| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IV AMERICAN WINDSOR CHAIRS THE Windsor chair, that graceful, honest product of eighteenth-century America, has at last come into its own. Time was when it was consigned to the porch or the kitchen, or even the garret, simply because it was not mahogany. And when at length the craze for everything old caused the Windsors to be brought out into the light of day, many a misguided owner sought to impart to them a false elegance by having them "done over" and given a "mahogany finish." But

the mahogany fetish is losing a little of its power over us and we

are coming to appreciate other woods and painted furniture, provided

it displays true grace of line, beauty of proportion, and the charm

of quaintness.

The Windsor chair is nothing if not graceful; it is hard to find an ugly example. It is generally comfortable to sit in, which cannot be said of most of its contemporaries. Its construction insures a most unusual combination of lightness and strength. Already the humble Windsor is frequently to be seen cheek-by-jowl with aristocratic Chippendales and Hepplewhites, and the variety of types offers a fascinating field for the collector. Furthermore, the Windsor chair, as we know it best, was a distinctly American product, and therefore makes a direct appeal to the growing interest in Americana. For a full century the Windsor enjoyed wide spread popularity in both England and America as the common, inexpensive, every-day chair of tavern, cottage, and farmhouse. The origin of both name and style is obscure. The oft-repeated legend has it that George II of England, while hunting near his castle at Windsor, was caught in a storm and sought shelter in a shepherd's hut. Here he found a chair, the like of which he had never seen before, which had been laboriously fashioned by the shepherd with his pocket knife. The King, greatly pleased with its grace and comfort, had it copied, and so the vogue of the Windsor began. Like the story of Dr. Gibbon's mahogany candle- box and most others of this sort, the legend should not be taken too seriously. George II's reign began in 1727, and Windsors appeared in this country very soon after that and were possibly made to some extent in England before 1725. It is quite probable, however, that the form was first conceived in some rural neighborhood, for everything about it suggests a humble origin. The Windsor chair, as we know it, was most likely the result of a gradual evolution, having its beginning somewhere in England during the first quarter of the eighteenth century, and reaching its highest development in this country. For though the Windsor chair certainly achieved some popularity in England, it was in America that it enjoyed its widest vogue and under went the greatest variation of form. English writers on old furniture pay scant attention to the Windsor, while no consideration of Americana would be complete without it. The statement is commonly made that the vogue of the Windsor in America extended from 1725 to 1825. It is possible that there may have been some English Windsors here as early as 1725, but I have been unable to discover any authentic evidence to prove it. Dr. Irving Whitall Lyon, author of "The Colonial Furniture of New England," published in 1891, and the pioneer investigator in this field, made a careful study of this subject. The earliest reference he found to Windsor chairs was in the will of Governor Patrick Gordon of Pennsylvania, who died in 1736 and in whose inventory five Windsor chairs were mentioned. Governor Gordon came from England to Philadelphia in 1726, bringing his household goods with him, and it is quite possible that the Windsors may have been among them. Windsors are also mentioned in the will of Hannah Hodge, widow, of Philadelphia, who died July 7, 1736. After that date references to Windsor chairs be came more and more frequent, and by 1745 they had apparently become popular in Philadelphia and their local manufacture may have begun as early as that. By 1760 the vogue for Windsors was in full swing. The earliest mention of Windsors in New York was found in the inventory of Abraham Lodge, attorney, who died June 8, 1758. Soon afterward Philadelphia-made Windsors were advertised in New York newspapers. They rapidly became fashionable in New York, supplanting the old rush-bottomed slat-back and bannister-back chairs in popularity, and in a few years more were being manufactured there. Windsor chairs were not made in Boston till about 1786, but were sent there from Philadelphia or New York. In 1769 two Windsors were appraised at six shillings each in the inventory of Captain Daniel Malcolm of Boston, and in 1773 two at ten shillings in the inventory of Samuel Parker. The Independent Chronicle of Boston for December 29, 1785, contained an advertisement of Philadelphia Windsors on sale at "Messrs. Skillin's carver's shop near Gov. Hancock's wharf." In the same paper on April 13, 1786, appeared woodcuts of two Windsor chairs in an advertisement of Ebenezer Stone's shop — "Green Windsor chairs of all kinds equal to any imported from Philadelphia. Chairs taken in and painted." There was no single maker of Windsor chairs whose name stands out preëminent like that of Duncan Phyfe, and though Philadelphia was first in the field and remained the center of the industry, the manufacture of Windsors was confined to no single locality. Like clock cases, they were made by almost every village cabinet-maker. In the cities they were advertised by nearly all chairmakers, but there were a number of specialists who made nothing but Windsors. In

1773 Jedediah Snowden advertised domestic Windsors in the

Philadelphia Journal.

