|

JACK AND THE BEAN-STALK

N the days of King

Alfred, there lived a poor woman, whose cottage was situated in a

remote

country village, a great many miles from London. She had been a widow

some

years, and had an only child named Jack, whom she indulged to a fault:

the

consequence of her blind partiality was, that Jack did not pay the

least attention

to any thing she said, but was indolent, careless, and extravagant. His

follies

were not owing to a bad disposition, but that his mother had never

checked him.

By degrees, she disposed of all she possessed — scarcely any thing

remained but

a cow. The poor woman one day met Jack with tears in her eyes; her

distress was

great, and for the first time in her life she could not help

reproaching him,

saying, ‘Oh! you wicked child, by your ungrateful course of life you

have at

last brought me to beggary and ruin. — Cruel, cruel boy! I have not

money

enough to purchase even a bit of bread for another day — nothing now

remains to

sell but my poor cow! I am sorry to part with her; it grieves me sadly,

but we

must not starve.’ For a few minutes, Jack felt a degree of remorse, but

it was

soon over, and he began teasing his mother to let him sell the cow at

the next

village, so much, that she at last consented. As he was going along, he

met a

butcher, who inquired why he was driving the cow from home? Jack

replied, he

was going to sell it. The butcher held some curious beans in his hat;

they were

of various colors, and attracted Jack’s attention; this did not pass

unnoticed

by the butcher, who, knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the

time to

take an advantage of it; and determined not to let slip so good an

opportunity,

asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all the

beans in

his hat for her. The silly boy could not conceal the pleasure he felt

at what

he supposed so great an offer, the bargain was struck instantly, and

the cow

exchanged for a few paltry beans. Jack made the best of his way home,

calling

aloud to his mother before he reached home, thinking to surprise her. N the days of King

Alfred, there lived a poor woman, whose cottage was situated in a

remote

country village, a great many miles from London. She had been a widow

some

years, and had an only child named Jack, whom she indulged to a fault:

the

consequence of her blind partiality was, that Jack did not pay the

least attention

to any thing she said, but was indolent, careless, and extravagant. His

follies

were not owing to a bad disposition, but that his mother had never

checked him.

By degrees, she disposed of all she possessed — scarcely any thing

remained but

a cow. The poor woman one day met Jack with tears in her eyes; her

distress was

great, and for the first time in her life she could not help

reproaching him,

saying, ‘Oh! you wicked child, by your ungrateful course of life you

have at

last brought me to beggary and ruin. — Cruel, cruel boy! I have not

money

enough to purchase even a bit of bread for another day — nothing now

remains to

sell but my poor cow! I am sorry to part with her; it grieves me sadly,

but we

must not starve.’ For a few minutes, Jack felt a degree of remorse, but

it was

soon over, and he began teasing his mother to let him sell the cow at

the next

village, so much, that she at last consented. As he was going along, he

met a

butcher, who inquired why he was driving the cow from home? Jack

replied, he

was going to sell it. The butcher held some curious beans in his hat;

they were

of various colors, and attracted Jack’s attention; this did not pass

unnoticed

by the butcher, who, knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the

time to

take an advantage of it; and determined not to let slip so good an

opportunity,

asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all the

beans in

his hat for her. The silly boy could not conceal the pleasure he felt

at what

he supposed so great an offer, the bargain was struck instantly, and

the cow

exchanged for a few paltry beans. Jack made the best of his way home,

calling

aloud to his mother before he reached home, thinking to surprise her.  When she saw the

beans, and heard Jack’s account, her patience quite forsook her: she

kicked the

beans away in a passion — they flew in all directions — some were

scattered in

the garden. Not having any thing to eat, they both went supperless to

bed. Jack

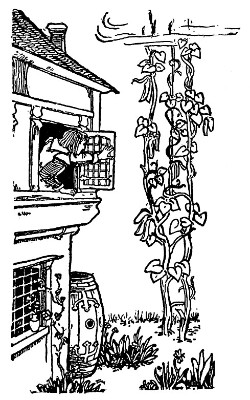

woke early in the morning, and seeing something uncommon from the

window of his

bed-chamber, ran down stairs into the garden, where he soon discovered

that

some of the beans had taken root, and sprung up surprisingly: the

stalks were

of an immense thickness, and had so entwined, that they formed a ladder

nearly

like a chain in appearance. Looking upward, he could not discern the

top, it

appeared to be lost in the clouds: he tried it, found it firm, and not

to be

shaken. He quickly formed the resolution of endeavouring to climb up to

the

top, in order to seek his fortune, and ran to communicate his intention

to his

mother, not doubting but she would be equally pleased with himself. She

declared he should not go; said it would break her heart if he did —

entreated,

and threatened — but all in vain. Jack set out, and after climbing for

some

hours, reached the top of the bean-stalk, fatigued and quite exhausted.

Looking

around, he found himself in a strange country; it appeared to be a

desert,

quite barren, not a tree, shrub, house, or living creature to be seen;

here and

there were scattered fragments of stone; and at unequal distances,

small heaps

of earth were loosely thrown together. When she saw the

beans, and heard Jack’s account, her patience quite forsook her: she

kicked the

beans away in a passion — they flew in all directions — some were

scattered in

the garden. Not having any thing to eat, they both went supperless to

bed. Jack

woke early in the morning, and seeing something uncommon from the

window of his

bed-chamber, ran down stairs into the garden, where he soon discovered

that

some of the beans had taken root, and sprung up surprisingly: the

stalks were

of an immense thickness, and had so entwined, that they formed a ladder

nearly

like a chain in appearance. Looking upward, he could not discern the

top, it

appeared to be lost in the clouds: he tried it, found it firm, and not

to be

shaken. He quickly formed the resolution of endeavouring to climb up to

the

top, in order to seek his fortune, and ran to communicate his intention

to his

mother, not doubting but she would be equally pleased with himself. She

declared he should not go; said it would break her heart if he did —

entreated,

and threatened — but all in vain. Jack set out, and after climbing for

some

hours, reached the top of the bean-stalk, fatigued and quite exhausted.

Looking

around, he found himself in a strange country; it appeared to be a

desert,

quite barren, not a tree, shrub, house, or living creature to be seen;

here and

there were scattered fragments of stone; and at unequal distances,

small heaps

of earth were loosely thrown together.

