| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

Simon Willard. From a portrait owned by the Misses Bird, Dorchester, Mass. CHAPTER VI THE WILLARDS AND THEIR CLOCKS CONNECTICUT and Massachusetts were not as close together a century ago as they are to-day, yet there was undoubtedly some rivalry between the clockmakers of the two States. The Yankee ingenuity of Terry and Thomas in constructing good clocks at cheap prices undoubtedly affected the industry about Boston after 1800, for we find the prices there taking a decided drop. The same rivalry still persists in a mild form between the descendants and adherents of the Willards and those of the Connecticut group. Each claims sole credit for revolutionizing the art of clock- making in this country, and a fair comparative appraisal of their work is not easy to arrive at. Simon Willard was making clocks before Eli Terry was born, and therefore has the advantage of priority. In the matter of design, the clock-cases of both Simon and Aaron Willard surpassed anything made in Connecticut, with the possible exception of Terry's pillar and scroll-top clock. In mechanical genius, however, Terry, Thomas, and Jerome were the equals of Simon Willard, and it was certainly the Connecticut clockmakers who turned a journeyman's trade into a great industry. In the eyes of the collector, beauty must always count largely, and in this the palm must be handed to the Willards. Their mahogany tall clocks and their banjo clocks are a delight to the connoisseur. Simon and Aaron Willard were true craftsmen. The Willards came of good New England stock. Major Simon Willard, an ancestor, was the founder of Concord, Massachusetts, and took a prominent part in King Phillip's War. The clockmakers were the sons of Benjamin and Sarah Willard, who had twelve children. One of the elder sons was Benjamin, born at Grafton, Massachusetts, March 19, 1743. He started as a clockmaker in Grafton, where he probably learned his trade, and began making clocks about 1765. About 1768 he moved to Lexington, and to Roxbury about 1771, where he advertised musical clocks for sale. An advertisement in the Boston Gazette for February 22, 1773, describes clocks playing "a new tune every day of the week and on Sunday a psalm tune. These tunes perform every hour." Little is known of his subsequent career, except that he got into legal difficulties about 1798 and died in Baltimore in 1803. Benjamin Willard's clocks are not as famous or as good as those of his younger brothers, but they are older and rarer. He probably made only tall clocks, some of them in handsome mahogany cases with brass dials. Simon Willard, the eighth son, was by far the most famous, though less successful in a business way than Aaron. He was born in Grafton, April 3, 1753, and his story is set forth in considerable detail in a biography written by his great-grandson, the late John Ware Willard. He spent his boyhood in Grafton, attending school there until he was apprenticed to an English clock maker of moderate abilities, named Morris. He was helped also by his brother Benjamin and soon discovered his own mechanical genius. When he was only thirteen years old he made a tall, striking clock that was pronounced better than any of his master's, doing all the work by hand with file, drill, and hammer. Upon the expiration of his term of apprenticeship he either went to work for his brother for a time or at once started in the business for himself. None of the Willards appear to have been ardent patriots, and their connection with the Revolutionary War was more or less perfunctory. Simon joined Captain Aaron Kimball's company of militia and marched to Roxbury at the time of the Lexington alarm, April 19, 1775. He served for one week. Later he was drafted, but secured a substitute and remained in Grafton during the rest of the war. On November 29, 1776, he married his cousin, Hannah Willard, who died, with her child, in 1777. In 1780 he moved to Roxbury and set up a shop at what is now 2196 Washington Street. Here he lived, with his shop back of the house, until he retired in 1839. As an advertisement he built a big double-dial clock which he hung on the front of the house next door, his own house being too small. This clock was a landmark in Roxbury until 1839, when Willard presented it to the town. On January 23, 1788, he was married again to Mrs. Mary (Bird) Leeds, a widow, of Dorchester, who died July 23, 1823, leaving eleven children. While

