| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IX OTHER AMERICAN SILVERSMITHS THAT silversmithing was one of the most extensively practised industrial arts in this country, not only in the eighteenth but also in the seventeenth century, is evidenced by the amazing number of men engaged in it. Mr. R. T. Haines Halsey has collected the names of about four hundred who plied their trade in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia before 1800, and Mr. George Munson Curtis has recorded the names of over two hundred who worked in the State of Connecticut prior to 1830. Add to these the names of those in Baltimore, Newport, and elsewhere, and the list assumes astonishing proportions, quite at variance with our ideas regarding the poverty of the Colonies and the young nation. The present widespread interest in American silverware is of recent development. In fact, a decade ago the notion was prevalent that most of the old silver in this country was of English origin. The splendid loan exhibition of American silverware held at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1906 was largely instrumental in dispelling this idea. On that occasion three hundred and thirty-two pieces of early American silverware were shown, including the work of some ninety silversmiths of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the American public had its eyes opened to the excellence and beauty of their craftsmanship. Again, in 1909, at the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York, about one hundred and fifty pieces of American silver were on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, including the work of forty silversmiths of New York State. The excellent work of Mr. R. T. Haines Halsey and Mr. John Henry Buck in preparing the catalogues for these exhibitions had much to do with our present knowledge of and interest in this subject.

The process of manufacture, which is described in detail by Mr. Halsey in a footnote in the Boston Museum catalogue, consisted, briefly, in casting the metal in sheets thinner than an ingot, and fashioning the various pieces from these sheets. They were first rolled or hammered to the requisite thickness, cut out with shears, and hammered, in the case of hollow ware, over a mold or form. The finer finishing was done with the hammer. Handles, etc., were cast in pewter, lead, or sand molds and finished by hand tools. Engraving was the principal form of decoration relied on, with some repoussé work. During the last half of the eighteenth century the style of these decorations was for the most part armorial and rococo. The older ware, which was made from rolled and hammered ingots, presents a softer sheen, more pleasing to the connoisseur, than the harder polish of the later ware made from thinner metal sheets. "This silver," to quote Mr. Halsey, "is of the period when the ancient geometrical shapes held sway among craftsmen; when purity of form, sense of proportion, and perfection of line were preferred to elaborateness of design." For sheer grace of form, indeed, it would be difficult to improve upon the best examples of this period. In New York, Dutch and Huguenot elements entered into the development of style, but in New England the ideals of the Scotch and English designers of the time formed the basis of the work, producing a sort of modified and simplified Georgian. But the American silversmiths did not copy — they created. They made no attempt to reproduce the more elaborate styles of English baronial and ecclesiastical plate, but worked along more austerely classic lines, softened by the magic touch of native artistry. Marks on American silver are not an infallible guide to their age or origin, for there was no hall or guild in America such as exerted so complete a control over the craft in England. American silver bears no date letter as English ware does. The American silversmiths did mark their work, however, and pretty generally with their names or initials, so that the questions of where made and by whom can usually be answered satisfactorily. As a rule the earliest marks were fashioned after those used by the English silversmiths of the period, and Consisted of the initials of the makers enclosed in shields or circles, sometimes surmounted by a crown. Some makers also used personal emblems, such as John Cony's rabbit and Andrew Tyler's cat. After about 1725 the initials gave place generally to the full surname, often preceded by the first initial or the given name. Mr. Buck, in his "Old Plate," reproduces the more important of the American marks.