In the Philadelphia Directory of 1785 the names of eleven Windsor

chairmakers appear, besides half a dozen other chairmakers and a

number of cabinet makers.

The manufacture of Windsor chairs in Philadelphia, however, must have begun at least as early as 1760, for in 1763 Perry Hayes & Sherbroke in New York advertised "Philadelphia-made Windsor chairs." In 1768 a joiner in Prince Street, New York, advertised "Windsor chairs made and sold by William Gautier. High-backed, Low-backed, Sack-backed, and settees, also dining and low chairs." In the New York Gazetteer of February 17, 1774, Thomas Ash, of Broadway, advertised an extensive line of Windsors. The first New York City Directory, published in 1786, gives the names of Thomas Ash and Lecock & Intle as Windsor chairmakers, besides several other chairmakers. In the New York Directory of 1789 appear the names of nine Windsor chairmakers and ten other chairmakers. By this time there were several makers of Windsor chairs in Boston, while the Baltimore Directory of 1796 gives the names of six Windsor chairmakers besides the other manufacturers of furniture. In Salem, Massachusetts, Samuel Phippen was making Windsors in the '80's. In 1786 Stacy Stackbone, according to an advertisement in the Connecticut Courant for January 30 of that year, moved from New York and engaged in the manufacture of Windsor chairs in Hartford, near the State House. The New Haven Gazette for February 22, 1787, shows a woodcut of Windsor chairs and the advertisement of Alpheus Hews from New Jersey, maker of Windsor chairs and settees, garden chairs, and children's chairs, on Chapel Street. According to the Connecticut Gazette of November 14, 1788, William Harris, Jr., was making Windsors in New London. The United States Chronicle of Providence, R. I., printed on July 19, 1787, the advertisement of Daniel Lawrence — "Windsor chairs. Neat, elegant, and strong, beautifully painted after the Philadelphia mode, warranted of good seasoned materials so firmly put together as not to deceive the Purchaser by an untimely coming to Pieces." The

foregoing references indicate the extent to which the industry had

grown a few years after the Revolutionary War. The major portion of

the Windsors found to-day are of that period. The fashion declined

soon after 1800, though Windsors were made and sold in considerable

quantities for twenty years thereafter, special advertisements

appearing in New York papers as late as 1818.

Windsor chairs were never made of the more elegant cabinet woods, and it is a mistake to have them so treated in renovation. They were usually made of two or three kinds of wood in the same piece — the hoop of the back of hickory; spindles and arms ash or hickory; legs oak, hickory, or maple; seats pine, whitewood, beech, etc. Windsors were almost invariably painted. Green seems to have been the popular color at first — usually dark green or apple green — but black chairs are to be found to-day more often than green. Some were undoubtedly painted to suit the purchaser — usually red or yellow. of course it is not uncommon to find several coats of paint on old specimens, black frequently hiding the original red or green. I have never known of a Windsor that was originally painted white and doubt if they were ever finished natural in this country. Occasionally a simple decoration is to be found, such as a line of yellow on the black, but that was usually a later addition. Though American Windsor chairs vary widely in form, from the loop-back side chair to the comb- back rocker, their type characteristics are unmistakable. The most noticeable of these are the slender, round, upright spokes or spindles in the backs, varying in number but in general presenting the effect of a graceful outline filled with parallel lines. The chair backs are slanted backward, are straight from top to seat, and curved laterally to fit the back. The arms of the armchairs also slant outward. The spindles are tapering or slightly bulging on the best examples; straight, cylindrical, and less slender on the poorer ones. The outer spindles of the arms and of the backs of the fan-back chairs were turned more or less elaborately on a lathe; the hickory spindles were usually not turned, but cut out with a spokeshave and rounded with a file, so that they present a pleasing lack of absolute uniformity, The seats were made of a single piece of plank, varying somewhat in outline, and hollowed out more or less in the fashion known as saddle-seat. All

this shaping, curving, and outward slanting made for both grace and

comfort. The placing of the legs was a matter of strength as well as

design. They were set into the seats at some little distance in from

the corners and were sharply raked or slanted outwards, the feet in

the best examples extending beyond the line of the seat. The legs

were lathe turned, usually in vase forms. The tendency in some of the

later work to reduce all the turning to a conventionalized bamboo

pattern indicates a lazy habit in the maker.

