| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER II SAMUEL McINTIRE, MASTER CARPENTER AMONG the most precious of our American heritages of Colonial and post-Revolutionary times are the homes of our forefathers that have been preserved to us. They are precious not only because of their historical associations but because in them still lives a spirit of honest and inspired craftsmanship as true if not as lofty as that which entered into the building of the Cologne Cathedral or the Taj Mahal. We are constantly harking back to them in our attempts to develop an American style of domestic architecture, because there is something about them that has stood the test of time — something good and true and beautiful. What

manner of men designed and builded these fine old mansions and

farmsteads? of Bulfinch we know, of La Trobe and Jefferson and a few

others who were professional or amateur architects. But they were not

the men who conceived the harmonious proportions and exquisite

details of the homes of our forefathers. The domestic architects of

that day were for the most part architects merely as part of the

day's work; they were the builders and master carpenters, honest

craftsmen all, and of them we know all too little. The old Assembly House, Salem, Mass., built in 1782, is fairly typical of the style of architecture employed by Samuel McIntire

The master carpenters of a hundred-odd years ago combined the present professions of architect, contractor, builder, decorator, and artisan. They were workmen who lived with their tools and not in sumptuous city offices. Yet they honored their craft and exalted it. In Boston the guild which met in Carpenter's Hall was composed of men of intellect who were masters of their calling. Alas, their tribe has well nigh perished. The achievements of these men, especially as shown in the private houses of New England and the South, constitute our chief claim to a national and indigenous school of architecture. "For although these houses," as one writer puts it, "were modeled on the style prevalent at the time all over England, they show the common classical and stereotyped forms used with a justness of proportion, a nicety of detail, and a refinement and grace which distinguished them from all other buildings of the period." In no single spot are more of these treasures of architectural craftsmanship to be found than at Salem, Massachusetts. Salem was a prosperous seaport. Her citizens from the early days of the eighteenth century amassed comfortable fortunes in the fisheries and the overseas trade, and they spent their money at home, building houses comparable in elegance and good taste with the best manor houses of Virginia. The doorways and interior woodwork particularly — the mantels, paneling, and stairways — exhibit a remarkable feeling for classic detail and a restraint and care in workmanship seldom found elsewhere. This interior woodwork was almost invariably made of white pine which grew in abundance along the New England coast, and which offered an excellent material for carving. It was nearly always well seasoned before its use and was kept protected by white paint; as a result it has resisted the effects of time to a remarkable extent. But the most noteworthy thing about it is the workmanship — the skill, ingenuity, and technical knowledge displayed in its application to specific needs. Unquestionably the skill which these carpenters acquired in wood carving and ornamental work generally was due largely to their training in the Salem shipyards, where fine carving and accurately fitted and proportioned work was always in demand. They learned their trade amid conditions calculated to develop it to its highest plane. Many of the details, in fact, strongly suggest marine cabin work. But beneath it all lay the true spirit of craftsman ship inherent in the Yankee artisan — the impulse to do things as well as they could be done. At first one is inclined to marvel at the knowledge of styles which these wood workers evidently possessed. Most of them were Yankees born and bred; they did not travel; they never saw the best examples of English Georgian work. But they were not illiterate men. They knew how to use books, and it was from books as well as from their masters that they doubtless drew a large share of their inspiration. The Salem period from 1785 to 1810 reflects strikingly the influence of Robert and James Adam, whose books on interior decoration appeared in 1783 and 1786. The Salem master carpenters had access to the best architectural books of the period, but they were not slavish copyists. They adapted the best that they found, and the style suffered not in its translation at their hands. The names of most of these artists in wood have been forgotten, but one stands out preëminent as master of them all — Samuel McIntire. It was he who impressed his personality most definitely on the architecture of Salem from 1782 to 1811. He designed nearly all of the best houses of that period. To him more than to any other is due the credit for our heritage of classic workmanship still to be seen in Salem. Samuel McIntire was born, lived, and died in Salem. He never went abroad, and so far as we know he learned all he knew from his books and from the ship builders and carpenters of his native town. All of his work was done in and near Salem. In

spite of these limitations of training, however, McIntire's work

displays a depth and breadth of artistic feeling and understanding

that are truly remarkable in view of his restricted opportunities. He

was the artistic descendant of Inigo Jones, Sir Christopher Wren,

Grinling Gibbons, and the brothers Adam; he was also their peer in

originality as well as in fidelity to the best classic traditions.

