spot was greatly hampered by

the fact

that the bay was more or less filled with broken floes, through which

the boat

had to be forced. It was impossible to use the oars in the usual way,

so, on

arriving at the broken ice, they were employed as poles. The bow of the

boat

was entered into a likely looking channel, and then the crew, standing

up,

pushed the boat forward by means of the oars, the ice generally giving

way on

each side, but sometimes closing up and nipping the boat, which, if it

had been

less strongly built, would assuredly have been crushed. The Professor,

Mawson,

Cotton, Michell and a couple of seamen formed the boat's crew, and with

Davis

or Harbord in the stern, they dodged the ice very well, considering the

fact

that the swell was rather heavy at the outside edge of the floes. When

along-side the ice-foot one of the crew hung on to a rope in the bow,

-and

another did the same in the stern, hauling in the slack as the boat

rose on top

of the swell, and easing out as the water swirled downwards from the

ice-foot.

There was a sharp-pointed rock, which, when the swell receded, was

almost above

water, and the greatest difficulty was experienced in preventing the

boat from

crashing down on the top of this. The rest of the staff in the boat and

on

shore hauled up the cases and bags of coal at every available

opportunity. The

coal was weighed at the top of the ice-foot, and the bags emptied on to

a heap

which formed the main supply for the winter months. We had now three

depots of

coal in different places round the winter quarters. In the afternoon

the

floating ice at this place became impassable, but fortunately it had

worked its

way out of Back Door Bay, where, in spite of the heavy swell running

against

the ice-foot, we were able to continue adding to the heap of coal until

nearly

eight tons had been landed. It was a dull and weary job except when

unpleasantly enlivened by the imminent danger of the boat being caught

between

heavy pieces of floating ice and the solid ice-foot. These masses of

ice rose

and fell on the swell, the water swirling round them as they became

submerged,

and pouring off their tops and sides as they rose to the surface. It

required

all Harbord's watchfulness and speediness of action to prevent damage

to the

boat. It is almost needless to observe that all hands were as grimy as

coal-heavers, especially the boat's crew, who were working in the

half-frozen

slushy coal-dust and sea spray. The Professor, Mawson, Cotton, and

Michell

still formed part of the crew. They had, by midnight, been over twelve

hours in

the boat, excepting for about ten minutes' spell for lunch, and after

discharging each time had a long pull back to the ship. When each

boat-load was

landed, the coal and stores had to be hauled up on a sledge over a very

steep

gradient to a place of safety, and after this was accomplished, there

was a

long wait for the next consignment. Work was

continued all night, though

every one was nearly dropping with fatigue; but I decided that the boat

returning to the ship at 5 A.M. (the 18th) should take a message to

England

that the men were to knock off for breakfast and turn to at 7 A.M.

Meanwhile

Roberts had brewed some hot coffee in the hut, where we now had the

stove

going, and, after a drink of this, our weary people threw themselves

down on

the sleeping-bags in order to snatch a short rest before again taking

up the

work. At 7 A.M. I went to the

top of Flagstaff

Point, but instead of seeing the ship close in, I spied her hull down

on the

horizon, and could see no sign of her approaching the winter quarters

to resume

discharging. After watching her for about half an hour, I returned to

the hut,

woke up those of the staff who from utter weariness had dropped asleep,

and

told them to turn into their bags and have a proper rest. I could not

imagine

why the ship was not at hand, but at a quarter to eleven Harbord came

ashore

and said that England wanted to see me on board; so, leaving the others

to

sleep, I went off to the Nimrod. On

asking England why the ship was not in at seven to continue

discharging, he

told me that all hands were so dead-tired that he thought it best to

let them

have a sleep. The men were certainly worn out. Davis' head had dropped

on the

wardroom table, and he had gone sound asleep with his spoon in his

mouth, to

which he had just conveyed some of his breakfast. Cotton had fallen

asleep on

the platform of the engine-room steps, whilst Mawson, whose lair was a

little

store-room in the engine-room, was asleep on the floor. His long legs,

protruding through the doorway, had found a resting-place on the

cross-head of

the engine, and his dreams were mingled with a curious rhythmical

motion which

was fully accounted for when he woke up, for the ship having got under

way, the

up-and-down motion of the piston had moved his limbs with every stroke.