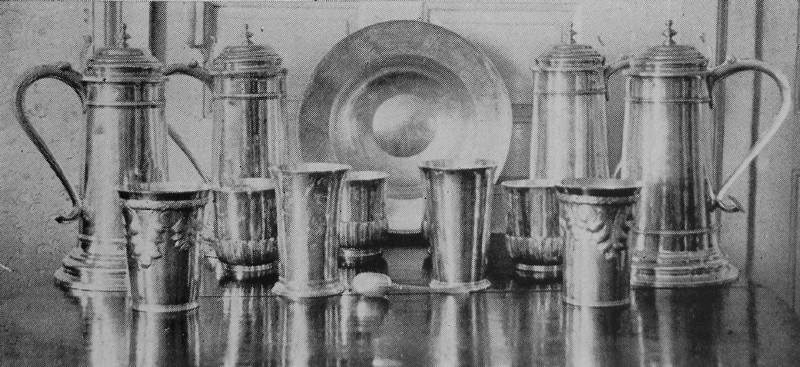

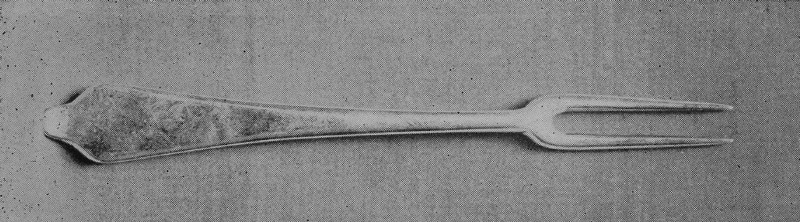

Probably the earliest piece of silverware made in this country was the spoon. The constantly changing shape of this article presents an interesting study in style development which lack of space forbids our going into here — the fig-shaped bowl and hexagonal stem of the seventeenth century followed by the oval bowl, flat stem, trefoil handle, and the rat-tail junction of stem and bowl; then the rounded stem, with the handle turning upward on the front side; the double drop and turned-down handle; after 1760 the pointed ends and heart-shaped bowl, then the round ends, and the fiddle pattern. This development has been traced very minutely by Mr. Luke Vincent Lockwood in Country Life in America for December, 1913. Among the pieces most interesting to collectors are the porringers. This name was originally applied in England to a two-handled cup, often with a cover, similar to what became known in this country as a caudle-cup. In America the name has been universally applied to round, saucer-like vessels with flat, open-work handles or "ears," which were made in considerable quantities up to 1825. It has been variously stated that they were used for eating porridge, for heating liquids over lamps, for wine tasting, and, especially in England, as physicians' cupping and bleeding bowls. This last is a tradition that dies hard, but there is certainly no evidence in this country that the porringer was ever used for any thing but a general utility table dish. Usually only one or two were owned in a family, while actual porridge dishes would be likely to be found in sets. So far as our evidence goes, the porringer was used on the table for sauce, preserves, gravy, etc., and perhaps occasionally for some beverage. At any rate, the porringer is a quaint vessel, no longer in use and hence definitely belonging to an elder day. The variation in the patterns of the handles forms an indication of the period of manufacture, and this development has been studiously traced by Mr. Lockwood. In depth and diameter these porringers varied, too, most of them being five or six inches across, but some larger and some smaller than that. This variation in size and form is, indeed, one of the charms of old silver, and is easily explained. The silversmith did not make up a stock of goods, many from one model, and though he often copied his own patterns there was always a greater or less variation. Then, too, the ware was made usually from the actual coin brought in by the customer, and the amount of this often determined the size of the piece. No two pieces, therefore, are exactly alike, unless ordered at the same time — a condition which never fails to appeal to the collector. Drinking vessels of various sorts, with and with out handles, were very numerous. Drinking, as a social and ceremonial custom, was more common in the eighteenth century than it is to-day, and its equipment was somewhat elaborate. Tippling, in fact, was a prevalent American vice, and there were the proper vessels in both silver and glass for rum, wine, beer, cider, toddy, punch, and flip. In New England, especially, the quantities of cider consumed were astounding, the good fathers apparently living according to the letter of the text, "Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples." There were tankards, six or seven inches high, with S-shaped handles, straight, tapering sides, and hinged covers; cans or mugs, somewhat smaller, usually with curved sides and without covers; flagons, like larger tankards, commonly used with communion services; tumbler-shaped beakers, chalices, and caudle-cups.