Jack seated himself

pensively upon a block of stone, and thought of his mother — he

reflected with

sorrow upon his disobedience in climbing the bean-stalk against her

will; and

concluded that he must die with hunger. However he walked on, hoping to

see a

house where he might beg something to eat and drink; presently a

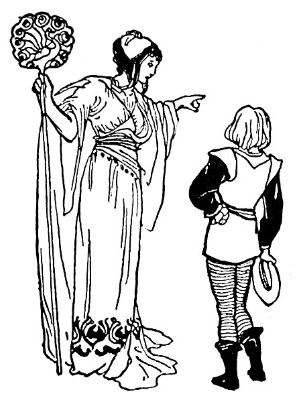

handsome young

woman appeared at a distance: as she approached, Jack could not help

admiring

how beautiful and lively she looked; she was dressed in the most

elegant

manner, and had a small white wand in her hand, on the top of which was

a

peacock of pure gold. While Jack was

looking with great surprise at this charming female, she came up to

him, and

with a smile of the most bewitching sweetness, inquired how he came

there. Jack

related the circumstance of the bean-stalk. She asked him if he

recollected his

father; he replied he did not; and added, there must be some mystery

relating

to him, because if he asked his mother who his father was, she always

burst

into tears, and appeared violently agitated, nor did she recover

herself for

some days after; one thing, however, he could not avoid observing upon

these

occasions, which was, that she always carefully avoided answering him,

and even

seemed afraid of speaking, as if there was some secret connected with

his

father’s history which she must not disclose. The young woman replied,

‘I will

reveal the whole story; your mother must not. But, before I begin, I

require a

solemn promise on your part to do what I command; I am a fairy, and if

you do

not perform exactly what I desire, you will be destroyed.’ Jack was

frightened

at her menaces, but promised to fulfil her injunctions exactly, and the

fairy

thus addressed him: Jack seated himself

pensively upon a block of stone, and thought of his mother — he

reflected with

sorrow upon his disobedience in climbing the bean-stalk against her

will; and

concluded that he must die with hunger. However he walked on, hoping to

see a

house where he might beg something to eat and drink; presently a

handsome young

woman appeared at a distance: as she approached, Jack could not help

admiring

how beautiful and lively she looked; she was dressed in the most

elegant

manner, and had a small white wand in her hand, on the top of which was

a

peacock of pure gold. While Jack was

looking with great surprise at this charming female, she came up to

him, and

with a smile of the most bewitching sweetness, inquired how he came

there. Jack

related the circumstance of the bean-stalk. She asked him if he

recollected his

father; he replied he did not; and added, there must be some mystery

relating

to him, because if he asked his mother who his father was, she always

burst

into tears, and appeared violently agitated, nor did she recover

herself for

some days after; one thing, however, he could not avoid observing upon

these

occasions, which was, that she always carefully avoided answering him,

and even

seemed afraid of speaking, as if there was some secret connected with

his

father’s history which she must not disclose. The young woman replied,

‘I will

reveal the whole story; your mother must not. But, before I begin, I

require a

solemn promise on your part to do what I command; I am a fairy, and if

you do

not perform exactly what I desire, you will be destroyed.’ Jack was

frightened

at her menaces, but promised to fulfil her injunctions exactly, and the

fairy

thus addressed him:

‘Your

father was a

rich man, his disposition remarkably benevolent: he was very good to

the poor,

and constantly relieving them: he made it a rule never to let a day

pass

without doing good to some person. On one particular day in the week,

he kept

open house, and invited only those who were reduced and had lived well.

He always

presided

himself, and did all in his power to render his guests comfortable; the

rich

and the great were not invited. The servants were all happy, and

greatly

attached to their master and mistress. Your father, though only a

private

gentleman, was as rich as a prince, and he deserved all he possessed,

for he

only lived to do good. Such a man was soon known and talked of. A giant

lived a

great many miles off: this man was altogether as wicked as your father

was

good; he was in his heart envious, covetous, and cruel; but he had the

art ‘of

concealing those vices. He was poor, and wished to enrich himself at

any rate.

Hearing your father spoken of, he formed the design of becoming

acquainted with

him, hoping to ingratiate himself into your father’s favour. He removed

quickly

into your neighbourhood, caused to be reported that he was a gentleman

who had

just lost all he possessed by an earthquake, and found it difficult to

escape

with his life; his wife was with him. Your father gave credit to his

story, and

pitied him; he gave him handsome apartments in his own house, and

caused him

and his wife to be treated like visitors of consequence, little

imagining that

the giant was meditating a horrid return for all his favours.

Things

went on in

this way for some time, the giant becoming daily more impatient to put

his plan

into execution; at last a favourable opportunity presented itself. Your

father’s house was at some distance from the seashore, but with a glass

the

coast could be seen distinctly. The giant was one day using the

telescope; the

wind was very high; he saw a fleet of ships in distress off the rock;

he

hastened to your father, mentioned the circumstance. and eagerly

requested he

would send all the servants he could spare to relieve the sufferers.

Every one

was instantly despatched, except the porter and your nurse; the giant

then

joined your father in the study, and appeared to be delighted — he

really was

so. Your father recommended a favourite book, and was handing it down:

the

giant took the opportunity, and stabbed him; he instantly fell down

dead. The

giant left the body, found the porter and nurse, and presently

despatched them;

being determined to have no living witnesses of his crimes. You were

then only

three months old; your mother had you in her arms in a remote part of

the

house, and was ignorant of what was going on; she went into the study,

but how

was she shocked, on discovering your father a corpse, and weltering in

his

blood! she was stupefied with horror and grief, and was motionless. The

giant,

who was seeking her, found her in that state, and hastened to serve her

and you

as he had done her husband, but she fell at his feet, and in a pathetic

manner

besought him to spare your life and hers.

‘Remorse,

for a

moment, seemed to touch the barbarian’s heart: he granted your lives;

but first

he made her take a most solemn oath, never to inform you who your

father was,

or to answer any questions concerning him: assuring her, that if she

did, he

would certainly discover her, and put both of you to death in the most

cruel

manner. Your mother took you in her arms, and fled as quickly as

possible; she

was scarcely gone when the giant repented that he had suffered her to

escape:

he would have pursued her instantly; but he had to provide for his own

safety;

as it was necessary he should be gone before the servants returned.