The

sailors also were fast asleep; so, in the face of this evidence of

absolute

exhaustion, I decided not to start work again till after one o'clock,

and told

England definitely that when the ship had been reduced in coal to

ninety-two

tons as a minimum I would send her north. According to cur experiences

on the

last expedition, the latest date to which it would be safe to keep the Nimrod would be the end of February, for

the young ice forming about that time on the sound would seriously

hamper her

getting clear of the Ross Sea. Later observations of the ice conditions

of

McMurdo Sound at our winter quarters showed us that a powerfully

engined ship

could have gone north later in the year, perhaps even in the winter,

for we had

open water close to us all the time. About 2 P.M.

the Nimrod came close in to

Flagstaff Point

to start discharging again. I decided that it was time to land the more

delicate instruments, such as watches, chronometers, and all personal

gear. The

members of the staff who were on board hauled their things out of

Oyster Alley,

and, laden with its valuable freight, we took the whale-boat into Front

Door

Bay. Those who had

been ashore now went

on board to collect their goods and finish their correspondence. During

the

afternoon we continued boating coal to Front Door Bay, which was again

free of

ice, and devoted our attention almost entirely to this work. About five

o'clock on the afternoon

of February 18, snow began to fall, with a light wind from the north,

and as at

times the boat could hardly be seen from the ship, instructions were

given to

the boat's crew that whenever the Nimrod

was not clearly visible they were to wait alongside the shore until the

snow

squall had passed and she appeared in sight again. At six o'clock, just

as the

boat had come alongside for another load, the wind suddenly shifted to

the

south-east and freshened immediately. The whaler was hoisted at once,

and the Nimrod stood off from the

shore, passing

between some heavy ice-floes, against one of which her propeller

struck, but

fortunately without sustaining any damage. Within half an hour it was

blowing a

furious blizzard, and every sign of land, both east and west, was

obscured in

the scudding drift. I was aboard the vessel at the time. We were then

making

for the fast-ice to the south, but the Nimrod

was gaining but little headway against the terrific wind and

short-rising sea; so

to save coal I decided to keep the engines just going slow and maintain

our

position in the sound as far as we could judge, though it was

inevitable that

we should drift northward to a certain extent. All night the gale raged

with

great fury. The speed of the gusts at times must have approached a

force of a

hundred miles an hour. The tops of the seas were cut off by the wind,

and flung

over the decks, mast, and rigging of the ship, congealing at once into

hard

ice, and the sides of the vessel were thick with the frozen sea water.

"The

masts were grey with the frozen spray, and the bows were a coat of

mail."

Very soon the cases and sledges lying on deck were hard and fast in a

sheet of

solid ice, and the temperature had dropped below zero. Harbord, who was

the

officer on watch, on whistling to call the crew aft, found that the

metal

whistle stuck to his lips, a painful intimation of the low temperature.