Most of the silversmiths made ecclesiastical plate, including communion services, alms basins, and baptismal basins. Many of our older churches still treasure their original pieces. Tea and coffee pots were not common here till about 1730, but they are to be found among the finest examples of the Revolutionary period. The teapots were oval, round, bell-shaped, pear-shaped, conical, or rectangular, with straight or S-shaped spouts, the earlier ones being very small. The first coffee pots were plain, tapering, and cylindrical in form; later examples were curved and more ornate. There were beautiful hot-water urns; braziers, the forerunners of the modern chafing-dish; candlesticks, rarely found to-day; sauce-boats, creamers, salt cellars, lemon strainers for punch, sugar bowls, punch bowls, trays, plates, platters, and other pieces, most of which have been carefully analyzed and classified by Mr. Lockwood. Of the silversmiths themselves a large volume could be written, for they were numerous and their position in early American society was an honorable one. Many of them were wealthy and, like Paul Revere, held positions of importance in the councils of the Colonies and of the young nation. Some lived lives of adventure and romance. In the present discussion, however, we can but mention a few of those who exercised the most telling influence on the development of their craft in this country. Boston, in those days, was our wealthiest and most cultured port, and it was there that the silversmiths thrived in the greatest numbers and produced the largest amount of silverware to be found to-day. Much of it was made from Spanish coin taken in trade with the West Indies. Of the seventeenth-century silversmiths in Boston, the most famous was John Hull. His diary, published by the Massachusetts Historical Society, records the life of a successful merchant prince of old New England. He was born in 1624 in Leicestershire, England, came to Boston in 1635, learned the goldsmith's trade, and became a Freeman in 1649. He acquired wealth in his craft and as a merchant engaged in the West Indian trade. He was also a banker, like other men of his calling. He was active in public life, serving as town treasurer in 1660, as Representative from Wenham in 1668, and as treasurer of the Colony in 1676. He was also a captain in the old Artillery Company. He was a man of learning and a devout church member, being one of the founders of the old First Church of Boston. Antedating Hull was Robert Sanderson, who came over to Hampton in 1638, became a Freeman in 1639, and settled in Watertown, Massachusetts. In 1652 and General Court of Massachusetts, disregarding the higher Court of England, ordered that a mint be set up in Boston and appointed Hull mint-master. He chose Sanderson as his colleague, and also made him a partner in the Silversmith trade. They obtained dies from Joseph Jenks of Lynn, our first iron founder, and continued for thirty years to coin the famous pine-tree shillings. Hull died in 1683 and Sanderson ten years later. Jeremiah Dummer (1645-1718) was the son of one of the early settlers of Massachusetts and was an apprentice of John Hull, having been bound to him from 1659 to 1667. He became a man of importance and substance as well as a skilled silver smith. He served as an officer in the artillery, as selectman, justice of the peace, treasurer of his county, a judge of one of the inferior courts, and one of the Council of Safety of 1689. In 1710 he engraved and printed the first paper currency for Connecticut. He was the father of Lieutenant-Governor Dummer of Massachusetts. His silverware was represented in the Boston exhibition of 1906 by twelve pieces. The next eminently prosperous silversmith in Boston was John Cony (1655-1722). He was a brother-in-law of Dummer and very likely learned his trade from him. He was an engraver as well as a silversmith and is supposed to have made the plates for the first paper money in America. Cony was a prominent member of the Second Church of Boston and in 1689 was one of the original subscribers toward the erection of King's Chapel.

John Edwards (1687-1743) was the son of a Boston surgeon and a man of education and high social position. He was a maker of fine silverware, with a shop at 6 Dock Street, and was one of the wealthy men of his time. The inventory of his estate showed a value of £4,840. His son Thomas (1725-55) carried on his business after him; his brother Samuel and his nephew Joseph were also goldsmiths, and his brother-in-law, John Noyes. The most interesting Boston silversmith of the first half of the eighteenth century, and perhaps the finest craftsman of them all, was Edward Winslow. He was born in 1669, being the grandson of John Winslow, who came over in the Fortune in 1623. On his mother's side he was descended from Anne Hutchinson. He received his goldsmith's permit from the selectmen in 1702. He served as constable, tithing-man, overseer of the poor, colonel of the Boston Regiment, captain of the Artillery Company, sheriff of Boston from 1728 to 1743, and judge of the Court of Common Pleas from 1743 till his death in 1753. Other Boston silversmiths whose work has proved especially fascinating to collectors were David Jesse (died 1708), John Dixwell (1680-1735), James Turner (middle of the century), William Cowell (1682-1736), William Cowell, Jr. (1712-1761), and Andrew Tyler (1691-1741). After Winslow's day the trade gradually became concentrated more or less in the hands of the Hurds, the Burts, and the Reveres. John Burt, who died in 1745, is thought to have been an apprentice of Timothy Dwight (1654 1692). He was a prominent Bostonian and very wealthy for that time, his estate being appraised at £6,460. He produced a considerable amount of fine silverware, being represented at the Boston exhibit by a dozen pieces. He was succeeded by his two sons, Samuel (1724-1754) and Benjamin (1729 1804). To the latter we are indebted for a large proportion of the finer ware of his time. Captain Jacob Hurd (1702-58) was one of the largest producers of his craft, eighteen examples of his work being exhibited in Boston in 1906. He was succeeded by his sons Nathaniel and Benjamin. The former (1729-77) became famous as a copper plate engraver. He made portraits of prominent men, English and American, as well as American scenes and bookplates. The old Harvard College bookplates were made by him. Daniel Henchman (1731-1775), Jacob Hurd's son-in-law, was also a Silversmith.