More chaste and severe than Wren and Gibbons, he was more fanciful

than Adam. Perhaps it was his very freedom from the schools that gave

him faith in his own genius to do the thing that best suited given

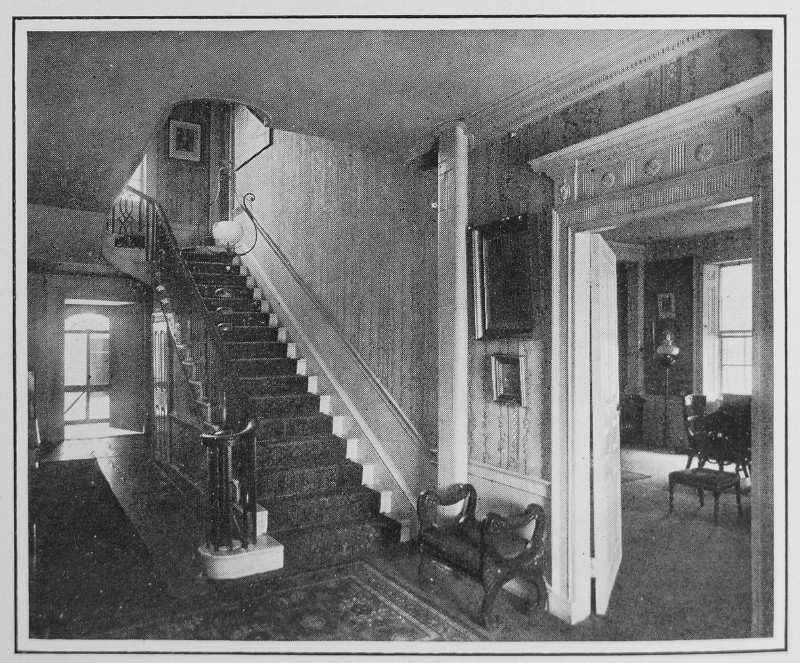

conditions, and this faith seldom led him astray. Hall in the Nichols House, Salem, designed by McIntire. The picture includes the original carved gate-posts as well as a bit of fine woodwork.