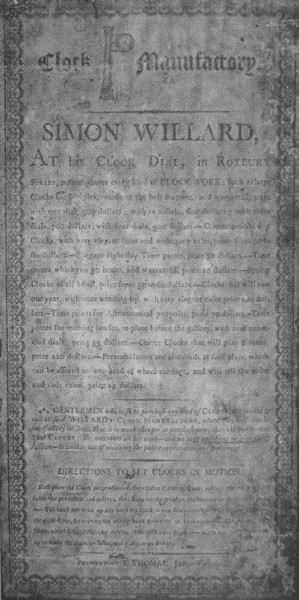

still in Grafton, Simon Willard improved the English clock-jack, a

mechanical device for turning a spit in roasting meat over an open

fire, and in 1784 he was granted the exclusive privilege for five

years (signed by John Hancock) of making and selling his clock-jack

in Massachusetts. In Grafton, he made eight-day tall clocks similar to those of his brother Benjamin, and also a neat shelf clock. In Roxbury, he made, at first, only tall clocks, but later he became equally well known for tower and gallery clocks, and for wall clocks which he always spoke of as timepieces. These clocks he made chiefly during the winter and peddled them in summer along the North Shore, going, at least once, as far as Bangor, Maine. An advertisement of this period gives the following prices: Steeple clocks, one dial, $500; two dials, $600; three dials, $700; four dials, $900; "common eight-day clocks with very elegant faces and mahogany cases," $50 to $60; eight-day timepieces, $30; thirty-hour timepieces, $10; spring clocks, $50 to $60; one-year clocks, fine cases, $100; astronomical clocks, $70; gallery clocks, $55; chime clocks, six tunes, $120. He also made a sort of cyclometer for carriages at $15. In 1801 he invented the improved timepiece which has come to be popularly known, because of its shape, as the banjo clock. It was an eight-day, non-striking, pendulum clock, smaller and more compact than the tall clock, and easily fastened to the wall. It won instant success. In 1802 he got it patented, his papers bearing the distinguished signatures of Thomas Jefferson, President, James Madison, Secretary of State, and Levi Lincoln, Attorney General. A few of these banjo clocks may have been made by him experimentally prior to 1801. In 1819 Willard took out another patent for an alarm clock, but apparently he went to no great trouble to enforce his patent rights, for the banjo clock was early copied by a number of his contemporaries, though none of their clocks equaled his. After 1802, Simon Willard largely abandoned the manufacture of tall clocks and devoted himself to the timepieces, making tall clocks to order only. He began to secure special commissions, too, for tower and gallery clocks which took him away from home, so that he gave up his peddling about 1805. In 1801 he made a large clock for the United States Senate. The principle employed in the works was a new one, so that he had to go to Washington to show the authorities how to run it. Willard's bill for this clock was $770. It was destroyed when the British burned Washington in 1814. While at the Capital, Willard met President Jefferson, and a genuine friendship sprang up between the two men. In 1826, Jefferson gave Willard the commission for a turret clock for the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. The specifications, drawn up by Jefferson himself, were the most complete and accurate that Willard had ever received. They called for a sixty-inch dial. Willard went to Charlottesville to install this clock, which did service for over sixty years. While in Virginia he visited Jefferson at Montecello and also Madison at Montpelier. Simon Willard was a self-educated man and was very proud of his connection with Harvard College and his friendship with its president and faculty. For years he kept the Harvard clocks in order. He presented two clocks to the college, both of which are still in existence. One, a tall clock, stands in the Faculty Room; the other, a banjo-shaped regulator, is in University Hall. Willard was also a friend of Josiah Quincy and made an elaborate timepiece for him as a wedding gift for his daughter in 1826. In 1837 he made two more clocks for the Government. They were set up and tested in his son Simon's shop in Boston and he took them to Washington himself. One was ordered by Associate Justice Story and was placed in the old Senate Chamber, now the Supreme Court. The other was constructed especially for a case designed by Carlo Franzoni in 1819, representing Clio, goddess of history. It is now to be seen in Statuary Hall. On this visit Willard met President Van Buren and other celebrities. During