Although nearly two hundred silversmiths plied their trade in New York prior to 1800, there is comparatively little old silver of New York origin to be found to-day outside of the old churches. While New York in the early days was an important trading center, money was scarce and silverware an un known luxury in most of the homes. Up to the middle of the eighteenth century the New York silverware was chiefly Dutch in style; after that the English influence became predominant. The church communion services, with their engraved beakers and later chalices, and household plates, mugs, tankards, flagons, and teapots comprise the major portion of early New York silverware now extant. The tankards were especially fine. Nor do the names of the early silversmiths of New York suggest as much of romance or historical interest as do those of Boston. They were, nevertheless, men of importance in the community. One of the earliest of the Dutch silversmiths was Ahasuerus Hendricks, who was born in Holland and came to this country at some time prior to 1675. He held the offices of constable and collector and was a prominent member of the Dutch Reformed Church. He lived in Smith Street. A contemporary was Carol Van Brugh, who lived in the Fort. He was the son of an alderman and himself became high constable in 1689. He was the maker of a gold cup presented to Governor Fletcher in 1693. Le Roux was the name of a family of Huguenot silversmiths who worked in New York for over half a century. Bartholomew Le Roux, the earliest of them, took a prominent part in the Leisler Rebellion in 1689, as did also John Windower, another silver smith. Le Roux later became a constable, assessor, collector, and assistant alderman. He died in 1713. Jacob and Hendrick Boelen, father and son and also partners, were Dutch silversmiths who came to New York shortly after 1680 and enjoyed a large share of the trade in that city during the closing years of the century. The father was an assessor, brantmaster, and alderman. Among

the earliest native silversmiths were Jacobus and Johannes Van der

Spiegel. The for mer was an assessor and constable. Others of Dutch

descent were Garret Onclebagh, an alderman who was convicted of

coining money; Cornelius Kierstede, a man of high social connections

who afterward moved to New Haven; Bartholomew Schaats; and the Van

Dycks, who held a large part of the silver trade for half a century,

beginning about 1700.

