| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER XIII AMERICAN FURNITURE MAKERS THUS

far I have made no attempt to cover one of the most interesting and

fruitful of all the industrial arts — furniture making. The

chapters on Windsor chairs and Duncan Phyfe deal with but two of the

many interesting subjects to be discovered in this field. Nor shall

I, in the present chapter, attempt anything like detailed description

or analysis, for the simple reason that an entire volume would be

required to do the subject anything like justice. Nevertheless, a

discussion of early American craftsmanship would be so glaringly

incomplete without some attention being paid to the cabinet-makers,

that I have decided upon a brief out line of the history of furniture

making in America, with apologies for its necessarily superficial

character. My purpose is not so much to impart definite information

as to indicate certain directions that further investigation well may

take. Generally speaking, we know more about English than American

furniture, and there are fascinating quarters of this field still

practically untouched.

As to the craftsmen themselves, their name is legion, and it is difficult to single out the most important or most interesting. In Colonial days every small town had its joiners and chairmakers, while in the cities the trade was a well established and generally profitable one. Judging by the examples of their work extant, many of them must have been skilled craftsmen. Unfortunately, but few of their names have been preserved, and most of those are merely names. we have no means of knowing who did some of the finest work. Among the early colonists in New England there were a number of joiners, turners, cabinet-makers, and carvers, some of whom had undoubtedly learned their trades under the best English and Dutch masters and who were capable of reproducing the styles of the day in native woods. Many of them settled in and about Boston and worked at their trade during the last three quarters of the seventeenth century. In 1642 there were twenty joiners and over thirty turners in Boston. In 1690 the Handicrafts Guild of that city had registered more than sixty furniture makers and over forty upholsterers. Miss Singleton gives the names of about forty members of the craft who were at work in Boston between 1635 and 1700. She gives the names also of furniture makers in Salem, Charlestown, and Newbury, Massachusetts, and eight in Maine. The earliest name on record appears to be that of Phineas Pratt, who was at work in Weymouth, Massachusetts, as early as 1622, while Kinelm Wynslow was prominent in Plymouth Colony prior to 1634. In Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas, practically all the furniture was imported during the seventeenth century. New York and Philadelphia had their local joiners but seem to have preferred the imported furniture. Most of the American-made furniture of the seventeenth century, therefore, was of New England origin. While the Colonial joiners, like their fellow crafts men abroad, employed oak and walnut for their finest work, they were also willing to make use of such native woods as came easily to hand — ash, elm, maple, pine, and cedar — frequently painting the softer woods. Their work was chiefly to order, or "bespoke." In these materials they produced the current English styles of the period as well as local adaptations and variations of those styles. The chairs they made were chiefly of four types — a few carved or paneled wainscot chairs, solid turned chairs, leather and "Turkey-work" chairs of the Cromwellian type, and the earlier forms of the slat-back chair. Such cane-and-walnut chairs of the Restoration period as are to be found in this country were imported. Solid, high-backed settles, gate-leg tables, desks and Bible-boxes, chests, cupboards, etc., were all made in this country in the contemporary styles. By 1700 we find the industry well established in various parts of the country. Boston continued to be the principal center, with Philadelphia a close second toward the end of the eighteenth century. Miss Singleton gives the names of a score of cabinet-makers, joiners, and chairmakers at work in Boston between 1707 and 1773. The Boston Directory of 1789 records the names of thirty-three engaged in various branches of the business, and that of 1796 some forty-five firms and individuals. Miss Singleton also found over fifty joiners, cabinet-makers, and chairmakers at work between 1703 and 1780 in Lynn, Ipswich, Marblehead, Salem, Newbury, Beverly, Gloucester, and neighboring towns. After the Revolution Samuel Phippen of Salem, who died in 1798, was a well known manufacturer.