Having

gained your father’s confidence, he knew where to find all his

treasure: he

soon loaded himself and his wife, set the house on fire in several

places, and

when the servants returned, the house was burned quite down to the

ground. Your

poor mother, forlorn, abandoned, and forsaken, wandered with you a

great many

miles from this scene of desolation; fear added to her haste; she

settled in

the cottage where you were brought up, and it was entirely owing to her

fear of

the giant, that she never mentioned your father to you. I became your

father’s

guardian at his birth; but fairies have laws to which they are subject

as well

as mortals. A short time before the giant went to your father’s, I

transgressed; my punishment was a suspension of power for a limited

time — an

unfortunate circumstance, as it totally prevented my succouring your

father.

The day on

which

you met the butcher, as you went to sell your mother’s cow, my power

was

restored. It was I who secretly prompted you to take the beans in

exchange for

the cow. By my power, the bean-stalk grew to so great a height, and

formed a

ladder. I need not add that I inspired you with a strong desire to

ascend the

ladder. The giant lives in this country: you are the person appointed

to punish

him for all his wickedness. You will have dangers and difficulties to

encounter, but you must persevere in avenging the death of your father,

or you

will not prosper in any of your undertakings, but will always be

miserable. As

to the giant’s possessions, you may seize on all you can; for every

thing he

has is yours, though now you are unjustly deprived of it. One thing I

desire —

do not let your mother know you are acquainted with your father’s

history, till

you see me again. Go along the direct road, you will soon see the house

where

your cruel enemy lives. While you do as I order you, I will protect and

guard

you; but, remember, if you dare disobey my commands, a most dreadful

punishment

awaits you.’

When

the fairy had

concluded, she disappeared, leaving Jack to pursue his journey. He

walked on

till after sunset, when, to his great joy, he espied a large mansion.

This

agreeable sight revived his drooping spirits; he redoubled his speed,

and soon

reached it. A plain-looking woman was at the door — he accosted her,

begging

she would give him a morsel of bread and a night’s lodging. She

expressed the

greatest surprise at seeing him; and said it was quite uncommon to see

a human

being near their house, for it was well known that her husband was a

large and

very powerful giant, and that he would never eat any thing but human

flesh, if

he could possibly get it; that he did not think any thing of walking

fifty

miles to procure it, usually being out the whole day for that purpose. When

the fairy had

concluded, she disappeared, leaving Jack to pursue his journey. He

walked on

till after sunset, when, to his great joy, he espied a large mansion.

This

agreeable sight revived his drooping spirits; he redoubled his speed,

and soon

reached it. A plain-looking woman was at the door — he accosted her,

begging

she would give him a morsel of bread and a night’s lodging. She

expressed the

greatest surprise at seeing him; and said it was quite uncommon to see

a human

being near their house, for it was well known that her husband was a

large and

very powerful giant, and that he would never eat any thing but human

flesh, if

he could possibly get it; that he did not think any thing of walking

fifty

miles to procure it, usually being out the whole day for that purpose.

This

account

greatly terrified Jack, but still he hoped to elude the giant, and

therefore he

again entreated the woman to take him in for one night only, and hide

him where

she thought proper. The good woman at last suffered herself to be

persuaded,

for she was of a compassionate and generous disposition, and took him

into the

house. First, they entered a fine large hall, magnificently furnished;

they

then passed through several spacious rooms, all in the same style of

grandeur;

but they appeared to be quite forsaken and desolate. A long gallery was

next;

it was very dark — just light enough to show that, instead of

a wall on one

side, there was a grating of iron, which parted off a dismal dungeon,

from

whence issued the groans of those poor victims whom the cruel giant

reserved in

confinement for his own voracious appetite. Poor Jack was half dead

with fear,

and would have given the world to have been with his mother again, for appeared to be quite forsaken and desolate. A long gallery was

next;

it was very dark — just light enough to show that, instead of

a wall on one

side, there was a grating of iron, which parted off a dismal dungeon,

from

whence issued the groans of those poor victims whom the cruel giant

reserved in

confinement for his own voracious appetite. Poor Jack was half dead

with fear,

and would have given the world to have been with his mother again, for

he now

began to fear that he should never see her more, and gave himself up

for lost;

he even mistrusted the good woman, and thought she had let him into the

house

for no other purpose than to lock him up among the unfortunate people

in the

dungeon. At the farther end of the gallery there was a spacious

kitchen, and a

very excellent fire was burning in the grate. The good woman bid Jack

sit down,

and gave him plenty to eat and drink. Jack, not seeing any thing here

to make

him uncomfortable, soon forgot his fear, and was just beginning to

enjoy

himself, when he was aroused by a loud knocking at the street-door,

which made

the whole house shake: the giant’s wife ran to secure him in

the oven, and then

went to let her husband in. Jack heard him accost her in a voice like

thunder,

saying: ‘Wife, I smell fresh meat.’ —

‘Oh! my dear,’ replied she, ‘it is

nothing but the people in the dungeon.’ The giant appeared to

believe her, and

walked into the very kitchen where poor Jack was concealed, who shook,

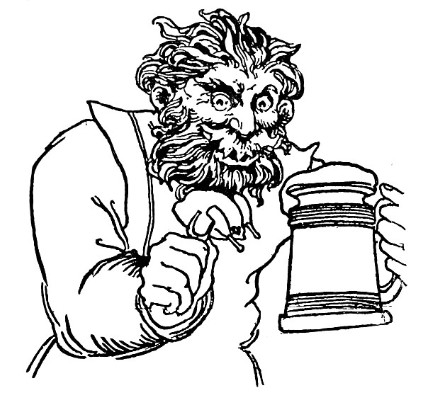

trembled, and was more terrified than he had yet been. At last, the

monster

seated himself quietly by the fireside, whilst his wife prepared

supper. By

degrees Jack recovered himself sufficiently to look at the giant

through a

small crevice: he was quite astonished to see what an amazing quantity

he

devoured, and thought he never would have done eating and drinking.

When supper

was ended, the giant desired his wife to bring him his hen. A very

beautiful

hen was then brought, and placed on the table before him.

