|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

A MASSACHUSETTS SOLDIER BECOMES A GOD OF THE CHINESE

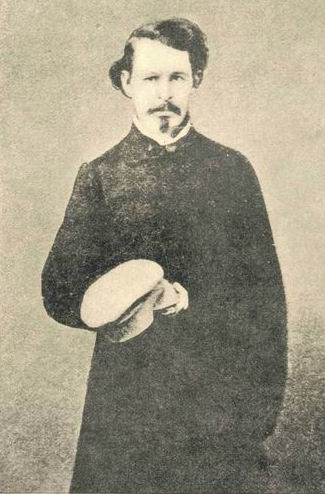

From a photograph. Collection of Peabody Museum,

Salem, Mass.

GENERAL FREDERIC TOWNSEND WARD OF SALEM.

Frederick Townsend Ward of Salem, who had served as a soldier in the Crimean War and in Nicaragua, through chance more than anything else, shipped to China as mate of an American ship and happened to arrive in Shanghai during the Tai Ping rebellion, at a time when the rebels, headed by Ching Wang, had advanced within eighteen miles of the city. He had always been of a daring disposition. It is related of him that on this voyage he plunged overboard when the ship was under full sail, in an attempt to catch an especially fine butterfly. Immediately upon his arrival he learned that a reward of two hundred thousand dollars was offered to any body of foreigners who could drive the attackers from the city of Sung-Kiang. Ward had been fond of fighting from his boyhood, and the older Salemites remember the fierce snow-ball fight between the “up-towns” and the “down-towns,” in which he led the latter to victory. With this same love of battle he promptly accepted the task, and in less than a week he raised a body of one hundred foreign soldiers and with an American named Henry Burgerine as his lieutenant set out for the seat of trouble. He approached the Tai Pings, and found that he was confronted by twelve hundred troops, so he returned to Shanghai for re-enforcements. Even now he was outnumbered one hundred to one, but so fierce was his attack that he caused great slaughter in their ranks and finally overwhelmed them. It was in this battle that the expression “foreign devils” first appeared in the Chinese vocabulary.

He received his reward and then set out against the rebels of Sung-Kiang. He and his men scaled the walls of the city and fought like demons, but were driven back. He returned for re-enforcements and succeeded in capturing the city. He then decided to move against Singpo. Notwithstanding a gallant attack the fortress stood and Ward’s troops were obliged to withdraw after a bloody fight. In this battle he was wounded five times, and it was now believed that he possessed a charmed life. Even he himself remarked continually that the bullet was not cast which was to end his life.

When he recovered from his many wounds he organized some Chinese troops, officered by Europeans and armed and equipped according to his methods, and with these soldiers he set out for Shanghai, arriving just in time to save the city from capture. His victories were numerous, and he was finally made a Mandarin of the highest degree with the title of Admiral-General. He then assumed the Chinese name of Hua, became a Chinese subject, and married a Chinese woman of high rank. He was killed in the battle of Ning-Po in 1862. Shot through the stomach he kept on exhorting his men and as victory was assured fell back unconscious into the arms of his lieutenant. He died the following day at the age of only thirty years. His funeral was a most impressive one, and was attended by Chinese, English, Americans, Germans and French, all nations having admired his discipline and bravery. Many civil and military officials accompanied his body to Sung-Kiang where he was buried in the temple grounds dedicated to Confucius thousands of years ago. Li Hung Chang wrote a memorial letter to the Emperor recording General Ward’s death and suggesting that “it is appropriate, therefore, to entreat that your Gracious Majesty do order the Board of Rites to take into consideration suitable posthumous rewards to be bestowed on him, Ward; and that both at Ning-Po and at Sung-Kiang sacrificial altars be erected to appease the Manes of this loyal man.” With promptness an Imperial Edict directed “that special temples to his memory be built at Ning-Po and Sung-Kiang. Let this case still be submitted to the Board of Rites, who will propose to Us further honors so as to show our extraordinary consideration towards him, and also that his loyal spirit may rest in peace. This from the Emperor! Respect it!” Our Minister to China, Mr. Burlingame, forwarded a full account of Ward’s career and death, which was read in the Senate and answered together with a message from President Lincoln.

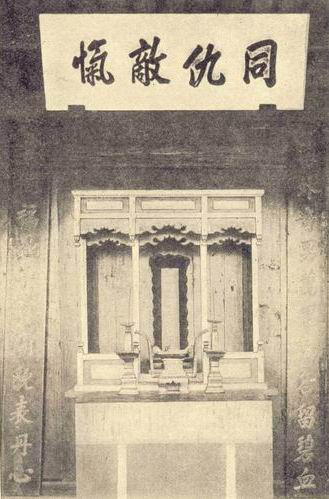

Through the lack of tact of an American attaché in Peking the Chinese Government did not carry out this Edict for fourteen years and then only at Sung-Kiang. It was Li Hung Chang who had a mausoleum erected over the graves of Ward and his wife, who died several months after her husband. The temple was dedicated on March 10, 1877 amid most impressive ceremonies. The procession moved off towards the tomb amid the banging of fire-crackers and bombs. There were sacrifices of goats, pigs, ducks, etc. then made, and at the end of the dedication there were more fireworks and gongs. Inside the temple is a shrine upon which burnt-offerings are laid in February of every New Year to the Manes of General Ward, and to which official prayers are offered every month in the year by officials of the Chinese Government. The inscription at the entrance of the shrine reads, “A wonderful hero from beyond the seas, the fame of whose deserving loyalty reaches round the world, has sprinkled China with his azure blood.” Monuments were also placed on the scenes of his victories. The mausoleum soon became a shrine supposed to be invested with miraculous power, and some years after his death he was declared to be a Joss, or God, and a manuscript to this effect can be seen in the Essex Institute in his native city, Salem. Such honors have rarely fallen to the lot of any native and never before to a man of a western nation.

The command of his Ever Victorious Army, as it was called, later fell to General Gordon, to whom has been given much credit that was really due his predecessor. A small book printed in Shanghai in 1863 records that “Not one in ten thousand . . . could at all approach him in military genius, in courage and in resources, or do anything like what he did.”

He has been criticised for being away from America during the Civil War, but it was fortune that carried him to China. He offered, however, $10,000 to the American cause, but died before the Government accepted his offer.

The Essex Institute of Salem now owns General Ward’s hat and boots as well as some of his wife’s jewelry, also the bullet that killed him, his seal, private flag, and pictures of his shrine, of himself and of his wife. Miss Elizabeth C. Ward, his sister, not long ago bequeathed $10,000 to the Essex Institute to found a Chinese library in memory of her brother, Salem’s noted warrior and Chinese god. The people of China will never forget that to Ward they probably owe the saving of Shanghai.

From a photograph. Collection of Peabody Museum, Salem, Mass.

SHRINE ERECTED IN SUNG—KIANG, CHINA, TO THE MEMORY OF GENERAL WARD.