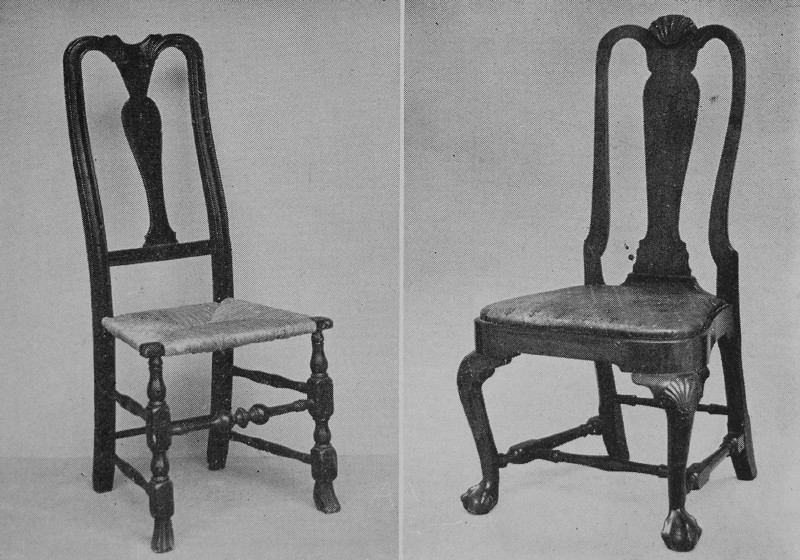

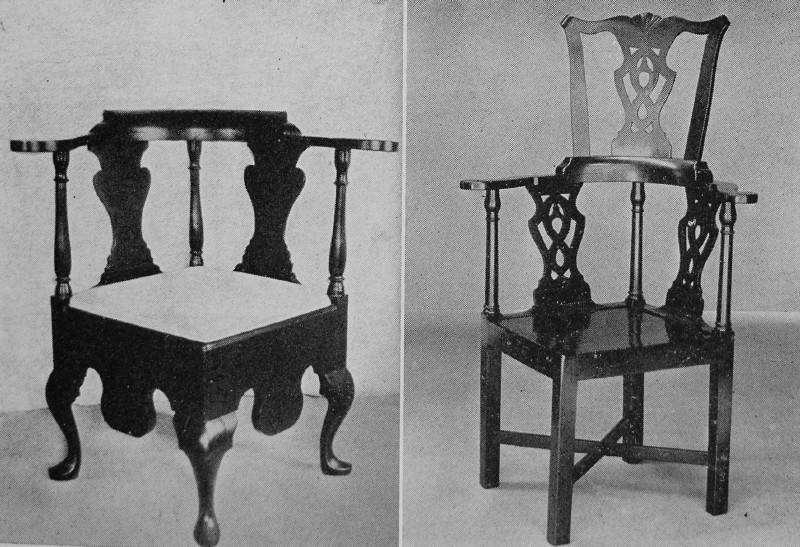

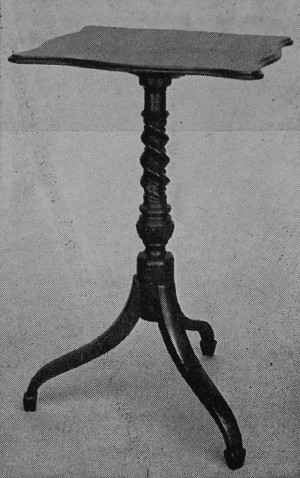

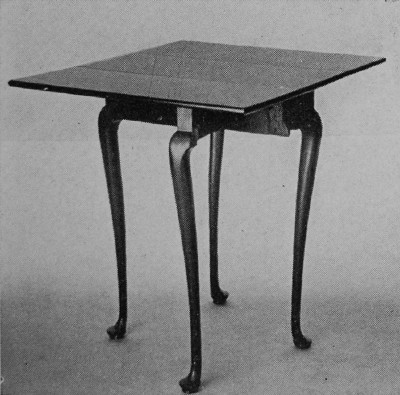

During this period the finest furniture was either imported from England or made especially to order for the homes of the well-to-do, but the Massachusetts manufacturers turned Out a large quantity of stock patterns which were not only used locally but were shipped south. Newport homes contained some fine furniture, but for the most part Connecticut and Rhode Island used furniture of local manufacture, made chiefly of cherry, cedar, whitewood, and black walnut, slat-back chairs being the commonest type until the Windsors came into vogue. Very little mahogany was used by the Connecticut makers. In New York furniture makers became more numerous after the middle of the century. For the more fashionable trade they used black walnut, wild cherry, curled maple, sweet gum, white cedar, and mahogany. New York imported considerable cedar from Bermuda and the Barbadoes and mahogany from the West Indies. Among the New York furniture makers Miss Singleton found the following: John Tremain, 1751; Robert Wallace, Beaver and New Streets, 1753; Solomon Hays, Beaver and Broad Streets, 1754; Henry Hardcastle, Burling Slip, 1755; John Brinner, Broadway, 1762; Gilbert Ash, Wall Street, 1759. The New York Directory of 1786 gives the names of only half a dozen, but that of 1789 records nineteen cabinet-makers and nineteen chairmakers. During the first half of the century Philadelphia had several upholsterers and importing houses, but few cabinet-makers. After 1750, however, several furniture makers advertised in Philadelphia papers. In 1785 Philadelphia had over fifty furniture-making concerns beside about eighteen chairmakers. In 1796 Baltimore had twenty-six cabinet-makers and several chairmakers, and thirty-seven in 1810. Charleston in 1803 had thirty-six. The popular styles underwent several changes during the eighteenth century. From 1700 to 1725 the American furniture makers used chiefly a combination of William and Mary and Dutch styles. From 1725 to 1750 American-made furniture was chiefly along Dutch lines, with local adaptations and variations. Between 1750 and 1775 the furniture made here compared favorably with that brought from England. Mahogany became more common and our furniture makers gained a more secure footing. Dutch styles gradually gave place to early Georgian and finally Chippendale. Between 1760 and 1770 a number of American cabinet-makers reproduced the designs from Chippendale's books, with little or no variation. In Philadelphia James Gillingham and in New York James Rivington and John Brinner produced mahogany furniture of high quality in the Chippendale style. Chippendale's influence persisted longer in this country than in England, and was followed by Hepplewhite and Sheraton styles late in the century. The American chairs of the eighteenth century fall roughly into five groups: those which followed fairly closely the most popular styles in England, the