Jack’s curiosity was

very great to see what would happen: he observed that every time the

giant said

‘Lay!’ the hen laid an egg of solid gold. The giant

amused himself a long time

with his hen; meanwhile his wife went to bed. At length the giant fell

asleep

by the fire-side, and snored like the roaring of a cannon. At daybreak,

Jack,

finding the giant still asleep, and not likely to awaken soon, crept

softly out

of his hiding-place, seized the hen, and ran off with her. He met with

some

difficulty in finding his way out of the house, but at last he reached

the road

with safety: he easily found the way to the bean-stalk, and descended

it better

and quicker than he expected. His mother was overjoyed to see him; he

found her

crying bitterly, and lamenting his hard fate, for she concluded he had

come to

some shocking end through his rashness. Jack was impatient to show his

hen, and

inform his mother how valuable it was. ‘And now,

mother,’ said Jack, ‘I have

brought home that which will quickly make us rich; and I hope to make

you some

amends for the affliction I have caused you through my idleness,

extravagance,

and folly.’ The hen produced as many golden eggs as they

desired: they sold

them, and in a little time became possessed of as much riches as they

wanted.

For some months Jack and his mother lived very happily together; but he

being

very desirous of travelling, recollecting the fairy’s

commands, and fearing

that if he delayed, she would put her threats into execution, longed to

climb

the bean-stalk, and pay the giant another visit, in order to carry away

some

more of his treasures; for, during the time that Jack was in the

giant’s

mansion, whilst he lay concealed in the oven, he learned from the

conversation

that took place between the giant and his wife, that he possessed some

wonderful curiosities. Jack thought of his journey again and again, but

still

he could not summon resolution enough to break it to his mother, being

well

assured that she would endeavour to prevent his going. However, one day

he told

her boldly that he must take a journey up the bean-stalk; she begged

and prayed

him not to think of it, and tried all in her power to dissuade him: she

told

him that the giant’s wife would certainly know him again, and

that the giant

would desire nothing better than to get him into his power, that he

might put

him to a cruel death, in order to be revenged for the loss of his hen.

Jack,

finding that all his arguments were useless, pretended to give up the

point, though

resolved to go at all events. He had a dress prepared which would

disguise him,

and something to colour his skin: he thought it impossible for any one

to

recollect him in this dress. he now

began to fear that he should never see her more, and gave himself up

for lost;

he even mistrusted the good woman, and thought she had let him into the

house

for no other purpose than to lock him up among the unfortunate people

in the

dungeon. At the farther end of the gallery there was a spacious

kitchen, and a

very excellent fire was burning in the grate. The good woman bid Jack

sit down,

and gave him plenty to eat and drink. Jack, not seeing any thing here

to make

him uncomfortable, soon forgot his fear, and was just beginning to

enjoy

himself, when he was aroused by a loud knocking at the street-door,

which made

the whole house shake: the giant’s wife ran to secure him in

the oven, and then

went to let her husband in. Jack heard him accost her in a voice like

thunder,

saying: ‘Wife, I smell fresh meat.’ —

‘Oh! my dear,’ replied she, ‘it is

nothing but the people in the dungeon.’ The giant appeared to

believe her, and

walked into the very kitchen where poor Jack was concealed, who shook,

trembled, and was more terrified than he had yet been. At last, the

monster

seated himself quietly by the fireside, whilst his wife prepared

supper. By

degrees Jack recovered himself sufficiently to look at the giant

through a

small crevice: he was quite astonished to see what an amazing quantity

he

devoured, and thought he never would have done eating and drinking.

When supper

was ended, the giant desired his wife to bring him his hen. A very

beautiful

hen was then brought, and placed on the table before him.

Jack’s curiosity was

very great to see what would happen: he observed that every time the

giant said

‘Lay!’ the hen laid an egg of solid gold. The giant

amused himself a long time

with his hen; meanwhile his wife went to bed. At length the giant fell

asleep

by the fire-side, and snored like the roaring of a cannon. At daybreak,

Jack,

finding the giant still asleep, and not likely to awaken soon, crept

softly out

of his hiding-place, seized the hen, and ran off with her. He met with

some

difficulty in finding his way out of the house, but at last he reached

the road

with safety: he easily found the way to the bean-stalk, and descended

it better

and quicker than he expected. His mother was overjoyed to see him; he

found her

crying bitterly, and lamenting his hard fate, for she concluded he had

come to

some shocking end through his rashness. Jack was impatient to show his

hen, and

inform his mother how valuable it was. ‘And now,

mother,’ said Jack, ‘I have

brought home that which will quickly make us rich; and I hope to make

you some

amends for the affliction I have caused you through my idleness,

extravagance,

and folly.’ The hen produced as many golden eggs as they

desired: they sold

them, and in a little time became possessed of as much riches as they

wanted.

For some months Jack and his mother lived very happily together; but he

being

very desirous of travelling, recollecting the fairy’s

commands, and fearing

that if he delayed, she would put her threats into execution, longed to

climb

the bean-stalk, and pay the giant another visit, in order to carry away

some

more of his treasures; for, during the time that Jack was in the

giant’s

mansion, whilst he lay concealed in the oven, he learned from the

conversation

that took place between the giant and his wife, that he possessed some

wonderful curiosities. Jack thought of his journey again and again, but

still

he could not summon resolution enough to break it to his mother, being

well

assured that she would endeavour to prevent his going. However, one day

he told

her boldly that he must take a journey up the bean-stalk; she begged

and prayed

him not to think of it, and tried all in her power to dissuade him: she

told

him that the giant’s wife would certainly know him again, and

that the giant

would desire nothing better than to get him into his power, that he

might put

him to a cruel death, in order to be revenged for the loss of his hen.

Jack,

finding that all his arguments were useless, pretended to give up the

point, though

resolved to go at all events. He had a dress prepared which would

disguise him,

and something to colour his skin: he thought it impossible for any one

to

recollect him in this dress.

In a few

mornings

after this, he arose very early, changed his complexion, and,

unperceived by

any one, climbed the bean-stalk a second time. He was greatly fatigued

when he

reached the top, and very hungry. Having rested some time on one of the

stones,

he pursued his journey to the giant’s mansion. He reached it late in

the

evening: the woman was at the door as before. Jack addressed her, at

the same

time telling her a pitiful tale, and requesting that she would give him

some

victuals and drink, and also a night’s lodging.

She told

him (what

he knew before very well) about her husband being a powerful and cruel

giant;

and also that she one night admitted a poor, hungry, friendless boy,

who was

half dead with travelling; that the little ungrateful fellow had stolen

one of

the giant’s treasures; and, ever since that, her husband had been worse

than

before, used her very cruelly, and continually upbraided her with being

the

cause of his misfortune. Jack was at no loss to discover that he was

attending

to the account of a story in which he was the principal actor: he did

his best

to persuade the good woman to admit him, but found it a very hard task.