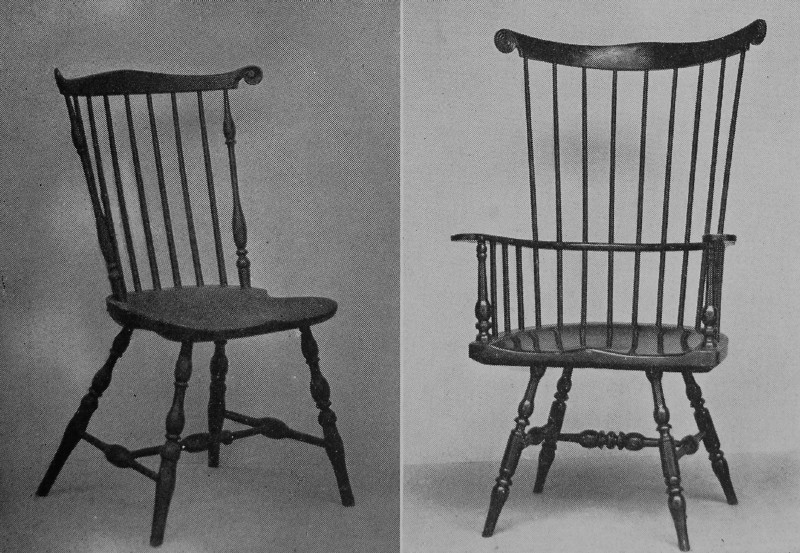

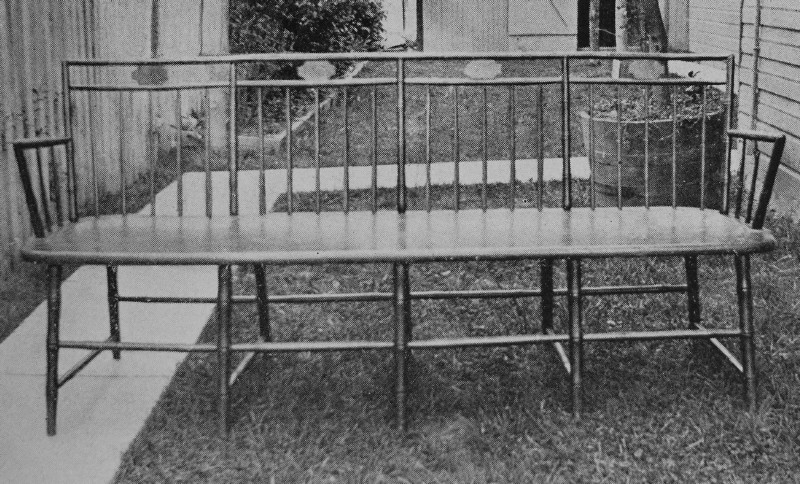

The underbracing consists almost invariably of three bulb-turned pieces, two connecting the front with the back legs, and the third joining these two at the middle. In general, though light and airy in appearance, the Windsor chair is exceedingly strong and well braced. The spindles were driven into holes in the seat and fitted into holes in the hoop or the arms at the top. The legs were driven clear through the seats, secured by means of fox wedges, and shaved off flush, the underbraces having first been fitted. The result is a rigidity of construction that has, in a multitude of cases, defied dampness, steam heat, and the weight of a century. Windsor chairs were obviously hand-made, a fact which marks them, in the eyes of those who appreciate form and the evidences of true craftsmanship, as far superior to later imitations and modern machine-made spindle-back chairs of all sorts. A careful analysis of Windsor forms has never, to my knowledge, appeared in print. In fact, the only man I know of who has made an analytical study of the subject is Mr. J. B. Kerfoot, who has accumulated a large and interesting collection of Windsors at his home in Freehold, New Jersey. I am indebted to him for the suggestions leading to the following classification, which, though brief and incomplete, may serve to clarify our somewhat jumbled notions regarding Windsors and may perhaps lead some enthusiast further into a fascinating field of investigation. American Windsors may be divided roughly into three groups — New Jersey, New England, and Pennsylvania German. The New Jersey group includes the work of the prolific Philadelphia makers which found its chief market in New Jersey rather than in Pennsylvania. The chairs made in Trenton follow the Philadelphia lines, as, in fact, do a good many of those made in New York. The New England types, which found their Way often into New York State, display, in the main, certain common characteristics, in spite of the differences to be found between the work of the makers of Connecticut and of eastern Massachusetts. The chairs found on Long Island belong more often to the Connecticut than to the New Jersey group. American Windsors may again be arranged in seven general classes: (1) the New England or loop-back side hair; (2) the New England or loop- back armchair; (3) the hoop-back armchair; (4) the fan-back; (5) the comb-back; (6) the low-back; (7) the miscellaneous variations. There has been a considerable confusion of terms in all writing on this subject; I propose to employ those which seem most definitely descriptive. The term loop-back, I must confess, is my own invention. The first type is the simple side chair, with shaped seat and with the outline of the back in the form of a loop. It is the commonest type to be found in New England and on Long Island to-day, but is infrequently seen in New Jersey or Pennsylvania. The second is simply the armchair of this species, with the loop carried forward to form the arms. This, also, was a New England product and is one of the most graceful of all the Windsors, though not as strong as the extension or hoop-back form. It is also known, in some localities, as the fiddle-string armchair. In a later form the loop is carried to the seat as in the side chair and the arms are set on at right angles. The hoop-back is the commonest and most useful of the armchairs. The back is cut in two horizon tally by a semi-circular piece which, extending for ward, forms the arms. From this a hoop-shaped piece, usually round, extends upward, forming the top of the back. The spindles pass through holes in the middle piece, joining the hoop to the seat. This form apparently originated in Philadelphia and belongs to the New Jersey group, being introduced into New England later. It was perhaps the kind which Gautier advertised as sack-backed. In the majority of cases the ends of the arms are flat and merely rounded off, but the most valuable examples have the ends carved in a scroll resembling a closed hand. It is doubtful if this carved form was ever made in New England, though probably imported there from Philadelphia. There is, in fact, a considerable variation in this one type, particularly in the height of the hoop. At some time after the middle of the nineteenth century the hoop-back Windsor was revived in Philadelphia and large numbers were made and sold, especially as office chairs. But the form was heavier and is easily distinguished. Most of the modern reproductions are also of this type. The

fan-backs have a horizontal curved or bow-shaped piece at the top,