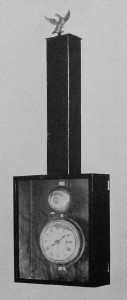

these years Willard installed a number of tower clocks which have

become more or less famous. In 1804 he made a handsome gallery clock

for the First Congregational Church of Roxbury, and in 1806 a

one-dial clock for the steeple of the new meeting-house. His price

was $858. In 1857 four new dials were placed on the steeple;

otherwise the clock is the same. Willard had charge of the running of

these clocks as long as he remained in Roxbury. Willard's great-grandson compiled the following fairly complete list of his public clocks: First Church of Dedham, 1820 (replaced). Old State House, Boston (now running). U. S. Senate, 1801 (destroyed 1814). Jefferson College, afterward the University of Virginia, 1826 (destroyed by fire 1895). First Church, Roxbury, 1806. Park Street Church, Boston (replaced 1906). North Church, Newburyport, 1785 (destroyed by fire 1861). Boylston Market, Boston (still running). North Church, Portland, Maine, 1802 (replaced 1893). Chief Clerk's Office, U. S. Supreme Court, 1837 (still running). The Franzoni Clock, 1837 (still running). First Unitarian Church, Cambridge, 1832 (still running). First Congregational Church, Falmouth. Willard returned to Roxbury for good in 1837 and retired from business in 1839. For three years he lived with his son, Simon, Jr., in Boston, and for two years with his son-in-law, Edward Bird of Dorchester. In Boston he spent a good deal of his time in his son's shop, loath to leave the vocation he loved. In Dorchester he continued to amuse himself in the shop of Elnathan Taber, an old friend and apprentice of his. After 1845 he lived with his daughters, Mrs. Hobart of Milton and Mrs. Isaac Cary of Boston. He retained his keen faculties to the last and died quietly at the Cary home in Washington Street on August 30, 1848, in his ninety-sixth year. Simon Willard was a great inventor and crafts man, but a poor business man. His fortune was but $500 when he retired and he died poor. He was honest, proud, and sensitive. He was a tireless worker, often spending twelve or fourteen hours a day at his bench. During his lifetime it is estimated that he made about 1,200 eight-day clocks and 4,000 timepieces, besides the others. He also invented and manufactured machinery for turning lighthouse turrets. In some respects his clocks have never been improved upon. It is, of course, the shelf clocks, tall clocks, and timepieces in which the collector is chiefly interested. The first clocks he made in Grafton were thirty-hour shelf clocks, about twenty-six inches high in plain cases of cherry or mahogany with brass dials. The movement was good, forming the basis of his later timepiece. These shelf clocks are valuable to-day because of their rarity. He also made a few miniature tall clocks, about two feet high, with fine mahogany cases and brass dials. These are very rare. Simon Willard's tall clocks were made chiefly between 1780 and 1802. They were eight-day striking clocks with excellent works of hammered brass, cut out by hand with a file. He is said to have become so expert that he could cut the teeth of the wheels with absolute accuracy by his eye, with no marks to guide him. The steel pinions were also made by hand. At one period Paul Revere is said to have made some of Willard's brass castings. Working alone, Willard could turn out one of these tall clocks in six days. Later, with better tools, he averaged one timepiece a day without case. During his latter years he made some use of an English wheel-cutting machine. The movements of these clocks, some of which have kept excellent time to this day, are wonderful examples of file work; and more remarkable still, the craftsman's hand lost none of its cunning as the years advanced. At the age of eighty-five he was as skilful as when he first opened his shop in Roxbury. The original rods of the long forty-inch pendulums were of selected wood, baked hard and polished. In most of the clocks now extant these pendulums have been replaced by later ones. The original weights were of brass filled with shot. The dials, generally of iron, sometimes of wood, were painted with eight or ten coats, each rubbed down till the finish was like enamel. A few of the earlier clocks had Arabic numerals, but they were usually Roman. Some of the dials were finely decorated by artists, one of whom was a Charles Bullard. Simon Willard did not make his own cases or dials, but he demanded always the best of workman ship. The cases of his tall clocks were made by Henry Willard of Roxbury, Charles Crehore of Dorchester, William Fiske of Watertown, and others. They were made on the same general model, from carefully selected, well seasoned oak, mahogany, and cherry, occasionally inlaid with satin wood or holly. On the top of the hood were placed brass urns, balls, or spikes, rarely the eagle. Some of these tall clocks had chime or musical attachments and the dials often told the days of the month and the phases of the moon. The patent timepiece or banjo clock of 1802 be came at once popular because of its convenience, its graceful shape and decorative finish, and its excellent timekeeping qualities. The movement which, as well as the form of the case, was original with Willard, was designed for economy of space and ran with a shortened pendulum. There