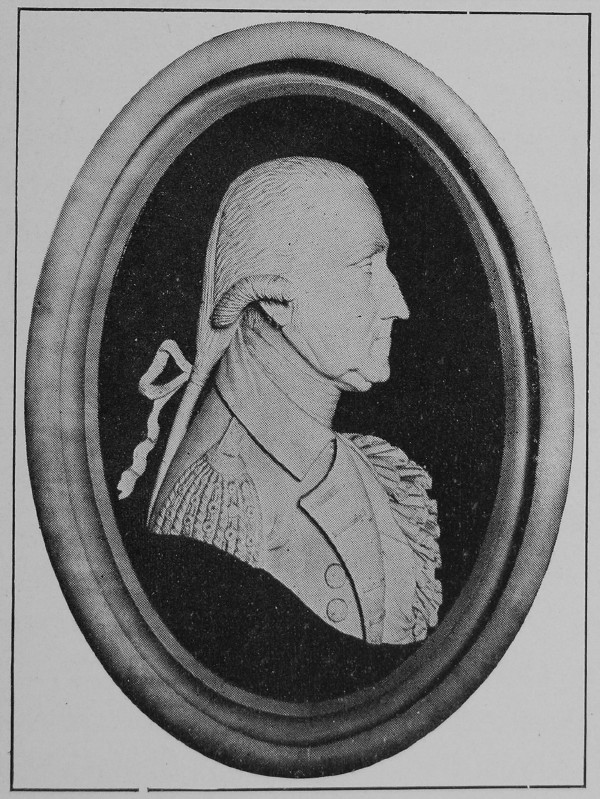

Few of the details of McIntire's life have been preserved in any form. The best sketch of him, though exasperatingly brief, is to be found in the diary of William Bentley, D.D., pastor of the East Church, Salem. On February 7, 1811, Bentley wrote as follows: "This day Salem was deprived of one of the most ingenious men it had in it. Samuel McIntire, aet. 54, in Summer Street. He was descended of a family of Carpenters who had no claims on public favor and was educated at a branch of that business. By attention he soon gained a superiority to all of his occupation and the present Court House, the North and South Meeting Houses, and indeed all the improvements of Salem for nearly thirty years past have been done under his eye. In Sculpture he had no rival in New England and I possess some specimens which I should not scruple to compare with any I ever saw. To the best of my abilities I encouraged him in this branch. In Music he had a good taste and tho' not presuming to be an original composer, he was among our best Judges and most able performers. All the instruments we use he could understand and was the best person to be employed in correcting any defects, or repairing them. He had a fine person, a majestic appearance, calm countenance, great self command and amiable temper. He was welcome but never intruded. He had complained of some obstruction in the chest, but when he died it was unexpectedly. The late increase of workmen in wood has been from the demand for exportation and this has added nothing to the character and reputation of the workmen, so that upon the death of Mr. McIntire no man is left to be consulted upon a new plan of execution beyond his bare practice." A brief obituary notice in the Salem Gazette of February 8, 1811, also shows the esteem in which McIntire was held: "Died:

Mr. McIntire, a man much beloved and sincerely lamented. He was

originally bred to the occupation of a housewright but his vigorous

mind soon passed the limits of his profession and aspired to the

interesting and admirable science of architecture in which he

advanced far beyond most of his countrymen. He made an assiduous

study of the great classical masters with whose works,

notwithstanding their rarity in this country, Mr. McIntire had a very

intimate acquaintance."

Samuel McIntire was born in Salem in 1757. His father was Joseph McIntire, a joiner, and it is likely that he learned his trade from him. He studied and practised wood carving under local masters and soon became noted for his skill. This craft he practised all his life, though the need for architects where architects were scarce led him into the designing of homes. In one sense he never became a great architect. His houses are mostly the square, three-story mansions of the period, that leave much to be desired in the way of grace and variety. His fame rests rather on the beauty of the embellishments of these houses — their doorways, window frames, cornices, gateposts, and their incomparable interior woodwork. As was not uncommon in those days, McIntire's name suffered many variations in spelling, but the one given here is supported by the best authority. He died February 6, 1811, and was laid to rest in the Charter Street Burial Ground, Salem. His grave-stone, which is still to be seen, reads as follows:

He left three children, all boys; one other died in infancy. McIntire died intestate, but his executors drew up an inventory of his effects which is on record in the Essex County Probate Office and which contains much of interest to the searcher after McIntire data. This inventory shows that he was not a rich man. His house and shop were valued at $3,000 and his personal property at $1,190, besides some $963 in notes. This property was left to his widow, Elizabeth McIntire. The most interesting items on this list are his carving tools, his books, and his music and musical instruments. He left "a large hand organ with ten barrels," "a double bass (musical instrument)," a violin and case, and a collection of books of music, including an edition of Handel's "Messiah." His small but well selected library indicates his taste and culture. Among his architectural works were Palladio's Architecture, Ware's Architecture, Architecture by Langley, another by Paine, Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, a book of sculptures, and two volumes of French architecture. The possession of the Palladio explains much. In his shop was found a complete equipment of carver's, joiner's, and draughting tools, including three hundred chisels and gouges and forty-six molding planes. This set of tools was famous at the time for its size and completeness. He also left eight of his Washington medallions and a number of finished ornaments, etc. In 1792 McIntire took part in the first public architectural competition held in this country. He submitted plans for the new national capitol at Washington, but apparently they lacked impressiveness, for they were rejected. The original drawings, however, which are preserved by the Maryland Historical Society, exhibit great refinement and dignity. There were a few public buildings in Massachusetts which were built from his plans. He was the architect for the old South Church in Salem, which was built in 1804 and destroyed by fire in 1903. It was famous for its graceful steeple. The steeple of the Park Street Church, Boston, has been attributed to him, but erroneously. The old Salem Court House, completed in 1786, was designed by McIntire, and also the Registry of Deeds, erected on Broad Street in 1807. A mantel taken from this latter building is now to be seen at the Essex Institute. He also designed the old Assembly Hall, at 138 Federal Street, which was built in 1782 and was converted into a private residence about 1795. The