from which the spindles slant slightly inward toward the seat, the

outer ones being heavier and turned. The top piece extends slightly

beyond these and ends in curved ears which, generally speaking, were

made plain in New England and were carved in the form of a scroll in

Philadelphia and New Jersey. Arms are occasionally found on fan-back

chairs, with a dividing piece as in the hoop-backs.

The comb-back Windsor is simply one of the other forms with a head-rest added in the form of a miniature fan-back, or like an old-fashioned back comb. This type seems to have been confined to no single section. The least graceful form of the Windsor, but one of the oldest, is the low-back. In this a single, heavy, semi-circular piece forms the arms and the top of the back on the same level, much as in the round about chair. Sometimes the back is raised an inch or two by the addition of another piece. The seat is broad and the whole effect squatty. A variation of the low-back has the addition of a fan-back, rarely a hoop-back, extension above, which scarcely adds to its beauty. There is some reason for believing that the commoner hoop-back armchair was a development of this variation. All other forms are merely local departures from these. Sometimes on both fan-back and loop-back chairs, a portion of the seat is extended back a few inches, from which two divergent spindles extend to the top of the back, as braces, adding at once to the strength and the attractiveness of the chair. Occasionally a broad rest is added to the right-hand arm of one of the armchairs, forming a writing-chair. Sometimes there is a drawer in this rest, and one under the seat, and often an additional rest for a candle. The Pennsylvania group includes most of the Philadelphia or New Jersey forms and some others, rendered somewhat heavier and occasionally more ornate to suit the tastes of the Pennsylvania Germans of that day. The ears of the fan-backs, for example, are sometimes quite fanciful, while some fan-backs found near Manheim show no ears at all, but merely a sharp angle. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century the styles underwent radical changes, various rectangular forms being developed in spindle-back chairs and settees. The history of the rocking-chair is yet to be writ ten. According to some writers rockers began to appear in this country before 1750, and Windsor rockers soon after the Revolution. Others assert that Windsor rocking-chairs were not made until about 1810 and that most of the so-called Windsor rocking-chairs are simply old armchairs cut down and fitted with rockers. Certainly none of the early advertisements or inventories included any mention of rocking-chairs. The first rockers were merely short boards cut straight across the top and rounded on the bottom. Then the top side was shaped, and later the rocker was fashioned much as that of to-day, except that it extended only four or five inches hack of the rear legs. It was not until 1820 or so that the discovery was made that rockers lengthened behind increased the safety and comfort of the chair. During the decade following that astonishing discovery the popularity of the rocking-chair spread rapidly. Windsor rockers were made which soon developed into a variety of special rocking-chair forms, including the famous Boston rocker. The styles of the middle period of Windsor chair-making extended well into the nineteenth century, and with so little change that it is not often possible to judge of the exact age of a chair by its style. The cruder workmanship of a rural chairmaker often lends a false suggestion of greater age. But a study of the styles is interesting for its own sake, and there are fascinating by-paths of research open to the investigator that I have not even touched upon, such as the various patterns in turning, the grooves at the back of the seats, etc., all of them indications of individuality and offering possible clues to the identity of the makers. If space permitted, an interesting chapter could be written about the history of famous Windsors of the writing-chair with revolving seat, now owned by the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, in which Thomas Jefferson is said to have signed or written the Declaration of Independence; of Washington's writing-Chair and fan-back armchair and the thirty Windsors that stood on the veranda at Mount Vernon; of Rev. Ezra Ripley's comb-back writing-chair, afterwards used by Ralph Waldo Emerson and by Nathaniel Hawthorne, and now owned by the Concord Antiquarian Society, together with a number of other historic Windsors. Just