were three types of banjo clock. The first had a plain mahogany case,

occasionally inlaid, with curved brass side ornaments, but with no

glass front and no bracket. The second kind, which was made in the

largest quantities, had a mahogany case, brass side ornaments, and

glass front, but no bracket or base piece. The most ornate kind was

known as the presentation clock and was of mahogany and white enamel

with gilded beading and painted glass front, and with an ornamental

base bracket. The presentation clocks were popular as wedding gifts

and cost $80 or more. Josiah Quincy's purchase was one of these. The top ornaments varied, brass balls, urns, and brass or gilded wooden acorns being commonest. Simon Willard seldom if ever used the spread eagle, which was often added later and was much used by his imitators. The dial glasses were slightly convex. The glass fronts were painted chiefly by Charles Bullard and an Englishman whose name has been lost. The de signs were chiefly lacy arabesques and scroll work, leaf designs, etc., executed in gold leaf on a white ground. The door glasses were usually painted with borders of gold and black on a white ground, or various color combinations, with an oval or oblong space left in the center through which the swinging pendulum might be seen. Simon Willard did not use landscapes, pictures of battles, ships, flags, or eagles on these door glasses, and no gilt on the wooden cases except on the gift clocks. He made a few mahogany timepieces of a slightly different design as regulators for banks and offices. His gallery clocks usually had gilt cases with large round dials surmounted with the spread eagle. The short pendulum cases had painted glass fronts and usually rested on a bracket. None of the Willards made clocks with wooden works. Simon Willard signed many of his tall clocks on the dials and his timepieces — generally "S. Willard's Patent" — on the doors of the pendulum cases. Though several of the Willards were in the clock business, they were none of them partners. Next to Simon in fame was his younger brother Aaron, who was born October 13, 1757, and may have learned his trade from Benjamin or Simon in Grafton. In 1775, Aaron marched to Roxbury with the Grafton Militia, as a fifer, and served for a few weeks. In 1780, he moved to Roxbury and opened a shop near Simon's. He was a better business man than his brothers and he prospered from the start. He peddled his clocks along the South Shore, while Simon covered the North Shore. Aaron Willard moved to Washington Street, Boston, about 1790, and established a factory connected with his house. A little colony of his employees and the allied trades — cabinet-makers, painters, etc. — soon grew up about him and other clockmakers were attracted to the neighborhood, so that by 1816 it had become the clockmaking quarter of the city. Here he prospered, employing twenty or thirty workmen, and retired, well-to-do, about 1823. His business was continued by his son, Aaron Willard, Jr., who originated the lyre clock and produced many styles to meet the changing demands. Aaron, Sr., died in 1844., at the age of eighty-seven. Aaron Willard first made tall and shelf clocks, and later banjo clocks, gallery clocks, and regulators. The styles of his tall clocks varied considerably in excellence. The cases were usually of mahogany, sometimes of oak or Cherry, and occasionally inlaid. He produced several styles of shelf clocks, standing about thirty inches high, of no very great distinction in design. About 1802 Aaron copied his brother's patent timepiece, changing the pattern somewhat. His glass fronts were never so finely decorated as were Simon's and he generally painted a picture on the doors of his pendulum cases. He used gold beading and base brackets more often than Simon. In general, Aaron Willard's clocks, while not lacking in decorative merit, were somewhat inferior to Simon's. But he made more of them and they are to be found somewhat more frequently to-day. Ephraim Willard, another of the brothers, born March 18, 1755, followed the trade of watchmaker and clockmaker in Medford and Roxbury. In 1801 he moved to Boston. He made a few tall clocks which are now very rare. Two or three of Simon Willard's sons followed their father's calling. Simon, Jr., the second son, born in 1795, left school at the age of fourteen to learn the trade. A few years later he gave it up and entered West Point, remaining in the army till 1816. He started a clock business in Roxbury, but failed, and went to New York in 1826 to learn watchmaking. He returned in 1828 and started in business again in Boston at 9 Congress Street, where he be came successful and wealthy. He invented and constructed a wonderfully accurate chronometer or astronomical clock, which for years was the standard. He remained in business for forty-two years and died in 1874. Benjamin