roundabouts, the upholstered wing chairs, the rush-bottomed slat-back and bannister-back chairs, and the Windsors which have already been described in another chapter. The first group includes the Queen Anne and Dutch types with high backs, vase-shaped, solid splats, and cabriole legs. They were made in solid and veneered walnut and other woods and were fashionable from 1700 to 1750 and even after that. About 1750 a pierced splat and the ball-and-claw foot began to appear, to be followed soon by the Chippendale designs. Mahogany became more common, and during the Revolutionary period we find a number of Hepplewhite designs, followed, toward the close of the century, by Sheraton. From 1700 to 1750 the roundabout was a popular chair in America, and is to be found in Queen Anne, Dutch, Georgian, and turned styles, with many local variations. They were particularly in vogue about 1735-40. Some were made in the cheapest woods with rush bottoms, and some in cherry, black walnut, and mahogany, with seats covered with leather or cloth. Mahogany roundabouts in Chippendale patterns became popular about the middle of the century. More definitely American were the various types of turned and rush-bottom chairs, which, being less expensive, were more common in the average home. These were made in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania, and were of walnut, oak, hickory, cherry, maple, ash, poplar, apple, pine, and various combinations of these woods, usually painted. After 1700 the later forms of the slat-backs and bannister-backs appeared. These will be discussed more in detail later. The most interesting American-made tables of the period, perhaps, were the tripod tilt-tables, tea tables, and candle Stands, made first of walnut, cherry, and other woods, and later of mahogany. They also followed the prevailing English forms, including the pie-crust top, with some variations, chiefly along the lines of simplicity and plainness. Before 1775 the tops were mostly round or scalloped; after the Revolution the octagonal form appeared. There were also plain, heavy tables of solid mahogany, and numerous variations of the Georgian styles in card tables, dining tables, etc. Beds were largely of American make because of the difficulty of importing such large pieces. The finest ones were carved four-posters following the Georgian styles. Tent beds, with curved rods for the canopy, were also common. There were also plain four-posters and low-posters and many which were rather poor attempts to improve on the English styles. Highboys,

chests of drawers, lowboys, and dressing tables of various woods were

common from 1725 to 1750. They were chiefly of local design with

cabriole legs and other Dutch characteristics. From 1750 to 1775 high

chests of drawers, dressing tables, and desks, with elaborately

carved scroll and broken-arch pediments, were made in Philadelphia

and New York. In New England the block front was originated and was

used on low chests of drawers, bureaus, dressing tables,

chests-on-chests of drawers, desks, and secretaries.