At last

she consented; and as she led the way, Jack observed that every thing

was just

as he had found it before: she took him into the kitchen, and after he

had done

eating and drinking, she hid him in an old lumber-closet. The giant

returned at

the usual time, and walked in so heavily, that the house was shaken to

its

foundation. He seated himself by the fire, and soon after exclaimed:

‘Wife! I

smell fresh meat!’ The wife replied, it was the crows, who had brought

a piece

of raw meat, and left it on the top of the house. Whilst supper was

preparing,

the giant was very ill-tempered and impatient, frequently lifting up

his hand

to strike his wife, for not being quick enough; she, however, was

always so

fortunate as to elude the blow. He was also continually upbraiding her

with the

loss of his wonderful hen. The giant at last having ended his voracious

supper,

and eaten till he was quite satisfied, said to his wife: ‘I must have

something

to amuse me; either my bags of money or my harp.’ After a great deal of

ill-humour, and having teased his wife some time, he commanded her to

bring

down his bags of gold and silver. Jack, as before, peeped out of his

hiding-place, and presently his wife brought two bags into the room:

they were

of a very large size; one was filled with new guineas, and the other

with new

shillings. They were both placed before the giant, who began

reprimanding his

poor wife most severely for staying so long; she replied, trembling

with fear,

that they were so heavy, that she could scarcely lift them; and

concluded, at

last, that she would never again bring them down stairs; adding, that

she had

nearly fainted, owing to their weight. This so exasperated the giant,

that he raised

his hand to strike her; she, however, escaped, and went to bed, leaving

him to

count over his treasure, by way of amusement. The giant took his bags,

and

after turning them over and over, to see that they were in the same

state as he

left them, began to count their contents. First, the bag which

contained the

silver was emptied, and the contents placed upon the table. Jack viewed

the

glittering heaps with delight, and most heartily wished them in his own

possession. The giant (little thinking he was so narrowly watched)

reckoned the

silver over several times; and then, having satisfied himself that all

was

safe, put it into the bag again, which he made very secure. The other

bag was

opened next, and the guineas placed upon the table. If Jack was pleased

at the

sight of the silver, how much more delighted he felt when he saw such a

heap of

glittering gold! He even had the boldness to think of gaining both

bags; but

suddenly recollecting himself, he began to fear that the giant would

sham

sleep, the better to entrap any one who might be concealed. When the

giant had

counted over the gold till he was tired, he put it up, if possible,

more secure

than he had put up the silver before; he then fell back on his chair by

the

fireside, and fell asleep. He snored so loud, that Jack compared his

noise to

the roaring of the sea in a high wind, when the tide is coming in. At

last,

Jack concluded him to be asleep, and therefore secure, stole out of his

hiding-place, and approached the giant, in order to carry off the two

bags of

money; but just as he laid his hand upon one of the bags, a little dog,

whom he

had not perceived before, started from under the giant’s chair, and

barked at

Jack most furiously, who now gave himself up for lost: fear riveted him

to the

spot. Instead of endeavouring to escape, he stood still, though

expecting his

enemy to awake every instant.  Contrary, however, to

his expectation, the giant

continued in a sound sleep, and the dog grew weary of barking. Jack now

began

to recollect himself, and on looking round, saw a large piece of meat;

this he

threw to the dog, who instantly seized it, and took it into the

lumber-closet,

which Jack had just left. Finding himself delivered from a noisy and

troublesome enemy, and seeing the Contrary, however, to

his expectation, the giant

continued in a sound sleep, and the dog grew weary of barking. Jack now

began

to recollect himself, and on looking round, saw a large piece of meat;

this he

threw to the dog, who instantly seized it, and took it into the

lumber-closet,

which Jack had just left. Finding himself delivered from a noisy and

troublesome enemy, and seeing the giant did not awake, Jack boldly seized the

bags, and throwing them over his shoulders, ran out of the kitchen. He

reached

the street door in safety, and found it quite daylight. In his way to

the top

of the bean-stalk, he found himself greatly incommoded with the weight

of the

money bags; and really they were so heavy that he could scarcely carry

them.

Jack was overjoyed when he found himself near the bean-stalk; he soon

reached

the bottom, and immediately ran to seek his mother; to his great

surprise, the

cottage was deserted; he ran from one room to another, without being

able to

find anyone; he then hastened into the village, hoping to see some of

the

neighbours, who could inform him where he could find his mother. An old

woman

at last directed him to a neighbouring house, where she was ill of a

fever. He

was greatly shocked on finding her apparently dying, and could scarcely

bear

his own reflections, on knowing himself to be the cause. On being

informed of

our hero’s safe return, his mother, by degrees, revived, and gradually

recovered. Jack presented her with his two valuable bags: they lived

happily

and comfortably; the cottage was rebuilt, and well furnished. giant did not awake, Jack boldly seized the

bags, and throwing them over his shoulders, ran out of the kitchen. He

reached

the street door in safety, and found it quite daylight. In his way to

the top

of the bean-stalk, he found himself greatly incommoded with the weight

of the

money bags; and really they were so heavy that he could scarcely carry

them.

Jack was overjoyed when he found himself near the bean-stalk; he soon

reached

the bottom, and immediately ran to seek his mother; to his great

surprise, the

cottage was deserted; he ran from one room to another, without being

able to

find anyone; he then hastened into the village, hoping to see some of

the

neighbours, who could inform him where he could find his mother. An old

woman

at last directed him to a neighbouring house, where she was ill of a

fever. He

was greatly shocked on finding her apparently dying, and could scarcely

bear

his own reflections, on knowing himself to be the cause. On being

informed of

our hero’s safe return, his mother, by degrees, revived, and gradually

recovered. Jack presented her with his two valuable bags: they lived

happily

and comfortably; the cottage was rebuilt, and well furnished.