F. Willard, Simon's fifth son, was also a skilled mechanic and

inventor. He learned the clockmaking trade from his father. Like all

of the Willards, he started as a poor lad and passed through a severe

struggle before success came to him. He was born in 1803 and died in

1847.

Simon Willard had many apprentices, much of whose work is worth knowing. of these the best known was Elnathan Taber. When Willard re tired, Taber bought his tools and continued the manufacture of the patent timepieces, most of which were sold by Simon, Jr., in his Boston store at $16 apiece. Some of these clocks are marked "Simon Willard, Boston," but should not be confused with the original timepieces marked "S. Willard's Patent." Other makers also made use of the Willard name in some form or other, but their banjo clocks lack the decorative grace of the originals, and the imitators more frequently used the spread eagle on top and pictures of naval battles of the War of 1812, landscapes, etc., on the pendulum cases. Sometimes they introduced striking attachments. Other apprentices who were afterward successful were Levi and Abel Hutchins, William Cummins, and William King Lemst. Among the other contemporaries who followed Willard's styles more or less may be mentioned Samuel Mulliken, David Wood, and Thomas Balch of Newburyport, Benjamin Bagnall, Jr., of Boston, Daniel and Nathaniel Munroe and Samuel Whiting of Concord, Massachusetts. Most noteworthy of all was Lemuel Curtis, who made banjo clocks that were even more elegant than Simon Willard's presentation clocks. Curtis was born in Boston in 1790, moved to Concord in 1814, and took out a patent in 1816 on an improvement on the Willard timepiece. He moved to Burlington, Vermont, about 1818, and died there in 1857. His clocks show much gilding and ornament, and a round instead of a square pendulum case covered with convex glass on which a landscape or some classical or allegorical subject was painted. These

Willards are not to be confused with Philander J. and Alexander T.

Willard, who made clocks at Ashby, Massachusetts, between 1800 and

1840. They were probably not related to the Grafton family.

As

in the case of other antiques, present-day values depend largely upon

the eagerness of the purchaser. Willard tall clocks are now so rare

as to be practically out of the market. In New York, where the

highest prices prevail, they are valued at $250 to $500, according to

their condition. Simon Willard timepieces of the ordinary type, with

mahogany cases and no base bracket, are priced at $75 to $85, which

is rather more than they are worth, and good examples of the

presentation clock, with bracket, at $100 or more. An Aaron Willard

timepiece, with the picture of the battle between the frigates Guerrière

and Constitution,

was recently shown in a New York shop window with a $50 price mark.

Doubt less it could be bought for $35 or $40. The Aaron Willard shelf

clocks are worth somewhat less, and good banjo clocks by other makers

may be valued at from $20 to $35, according to style and condition. |

||||||||||||||||||||||