Peter Van Dyck was a native New Yorker who may have learned his trade from Bartholomew Le Roux. He was a constable and an assessor and withal a craftsman of artistic gifts surpassing those of most of his contemporaries. Charles Le Roux, the son of Bartholomew, carried on his father's business after his death and also figured as an engraver and as sealmaker to the city. He also became an alderman and an attorney. His gold and silver snuff-boxes were famous. Of the eighteenth-century silversmiths in New York there were William Huertin, a Huguenot; George Ridout, who came from London in 1745; John and Peter Targee; Richard Van Dyck, son of Peter, whose store was in Hanover Square; Cary Dunn, who worked from 1765 to 1796 and made popular the pineapple style; Adrian Bancker, Free man Woods, Myer Myers, Jabez Halsey, and a hundred others of greater or less importance. In Philadelphia about one hundred silversmiths had been at work prior to 1800. One of the earliest was Cæsar Griselm, or Ghiselin, who came over with William Penn and who made silver spoons of English design. Among the most prominent silversmiths in Philadelphia were Philip Syng (1676-1739) and his son Philip, who was born in 1703, retired in 1772, and died in 1789. The son was a personal friend of Benjamin Franklin and a member of the American Philosophical Society. He made the famous ink stand, now in Independence Hall, in which the quills were dipped that signed the Declaration of Independence. Others whose work was of superior quality were John Hutton (1684-1792), John David (1763 1797), Elias Boudinst or Boudinot, who worked about 1747 to 1749, Joseph Anthony, Joseph Shoe maker, and Daniel Dupuy. Newport was another town where the craft flourished, for it must be remembered that it was a wealthier place than New York from 1726 until the Revolution. The principal silversmith there was Samuel Vernon (1687-1737), who made quantities of tankards, pitchers, porringers, cups, spoons, pep per shakers, knee and shoe buckles, etc. His mark consisted of the initials S. V. above a clover leaf or cross inside a heart. Other Newport silversmiths, thriving about the middle of the eighteenth century, were Jonathan Otis and Daniel Rogers. After the Revolution, Providence became the center of the trade for Rhode Island, the prominent names being Saunders, Pitman, and Cyril or Seril Dodge. To a later period belongs Jabez Gorham, born in Providence in 1792, and founder of a celebrated house of silversmiths. The most romantic figure among the Rhode Island silversmiths was Samuel Casey, who was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged for counterfeiting. The night before the execution was to take place he was rescued, was placed on horseback, and escaped, never to be heard from again. As Mr. Curtis's investigations have shown, the towns of Connecticut supported a large number of skilled silversmiths. The earliest on record was Job Prince of Milford, who died about 1703 and about whom very little is known. In Norwich René Grignon, a Huguenot, made silverware for a short time between 1708 and 1715. New Haven was the city of first importance in Connecticut for this trade, with Hartford second. The pioneer in New Haven was Cornelius Kierstead (or Kierstede), who came from New York in 1722. Others followed, including Captain Robert Fair child, Abel Buel, and Ebenezer Chittenden in New Haven; John Potwine, Colonel Miles Beach, James Ward, and James Tiley of Hartford; Major Jonathan Otis of Middletown; and Captain Pygan Adams of New London, who was a prominent merchant, church member, and member of Assembly, and one of the best of the Connecticut silversmiths. The trade seems to have thrived more or less in various Massachusetts towns — at Newburyport, Salem, Worcester, Roxbury, Hingham, and Hull. In Newburyport the Moulton family monopolized the trade for one hundred and twenty years, beginning with William Moulton in 1690. Joseph Moulton, who practised his craft during the last half of the eighteenth century, added to his fortune by fitting out privateers to prey upon British commerce. Baltimore, Albany, Troy, Trenton, and other cities had their famous silversmiths, as well as many of the smaller towns. In fact, almost every American town in the eighteenth century had its silver smith, who may also have been the clockmaker, blacksmith, or innkeeper, and who made spoons and silver plate to order, made and repaired jewelry, and did engraving. As the nineteenth century advanced these local craftsmen became fewer until, about the middle of the century, the trade came into the hands of large manufacturers. Collectors have fully appreciated the beauty and historic interest of American silverware for only a few years, but it is now being sought for more earnestly than that of English make. The result has been a rapid increase in values. The record price of $1,650 an ounce, paid at Christie's in London for a piece of Charles II silver, has not been approached in this country, and it is doubtful if such inflated values will ever be reached here. Several hundred dollars for a single tankard, however, is not uncommon, though most of the finer pieces are out of the market and are not purchasable at any price. It would be almost impossible to appraise accurately rare examples of Vernon's, Winslow's, or Peter Van Dyck's work, or the best of Paul Revere's.

As a rough basis for the valuation of ordinary beakers, tankards, porringers, and other hollow ware, the following figures may serve: Pieces made up to 1750, $20 or more an ounce; 1750 to 1800, $5 to $10 an ounce; 1800 to 1840, $1 to $5 an ounce. Plates and other flatware usually bring lower figures, while spoons are comparatively common. Eighteenth-century spoons are worth $8 or $10, and nineteenth-century spoons $2 to $3 apiece. with such values current, there is naturally a temptation to counterfeit old silver; but while a set of rules for determining authenticity could be given, none would prove infallible. The only safe way is to secure the services of an expert in making any considerable purchase. |