For three

years

Jack heard no more of the bean-stalk, but he could not forget it;

though he

feared making his mother unhappy: she would not mention the hated

bean-stalk,

lest it should remind him of taking another journey. Notwithstanding

the

comforts Jack enjoyed at home, his mind dwelt continually upon the

beanstalk;

for the fairy’s menaces, in case of his disobedience, were ever present

to his

mind, and prevented him from being happy; he could think of nothing

else. It

was in vain endeavouring to amuse himself; he became thoughtful, and

would

arise at the first dawn of day, and view the bean-stalk for hours

together. His

mother saw that something preyed heavily upon his mind, and endeavoured

to

discover the cause; but Jack knew too well what the consequence would

be,

should she succeed. He did his utmost, therefore, to conquer the great

desire

he had for another journey up the beanstalk. Finding, however, that his

inclination grew too powerful for him, he began to make secret

preparations for

his journey, and, on the longest day, arose as soon as it was light,

ascended

the bean-stalk, and reached the top with some little trouble. He found

the

road, journey, etc., much as it was on the two former times; he arrived

at the

giant’s mansion in the evening, and found his wife standing, as usual,

at the

door. Jack had disguised himself so completely, that she did not appear

to have

the least recollection of him; however, when he pleaded hunger and

poverty, in

order to gain admittance, he found it very difficult to persuade her.

At last

he prevailed, and was concealed in the copper. When the giant returned,

he

said, ‘I smell fresh meat!’ But Jack felt quite composed, as he had

said so

before, and had been soon satisfied: however, the giant started up

suddenly,

and, notwithstanding all his wife could say, he searched all round the

room. For three

years

Jack heard no more of the bean-stalk, but he could not forget it;

though he

feared making his mother unhappy: she would not mention the hated

bean-stalk,

lest it should remind him of taking another journey. Notwithstanding

the

comforts Jack enjoyed at home, his mind dwelt continually upon the

beanstalk;

for the fairy’s menaces, in case of his disobedience, were ever present

to his

mind, and prevented him from being happy; he could think of nothing

else. It

was in vain endeavouring to amuse himself; he became thoughtful, and

would

arise at the first dawn of day, and view the bean-stalk for hours

together. His

mother saw that something preyed heavily upon his mind, and endeavoured

to

discover the cause; but Jack knew too well what the consequence would

be,

should she succeed. He did his utmost, therefore, to conquer the great

desire

he had for another journey up the beanstalk. Finding, however, that his

inclination grew too powerful for him, he began to make secret

preparations for

his journey, and, on the longest day, arose as soon as it was light,

ascended

the bean-stalk, and reached the top with some little trouble. He found

the

road, journey, etc., much as it was on the two former times; he arrived

at the

giant’s mansion in the evening, and found his wife standing, as usual,

at the

door. Jack had disguised himself so completely, that she did not appear

to have

the least recollection of him; however, when he pleaded hunger and

poverty, in

order to gain admittance, he found it very difficult to persuade her.

At last

he prevailed, and was concealed in the copper. When the giant returned,

he

said, ‘I smell fresh meat!’ But Jack felt quite composed, as he had

said so

before, and had been soon satisfied: however, the giant started up

suddenly,

and, notwithstanding all his wife could say, he searched all round the

room.

Whilst this

was

going forward, Jack was exceedingly terrified, and ready to die with

fear,

wishing himself at home a thousand times; but when the giant approached

the

copper, and put his hand upon the lid, Jack thought his death was

certain. The

giant ended his search there, without moving the lid, and seated

himself

quietly by the fireside. This fright nearly overcame poor Jack; he was

afraid

of moving or even breathing, lest he should be discovered. The giant at

last

ate a hearty supper: when he had finished, he commanded his wife to

fetch down his

harp. Jack peeped under the copper-lid, and soon saw the most beautiful

harp

that could be imagined: it was placed by the giant on the table, who

said,

‘Play!’ and it instantly played of its own accord, without being

touched. The

music was uncommonly fine. Jack was delighted, and felt more anxious to

get the

harp into his possession, than either of the former treasures. The

giant’s soul

was not attuned to harmony, and the music soon lulled him into a sound

sleep.

Now, therefore, was the time to carry off the harp, as the giant

appeared to be

in a more profound sleep than usual. Jack soon determined, got out of

the

copper, and seized the harp. The harp was enchanted by a fairy: it

called out

loudly — ‘Master! master!’ The giant awoke, stood up, and tried to

pursue Jack;

but he had drank so much, that he could hardly stand. Poor Jack ran as

fast as

he could: in a little time the giant recovered sufficiently to walk

slowly, or

rather, to reel after him: had he been sober, he must have overtaken

Jack

instantly; but, as he then was, Jack contrived to be first at the top

of the

bean-stalk. The giant called after him in a voice like thunder, and

sometimes

was very near him. The moment Jack got down the bean-stalk he called

out for a

hatchet; one was brought him directly; just at that instant, the giant

was

beginning to descend; but Jack, with his hatchet, cut the bean-stalk

close off

at the root, which made the giant fall headlong into the garden: the

fall

killed him, thereby releasing the world from a barbarous enemy. Jack’s

mother

was delighted when she saw the beanstalk destroyed. At this instant the

fairy

appeared: she first addressed Jack’s mother and explained every

circumstance

relating to the journeys up the bean-stalk. The fairy charged Jack to

be

dutiful to his mother, and to follow his father’s good example, which

was the

only way to be happy. She then disappeared. Jack heartily begged his

mother’s

pardon for all the sorrow and affliction he had caused her, promising

most

faithfully to be very dutiful and obedient to her for the future. Whilst this

was

going forward, Jack was exceedingly terrified, and ready to die with

fear,

wishing himself at home a thousand times; but when the giant approached

the

copper, and put his hand upon the lid, Jack thought his death was

certain. The

giant ended his search there, without moving the lid, and seated

himself

quietly by the fireside. This fright nearly overcame poor Jack; he was

afraid

of moving or even breathing, lest he should be discovered. The giant at

last

ate a hearty supper: when he had finished, he commanded his wife to

fetch down his

harp. Jack peeped under the copper-lid, and soon saw the most beautiful

harp

that could be imagined: it was placed by the giant on the table, who

said,

‘Play!’ and it instantly played of its own accord, without being

touched. The

music was uncommonly fine. Jack was delighted, and felt more anxious to

get the

harp into his possession, than either of the former treasures. The

giant’s soul

was not attuned to harmony, and the music soon lulled him into a sound

sleep.