greater portion of McIntire's work, however, is to be found in the

mansions of Salem and vicinity, which are unquestionably among the

chief architectural treasures of eastern Massachusetts to-day. A

score or more of them are attributed to him. Among those which bear

the marks of authenticity are the Pierce-Johonnot-Nichols house at 80

Federal Street, built in 1782; Hamilton Hall, on Chestnut Street,

built in 1808; the Crowninshield mansion on Derby Street, built in

1810; the Derby-Rogers-Maynes house on Essex Street; the

White-Pingree house at 128 Essex Street, built in 1810; the Tucker-

Rice house, 129 Essex Street, built in 1800 and partly dismantled in

1910; the Cook-Oliver house, 142 Federal Street, erected in 1804.;

the Kimball house at 14 Pickman Street; Oak Hill, the Rogers home at

Peabody, built in 1800; and a few others.

One of the most noteworthy of these is the Nichols house, a splendid relic of the day of commercial prosperity. The interior woodwork here has been studied by architects for a generation or more and represents McIntire's most painstaking craftsmanship. The splendid porches and gateways also bear witness to his skill as a designer. Perhaps the most famous is the Cook-Oliver house. Its history is linked with that of the old Derby house which was in its day the most sumptuous mansion in this section of the country. In 1799 Elias Hasket Derby, a successful and wealthy merchant, erected a house on what is now Market Square at a cost of $80,000. McIntire was the architect and, as expense was not considered, he placed therein some of the finest of all his interior woodwork and carving. The plans of this house are now in the possession of the Essex Institute. Derby did not live long to enjoy this house, and upon his death it was offered for sale, as his heirs found its maintenance beyond their means. No purchaser appeared, and the house was finally torn down in 1814 to make room for a public market. Meanwhile, Captain Samuel Cook had started building another McIntire house which was later occupied by his daughter, who, in 1825, married General Henry K. Oliver, mayor of Lawrence and Salem, and a man of progressive activities. This house was enriched with hand carving. When the Derby house was torn down its timbers and woodwork were purchased by Salem citizens, and Captain Cook secured some of the finest of the McIntire gate-posts, mantels, etc., for his new home, so that the Oliver house to-day contains some of the most noteworthy of McIntire's work. Fortunately for posterity the great Salem fire just missed this house. It was here that General Oliver composed his famous hymn, "Federal Street." A third house which contains a Wealth of McIntire's work is Oak Hill, at Peabody, near Salem. Its chimney pieces, door frames, cornices, etc., are remarkable for their fine and beautiful detail and exquisite proportions and represent the great carver and designer at his best. In 1802 the Salem

Common Was graded

and planted with trees and named Washington Square. In 1805, McIntire

designed and executed wooden gateways for the east and West sides of

the square — elaborate arches embellished with carvings. For

the

western gateway he carved a medallion likeness of General Washington,

thirty-eight by fifty-six inches in size. When the arches were taken

down in 1850 this medallion was removed to the Town Hall and is now

to be seen at the Essex Institute. It was carved in wood after

drawings from life made by McIntire during Washington's visit to

Salem in 1789.

McIntire undoubtedly attempted sculpture in a modest way, but few authentic examples of his work have been preserved. Perhaps the most interesting of these is a bust of Governor Winthrop, carved in wood in 1789 for William Bentley and now owned by the American Antiquarian Society. Any

attempt to analyze McIntire's style too closely, and to pick out

hall-marks for identification, is likely to lead one into deep water.

He had his favorite motifs and design details, but they differ but

slightly from those of other American craftsmen of the period who,

like McIntire, felt the Adam influence, and there were some who did

not scruple to copy him. But his workmanship so far surpassed that of

his rivals that a careful study of contemporary work makes it not

difficult to pick out the handicraft of the master. His proportions

were always perfect, his details fine, and his balance between plain

surfaces and decoration carefully studied. His finely modeled

cornices, pilasters, wainscot borders, and lintels are never

over-elaborate, never weak, and his applied ornament is always

clean-cut, graceful, and chaste. It would be difficult to discover,

in the Old World or the New, a more thoroughly satisfying expression

of the woodworker's art than the work of this master carpenter of

Salem. |