Most of the desks and secretaries used here prior to the Revolution were probably imported, though a few old walnut ones are to be found which were undoubtedly made here, as well as later ones of mahogany. After the Revolution they were made in increasing numbers, particularly bookcase desks and secretaries. They range from the very simple to the very elaborate — some severely square and plain, and some with serpentine and block fronts and carved pediments. Mahogany veneer was the common material used. A few fine examples of low-top desks are to be found, with tambour fronts and delicate inlay, indicating Shearer or Sheraton influence, and dating about 1790. The last quarter of the eighteenth century found a large number of skilled cabinet-makers at work. of these Duncan Phyfe was the chief, but there were many others in various cities who produced fine furniture, particularly while the Sheraton influence prevailed. They seem to have caught the spirit of his delicate art to a remarkable degree. Until 1810 this influence was strong, but it gradually gave way to the Empire craze which modified all our designing and resulted in the so-called American Empire style. By 1825 this had become heavy and Ornate and but little superior to the machine-made furniture that followed. The most interesting chairs of the early nineteenth century were the definitely Sheraton types, the Phyfe productions, the late Windsors, and the "fancy" chairs. These last were made in New York in considerable quantities between 1800 and 1830 and were highly favored for both dining-room and chamber. They were light chairs of soft wood, with rush or cane seats, straight, turned legs, stiles bending slightly back, with or without arms, and with two or more horizontal slats across the back, sometimes ornamented with spindles or balls. They were usually painted black and decorated with gilt, and a yellow or gilt design of fruit or flowers was painted on the broad slat at the top of the back. Sofas were made in the same style. The "fancy" chair was introduced in New York as early as 1797 by one William Challen who came from London. In 1802 William Palmer, 2 Nassau Street, advertised black and gold "fancy" chairs with cane and rush bottoms. In 1806 William Mott, 51 Broadway, advertised similar chairs, also green, white, and gilt ones. In 1812 Asa Holden, 32 Broad Street, advertised ball and spindle back "fancy" chairs, and in 1817 Wharton & Davies introduced a line of "fancy" chairs both painted and of curled maple — side chairs, armchairs, rocking- chairs, settees, and sofas. Unpainted curled maple chairs in this style are still to be found in the vicinity of New York. Of a later period, but still of interest to collectors, are the mahogany veneered chairs of the American Empire type which were made from 1830 to 1840. They had heavy, curved backs and vase-shaped splats and were originally copied after the chair in the library of Napoleon I at Malmaison which was given by Louis Philippe to the Marquis de Marigny at New Orleans. Early nineteenth century tables included some delicate Sheraton types, but these all too soon gave place to heavy affairs with round, octagonal, or lyre- shaped pedestals and four scroll feet. Their saving grace was the occasional beauty of the veneer. The American sideboards and bureaus of the period are sought to some extent, though the later forms show the same Empire heaviness. The side boards often have three drawers, with three cup boards below, the middle one being wider and fitted with two doors. Some fine sideboards were made in the South, with serving boards and cellarettes. After 1820 a sideboard was introduced with four legs, turned feet, and turned pillars at the corners, and with one cupboard and with sometimes a butler's desk in place of the middle drawer. Desks and secretaries followed the same style tendencies as the other furniture. The French or sleigh bed which was made from 1820 to 1840 is not without interest. It had low, rolling head and foot boards and broad legs, and was usually of mahogany veneer. In addition to these more familiar types, there are one or two others that are worthy of mention. During the Washingtonian enthusiasm of 1789-90, the American eagle became a popular design motif for various purposes. Mr. R. T. Haines Halsey of New York has collected several pieces of what he calls Washington eagle furniture, made in New York, Baltimore, and Albany. One is a four-poster bedstead, carved with eagles, and the others are pieces of the Sheraton type with the eagles appearing in the form of finely inlaid medallions. This may suggest an interesting if somewhat limited field for other enterprising collectors. Contemporary

with the slip-decorated pottery of western Pennsylvania was a type of

painted furniture made by these same Germans. I do not know that any

persistent search has been made for it, and the only pieces I have

seen have been strong dower chests, painted in what were once bright

colors and bearing the bride's name or initials and often a date. My

neighbor, Mr. Renwick C. Hurry, has one painted in panels, with the

popular tulip on the central one, and the name Anna Maria Muthhart,

1786, above. The common design motifs were conventionalized flowers —

particularly the tulip — fruits, birds, etc., and were painted in

greens, reds, blues, and yellows.