Now, therefore, was the time to carry off the harp, as the giant

appeared to be

in a more profound sleep than usual. Jack soon determined, got out of

the

copper, and seized the harp. The harp was enchanted by a fairy: it

called out

loudly — ‘Master! master!’ The giant awoke, stood up, and tried to

pursue Jack;

but he had drank so much, that he could hardly stand. Poor Jack ran as

fast as

he could: in a little time the giant recovered sufficiently to walk

slowly, or

rather, to reel after him: had he been sober, he must have overtaken

Jack

instantly; but, as he then was, Jack contrived to be first at the top

of the

bean-stalk. The giant called after him in a voice like thunder, and

sometimes

was very near him. The moment Jack got down the bean-stalk he called

out for a

hatchet; one was brought him directly; just at that instant, the giant

was

beginning to descend; but Jack, with his hatchet, cut the bean-stalk

close off

at the root, which made the giant fall headlong into the garden: the

fall

killed him, thereby releasing the world from a barbarous enemy. Jack’s

mother

was delighted when she saw the beanstalk destroyed. At this instant the

fairy

appeared: she first addressed Jack’s mother and explained every

circumstance

relating to the journeys up the bean-stalk. The fairy charged Jack to

be

dutiful to his mother, and to follow his father’s good example, which

was the

only way to be happy. She then disappeared. Jack heartily begged his

mother’s

pardon for all the sorrow and affliction he had caused her, promising

most

faithfully to be very dutiful and obedient to her for the future.

|

N the days of King

Alfred, there lived a poor woman, whose cottage was situated in a

remote

country village, a great many miles from London. She had been a widow

some

years, and had an only child named Jack, whom she indulged to a fault:

the

consequence of her blind partiality was, that Jack did not pay the

least attention

to any thing she said, but was indolent, careless, and extravagant. His

follies

were not owing to a bad disposition, but that his mother had never

checked him.

By degrees, she disposed of all she possessed — scarcely any thing

remained but

a cow. The poor woman one day met Jack with tears in her eyes; her

distress was

great, and for the first time in her life she could not help

reproaching him,

saying, ‘Oh! you wicked child, by your ungrateful course of life you

have at

last brought me to beggary and ruin. — Cruel, cruel boy! I have not

money

enough to purchase even a bit of bread for another day — nothing now

remains to

sell but my poor cow! I am sorry to part with her; it grieves me sadly,

but we

must not starve.’ For a few minutes, Jack felt a degree of remorse, but

it was

soon over, and he began teasing his mother to let him sell the cow at

the next

village, so much, that she at last consented. As he was going along, he

met a

butcher, who inquired why he was driving the cow from home? Jack

replied, he

was going to sell it. The butcher held some curious beans in his hat;

they were

of various colors, and attracted Jack’s attention; this did not pass

unnoticed

by the butcher, who, knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the

time to

take an advantage of it; and determined not to let slip so good an

opportunity,

asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all the

beans in

his hat for her. The silly boy could not conceal the pleasure he felt

at what

he supposed so great an offer, the bargain was struck instantly, and

the cow

exchanged for a few paltry beans. Jack made the best of his way home,

calling

aloud to his mother before he reached home, thinking to surprise her.

N the days of King

Alfred, there lived a poor woman, whose cottage was situated in a

remote

country village, a great many miles from London. She had been a widow

some

years, and had an only child named Jack, whom she indulged to a fault:

the

consequence of her blind partiality was, that Jack did not pay the

least attention

to any thing she said, but was indolent, careless, and extravagant. His

follies

were not owing to a bad disposition, but that his mother had never

checked him.

By degrees, she disposed of all she possessed — scarcely any thing

remained but

a cow. The poor woman one day met Jack with tears in her eyes; her

distress was

great, and for the first time in her life she could not help

reproaching him,

saying, ‘Oh! you wicked child, by your ungrateful course of life you

have at

last brought me to beggary and ruin. — Cruel, cruel boy! I have not

money

enough to purchase even a bit of bread for another day — nothing now

remains to

sell but my poor cow! I am sorry to part with her; it grieves me sadly,

but we

must not starve.’ For a few minutes, Jack felt a degree of remorse, but

it was

soon over, and he began teasing his mother to let him sell the cow at

the next

village, so much, that she at last consented. As he was going along, he

met a

butcher, who inquired why he was driving the cow from home? Jack

replied, he

was going to sell it. The butcher held some curious beans in his hat;

they were

of various colors, and attracted Jack’s attention; this did not pass

unnoticed

by the butcher, who, knowing Jack’s easy temper, thought now was the

time to

take an advantage of it; and determined not to let slip so good an

opportunity,

asked what was the price of the cow, offering at the same time all the

beans in

his hat for her. The silly boy could not conceal the pleasure he felt

at what

he supposed so great an offer, the bargain was struck instantly, and

the cow

exchanged for a few paltry beans. Jack made the best of his way home,

calling

aloud to his mother before he reached home, thinking to surprise her.  For three

years

Jack heard no more of the bean-stalk, but he could not forget it;

though he

feared making his mother unhappy: she would not mention the hated

bean-stalk,

lest it should remind him of taking another journey. Notwithstanding

the

comforts Jack enjoyed at home, his mind dwelt continually upon the

beanstalk;

for the fairy’s menaces, in case of his disobedience, were ever present

to his

mind, and prevented him from being happy; he could think of nothing

else. It

was in vain endeavouring to amuse himself; he became thoughtful, and

would

arise at the first dawn of day, and view the bean-stalk for hours

together. His

mother saw that something preyed heavily upon his mind, and endeavoured

to

discover the cause; but Jack knew too well what the consequence would

be,

should she succeed. He did his utmost, therefore, to conquer the great

desire

he had for another journey up the beanstalk. Finding, however, that his

inclination grew too powerful for him, he began to make secret

preparations for

his journey, and, on the longest day, arose as soon as it was light,

ascended

the bean-stalk, and reached the top with some little trouble. He found

the

road, journey, etc., much as it was on the two former times; he arrived

at the

giant’s mansion in the evening, and found his wife standing, as usual,

at the

door. Jack had disguised himself so completely, that she did not appear

to have

the least recollection of him; however, when he pleaded hunger and

poverty, in

order to gain admittance, he found it very difficult to persuade her.

At last

he prevailed, and was concealed in the copper. When the giant returned,

he

said, ‘I smell fresh meat!’ But Jack felt quite composed, as he had

said so

before, and had been soon satisfied: however, the giant started up

suddenly,

and, notwithstanding all his wife could say, he searched all round the

room.