a word in passing regarding the English Windsors. Those most commonly

seen have the familiar rounded back and spindles, but with a pierced

splat in the center of the back. While not all English Windsors had

this splat, it is one of the distinguishing marks, for it was never,

so far as I have discovered, used by American makers. But we do not

need to depend upon that. The whole effect of the English chair is

heavier and less graceful. The back is less pleasantly loop-shaped;

the legs are more nearly perpendicular and are set nearer to the

corners of the seats; the underbraces are placed higher than on

American-made Windsors. Nevertheless, English Windsors are enjoying

somewhat of a vogue among American collectors and are being brought

over in considerable quantities. Some of them are undoubtedly very

fine in design and superior in finish to the American chairs, but

generally they exhibit less evidence of imagination and feeling for

form.

The English chairs include the prototypes of our loop-back side chairs, hoop-back armchairs, and low- back Windsors, with and without the fan-back extension. The American makers developed more variations than did the English, and, in the main, improved upon their designs. These English Windsors can be picked up in Great Britain at £1 to £5 each, sometimes in sets of six or more; in this country they are worth $25 to $50 apiece. Not long ago a New York dealer asked $100 for an English Windsor with the three royal plumes in the splat, and got his price. In spite of the recent awakening of interest in American Windsors, so many of them have been discovered and placed on the market that the values have dropped rather than increased, except on the rarer forms. The low-backed Windsors have been bringing higher prices than they deserve. At a recent sale at the American Art Association galleries, New York, $57.50 was paid for a low-back, while a neighbor of mine picked up almost the duplicate of it on Long Island for $1.50. Statements

made to me by various collectors and dealers have led me to the

following conclusions as to present values: New England loop-back

side chairs are considered worth from $8 to $10 apiece, according to

style. My own pair I got at an auction in Hempstead, Long Island, for

$1.35, and I am inclined to think the above figures too high.

Fan-back side chairs are worth $10 to $12, according to some

collectors; armchairs of various sorts, $10 to $15; the rarer or more

graceful forms would doubtless bring $20 or $25, and comb-backs $35

or $40. The later variations of the Windsor are worth $5 or $10

apiece, and settees $15 to $25. Dealers in cities like New York ask

—

and obtain — rather higher prices than these. A rather more detailed schedule of values has been furnished me by a Windsor collector of long experience and conservative tendencies. Much depends, he says, on style and finish, on the location of the piece in relation to ready markets, etc. The following he considers fair dealers' selling prices for good specimens of the principal types of Windsors:

The

Windsor chair is one of the few things still to be picked up about

the countryside by the sharp-eyed collector, and he can afford to be

a bit discriminating. Let him look for deep and well designed

turning, for widely raked legs, for side chairs with the seats well

shaped and cut in deeply at the sides, for just the right slant to

back and arms, and for grace of line and proportion. These are the

things that count in the Windsor chair.

|