I spent

most of the night on the bridge, and hoped that the violence of the

gale would

be of but short duration. This hope was not realised, for next morning,

February 19, at 8 A.M., it was blowing harder than ever. During the

early hours

of the day the temperature was minus 16° Fahr., and consistently kept

below

minus 12° Fahr. The motion of the ship was sharp and jerky, yet,

considering

the nature of the sea and the trim of the vessel, she was remarkably

steady. To

a certain extent this was due to the fact that the main topmast had

been

lowered. We had constantly to have two men at the wheel, for the

rudder, being

so far out of the water, received the blows of the sea as they struck

the

quarter and stern; and the steersman having once been flung right over

the

steering-chains against the side of the ship, it was necessary to have

two

always holding on to the kicking wheel. At times there would be a

slight lull,

the seas striking less frequently against the rudder, and the result

would be

that the rudder-well soon got filled with ice, and it was found

impossible to

move the wheel at all. To overcome this dangerous state of things the

steersmen

had to keep moving the wheel alternately to port and starboard, after

the ice

had been broken away from the well. In spite of this precaution, the

rudder-well occasionally became choked, and one of the crew, armed with

a long

iron bar, had to stand by continually to break the frozen sea water off

the

rudder. In the blinding drift it was impossible to see more than a few

yards

from the ship, and once a large iceberg suddenly loomed out of the

drift close

to the weather bow of the Nimrod;

fortunately

the rudder had just been cleared, and the ship answered her helm, thus

avoiding

a collision. All day on the

20th, through the

night, and throughout the day and night of the 21st, the gale raged.