For three

years

Jack heard no more of the bean-stalk, but he could not forget it;

though he

feared making his mother unhappy: she would not mention the hated

bean-stalk,

lest it should remind him of taking another journey. Notwithstanding

the

comforts Jack enjoyed at home, his mind dwelt continually upon the

beanstalk;

for the fairy’s menaces, in case of his disobedience, were ever present

to his

mind, and prevented him from being happy; he could think of nothing

else. It

was in vain endeavouring to amuse himself; he became thoughtful, and

would

arise at the first dawn of day, and view the bean-stalk for hours

together. His

mother saw that something preyed heavily upon his mind, and endeavoured

to

discover the cause; but Jack knew too well what the consequence would

be,

should she succeed. He did his utmost, therefore, to conquer the great

desire

he had for another journey up the beanstalk. Finding, however, that his

inclination grew too powerful for him, he began to make secret

preparations for

his journey, and, on the longest day, arose as soon as it was light,

ascended

the bean-stalk, and reached the top with some little trouble. He found

the

road, journey, etc., much as it was on the two former times; he arrived

at the

giant’s mansion in the evening, and found his wife standing, as usual,

at the

door. Jack had disguised himself so completely, that she did not appear

to have

the least recollection of him; however, when he pleaded hunger and

poverty, in

order to gain admittance, he found it very difficult to persuade her.

At last

he prevailed, and was concealed in the copper. When the giant returned,

he

said, ‘I smell fresh meat!’ But Jack felt quite composed, as he had

said so

before, and had been soon satisfied: however, the giant started up

suddenly,

and, notwithstanding all his wife could say, he searched all round the

room.  Whilst this

was

going forward, Jack was exceedingly terrified, and ready to die with

fear,

wishing himself at home a thousand times; but when the giant approached

the

copper, and put his hand upon the lid, Jack thought his death was

certain. The

giant ended his search there, without moving the lid, and seated

himself

quietly by the fireside. This fright nearly overcame poor Jack; he was

afraid

of moving or even breathing, lest he should be discovered. The giant at

last

ate a hearty supper: when he had finished, he commanded his wife to

fetch down his

harp. Jack peeped under the copper-lid, and soon saw the most beautiful

harp

that could be imagined: it was placed by the giant on the table, who

said,

‘Play!’ and it instantly played of its own accord, without being

touched. The

music was uncommonly fine. Jack was delighted, and felt more anxious to

get the

harp into his possession, than either of the former treasures. The

giant’s soul

was not attuned to harmony, and the music soon lulled him into a sound

sleep.

Now, therefore, was the time to carry off the harp, as the giant

appeared to be

in a more profound sleep than usual. Jack soon determined, got out of

the

copper, and seized the harp. The harp was enchanted by a fairy: it

called out

loudly — ‘Master! master!’ The giant awoke, stood up, and tried to

pursue Jack;

but he had drank so much, that he could hardly stand. Poor Jack ran as

fast as

he could: in a little time the giant recovered sufficiently to walk

slowly, or

rather, to reel after him: had he been sober, he must have overtaken

Jack

instantly; but, as he then was, Jack contrived to be first at the top

of the

bean-stalk. The giant called after him in a voice like thunder, and

sometimes

was very near him. The moment Jack got down the bean-stalk he called

out for a

hatchet; one was brought him directly; just at that instant, the giant

was

beginning to descend; but Jack, with his hatchet, cut the bean-stalk

close off

at the root, which made the giant fall headlong into the garden: the

fall

killed him, thereby releasing the world from a barbarous enemy. Jack’s

mother

was delighted when she saw the beanstalk destroyed. At this instant the

fairy

appeared: she first addressed Jack’s mother and explained every

circumstance

relating to the journeys up the bean-stalk. The fairy charged Jack to

be

dutiful to his mother, and to follow his father’s good example, which

was the

only way to be happy. She then disappeared. Jack heartily begged his

mother’s

pardon for all the sorrow and affliction he had caused her, promising

most

faithfully to be very dutiful and obedient to her for the future.

Whilst this

was

going forward, Jack was exceedingly terrified, and ready to die with

fear,

wishing himself at home a thousand times; but when the giant approached

the

copper, and put his hand upon the lid, Jack thought his death was

certain. The

giant ended his search there, without moving the lid, and seated

himself

quietly by the fireside. This fright nearly overcame poor Jack; he was

afraid

of moving or even breathing, lest he should be discovered. The giant at

last

ate a hearty supper: when he had finished, he commanded his wife to

fetch down his

harp. Jack peeped under the copper-lid, and soon saw the most beautiful

harp

that could be imagined: it was placed by the giant on the table, who

said,

‘Play!’ and it instantly played of its own accord, without being

touched. The

music was uncommonly fine. Jack was delighted, and felt more anxious to

get the

harp into his possession, than either of the former treasures. The

giant’s soul

was not attuned to harmony, and the music soon lulled him into a sound

sleep.

Now, therefore, was the time to carry off the harp, as the giant

appeared to be

in a more profound sleep than usual. Jack soon determined, got out of

the

copper, and seized the harp. The harp was enchanted by a fairy: it

called out

loudly — ‘Master! master!’ The giant awoke, stood up, and tried to

pursue Jack;

but he had drank so much, that he could hardly stand. Poor Jack ran as

fast as

he could: in a little time the giant recovered sufficiently to walk

slowly, or

rather, to reel after him: had he been sober, he must have overtaken

Jack

instantly; but, as he then was, Jack contrived to be first at the top

of the

bean-stalk. The giant called after him in a voice like thunder, and

sometimes

was very near him. The moment Jack got down the bean-stalk he called

out for a

hatchet; one was brought him directly; just at that instant, the giant

was

beginning to descend; but Jack, with his hatchet, cut the bean-stalk

close off

at the root, which made the giant fall headlong into the garden: the

fall

killed him, thereby releasing the world from a barbarous enemy. Jack’s

mother

was delighted when she saw the beanstalk destroyed. At this instant the

fairy

appeared: she first addressed Jack’s mother and explained every

circumstance

relating to the journeys up the bean-stalk. The fairy charged Jack to

be

dutiful to his mother, and to follow his father’s good example, which

was the

only way to be happy. She then disappeared. Jack heartily begged his

mother’s

pardon for all the sorrow and affliction he had caused her, promising

most

faithfully to be very dutiful and obedient to her for the future.