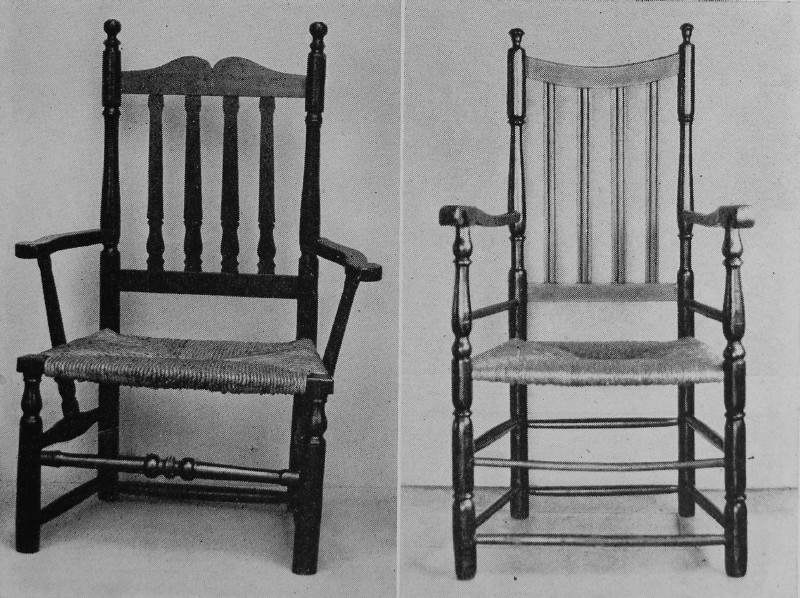

The collector, it will be seen, has a wide field to choose from in the work of American furniture makers. The Dutch and Georgian types of the eighteenth century, the later Sheraton and Phyfe furniture, the Windsor chairs, and the slat-backs and bannister-backs are all worthy of attention. The last-named group I have reserved for further consideration because I believe it offers an opportunity for American collectors that has not been fully improved, though I have not thought it advisable to devote a separate chapter to this subject. The earliest chairs made in New England had rush seats and turned legs, arms, stretchers, and stiles. The stiles, legs, and arm-posts were large and straight and the entire chair solid and not without a certain grace of proportion. The uprights were usually of ash, arms and underbraces of hickory, and the lighter turned work of ash, hickory, or birch. These turned chairs were made from 1625 to 1700 with some variations in design. Some had vertical rods in the back. One type has been called the Carver chair because similar to Governor Carver's chair in Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth. These turned chairs were the predecessors of the slat-backs and bannister-backs, which were also the artistic descendents of the old English turned chairs and the high-backed walnut-and-cane chairs of Charles II's time. The slat-back type, which had its counterpart in England, is older than the bannister-back. The first ones, in fact, appeared as early as 1650 and were contemporary with the Carver chairs. The slat-backs had turned stiles, legs, and under-braces, and high, straight backs with from two to six slightly curved horizontal slats. They were made of native hard woods, such as maple, hickory, ash, beech, etc., with two or three kinds often used in a single chair. They were well built and were strong and useful. They were made with both rush and mat seats, the last being made of the inner bark of the basswood or linden tree and sometimes of the elm. They were called flag-bottomed, mat-bottomed, reed-bottomed, and bulrush chairs, and also, in some old inventories, "basse-bottom" chairs. In New England slat-backs were usually called "three-back chairs," "four-back chairs," etc., according to the number of slats. They were made with and without arms, the armchairs being called "great chairs." The first rocking-chairs made in America were slat-backs and appeared between 1725 and 1750. Mr. Lockwood has traced an interesting style development in the slat-backs. The first ones had three slats which were straight across top and bottom, but cut down in quarter circles at the ends. Gradually the slats grew lighter, and between 1675 and 1700 were usually curved on the top side and straight or nearly straight across the bottom. After 1700 these chairs became very common in New England, with three to five slats, usually curved on the upper edge, or straight across both edges. Pennsylvania slat-backs show some variations in style. There the turning was generally plain and straight, while in New England vase and bulb forms were commonest. The front legs usually ended in a ball and the rear legs in a taper foot. Five and six slats were common, with the lower edges curved up sharply, following the curves of the upper edges. A very common type of modern piazza chair is based directly on the old slat-back form. The first bannister-backs appeared in both England and America about 1700 and were called also split-back chairs. They were very evidently a development of the high-backed walnut chairs of the Restoration, for they showed the Spanish feet, carved top of back, and occasionally the carved underbrace, and the general proportions were the same. But they had rush seats instead of cane or upholstery, and in place of the cane or upholstered panel in the back there were three to five — usually four — upright spindles or balusters between turned stiles. These balusters were turned and split, the flat side being occasionally toward the back but more often toward the front.

In this country the bannister-backs were made of two or three kinds of wood in a single chair and were usually painted. They were made with and without arms. These

were the true bannister-backs, but the name has also been applied to

the later forms. After 1725 they were much simplified in America, the

carved tops and Spanish feet disappearing and giving place to plain

curved or horizontal pieces at the top of the back, and straight,

turned legs and underbraces. After 1735 or thereabouts the turned and

split balusters became less common and in their place appeared plain

or grooved uprights, flat on both sides. This form was common up to

1750 and persisted to some extent till about 1775, being gradually

superseded by the more comfortable Windsors. |