Occasionally the drift ceased, and we saw dimly bare rocks, sometimes

to the

east and sometimes to the west, but the upper parts of them being

enveloped in

snow clouds, it was impossible to ascertain exactly what our position

was. At

these times we were forced to wear ship; that is, to turn the ship

round,

bringing the wind first astern and then on to the other side, so that

we could

head in the opposite direction. It was impossible in face of the storm

to tack,

i.e. to turn the ship's head into the wind, and round, so as to bring

the wind

on the other side. About midnight on the 21st, whilst carrying out this

evolution of wearing ship, during which the Nimrod

always rolled heavily in the trough of the waves, she shipped a heavy

sea, and,

all the release-water ports and scupper holes being blocked with ice,

the water

had no means of exit, and began to freeze on deck, where, already,

there was a

layer of ice over a foot in thickness. Any more weight like this would

have

made the ship unmanageable. The ropes, already covered with ice, would

have

been frozen into a solid mass, so we were forced to take the drastic

step of

breaking holes in the bulwarks to allow the water to escape. This had

been done

already in the forward end of the ship by the gales we experienced on

our

passage down to the ice, but as the greater part of the weight in the

holds was

aft, the water collected towards the middle and stern, and the job of

breaking

through the bulwarks was a tougher one than we had imagined; it was

only by

dint of great exertions that Davis and Harbord accomplished it. It was

a sight

to see Harbord, held by his legs, hanging over the starboard side of

the Nimrod, and wielding a heavy

axe, whilst

Davis, whose length of limb enabled him to lean over without being

held, did

the same on the other side. The temperature at this time was several

degrees

below zero. Occasionally on this night, as we approached the eastern

shore, the

coast of Ross Island, we noticed the sea covered with a thick

yellowish-brown

scum. This was due to the immense masses of snow blown off the mountain

sides

out to sea, and this scum, to a certain extent, prevented the tops of

the waves

from breaking. Had it not been for this unexpected protection we would

certainly have lost our starboard boat, which had been unshipped in a

sea and

was hanging in a precarious position for the time being. It was hard to

realise

that so high and so dangerous a sea could possibly have risen in the

comparatively narrow waters of McMurdo Sound. The wind was as strong as

that we

experienced in the gales that assailed us after we first left New

Zealand, but

the waves were not so huge as those which had the whole run of the

Southern

Ocean in which to gather strength before they met us. At 2 A.M. the

weather

suddenly cleared, and though the wind still blew strongly and gustily,

it was

apparent that the force of the gale had been expended. We could now see

our

position clearly. The wind and current, in spite of our efforts to keep

our

position, had driven us over thirty miles to the north, and at this

time we

were abeam of Cape Bird. The sea was rapidly decreasing in height, and

we were

able to steam for Cape Royds. We arrived

there in the early

morning, and I went ashore at Back Door Bay, after pushing the whale

boat

through pancake ice and slush, the result of the gale. Hurrying over to

the hut

I was glad to see that it was intact, and then I received full details

of the

occurrences of the last three days on shore. The report was not very

reassuring

as regards the warmth of the hut, for the inmates stated that, in spite

of the

stove being alight the whole time, no warmth was given off. Of course

the

building was really not at all complete. It had not been lined, and

there were

only makeshift protections for the windows, but what seemed a grave

matter was

the behaviour of the stove, for on the efficiency of this depended not

only our

comfort but our very existence. The shore-party had experienced a very

heavy

gale indeed. The hut had trembled and shaken the whole time, and if the

situation had not been so admirable I doubt whether there would have

been a hut

at all after the gale. A minor accident had occurred, for our fodder

hut had

failed to withstand the gale, and one of the walls had collapsed,

killing one

of Possum's pups. The roof had been demolished at the same time. On going down

to our main landing-place,

the full effect of the blizzard became apparent. There was hardly a

sign to be

seen of the greater part of our stores. At first it appeared that the

drifting

snow had covered the cases and bales and the coal, but a closer

inspection

showed that the real disappearance of our stores from view was due to

the sea.

Such was the force of the wind blowing straight on to the shore from

the south

that the spray had been flung in sheets over everything and had been

carried by

the wind for nearly a quarter of a mile inland, and consequently in

places our

precious stores lay buried to a depth of five or six feet in a mass of

frozen

sea water. The angles taken up by the huddled masses of cases and bales

had

made the surface of this mass of ice assume a most peculiar shape. We

feared

that it would take weeks of work to get the stores clear of the ice. It

was

probable also that the salt water would have damaged the fodder, and

worked its

way into cases that were not tin-lined or made of Venesta wood, and

that some

of the things would never be seen again. No one would have recognised

the

landing-place as the spot on which we had been working during the past

fortnight, so great was the change wrought by the furious storm. Our

heap of

coal had a sheet of frozen salt water over it, but this was a blessing

in

disguise, for it saved the smaller pieces of coal from being blown

away.

A BLIZZARD ON

THE

BARRIER There was no

time then to do

anything about releasing the stores from the ice; the main thing was to

get the

remainder of the coal ashore and send the ship north. We immediately

started

landing coal at the extreme edge of Front Door Bay. The rate of work

was

necessarily very slow, for the whole place was both rough and slippery

from the

newly formed ice that covered everything. Before 10 P.M. on February

22, the

final boatload of coal arrived. We calculated that we had in all only

about

eighteen tons, so that the strictest economy would be required to make

this

amount spin out until the sledging commenced in the following spring. I

should

certainly have liked more coal, but the delays that had occurred in

finding

winter quarters, and the difficulties encountered in landing the

stores, had

caused the Nimrod to be kept longer

than I had intended already. We gave our final letters and messages to

the crew

of the last boat, and said good-bye. Cotton, who had come south just

for the

trip, was among them, and never had we a more willing worker. At 10

P.M. the Nimrod's bows were pointed

to the north,

and she was moving rapidly away from the winter quarters with a fair

wind.

Within a month I hoped she would be safe in New Zealand, and her crew

enjoying

a well-earned rest. We were all devoutly thankful that the landing of

the

stores had been finished at last, and that the state of the sea would

no longer

be a factor in our work, but it was with something of a pang that we

severed

our last connection with the world of men. We could hope for no word of

news

from civilisation until the Nimrod

came south again in the following summer, and before that we had a good

deal of

difficult work to do, and some risks to face. There was scant

time for reflection,

even if we had been moved that way. We turned in for a good night's

rest as

soon as possible after the departure of the ship, and the following

morning we

started digging the stores out of the ice, and transporting everything

to the

vicinity of the hut. It was necessary that the stores should be close

by the

building, partly in order that there might be no difficulty in getting

what

goods we wanted during the winter, and partly because we would require

all the

protection that we could get from the cold, and the cases, when piled

round our

little dwelling, would serve to keep off the wind. We hoped, as soon as

the

stores had all been placed in position, to make a start with the

scientific

observations that were to be an important part of the work of the

expedition. |