| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

THE SIXTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD THE SAILOR

AFTER

being shipwrecked five times, and escaping so many dangers, could I

resolve

again to try my fortune, and expose myself to new hardships? I am

astonished at

it myself when I think of it, and must certainly have been induced to

it by my

stars. But be that as it will, after a year's rest I prepared for a

sixth voyage,

notwithstanding the entreaties of my kindred and friends, who did all

that was

possible to prevent me. Instead of taking my way by the Persian Gulf, I

travelled once more through several provinces of Persia and the Indies,

and

arrived at a sea-port, where I embarked on board a ship, the captain of

which

was resolved on a long voyage. It was

very long indeed, but at the same time so unfortunate that the captain

and

pilot lost their course, and knew not where they were. They found it at

last,

but we had no reason to rejoice at it. We were all seized with

extraordinary

fear when we saw the captain quit his post, and cry out. He threw off

his

turban, pulled his beard, and beat his head like a madman. We asked him

the

reason, and he answered that he was in the most dangerous place in all

the sea.

"A rapid current carries the ship along with it," he said, "and

we shall all of us perish in less than a quarter of an hour. Pray to

God to

deliver us from this danger; we cannot escape it if He does not take

pity on

us." At these words he ordered the sails to be changed; but all the

ropes

broke, and the ship, without its being possible to help it, was carried

by the

current to the foot of an inaccessible mountain, where she ran ashore,

and was

broken to pieces, yet so that we saved our lives, our provisions, and

the best

of our goods. This

being over, the captain said to us, "God has done what pleased Him; we

may

every man dig our grave here, and bid the world adieu, for we are all

in so

fatal a place that none shipwrecked here have ever returned to their

homes

again." His discourse afflicted us sorely, and we embraced each other

with

tears in our eyes, bewailing our deplorable lot. The

mountain at the foot of which we were cast was the coast of a very long

and large

island. This coast was covered all over with wrecks, and from the vast

number

of men's bones we saw everywhere, and which filled us with horror, we

concluded

that abundance of people had died there. It is also impossible to tell

what a

quantity of goods and riches we found cast ashore there. All these

objects

served only to augment our grief. Whereas in all other places rivers

run from

their channels into the sea, here a great river of fresh water runs out

of the

sea into a dark cave, whose entrance is very high and large. What is

most

remarkable in this place is that the stones of the mountain are of

crystal,

rubies, or other precious stones. Here is also a sort of fountain of

pitch or

bitumen, that runs into the sea, which the fishes swallow, and then

vomit up

again, turned into ambergris; and this the waves throw up on the beach

in great

quantities. Here also grow trees, most of which are wood of aloes,

equal in

goodness to those of Comari. To

finish the description of this place, which may well be called a gulf,

since

nothing ever returns from it-it is not possible for ships to get away

again

when once they come near it. If they are driven thither by a wind from

the

sea, the wind and the current ruin them; and if they come into it when

a

land-wind blows, which might seem to favour their getting out again,

the height

of the mountain stops the wind, and occasions a calm, so that the force

of the

current runs them ashore, where they are broken to pieces, as ours was;

and

that which completes the misfortune is that there is no possibility to

get to

the top of the mountain, or to get out any manner of way. We

continued upon the shore, like men out of their senses, and expected

death

every day. At first we divided our provisions as equally as we could,

and thus

everyone lived a longer or shorter time, according to their temperance,

and the

use they made of their provisions. Those

who died first were interred by the rest; and, for my part, I paid the

last

duty to all my companions. Nor are you to wonder at this; for besides

that I

husbanded the provision that fell to my share better than they, I had

provision

of my own, which I did not share with my comrades; yet when I buried

the last,

I had so little remaining that I thought I could not hold out long: so

I dug a

grave, resolving to lie down in it, because there was none left to

inter me. I

must confess to you at the same time that while I was thus employed I

could not

but reflect upon myself as the cause of my own ruin, and repented that

I had

ever undertaken this last voyage; nor did I stop at reflections only,

but had

well nigh hastened my own death, and began to tear my hands with my

teeth. But it

pleased God once more to take compassion on me, and put it in my mind

to go to

the bank of the river which ran into the great cave; where, considering

the

river with great attention, I said to myself, "This river, which runs

thus

under ground, must come out somewhere or other. If I make a raft, and

leave

myself to the current, it will bring me to some inhabited country, or

drown me.

If I be drowned I lose nothing, but only change one kind of death for

another;

and if I get out of this fatal place, I shall not only avoid the sad

fate of my

comrades, but perhaps find some new occasion of enriching myself. Who

knows but

fortune waits, upon my getting off this dangerous shelf, to compensate

my

shipwreck with interest?" I

immediately went to work on a raft. I made it of large pieces of timber

and

cables, for I had choice of them, and tied them together so strongly

that I had

made a very solid little raft. When I had finished it I loaded it with

some

bales of rubies, emeralds, ambergris, rock-crystal, and rich stuffs.

Having

balanced all my cargo exactly and fastened it well to the raft, I went

on board

it with two little oars that I had made, and, leaving it to the course

of the

river, I resigned myself to the will of God. As soon

as I came into the cave I lost all light, and the stream carried me I

knew not

whither. Thus I floated for some days in perfect darkness, and once

found the

arch so low that it well nigh broke my head, which made me very

cautious

afterwards to avoid the like danger. All this while I ate nothing but

what was

just necessary to support nature; yet, notwithstanding this frugality,

all my

provisions were spent. Then a pleasing sleep fell upon me. I cannot

tell how

long it continued; but when I awoke, I was surprised to find myself in

the

middle of a vast country, at the bank of a river, where my raft was

tied,

amidst a great number of negroes. I got up as soon as I saw them and

saluted

them. They spoke to me, but I did not understand their language. I was

so

transported with joy that I knew not whether I was asleep or awake; but

being

persuaded that I was not asleep, I recited the following words in

Arabic aloud:

"Call upon the Almighty, he will help thee; thou needest not perplex

thyself about anything else; shut thy eyes, and while thou art asleep,

God will

change thy bad fortune into good." One of

the blacks, who understood Arabic, hearing me speak thus, came towards

me and

said, "Brother, be not surprised to see us; we are inhabitants of this

country, and came hither to-day to water our fields, by digging little

canals

from this river, which comes out of the neighbouring mountain. We saw

something

floating upon the water, went speedily to find out what it was, and

perceiving

your raft, one of us swam into the river, and brought it hither, where

we

fastened it, as you see, until you should awake. Pray tell us your

history, for

it must be extraordinary; how did you venture into this river, and

whence did

you come?" I begged

of them first to give me something to eat, and then I would satisfy

their

curiosity. They gave me several sorts of food; and when I had satisfied

my

hunger, I gave them a true account of all that had befallen me, which

they

listened to with wonder. As soon as I had finished my discourse, they

told me,

by the person who spoke Arabic and interpreted to them what I said,

that it was

one of the most surprising stories they ever heard, and that I must go

along

with them, and tell it to their king myself; the story was too

extraordinary to

be told by any other than the person to whom it happened. I told them I

was

ready to do whatever they pleased. They

immediately sent for a horse, which was brought in a little time; and

having

made me get upon him, some of them walked before me to show me the way,

and the

rest took my raft and cargo, and followed me. We

marched thus altogether, till we came to the city of Serendib, for it

was in

that island I landed. The blacks presented me to their king; I

approached his

throne, and saluted him as I used to do the kings of the Indies; that

is to

say, I prostrated myself at his feet, and kissed the earth. The prince

ordered

me to rise up, received me with an obliging air, and made me come up,

and sit

down near him. He first asked me my name, and I answered, "They call me

Sinbad the sailor, because of the many voyages I have undertaken, and I

am a

citizen of Bagdad." "But,"

replied he, "how came you into my dominions, and from whence came you

last?" I

concealed nothing from the king; I told him all that I have now told

you, and

his majesty was so surprised and charmed with it, that he commanded my

adventure to be written in letters of gold, and laid up in the archives

of his

kingdom. At last my raft was brought in, and the bales opened in his

presence:

he admired the quantity of wood of aloes and ambergris; but, above all,

the

rubies and emeralds, for he had none in his treasury that came near

them. Observing

that he looked on my jewels with pleasure, and viewed the most

remarkable among

them one after another, I fell prostrate at his feet, and took the

liberty to

say to him, "Sir,

not only my person is at your majesty's service, but the cargo of the

raft, and

I would beg of you to dispose of it as your own." He

answered me with a smile, "Sinbad, I will take care not to covet

anything

of yours, nor to take anything from you that God has given you; far

from

lessening your wealth, I design to augment it, and will not let you go

out of

my dominions without marks of my liberality." All the

answer I returned was prayers for the prosperity of this prince, and

commendations of his generosity and bounty. He charged one of his

officers to

take care of me, and ordered people to serve me at his own charge. The

officer

was very faithful in the execution of his orders, and caused all the

goods to

be carried to the lodgings provided for me. I went every day at a set

hour to

pay court to the king, and spent the rest of my time in seeing the

city, and

what was most worthy of notice. The Isle

of Serendib is situated just under the equinoctial line, so that the

days and

nights there are always of twelve hours each, and the island is eighty

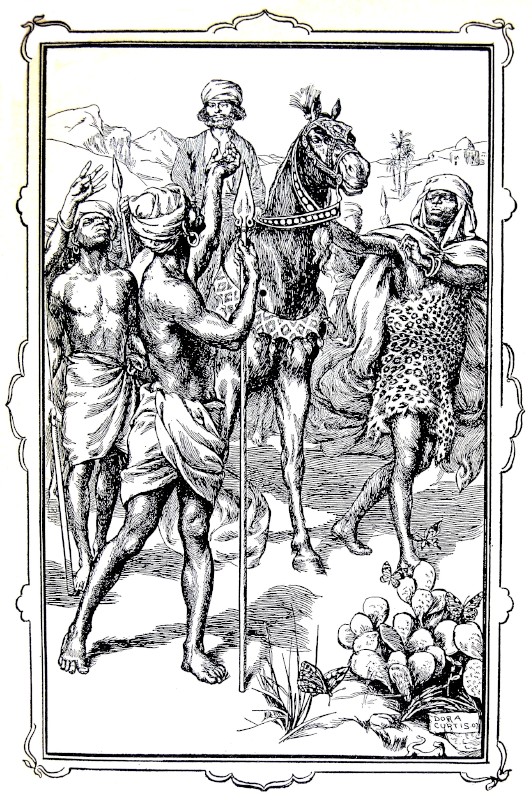

parasangs in length, and as many in breadth. The capital city stands at the end of a fine valley formed by a mountain in the middle of the island, which is the highest in the world. I made, by way of devotion, a pilgrimage to the place where Adam was confined after his banishment from Paradise, and had the curiosity to go to the top of it.  WE MARCHED THUS TOGETHER When I

came back to the city, I prayed the king to allow me to return to my

country,

which he granted me in the most obliging and honourable manner. He

would needs

force a rich present upon me, and when I went to take my leave of him,

he gave

me one much more valuable, and at the same time charged me with a

letter for

the Commander of the Faithful, our sovereign, saying to me, "I pray you

give this present from me and this letter to Caliph Haroun Alraschid,

and

assure him of my friendship." I took the present and letter in a very

respectful manner, and promised his majesty punctually to execute the

commission with which he was pleased to honour me. Before I embarked,

this

prince sent for the captain and the merchants who were to go with me,

and

ordered them to treat me with all possible respect. The

letter from the King of Serendib was written on the skin of a certain

animal of

groat value, because of its being so scarce, and of a yellowish colour.

The writing

was azure, and the contents as follows : —

"The

king of the Indies, before whom march a hundred elephants, who lives in

a

palace that shines with a hundred thousand rubies, and who has in his

treasury

twenty thousand crowns enriched with diamonds, to Caliph Haroun

Alraschid : "Though

the present we send you be inconsiderable, receive it as a brother and

a

friend, in consideration of the hearty friendship which we bear to you,

and of

which we are willing to give you proof. We desire the same part in your

friendship, considering that we believe it to be our merit, being of

the same

dignity with yourself. We conjure you this in the rank of a brother.

Farewell." The

present consisted first, of one single ruby made into a cup, about half

a foot

high, an inch thick, and filled with round pearls. Secondly, the skin

of a

serpent, whose scales were as large as an ordinary piece of gold, and

had the

virtue to preserve from sickness those who lay upon it. Thirdly, fifty

thousand

drachms of the best wood of aloes, with thirty grains of camphor as big

as

pistachios. And fourthly, a she-slave of ravishing beauty, whose

apparel was

covered all over with jewels. The ship

set sail, and after a very long and successful voyage, we landed at

Balsora;

from thence I went to Bagdad, where the first thing I did was to acquit

myself

of my commission. I took

the King of Serendib's letter, and went to present myself at the gate

of the

Commander of the Faithful, followed by the beautiful slave and such of

my own

family as carried the presents. I gave an account of the reason of my

coming,

and was immediately conducted to the throne of the caliph. I made my

reverence,

and after a short speech gave him the letter and present. When he had

read what

the King of Serendib wrote to him, he asked me if that prince were

really so

rich and potent as he had said in this letter. I prostrated myself a

second

time, and rising again, "Commander of the Faithful," said I, "I

can assure your majesty he doth not exceed the truth on that head: I am

witness

of it. There is nothing more capable of raising a man's admiration than

the

magnificence of his palace. When the prince appears in public, he has a

throne

fixed on the back of an elephant, and marches betwixt two ranks of his

ministers, favourites, and other people of his court; before him, upon

the same

elephant, an officer carries a golden lance in his hand, and behind the

throne

there is another, who stands upright with a column of gold, on the top

of which

there is an emerald half a foot long and an inch thick; before him

march a

guard of a thousand men, clad in cloth of gold and silk, and mounted on

elephants richly caparisoned. "While

the king is on his march, the officer who is before him on the same

elephant

cries from time to time, with a loud voice, Behold the great monarch,

the

potent and redoubtable Sultan of the Indies, whose palace is covered

with a

hundred thousand rubies, and who possesses twenty thousand crowns of

diamonds.'

After he has pronounced these words, the officer behind the throne

cries in his

turn, This monarch so great and so powerful, must die, must die, must

die.' And

the officer in front replies, Praise be to Him who lives for ever.' "Further,

the King of Serendib is so just that there are no judges in his

dominions. His

people have no need of them. They understand and observe justice of

themselves." The

caliph was much pleased with my discourse. "The wisdom of this king,"

said he, "appears in his letter, and after what you tell me I must

confess

that his wisdom is worthy of his people, and his people deserve so wise

a

prince." Having spoken thus he dismissed me, and sent me home with a

rich

present. |